When Jeb Bush announced he was exploring a run for President, TIME warned that Bush was “going to have to win over the Republican conservative base, which hates Common Core with the fire of a thousand suns.” In case conservative loathing of the Common Core ran the risk of being understated, the Washington Post weighed in with an analysis stating that “The conservative base hates—hates, hates, hates—the Common Core education standards.”

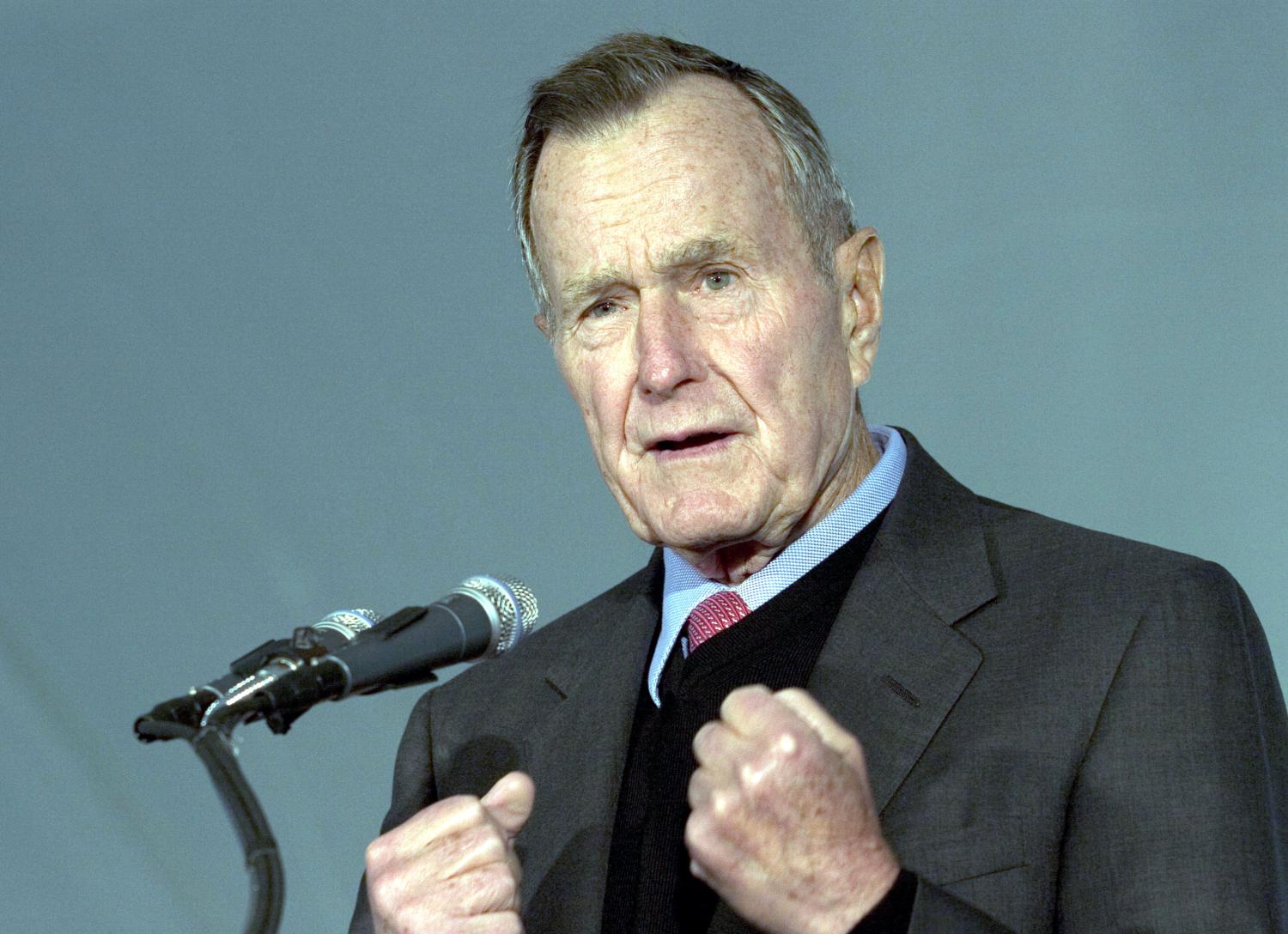

That media shorthand vastly oversimplifies not just the debate among conservatives over the Common Core but the rich, conservative roots of the standards themselves. As I show in a new Brookings paper, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) embody conservative principles in setting goals for student learning that date back to Ronald Reagan. In fact, compared to his predecessors in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations, U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has substantially shrunk the federal role in advocating for anything resembling a model national curriculum, national standards, and national assessments. Implementation of the Common Core standards is still proceeding in more than 40 states in no small measure due to the fact that the Obama administration did not repeat the federal overreach of their GOP predecessors by funding the development of national standards and model curriculum.

The conservative roots of the Common Core are little known today. Even among reporters who cover the education beat, few are familiar with, and even fewer have written about, the 47-page secondary school model curriculum guide and the 62-page elementary school curriculum guide that William Bennett, Ronald Reagan’s secretary of education, wrote and the Education Department published in 1987 and 1988. Nor have reporters recounted, except in passing, the sweeping, self-described “crusade” that Senator Lamar Alexander launched to promote national standards and voluntary national assessments when he was secretary of education in the elder Bush’s administration.

George H.W. Bush’s America 2000 plan, which Lamar Alexander personally helped to craft, was a remarkably ambitious reform program that makes Barack Obama and Arne Duncan’s efforts to encourage voluntary state adoption of the Common Core standards look timid. Unlike the Obama administration and Secretary Duncan, Secretary Alexander supported the development of voluntary national standards developed with federal funding, for seven subject areas (English language arts, science, history, geography, arts, civics, and foreign languages). And unlike the Obama administration’s Race to the Top program, the America 2000 plan would have dramatically increased the existing testing burden in schools by creating 15 new national tests (five tests in core subjects in three grade levels). Secretary Alexander himself called the federally-funded development of national standards “the most comprehensive rethinking ever of what we teach.”[i]

Secretary Alexander believed in a limited yet muscular federal role in K-12 education. At the April 1991 unveiling of the America 2000 plan, Alexander pledged that the federal “role will be played vigorously. Washington can help by setting standards, highlighting examples, contributing some funds, providing flexibility in exchange for accountability, and pushing and prodding—then pushing and prodding some more.”

The stark difference in outcomes between the America 2000 plan (which died quietly in Congress) and the CCSS stems from the fact that the leaders of the Common Core movement learned from and avoided many of the political missteps committed with America 2000. Instead of seeking federal funding and input in developing the Common Core standards, governors and chief state school officers scrupulously kept the federal government out of the process of drafting the standards. Instead of trying to set standards for teaching politically sensitive subjects like U.S. history, the CCSS honed in on just English Language Arts and math. And instead of outlining model curriculum, the federal government remained mum about selecting curriculum.

In many respects, the story of the evolving conservative role on the Common Core is rife with irony and sweeping role reversals. If Lamar Alexander can lay claim to being the original political godfather of the Common Core State Standards, his Assistant Secretary at the department, Diane Ravitch, is their intellectual godmother. During her 18-month stint at the department from 1991 to 1993, Ravitch’s chief assignment was to make the case for national academic standards. After leaving the Education Department, she wrote a 186-page citizen’s guide for the Brookings Institution advocating for national standards. (Today, Ravitch is a leader of the progressive opposition to the Common Core).

Contrary to Tea Party claims, and numerous statements by GOP presidential candidates, the Common Core State Standards do not constitute a federal takeover of what is taught in schools or a national curriculum—dubbed so-called “Obamacore” by some conservatives. These fabricated claims are not mere exaggerations of the facts but rather constitute the use of the “big lie technique”—as Sol Stern, a conservative education scholar at the Manhattan Institute, puts it.

The truth is that the Common Core standards tilt heavily toward conservative pedagogical traditions in their rigor, their call for content-rich curriculum, their emphasis on the development of literacy in history, civics, and foundational documents of American democracy, and their expectation that students will use evidence from readings in persuasive writing and class discussions. The Common Core State Standards are thus a classic case of conservatives not taking “Yes” for an answer.

The adoption of higher standards through the Common Core is a major advance for America’s students. But it is still too early to tell if raising standards will necessarily lead to better outcomes for students and more enriching teaching opportunities for educators—though preliminary indications are that CCSS is leading to higher performance standards, and is increasing student achievement and boosting college-readiness.

If conservatives abandon the false narrative that the CCSS constitutes a federal takeover of what is taught in schools, they could play a leading role in ensuring that the CCSS is implemented with fidelity to conservative principles. But in the end, the paramount litmus test in the debate over the Common Core should be a comparative one: Does the CCSS accelerate and deepen student learning and does it boost career- and college-readiness, compared to the previous system of 50 differing state standards? Maintaining political purity, fostering fealty to federalism, or opposing all-things Obama are important goals for many conservatives. Yet those factors shouldn’t ultimately matter more in assessing the Common Core than examining its actual impact on students.

In a 1995 essay on her experience in developing national standards, Diane Ravitch warned that “Educators have an unfortunate habit of making the best the enemy of the good, thus beating back any proposed reform that does not promise to solve all problems simultaneously.”[ii] The vast majority of states have stood by the Common Core, and so far refused to let the best become the enemy of the good. Today, it’s time for conservative critics of the Common Core to stop rewriting history, halt the maelstrom of misinformation on the Common Core, and pivot away from pandering to political prejudices. And it’s time for conservatives to start reasserting a leadership role in improving the implementation of the Common Core for the betterment of the nation’s students.

[i] Lamar Alexander, “What We Were Doing When We Were Interrupted,” in John F. Jennings, ed., National Issues In Education: The Past is Prologue (Phi Delta Kappa and the Institute for Educational Leadership, Bloomington, Indiana and Washington, DC, 1993), p.16.

[ii] Diane Ravitch, “The Search for Order and Conformity: Standards in American Education,” in Diane Ravitch and Maris A. Vinovskis, eds., Learning from the Past: What History Teaches Us About School Reform (The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1995), p. 188.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).