The Great Real Estate Reset

Editor’s Note: For more info on content related to Community Ownership of Real Estate, please visit our page here.

The full effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. retail may not be fully clear for months. Many stores and restaurants have closed permanently, but some—especially those located in residential neighborhoods where more people are working from home—may benefit from the changes to people’s routines. What is clear is that that these new and powerful impacts on the sector are coming on top of much longer-term changes in how and where people shop.

Post-pandemic, every metropolitan area—but especially metro areas in the Midwest and the Southeast—will find themselves with surplus retail space in need of major capital investment for adaptive reuse. Short-term strategies to stabilize department-store-anchored malls will not last against long-term trends, and long-standing racial disparities in access to retail will reinforce structural racism at a time when the nation is crying out for racial justice. The industry and policymakers should view this as an opportunity to work together to create new opportunities for housing, institutional uses, and locally empowered retail entrepreneurship.

The trends

The COVID-19 pandemic comes at a pivotal moment in American retail. The sector is already facing dramatic stress and tectonic shifts from e-commerce, tariffs, and changing consumer preferences. Yet the real estate industry has struggled to produce the retail developments that match shifting demands.

Rapid e-commerce growth is disrupting the retail sector.

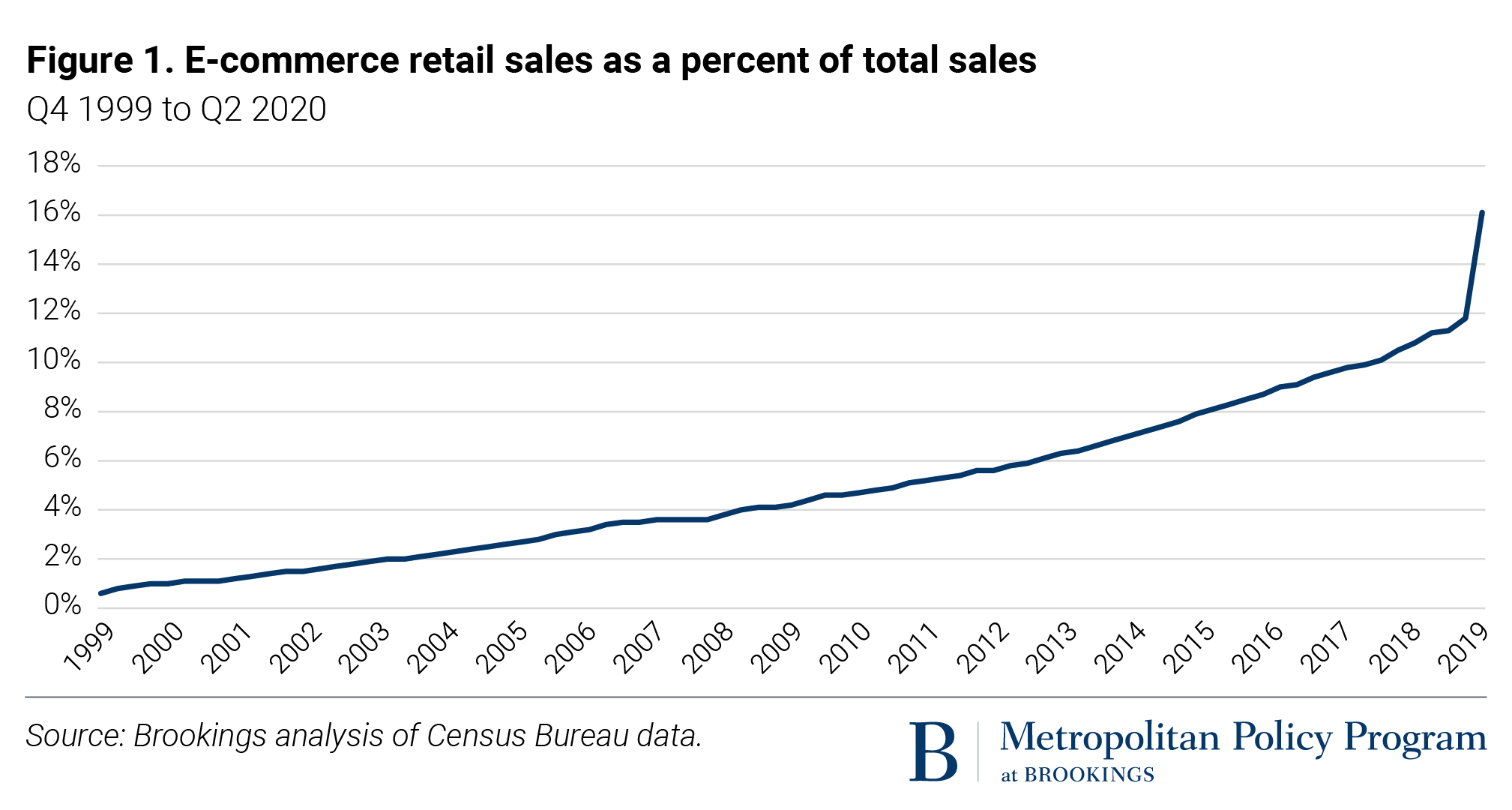

According to the Census Bureau, e-commerce retail sales have grown from $37 billion in the first quarter of 2010 to $200.7 billion in the second quarter of 2020—an average increase of 30% per year and an increase of 37% from the first quarter of 2020 (the last quarter before the pandemic). This growth corresponds to a major increase in e-commerce’s market share of all retail sales, from the low single digits 10 years ago to over 16% today.

Growth in e-commerce does not mean the end of brick-and-mortar stores, however. Trade analysts have noted a “halo effect” for hybrid (or “omnichannel”) retail enterprises, in which online sales grow in neighborhoods where retailers also have a physical presence. This is why big-box retailers like Target are opening smaller-format stores closer to where people live, while formerly online-only innovators like Warby Parker and Casper have introduced showroom storefronts. The location, format, staffing, and supporting logistics of brick-and-mortar retail are seeing intense innovation and experimentation.

Retail has shifted from neighborhoods to regional clusters, and from independent merchants to national or global brands.

