The good news: College attendance and graduation rates in the United States are on the rise. The bad news: class divides in postsecondary education are also widening.

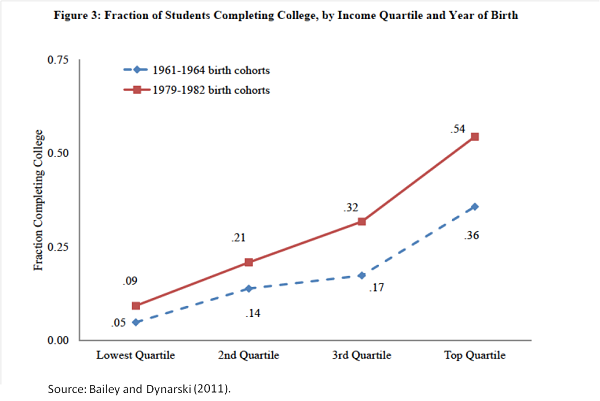

As Martha Bailey and I document in a recent paper, roughly 5 percent of people born to the lowest income quartile in the early 1960s earned a bachelor’s degree. That figure rose slightly, to 9 percent, among poor kids born in the early 1980s. By contrast, college completion rates for rich children (i.e., those born into the top income quartile) increased by 18 percentage points between the two cohorts. As a result, in less than twenty years, the income gap in college completion increased by almost 50 percent (from 31 to 45 percentage points).

Socioeconomic gaps emerge early on in the college pipeline. Rich kids are nearly three times more likely as poor kids to pursue postsecondary education. The news doesn’t get any better when we focus on the progression of students through college. Rich-poor gaps in college persistence and graduation have grown over the past decades. Less than a third of college enrollees from low-income families finish with a degree, half the rate of their better-off peers.

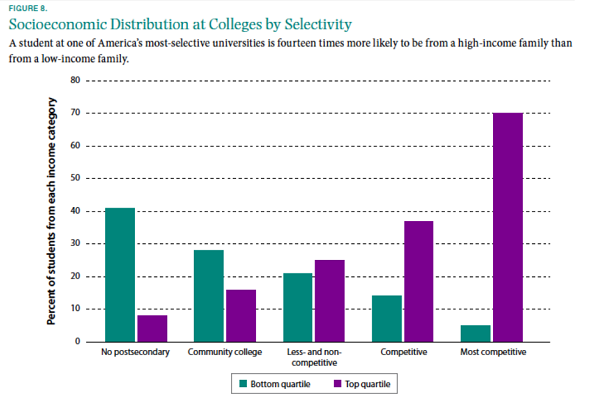

Part of the explanation for the lower completion rates of low-income students is that they go to lower- quality institutions. In a recent paper, Michael Bastedo and Ozan Jaquette find that a student at one of America’s most-selective universities is 14 times more likely to be from a high-income family than from a low-income family.

Source:

the Hamilton Project

There are number of factors driving these diverging trends, but part of the problem is that there just aren’t enough good colleges out there for low-income students. The number of high-quality institutions has remained roughly constant over time, despite the growth in college attendance. Funding for community colleges – the first stop for most low-income college-bound students – has not grown as quickly as enrollments, leading to overburdened counselors, long waitlists for classes, and delayed graduation. As a result, many low-income students have turned to for-profit colleges, where they are more likely to get deeply in debt. Tackling these supply-side constraints would be one important step towards closing the widening rich-poor gaps in postsecondary education.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Rising Inequality in Postsecondary Education

February 13, 2014