Generational trends forecast continued gridlock and partisan rancor in the 114th Congress that opens on January 6.

During the past two decades, Baby Boomers (born 1946-1964) first shaped and eventually dominated both the way Congress operates and its output, or lack thereof. Given their numbers and the traits that characterize many Boomers, the cohort can be expected to continue its Congressional ascendancy for the next decade or more. During that period Congress is likely to behave pretty much as it has during this century.

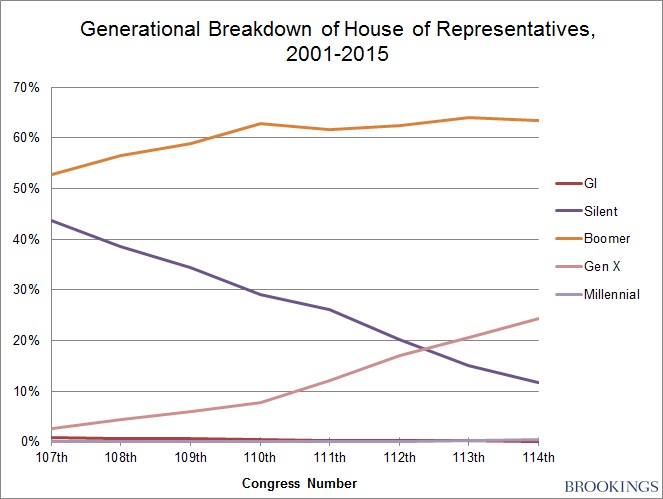

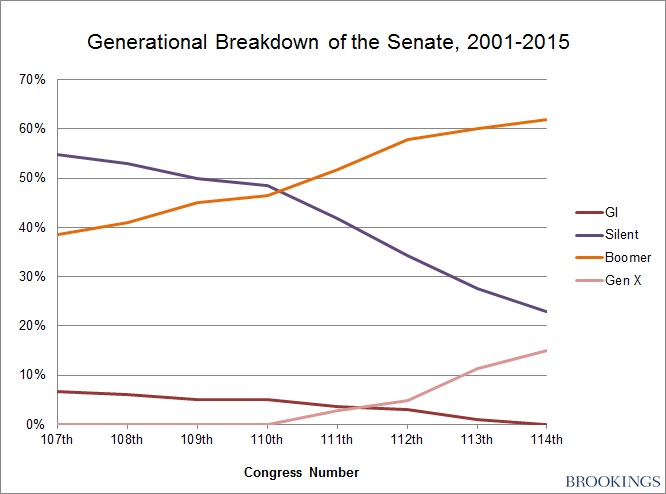

Boomers became a majority in the House of Representatives in the 1998 midterm elections. In the 107th Congress, elected in 2000, 53 percent of all Representatives were Boomers. The generation also attained a Senate majority (52%) in 2008. In the 114th Congress, Boomers will comprise nearly two-thirds of the members of both the House (63%) and the Senate (62%).

Boomers are of a generational archetype labeled “Idealist” by generational analysts. This type of generation is often indulged by their parents and encouraged to develop strongly held personal values. As a result, members of Idealist generations uncompromisingly adhere to their deeply held principles all of their lives. This pattern produces a challenge for the American political system, which is constitutionally based on institutions that require compromise and coalition-building to get things done.

Having rigid ideologues in charge of Congress would be problem enough, but Boomers, like many Idealist generations before them, are also deeply divided about what values are right and which are wrong. This is reflected in their voting behavior as well. In the 2004, 2008, and 2012 presidential elections, exit polling showed a narrower margin between the parties among Boomers than any other cohort. As a result, the primary political output of the divided Boomers has been frustrating gridlock and historically low evaluations of congressional performance.

The Boomers are not the first Idealist generation to be deeply divided. In the two decades before the Civil War, the dominant Transcendental generation (born 1792-1821) was consistently and increasingly deadlocked about how the United States should deal with the major question of the day, slavery. Ultimately, that issue had to be resolved on the battlefield when all Congressional and judicial attempts to decide the issue failed.

In the 1868 election, just three years after the Civil War ended, the electorate, horrified by the carnage of that conflict and tired of the endless debates over the issue that caused the war, swept the Transcendental generation from political dominance. Prior to that election, in the 40th Congress (1867-1868), Transcendentals held 56 percent of congressional seats and the younger Gilded generation (born 1822-1842) the remaining 44 percent. Those numbers were reversed in 1868. In the 41st Congress (1869-1870), the Gilded generation held 57 percent of Congressional seats and Transcendentals, 43 percent.

But such a generational tsunami is unlikely to be repeated in an age of poll driven, media saturated politics. Furthermore, the presence of the modern day generation most inclined to compromise, Silents (born 1925-1945), will continue to shrink as time goes by. They will comprise only 12 percent of Representatives and 23 percent of Senators in the 114th Congress, compared to nearly 50 percent in Congress when Boomer leaders, President Bill Clinton and Speaker Newt Gingrich, found a way to compromise on meaningful legislation.

Instead it is more likely that the process by which Boomers lose their congressional dominance will be difficult and protracted. For one thing, most members of Idealist generations do not leave their positions of power or withdraw from ideological conflicts willingly. Since Boomers will comprise two-thirds of both the Republican (64%) and Democratic (63%) delegations in the 114th Congress, most of them are likely to believe that voluntarily withdrawing would concede the moral and political high ground to their opponents.

So the most likely way Boomers will eventually relinquish power is through the passage of time when they are replaced by younger generations with different beliefs about the most effective way of governing. This has begun to happen already. In the 114th Congress, about a quarter of the House and 15 percent of the Senate are from Generation X (born 1965-1981) and two members of the Millennial generation (born 1982-2003) will serve in the new House.

Gen-X’ers, labeled a “Reactive” generation, are characterized by distrust of most institutions and ideologies, but they also possess a streak of pragmatism that prompts them to search for workable solutions to specific issues. Millennials, called a “Civic” generation, tend to be group-oriented and tolerant of differing beliefs and behavior, causing them to search for widely beneficial win-win solutions to problems. It will take a few years, perhaps a decade or more, but it will be those emerging generations that will end Boomer political dominance and put Congress—and the nation—on a less acrimonious and more productive political path.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Boomer Dominance Means More of the Same in the 114th Congress

January 5, 2015