The significant expansion of e-commerce retail is occurring alongside a decades-long retreat of neighborhood retail which has been driven, in part, by the rise of big-box stores and the demise of small retail firms. The share of goods sold by independent retailers in the U.S. has halved since 1980 and is now roughly one-quarter of the total. The total number of retail firms in the U.S. dropped by 5% between 2007 and 2017—from 1.13 to 1.06 million—even while the U.S. population grew by 8% in the same time frame. Meanwhile, the growing online retail subsector has become especially consolidated, with Amazon accounting for 35% of online sales and 51% of annual growth in online sales in 2015.

Retail retreat and consolidation have not played out to the same extent in all U.S. metropolitan areas.

In the big picture, the United States as a whole has too many shopping centers per capita compared to global peers like Canada (29% less), Australia (53% less), Japan (81% less), and France (84% less). However, the extent and form of the U.S. retail glut varies tremendously by metro area. Some metro areas, especially in the Midwest and Southeast, are relatively over-retailed at the regional level and under-retailed at the neighborhood level. Metro areas with the most square feet of retail per capita tend to have particularly low amounts of neighborhood retail, as measured by the average number of establishments per capita within census tracts. This relationship is shown in Figure 2, and the full list of six-digit NAICS codes that we classified as “retail” are in Appendix A. Our “retail” category includes an expansive list of commercial land uses that typically lease storefront space, including stores, restaurants, and doctor’s offices.

Even with all this retail, some neighborhoods are still underserved.

At the national level, neighborhood retail access is fairly even across income categories. However, significant disparities exist by race. Previous research has found that supermarkets are much more commonly located in high-income, majority-white neighborhoods than in low-income and majority-Black neighborhoods. Our analysis found that retail establishments in general are significantly underrepresented in African American communities regardless of income.

In the 192 largest metro areas in the U.S., across the full spectrum of income, we found that census tracts with a Black population share over 80% have less than half as many retail establishments per capita as tracts with a Black population share under 20%. Census tracts with lower incomes have more retail per capita—a logical finding given that these households are less likely to have access to a car. However, even though over three times as many Black households are carless compared to white households, tracts with higher shares of African American residents have less retail per capita across the board. These findings are consistent with previous research identifying “retail redlining” as a cause of structural racial disadvantage. Access to retail amenities is a key driver of home values, so this dynamic also contributes to the racial wealth gap.

Retail establishments in Black communities are often of a lower quality than those in white areas.

