Lessons learned from the breadth of economic policies during the pandemic

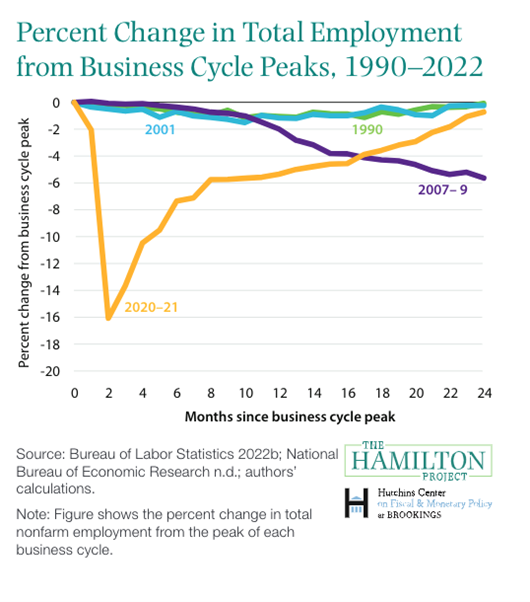

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the sharpest and most synchronized reduction in global economic activity in history. The U.S. economy experienced a V-shaped recovery of a type not seen in recent recessions. The rapid recovery was due to two factors. First, the recession itself was caused by a shock associated with COVID-19; as that shock retreated—and people learned to better live with the pandemic—the economy was poised to recover quickly, just as it typically does after natural disasters. Second, the policy response protected household incomes and kept many businesses intact so that they were in a position to resume more normal levels of economic activity when it was safe to do so.

Recession Remedies podcast episode: What should we learn from the economic policy response to COVID-19?

Real disposable personal incomes actually rose in 2020 and 2021 as transfer payments from the government vastly exceeded lost incomes from other sources. As a result, poverty, after accounting for taxes and transfers, fell in 2020 to the lowest level since the data series began in 1967. Initially, observers and policymakers worried that a cascade of bankruptcies and defaults could precipitate a financial crisis. But improvements to make the financial system more resilient in the wake of the global financial crisis and the policy response to the COVID-19 crisis quickly addressed potential issues.

The economy experienced major side effects from the pandemic and associated policy response, most notably the highest inflation rate in 40 years, far outpacing the increase in wages and leading to the largest real wage declines in decades. Ultimately, the economic policy response to the COVID-19 recession should be judged not just by its consequences in the spring of 2020, not what happened over the next two years, but also by the longer-term effects, and whether the response will prove to have contributed to a stronger and more sustainable economy going forward.

Evidence on the COVID-19 economic policy response

- The initial fiscal response in the U.S. was large. It waned in mid-2020 and then surged again in late 2020 and early 2021.

- Economic Impact Payments, Unemployment Insurance, forbearance programs on mortgages and student loans, and an enhanced CTC played the largest roles in lifting household finances, while businesses received support largely through grants and subsidized loans.

- Even after the initial substantial fiscal assistance, observers generally expected a much slower economic recovery from the second quarter 2020 trough than actually came to pass.

- The U.S. government incurred substantial debt. Moreover, inflationary pressures and the efforts to moderate those pressures might bring an end to the expansion.

- The U.S. fiscal response appears to have been larger than any other country.

Lessons learned from the breadth of economic policies during the pandemic

Policymakers should take the lesson from the past two years that vigorous fiscal and monetary policy can boost income for most households and disproportionately for lower-income households and can speed economic recoveries. However, doing too much can have serious downsides that might be difficult to mitigate.

Macroeconomic support for an economy deep in recession with many underused resources can increase output and employment with little effect on inflation. But as the economy gets closer to its capacity, additional macroeconomic support will feed increasingly into inflation instead of improvements in output and employment. Going forward, the magnitude and timing of the response should be improved through more automatic stabilizers, and the targeting of the response should be as well. The good news is such responses can be implemented efficiently if policies are developed in advance of a crisis.

Policymakers should take the lesson from the past two years that vigorous fiscal and monetary policy can boost income for most households and disproportionately for lower-income house-holds and can speed economic recoveries.

It is important to draw lessons not just from what happened, but also from what did not happen during the COVID-19 recession: for example, there was no financial crisis in the United States or worldwide. The initial, robust response by monetary policy-makers was critical to keeping the financial sector on an even keel. Better preparation in the form of more robust and stress-tested balance sheets for banks prior to the recession also helped.

The preexisting social safety net is inadequate in the face of recessions: it is not generous enough and has too many gaps, which is why it needed to be supplemented by policy action both in the Great Recession and to a much greater degree in the COVID-19 recession. Additional automatic stabilizers are likely part of the answer but are unlikely to be sufficient to avoid the need for well-timed and wise discretionary fiscal responses in the future.

It is still not clear what policies would work better in the United States to lessen the impact of a GDP decline on employment and preserve worker attachment to their employers. Job retention schemes were heavily utilized in European countries compared to state-based work sharing programs in the U.S.—these programs should be explored in greater detail for future downturns.

For more information or to speak with the authors, contact: