In my blog yesterday, “Don’t mind the construction, Turkey’s growing cities are good for development,” I argued that Turkey’s cities have been engines of economic growth. But despite the large economic gains Turkey’s urbanization has brought, it raises many questions. The huge investment in real estate has led some to worry that Turkey is experiencing a housing bubble. The eternal traffic jams in Istanbul make others complain that Turkey’s urban expansion has gone too far. The bland housing estates that adorn almost all Anatolian cities raise concerns that they may turn into Turkey’s version of France’s infamous housing estates. And of course, in 2013, the planned redevelopment of a green area in central Istanbul, the now infamous Gezi Park, triggered wide-spread street protests two years ago.

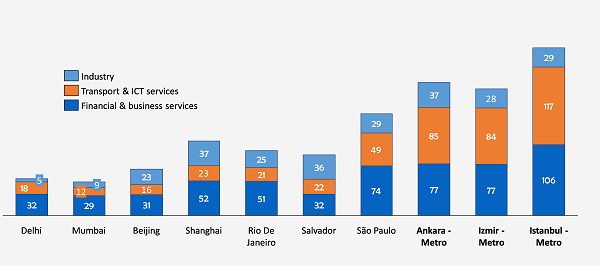

The Turkey Urbanization Review provides some evidence to allay these concerns. It shows, for instance, that while Turkish housing supply has increased dramatically, it is still outstripped by the increase in demand, particularly among lower-income households. Strong increases in demand to some extent mitigate concerns of overinvestment, though better data is clearly needed to know whether Turkey is at risk of a housing bubble. The Urbanization Review also shows that Istanbul and Izmir have seen their shares in Turkey’s overall urban population decline, as manufacturing activity moves to less congested areas. Turkey’s most advanced cities are increasingly becoming service hubs, producing specialized and diverse products for a global market, whereas Turkey’s inland cities take on easier, less specialized tasks. Thanks to specialization, productivity levels in Turkey’s richest cities are high in international comparison—particularly in the services industry (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Turkey’s biggest cities are increasingly becoming productive service hubs, 2012 ($1,000 per worker)

Source:

Oxford Analytica Global Cities project

Still, Turkey faces three important policy challenges to ensure Turkey’s cities turn from being engines of growth to becoming magnets for the attraction of global talent and hubs for greater innovation and productivity growth.

- First, the urban redevelopment model that used valuable public land in city centers to lubricate investments in a combination of social housing and commercial real estate at no additional cost to the budget may have run its course. Land is becoming scarcer and trade-offs between multiple demands on urban land use are becoming sharper. New forms of government support and intervention are needed to mediate these trade-offs.

- Second, public policy could create substantial additional value through better planning and a more transparent system for the allocation of land development rights. For instance, the provision of public transport not only helps relieve the problems of congestion, it also significantly enhances land values, a gain that could be captured through property taxes or the auctioning of land development rights to help finance public priorities, including social housing and the provision of services. The World Bank is working with the authorities and a number of other development partners including the European Union on a Sustainable Cities investment and technical assistance project that aims to support better urban planning and the use of public investments to leverage sustainable urban growth.

- Third, the economics of agglomeration are likely to continue to benefit Turkey’s more dynamic and advanced cities over less well connected and less densely populated areas. To further reduce regional inequities, the government will need to continue to transfer resources to the poorer regions. In addition to central government investments in transport, health and education, there is scope to rethink and strengthen transfers from the center to local governments, in parallel with measures to strengthen municipal autonomy, governance and accountability.

Turkey’s policymakers need new tools to better plan and shape the next phase of Turkey’s urbanization. In one important respect, however, it will continue to be Turkey’s cities themselves that will shape the country’s development and policy agenda; the adaptation to urban lifestyles is precipitating changes in people’s social norms and values that have important implications for a host of development issues, from female labor force participation and education and fertility decisions, to savings and consumption preferences. Turkey cities are indeed cauldrons of social change, introducing lifestyles, aspirations and preferences that are turning Turkey into a modern society as well as a modern economy. Given the pace at which it is taking place, this process is likely to provoke debate and sometimes tension. The challenge for Turkey’s politicians will be to ensure such debate remains open and that the views of all can be heard. I look forward to coming back often and seeing Turkey’s cities evolve and shape their country’s future.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Building sustainable cities with Turkey’s urbanization agenda

June 9, 2015