The Libertarian Party has a historic opportunity in this year’s presidential election. The two major political parties appear to be settled on candidates who are each disliked by a larger share of the electorate than any other nominee in recent American history. With no significant independent candidacy on the horizon, Libertarians are the best organized alternative available to voters, including having ballot access in all 50 states. Merely as a result of these conditions, the Libertarian Party will far surpass the record 1.3 million presidential votes it garnered in 2012. On top of that, by nominating Gary Johnson and Bill Weld, two former Republican Governors with good track records governing in blue states, Libertarians seem to be embracing their chance at relevance. There is a non-trivial chance that they could be included in this fall’s nationally televised debates.

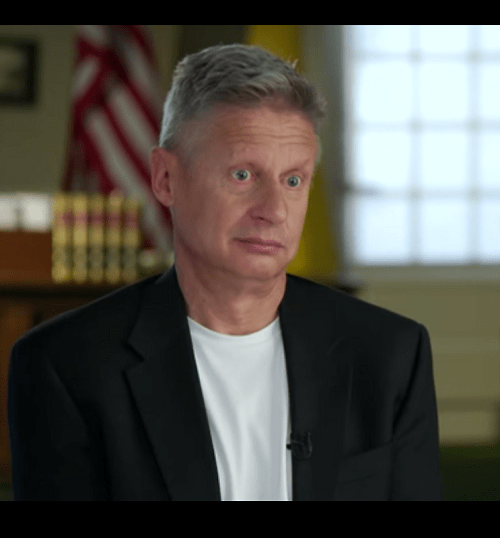

And yet, to this point, there is a sense that Libertarians are missing their moment. In almost all of Johnson’s recent television appearances, he seems intent on broadcasting two messages to the electorate: (1) “Hey, I exist!” and (2) “You may not realize it yet, but you might agree with our bundle of policy preferences—which are fiscally conservative and socially liberal—more than with the other candidates’ preferences.” This is offered up in an arch, almost jocular tone—as if Libertarians are hoping to win voters who look at politics and just want to lighten up. The (admittedly funny) faces that Johnson made on Samantha Bee’s Full Frontal illustrate the dominant note:

Unfortunately, 2016 is not a funny year for politics, and so Johnson’s “aw shucks, you just might like our policies” routine is squandering his adopted party’s best chance to build itself into a serious political force. The Libertarian Party always runs the risk of seeming like an expressive vehicle for the quirky and quixotic—the Libertarian convention, in May, featured a strip tease, and if you happen to live in Arkansas State Senate District 26, you can vote for Libertarian candidate Elvis Presley—rather than an organization that aspires to be a serious participant in the political process. Johnson’s recent performance plays right into that image.

Creating an alternative image would be quite straightforward in the current political moment. The Libertarian message to voters in these troubled times should be: “Our two main parties both subscribe to philosophies of government that don’t solve problems and lead to frightening stagnation, resentment, and abuse—a fact that should be more and more obvious each day. If elected, our party would forge a different path, one truer to our nation’s constitutional tradition of limited constitutional government; one better able to cope with the fiscal challenges facing our country in the coming decades; and one that offers fresh, incisive thinking about how to move America forward.”

(One benefit of emphasizing the importance of limited government, rather than Libertarians’ social permissiveness, is that doing so will help the party draw more voters from the ranks of Republican voters than from Democrats. While Libertarians might or might not want to adhere to that strategy over the long term, in the short term it would ensure that Johnson avoids becoming the Ralph Nader–style spoiler who puts Donald Trump in the White House.)

Beyond outlining these general commitments of libertarianism, Johnson needs to do a better job helping voters imagine how Libertarians can fit into the worlds of American politics and policymaking as we find them today. Are voters for Johnson supposed to think of themselves as completely rejecting the administrative state and its many functions, or are they supposed to think of Libertarians as offering a governing agenda that would focus, discipline, and even improve the federal government, even as it aims to shrink it? Will Libertarians’ penchant for ideological consistency make it impossible for them to function in a country where very few citizens hope for minarchy?

In this vein, I agree with Shikha Dalmia, who argues: “Johnson’s pledge that as president he’d veto any budget with a deficit just doesn’t cut it. It won’t persuade voters that he’s serious and it won’t affect the terms of the debate.” Johnson and Weld need to paint Libertarians as capable of being more than naysayers. Johnson sometimes quite reasonably emphasizes that much would hinge on what Congress would do, but he needs to give a sense of how he would seek to work with a House and Senate that would include not a single member of his own insurgent party.

Thinking beyond Johnson’s current campaign, which is obviously unlikely to end with an outright victory in November, Johnson and Weld should also think about the future of the Libertarian Party as a party. Politico reports that it has just 13,000 dues-paying members nationally, although it has succeeded in increasing its national registration to 411,250 over the last decade. That is a start, but only a small one in a country with nearly 220 million eligible voters. Will Libertarians go beyond saying that people might like casting a presidential ballot for their candidates and try to make the sale that their party can become a durable, workable vehicle for improving our public life?

There is just as much room for growth when it comes to candidate recruitment and support. Right now, the Libertarian Party website tells aspiring candidates: “If you think you have a chance of winning an election, or if you would at least enjoy trying, please do that.” That is…not a terribly effective way to try to field a slate of candidates across the country who can educate voters about the party’s positions and eventually gain access to the levers of governmental power. The party needs to use its moment of national exposure to build up its organizational structure and fundraising capacity, but it isn’t clear whether it can reconcile that necessity with its free-wheeling self-image.

Libertarians must decide: will they take the steps necessary to allow their party to mature, such that they might eventually follow the UK’s Liberal Democrats in becoming serious players in national politics, or do they prefer to stay on the Peter Pan path?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What does the Libertarian Party want to be when it grows up?

July 7, 2016