The social mobility gap between black and white Americans has barely narrowed in the last decades, and sharp differences in access to opportunity persist. This racial opportunity gap can, in part, be traced back to the neighborhoods where whites and blacks grow up: research from urban sociologists like Patrick Sharkey and Robert Sampson shows the damaging effects racial segregation and concentrated neighborhood poverty can have on children’s life chances. Washington D.C. is a case in point.

Stubborn Segregation in D.C:

Racial segregation has been declining over the last 50 years within the largest metropolitan areas, according to a 2012 study by The Manhattan Institute. But there are exceptions to this rule; one of those is the nation’s capital. In the District of Columbia (the central city, as opposed to the Washington metropolitan area) there remains a stark, persistent, white-black racial divide.

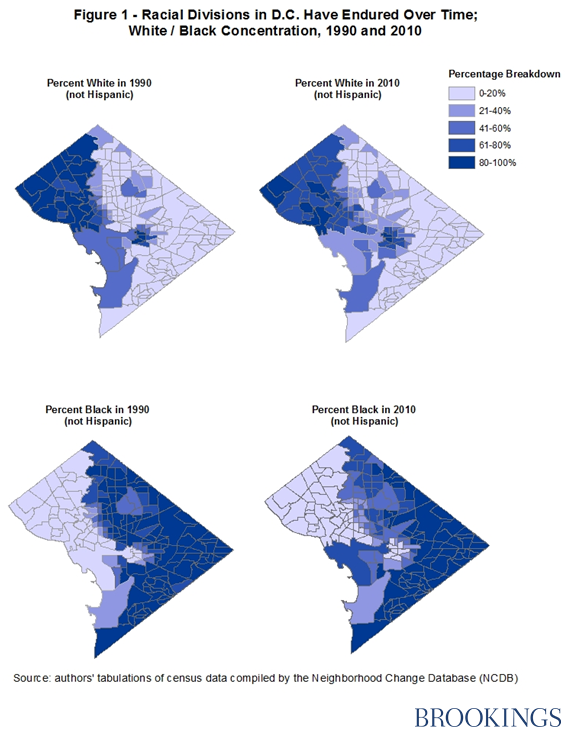

Figure 1 shows the percentage of white and black population in D.C. neighborhoods in 1990 and in 2010. A clear East-West racial divide can be seen:

Almost of all the census tracts that were “majority” white or black (i.e. over 60 percent of the population) in 1990 remained that way in 2010.

