On December 6, Venezuelans head to the polls for legislative elections. They do so amidst a dramatic economic and social crisis: the annual inflation rate has reached 170 percent and the economy is expected to contract 10 percent in 2015, following a 4 percent contraction in 2014. Poverty rates are climbing rapidly, reaching levels that have not been seen since former President Hugo Chávez took office in 1999. The price of oil, the source of 95 percent of all foreign exchange earnings in Venezuela, has dropped more than 65 percent in two years. Venezuela’s international reserves have consequently reached historic lows of $14 billion, which is a critical level for a country that imports two-thirds of its consumer products. In the face of these difficulties, the Nicolás Maduro administration appears paralyzed, headed over the cliff towards financial ruin but unwilling to take corrective action.

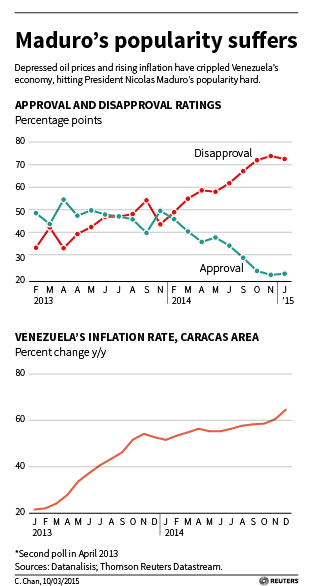

Approval ratings for Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro have plummeted in recent years, while the country’s inflation rate has spiked. Photo credit: Reuters.

A tilted playing field

Venezuela’s legislative elections would not normally attract much international attention. This time however, the Chavista movement, dominant since Chávez’s 1999 election, may lose control of the national legislature. The massive difference in the poll numbers, with the opposition running 20 to 30 points ahead of the government in the generic ballot running across all major national polls, suggests the government is headed for defeat. This has created high expectations among many Venezuelans that these elections will bring change, but there are still reasons to moderate expectations.

[T]he Chavista movement may lose control of the national legislature.

The Venezuelan system for apportioning legislative seats, a complex mix of proportional representation and single and multi-member districts, has been gerrymandered to favor the governing party. Despite that structural advantage, the present polls so favor the opposition that the results are difficult to predict. Indeed, it would be nearly impossible for the opposition to lose free and fair elections given the present polling numbers.

The government has reason to fear the accountability that might come from losing control of the legislature, including massive corruption and evidence of connections at the highest levels to international drug trafficking. The government has therefore done all it can to tilt the playing field in its favor. In a recent letter to Venezuela’s national electoral authority, Organization of American States Secretary General Luis Almagro spent 19 pages enumerating the many ways in which the government had manipulated electoral conditions: by disqualifying some political opponents from office and jailing others, by ensuring that almost all media is controlled by the state or by private businesses sympathetic to Chavismo, by using state resources to support government candidates, by imposing a state of emergency in key border states (mostly sympathetic to the opposition), and even by manipulating the design of the ballot to make it difficult for voters to find opposition candidates. Most troubling is the violence targeted at opposition rallies, including the assassination of an opposition leader in the state of Guárico on November 25.

The gulf between expectations and outcomes

All of these factors create a risk that the opposition will significantly underperform its poll numbers. In a highly polarized country where 63 percent of citizens have little or no confidence in the electoral authorities, a large gap between the expectations created by public opinion polls and the actual number of seats the opposition wins would likely be interpreted as fraud.

There is also a gap between popular expectations of what opposition control of the legislature would achieve and the powers available to this body. Legislatures in Latin America are weak relative to the executive branch, and Venezuela suffers from this syndrome particularly acutely. A simple majority of seats in the legislature would allow the opposition to pass laws, but it is only if the opposition were to reach a three-fifths majority in the legislature that they have the power to censure and remove government ministers or appoint new electoral authorities. And achieving this number of seats would be a heavy (although not impossible) lift for opposition parties to achieve in the elections.

The government has many ways to limit the powers of legislators. President Maduro could use a lame-duck session of the legislature (while his party still controls the majority) to pass an enabling law allowing him to rule by decree for the rest of his term. The governing party has also packed the Venezuelan Tribunal Supremo (Supreme Court) by demanding the resignation of sitting justices this fall and appointing new ones to fresh terms while the government still controls the legislature. This would allow the government to declare unconstitutional any inconvenient laws passed by an opposition-controlled legislature.

Hoping for the best, preparing for the worst

President Maduro has been adamant about rejecting the presence of international electoral observers during the December 6 elections. Since 2006, the Venezuelan government has seen electoral observers as too intrusive, particularly OAS missions whose reputation for professionalism may make the Maduro administration nervous. They have instead invited an electoral “accompaniment” mission from the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), but on terms that limit the ability of mission members to do their jobs. The mission’s credibility is further called into question because it is co-financed by the Venezuelan government. In the absence of a credible international mission, there will only be domestic electoral observers, who are particularly vulnerable to pressure from the government, to provide a second opinion on the vote’s integrity.

In the absence of trusted mechanisms for validating electoral results, the potential for a disputed outcome is worrisome. Under such circumstances, the mixture of heightened expectations, polarization, and low trust in the electoral authorities creates a risk of protests leading to state repression and violence. That risk is compounded by statements by President Maduro and his allies that raise questions about the government’s willingness to respect unfavorable electoral results, and that call on supporters to defend the revolution in the streets after December 6. In Venezuela, doubts over election results would make it even more difficult to find common ground to address the very serious economic and security problems facing the country.

Venezuela’s neighbors are not well-positioned to respond to a crisis. The Dilma Rousseff administration in Brazil, ideologically predisposed to sympathize with Maduro anyway, is mired in domestic corruption scandals and an economic recession. Colombia’s leaders are focused on peace negotiations with the FARC insurgency and are unwilling to rock the boat by addressing a crisis in Venezuela.

[E]lectoral fraud has been known to backfire on authoritarian leaders.

However, questionable results on December 6 may damage Venezuela’s reputation enough to provide political cover for other presidents in the region to push the Maduro administration to abide by the democratic principles in Venezuela’s constitution. Newly-elected Argentine President Mauricio Macri has already called for the Mercosur Democracy clause to be applied to Venezuela (a member state of this customs union). Venezuela’s increasing authoritarianism has also been widely criticized by civil society and legislative bodies in the region (most recently by 157 legislators from six countries in the hemisphere). And as some observers have pointed out, elections have catalyzing effects, and electoral fraud has been known to backfire on authoritarian leaders.

If the election falls significantly short of democratic standards, Venezuelans themselves will have to take the lead in defending electoral results at home. But together with pressure from their growing number of supporters among legislators, former presidents, judges, members of civil society, and the private sector in the Americas, they may well encourage some (and shame others) of the region’s presidents into living up to their countries’ international obligation to defend democracy in the Americas. And the United States, which has frequently stood alone when it has criticized the shortcomings of Venezuela’s present regime, will find that it has more allies than it expects in support of a democratic outcome to the December 6 elections.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Venezuelan elections: Could Chavismo lose?

December 2, 2015