Lessons learned from

Economic Impact Payments

during COVID-19

The three rounds of Economic Impact Payments (EIPs, also known as stimulus checks) disbursed between March 2020 and April 2021 were significantly larger than similar payments made in the past—amounting to more than $800 billion in total. Intended to provide broad insurance, these payments were distributed to all but the highest-income households, phasing out beginning with adjusted gross income of $75,000 for singles and $150,000 for married families. The first round, provided by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) in March 2020, provided $1,200 to each adult with an additional $500 for each child under age 17. The second round in January 2021 disbursed $600 per adult with an additional $600 per child and the subsequent round in March 2021 sent out $1,400 per adult and another $1,400 per child. Over roughly a year, EIPs provided the equivalent of more than 125 percent of median monthly income for a four-person household with two married adults and two children.

Recession Remedies podcast episode: How did COVID-19 Economic Impact Payments affect households and the economy?

Evidence on Economic Impact Payments

- Studies analyzing the spending response to the EIPs show similar or smaller responses compared to previous rebate checks. This may be the result of the size of the checks, fewer spending opportunities as consumers stayed home due to COVID-19 restrictions, higher liquidity from other government benefits, and increased saving due to uncertainty.

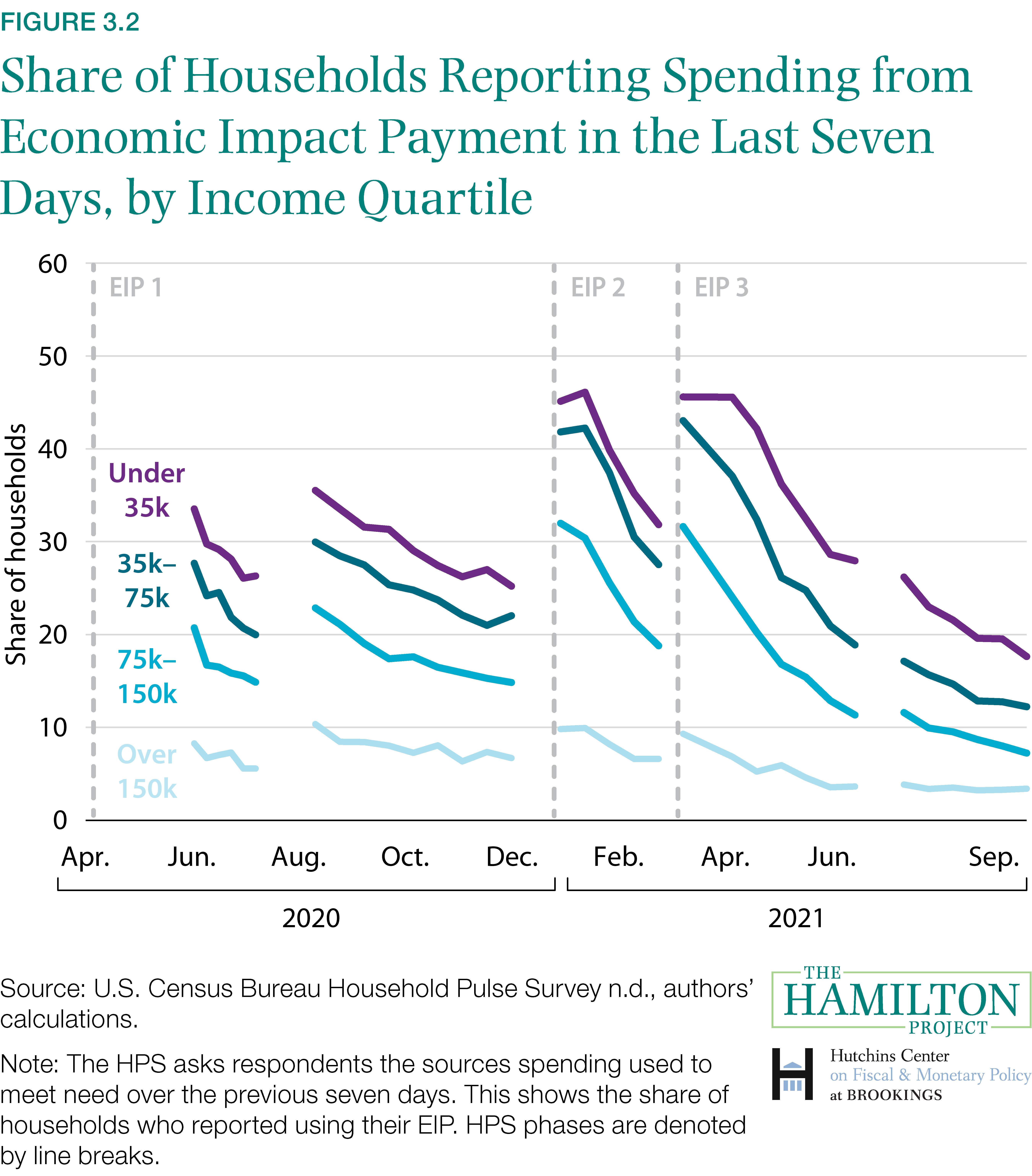

- Households with less liquidity spent more of their payments sooner than others, meaning they had larger and more front-loaded marginal propensities to consume (MPCs).

- While the highest-income households primarily used pre-pandemic income sources to meet spending needs in June and July 2020, lower-income households were more likely to report relying on EIPs, Unemployment Insurance, and borrowing from friends and family.

- Households with income losses were more likely to spend their EIPs, even for those with higher incomes, where 15 percent of households with prior incomes over $100,000 who had suffered income losses reported saving their first EIP, compared to 35 percent who had no income loss. The gap was less stark for households earning under $25,000: 2 percent for those with income losses versus 7 percent among those without.

- Households with lower incomes were less likely to receive EIPs relative to higher-income households who were eligible; 89 percent of married households with under $25,000 in 2019 income reported having received or expecting to receive an EIP, compared to 93 percent with incomes between $100,000 and $150,000.