Segregation and opportunity

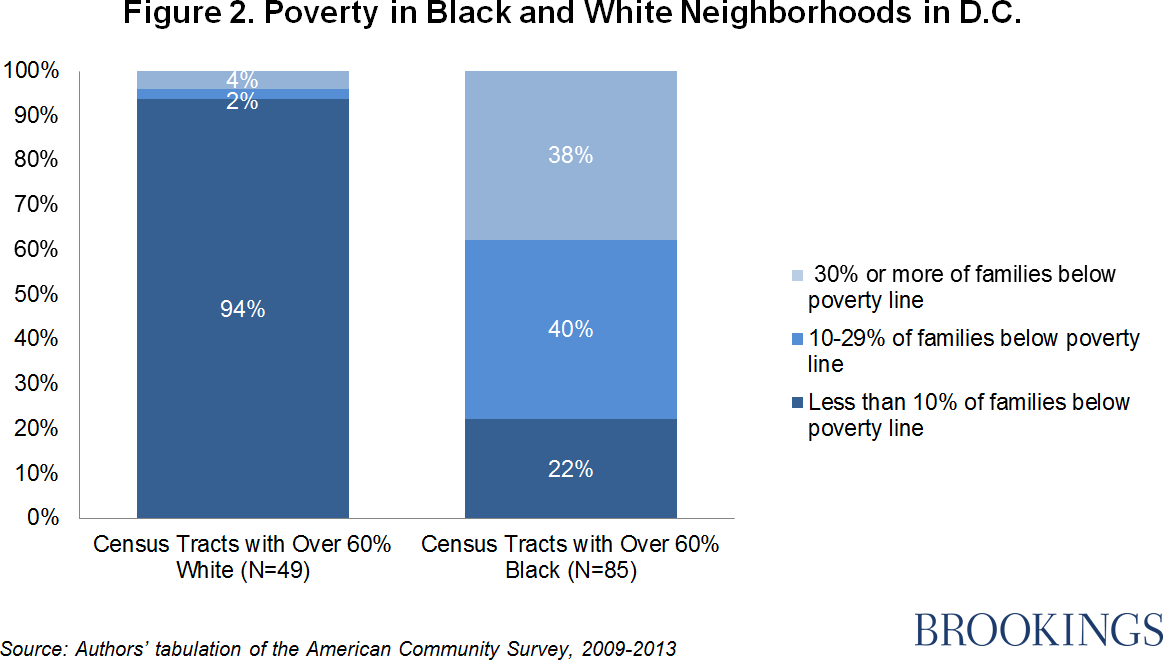

Racial segregation in central cities typically means greater concentrated poverty and fewer opportunities for economic mobility. As Figure 2 shows, 94 percent of the D.C. neighborhoods with a majority white population have less than 10 percent of their families living below the poverty line, compared with 22 percent of majority black neighborhoods. Meanwhile, just 4 percent of predominantly white neighborhoods have 30 percent or more of their families living below the poverty line, compared with 38 percent of predominantly black neighborhoods:

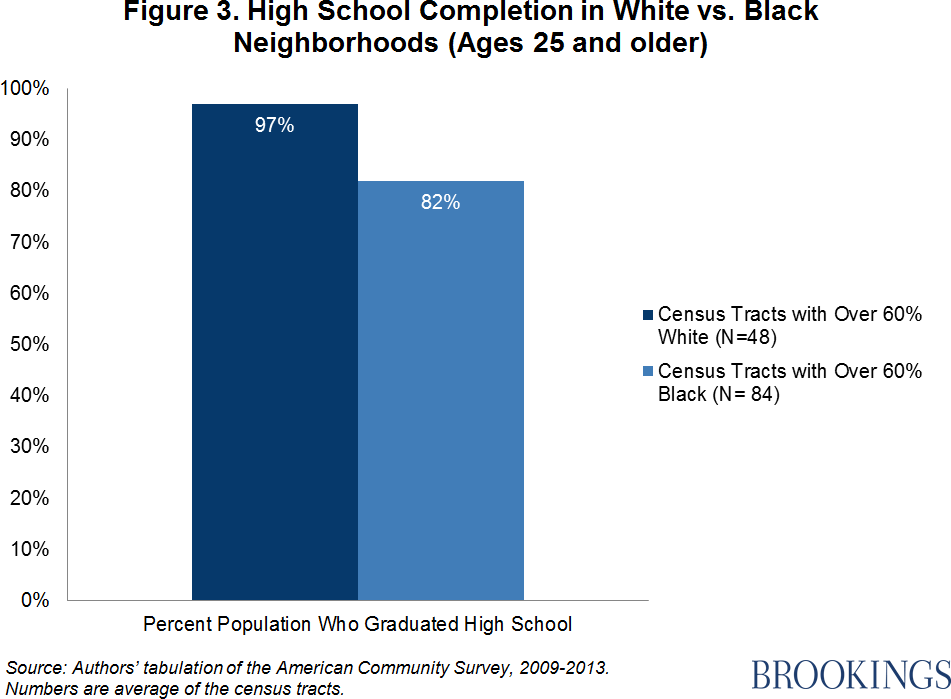

Black D.C. neighborhoods also have less-educated residents. As Figure 3 shows, 97% of people aged 25 and over in white neighborhoods have graduated high school, compared with only 82% in black neighborhoods:

Racial segregation, poverty and economic mobility

D.C’s continuing racial segregation is a warning sign, suggesting diverging destinies for whites and blacks in the city. A recent report by Richard Florida and Charlotta Mellander, of University of Toronto’s Martin Prosperity Institute, finds that, in more than 350 metropolitan areas across the United States, “all three types of segregation—income, educational, and occupational—are associated with one another.” Similarly, the Equality of Opportunity Project, developed by Harvard’s Raj Chetty and colleagues, finds a strong negative correlation between racial and income segregation and relative economic mobility.

Segregation is bad news on a number of fronts, including the negative implications for gaps in opportunity, and one of the starkest examples of the problem stares the nation’s legislators in the face.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Segregation and concentrated poverty in the nation’s capital

March 24, 2015