When the United States ended the draft and transitioned to an all-volunteer military in 1973, there was concern about who would join and whether the transition would negatively impact the quality of the force, which many suspected it would.

As it turns out, the quality of the force as a whole actually increased over time. In 1977, 27.1 percent of new enlisted recruits met the military’s standard for being “high quality,” meaning that they possessed a high school diploma and above-average intelligence relative to the U.S. population as a whole. Decades later, at the height of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, 60 percent of new enlisted recruits met the high quality standard.

But what about military officers? Though commissioned officers comprise only about 16 percent of the force, they clearly have a major impact on the success of the military as a whole given their leadership role for their troops and responsibility for strategy and tactics.

So are today’s officers up to the task? In new research, Brookings’ Michael Klein and Tufts University’s Matthew Cancian—a former Marine officer who served in Afghanistan—take a closer look at this question and uncover a troubling pattern.

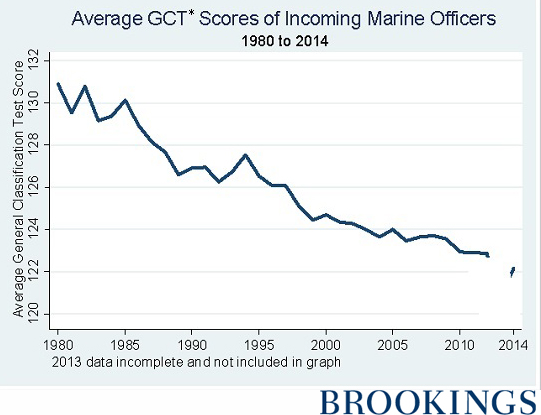

After analyzing test scores of 46,000 officers who took the Marine Corps’ required General Classification Test (GCT), Klein and Cancian find that the quality of officers in the Marines, as measured by those test scores, has steadily and significantly declined over the last 34 years.

The General Classification Test (GCT) from World War II to present day

So what exactly is the GCT, and how are the scores used by the U.S. military? The GCT dates back to World War II, when it was developed to help classify incoming servicemen. Designed to have a mean score of 100, with a standard deviation of 20, 120 was used as the bar for entry into Marine Officer Candidate School (OCS).

After World War II, the military replaced the GCT with the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB). The Marine Corps, however, still administers the GCT to officers at The Basic School (TBS) because it strongly predicts their success there.

TBS is a six-month course that all Marine officers attend after completing two prior requirements: Obtaining a four-year college degree and attending Officer Candidate School.

GCT scores over time

Through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the Marine Corps, Klein and Cancian received data on the GCT scores of all officers—46,000 altogether—from Fiscal Year 1980 to Fiscal Year 2014.

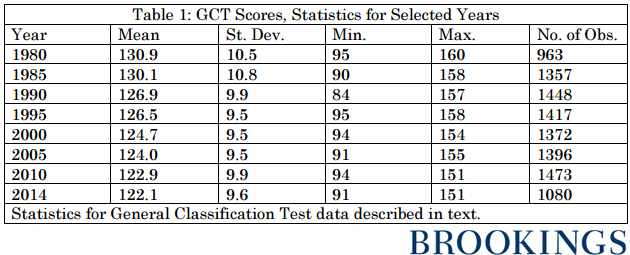

After analyzing the data, the authors uncovered a startling trend: A statistically significant decline in scores over the past 34 years, the magnitude of which, the authors say, “is relevant given the distribution of the scores.”

Other key findings include:

- Eighty-five percent of those taking the test in 1980 exceeded a score of 120, which was the cut-off score for officers in World War II. In 2014, only 59 percent exceeded that score.

- At the upper end of the distribution, 4.9 percent of those taking the test scored above 150 in 1980 compared to 0.7 percent in 2014.

- Over 34 years, the average score decreased by 6.6 percent, from 130.9 to 122.1.

- Taken together, the 8.2-point drop in average score represents 80 percent of an entire standard deviation’s decline (from 10.5 in 1980 to 9.6 in 2014). In other words, today’s Marine officers scored nearly an entire standard deviation worse, on average, than their predecessors 34 years ago.

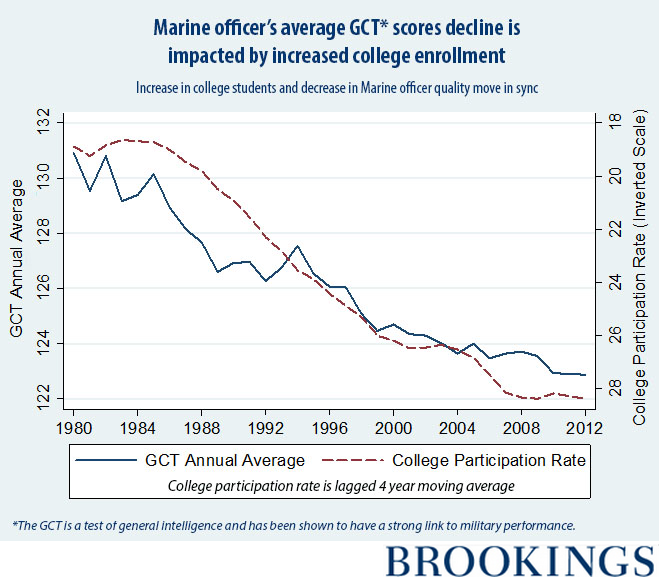

Why more Americans going to college might be having unexpected effects on officer quality

So what’s causing this steady decline in GCT scores? According to Klein and Cancian, the decline in officer quality might actually have to do with the fact that more people are receiving college degrees than ever before: The authors note that the decrease of GCT scores over time correlates to an increase in the college participation rate during that same period.

A four-year degree is required to become an officer. Therefore, the authors posit, as more people who may not have obtained four-year degrees in the past receive them, more people who would otherwise not be eligible for commissions become viable applicants. Because the decline concerns all college graduates, it has likely also impacted the other military services.

Klein and Cancian also address claims that changing demographics in the military may be driving the decline in scores. In particular, the authors look at the effects of a higher proportion of women and Hispanics in the force, as well as the military’s efforts to actively recruit more African-American officers.

What they find very much disputes claims that affirmative action or changing demographics have played any role in declining officer quality: “We find, in fact, a positive association between African-American officers and mean GCT score, perhaps because recruitment efforts by the Marine Corps have attracted minority officers who are more qualified than the typical college graduate,” say Klein and Cancian. The authors also note that the proportion of Hispanic officers has no statistically significant impact on the decline in score.

Today’s less qualified officer candidates will be tomorrow’s senior military leaders

Klein and Cancian stress the importance of acknowledging and reversing the decline in officer quality as measured by the GCT score not just for the short-term impacts it has. The junior officers of today will become the generals of tomorrow; if the military does not receive the intelligent young leaders today that it used to receive in the past, it will not have high quality generals in the future.

“What has been the impact of this drop in quality on the effectiveness of the military? Answering this question is beyond the scope of this paper. Given the myriad studies associating performance with intellect, however, it is hard to imagine anything other than a seriously deleterious impact on the quality of officers and, by extension, on the quality and efficacy of the military,” say the authors.

Read Klein and Cancian’s full paper here »

Nicholas Buchta contributed to this post.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Understanding the steady and troubling decline in the average intelligence of Marine Corps officers

July 24, 2015