- 40 percent of those not receiving an EIP did not file a tax return or receive Social Security benefits; while 50 percent of nonrecipients under the poverty line did not have bank accounts.

Lessons Learned from Economic Impact Payments during COVID-19

The government’s ability to inject cash into the economy quickly, especially when compared to past reliance on mailing paper checks, shows that fiscal policy can be implemented rapidly with minimal transaction costs. The use of electronic disbursement dramatically shortened the period between the signing of the legislation and the initial arrival of payments.

For the first EIP, it took about two weeks for the Treasury to send the first direct deposits out. Over the subsequent EIP rounds, the gap between signing the bills enacting the EIPs and the disbursement of funds narrowed even further. The second EIP narrowed that gap to about one week while the third EIP’s first batch of payments were made the day after the legislation was signed. The first round of EIPs provided needed liquidity to households to cover necessities, particularly inducing spending among households reporting lost income and low liquidity. Eligibility for EIPs was not contingent on minimum income requirements, which allowed the lowest-income households to access payments. Yet, coverage gaps were still evident, related to differences in rates of tax filing, receipt of benefits from certain federal programs, and access to traditional bank accounts. During future crises, to meet the objectives of bolstering aggregate demand and relieving hardship among the most affected households, payments would be better targeted if aimed at households who have lost income or who are in danger of losing income, i.e., those who often have the highest MPCs.

The use of electronic disbursement dramatically shortened the period between the signing of the legislation and the initial arrival of payments.

While coverage gaps and delays in payments did affect some households, the EIP program successfully provided immediate support directly to households, including those waiting on delayed Unemployment Insurance benefits. Investment by federal and state agencies to build better data systems for program participation, administrative earnings records, and tax returns, would provide clarity on how EIPs and other programs worked during the pandemic and would allow better targeting in future episodes. With that information in hand, policymakers can use EIPs as an effective and efficient way to quickly help people for whom other support is delayed or insufficient.

For more information or to speak with the authors, contact: