Today’s employment report provided hopeful signals that momentum is continuing to develop in the labor market. The unemployment rate continued to edge down and expansions in employer payrolls continued to grow. Although still too high, the unemployment rate ticked down from 8.5 percent to 8.3 percent in January. Employer payrolls increased by 243,000 jobs in January—and an average of 201,000 jobs over the last three months—with the private sector again leading the way with 257,000 additional jobs.

In past months, The Hamilton Project has examined long-term trends in earnings for men and women, and the consequences of these trends for families and children. This month we continue to explore the relationship between economic trends and American families.

Fewer Americans are married today than at any point in at least 50 years. The causes of this trend and the consequences for Americans’ well-being are naturally the subject of much debate. Charles Murray’s new book, Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010, argues that the decline in marriage, and the concurrent decline in work, is the product of changes in values or social norms that have eroded both industriousness and marital values.

This argument ignores well-documented changes in demand that have caused the earnings of many Americans to decline. The decline in marriage is concentrated among these very same Americans. A large body of evidence links the decline in employment and earnings for less-skilled workers to globalization, technological change, and changes in labor market institutions—changes beyond the ability of individuals to control no matter what their values are.

One of the most important reasons we care about marriage is because of the clear association between marriage and poverty: women and children in single-parent households are at particular risk for living in poverty and indeed family earnings for half of the nation’s children have been falling over time. Rather than focusing on changing values, a more effective approach to addressing both poverty and marriage may be to improve economic opportunities for all Americans, particularly for low-skilled, less-educated workers.

As we explore the consequences of the changing economy, we also continue to explore the “jobs gap,” or the number of jobs that the U.S. economy needs to create in order to return to pre-recession employment levels while also absorbing the 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month.

The Link between Income and Marriage

Contrary to much of the hype around the decline in marriage, there are positive outcomes worth noting. In particular, many Americans are waiting longer to get married due to opportunities for women to pursue careers outside the home, due to better control over the timing of childbearing, and due to the ability to be more selective when choosing a spouse. These marriages starting later in life appear more stable and are less likely to end in divorce—a better outcome from any perspective. Delayed marriage contributes, in part, to the decline in the number of people married at a given time (see Stevenson and Wolfers 2007). However, it is also likely that the combination of declines in marriage and declines in economic opportunity have contributed to worse outcomes for some people, and especially for some children.

Social scientists have long posited a relationship between economic opportunity and marriage. William Julius Wilson, in The Truly Disadvantaged, argued that the decline in marriage and rise in single parenthood among urban blacks was directly a consequence of the declining economic fortunes of young black men. High rates of unemployment and incarceration meant that the local dating pool was populated by unmarriageable men—and the result was that women chose to live independently.

This story resonates broadly today because adverse changes in labor markets have recently impacted many Americans: for instance, in the last forty years, low- and middle-income men—those who experienced the biggest falls in real earnings over time—also experienced the sharpest decline in their chance of being married.

Incomes, Marriage Rates and Men

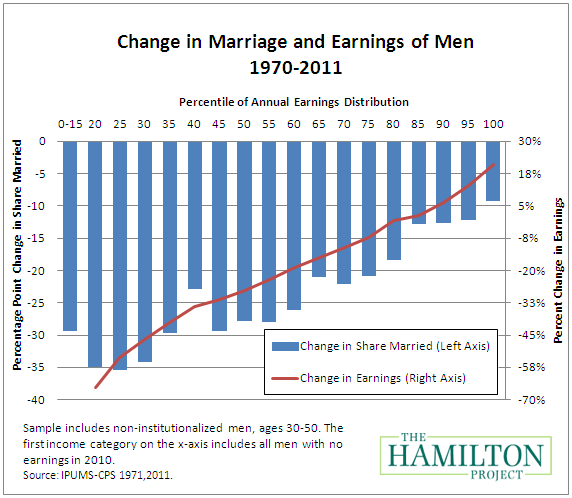

In the 1970s, the vast majority of middle-aged men were married, regardless of where they fell in the distribution of income. While marriage rates have declined across the board, the decline is far more pronounced among middle- and lower-income groups. The figure below shows both the change in earnings and the change in the share of men married by earnings percentile. The figure illustrates a strong correlation between changes in earnings and changes in marriage: men that experienced the most adverse economic changes also experienced the largest declines in marriage.

For men ages 30-50 in the top 10 percent of annual earnings—a group that saw real earnings increases over time—83 percent are married today, down modestly from about 95 percent in 1970. For the median male worker (who experienced a decline in earnings of roughly 28 percent), only 64 percent are married today, down from 91 percent 40 years ago. And at the bottom 25th percentile of earnings, where earnings have fallen by 60 percent, half of men are married, compared with 86 percent in 1970. While the share of men who have been divorced has increased across the earnings distribution, an increase in the share of men who have never been married is the largest contributor to lower marriage rates.

Incomes, Marriage Rates and Women

In contrast to men, American women have experienced large labor market gains during the past four decades. As women have gained more economic control over their lives, they have been offered more choices than they had just a few decades ago. Opportunities in the workplace have allowed women to become more financially independent, making marriage less of an economic necessity.

In 1970, 44 percent of women ages 30-50 had no independent earnings, compared to 25 percent of women today. Additionally, at the same time as more women have entered the labor force, women have also commanded higher wages. The median wage for female workers ages 30-50 has risen from roughly $19,000 in 1970 to $30,000 in 2010. If we combine rising employment and rising wages for female workers, we see large increases in wage across the earnings distribution.

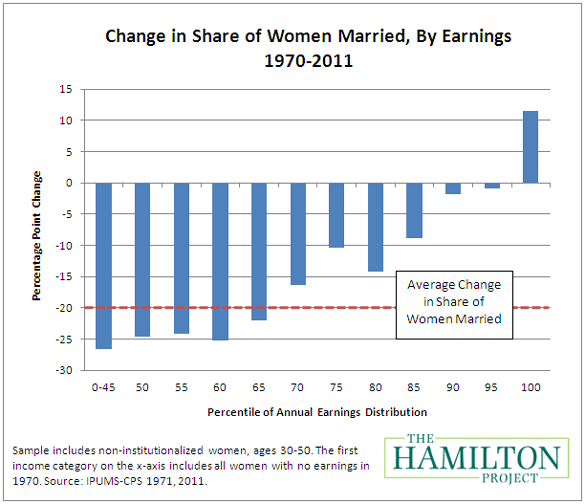

The growing economic opportunities for women have been accompanied by changes in marriage rates. Figure 2 underscores that, just as with men, the decline in marriage rates is not spread evenly across income levels. Marriage rates either held constant or increased for the top 10 percent of female earners over the last four decades. In contrast, the bottom 70 percent of female earners saw their marriage rates decline by more than 15 percentage points. Changing labor force participation complicates the calculation of changes in earning by earnings percentile for women, but the large increase in labor force participation rates makes a simple illustration of how these marital patterns correlate with changes in income—almost half of women had no independent earnings forty years ago.

Economic forces are likely to be important factors in these patterns. For women at the lower end of the economic spectrum, gains in the workplace have provided greater opportunities for independence. On the other hand, the shift away from families in which men enter the workforce and women work at home would have a smaller impact on high-income women, who now may choose to marry for other reasons (see Isen and Stevenson 2010; Goldin 1997).

It is important to understand what these changes mean for American families. One area of focus for policy makers is the rise in single-parent households and the consequences for America’s children. Indeed, rising income inequality is driven in part by changes in family composition: children born into single-parent families are relatively poorer than those born to married couples—particularly those who are college-educated and those with dual incomes. In a previous Hamilton Project analysis, we showed that over the last 40 years, family earnings have declined for half of all American children—an alarming trend for our nation’s future.

The January Jobs Gap

As of January, our nation continues to face a “jobs gap” of 11.7 million. Employment changes from this month as well as revisions to employment numbers by the Bureau of Labor Statistics reduced the measured jobs gap by about 390,000. These revisions reflect a stronger labor market than previous estimates predicted.

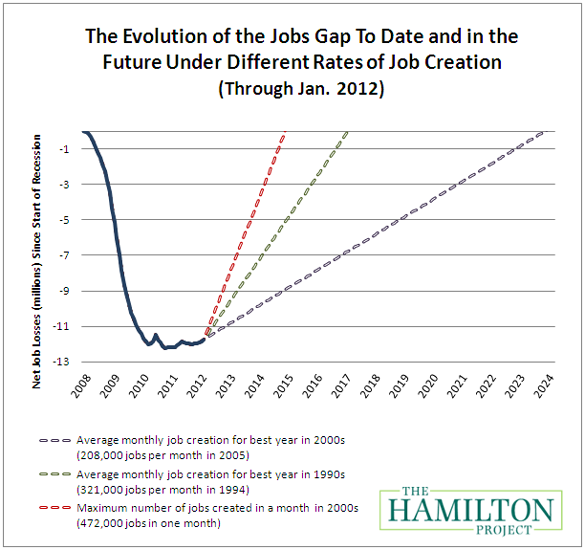

The chart below shows how the jobs gap has evolved since the start of the Great Recession in December 2007, and how long it will take to close under different assumptions for job growth. The solid line shows the net number of jobs lost since the Great Recession began. The broken lines track how long it will take to close the jobs gap under alternative assumptions about the rate of job creation going forward.

If the economy adds about 208,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 2000s, then it will take until November 2023—11 years and 9 months—to close the jobs gap. Given a more optimistic rate of 321,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 1990s, the economy will reach pre-recession employment levels by January 2017—not for another five years.

Conclusions

As workers face an extended economic slowdown, the U.S. may also confront related challenges on other fronts. Many factors have contributed to the changing relationship between income and marriage. The patterns that have emerged have important economic and social implications for the well-being of individuals and families. Most notably, parental income inequality among children has dramatically increased over the last thirty-five years, creating an uneven playing field for future generations.

There is no silver bullet for closing the marriage gap, but perhaps the most promising approach to improving family outcomes is to focus on the underlying economic contributors to the sea change in marriage and family structure. Investments in education and training would help put Americans back to work in well-paying jobs, promoting economic security that can lead to more and better marriages—and better opportunities for the children of those marriages. In today’s global economy, the competition for employment has become fierce and we must act to prepare American workers for the jobs of the future. A strong economy is a sound foundation for a strong social fabric.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Marriage Gap: The Impact of Economic and Technological Change on Marriage Rates

February 3, 2012