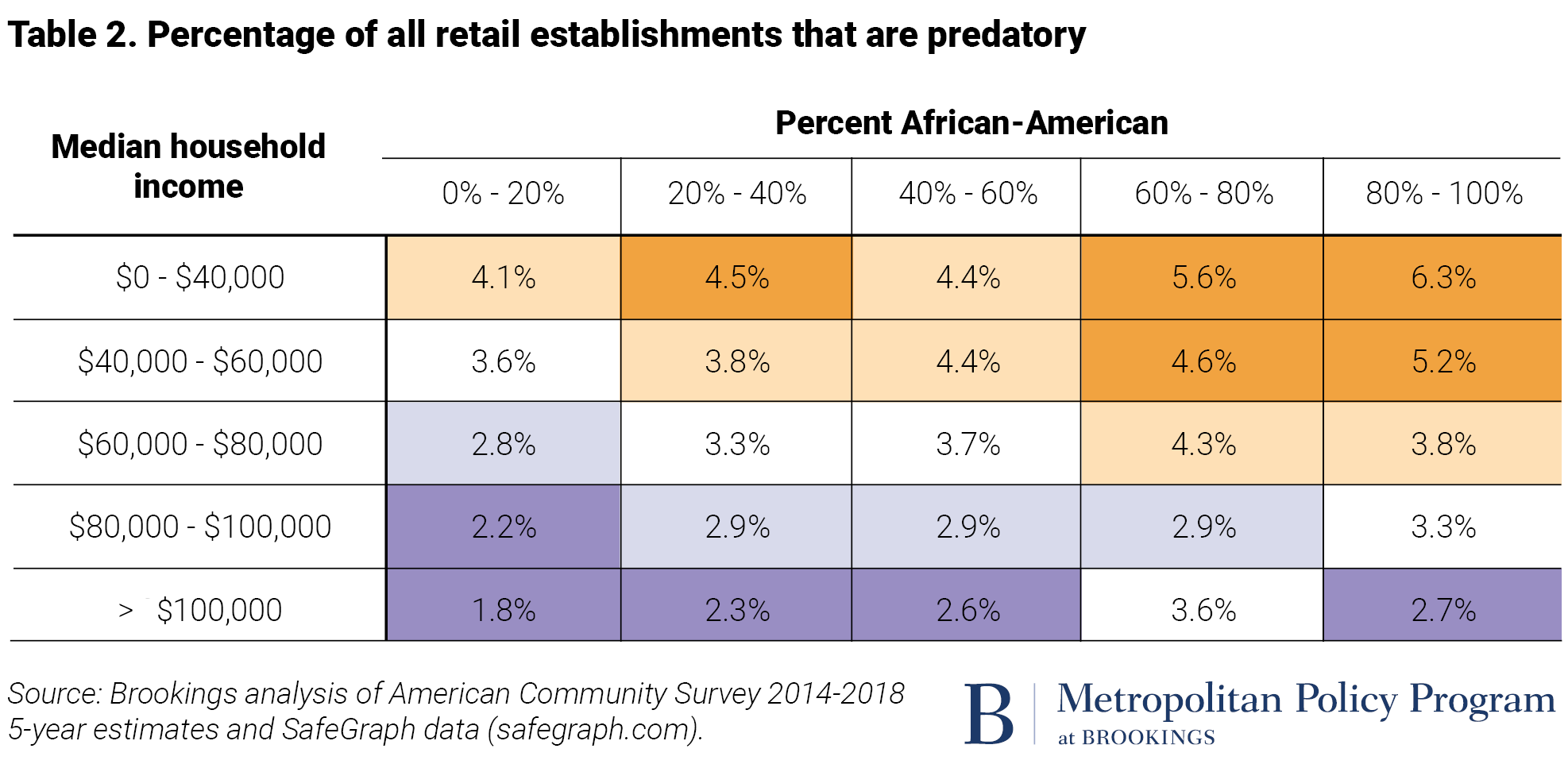

Only some types of retail are underrepresented in Black communities. Because conventional retail is underrepresented in Black communities, as shown in Table 1, the fraction of predatory retail establishments—liquor and tobacco stores, bars, payday loan and check-cashing centers, pawnshops, and dollar stores—is disproportionately high in majority-Black census tracts. This is the case at every income level. These predatory establishments are significantly more common in lower-income communities regardless of their racial demographics: They made up twice as large a fraction of retail establishments in tracts in the bottom quintile of income than of tracts in the top quintile of income. Table 2 shows the full distribution of predatory retail as a share of all retail by census tract by race and income.

The real estate industry has missed market opportunities for “walkable” retail.

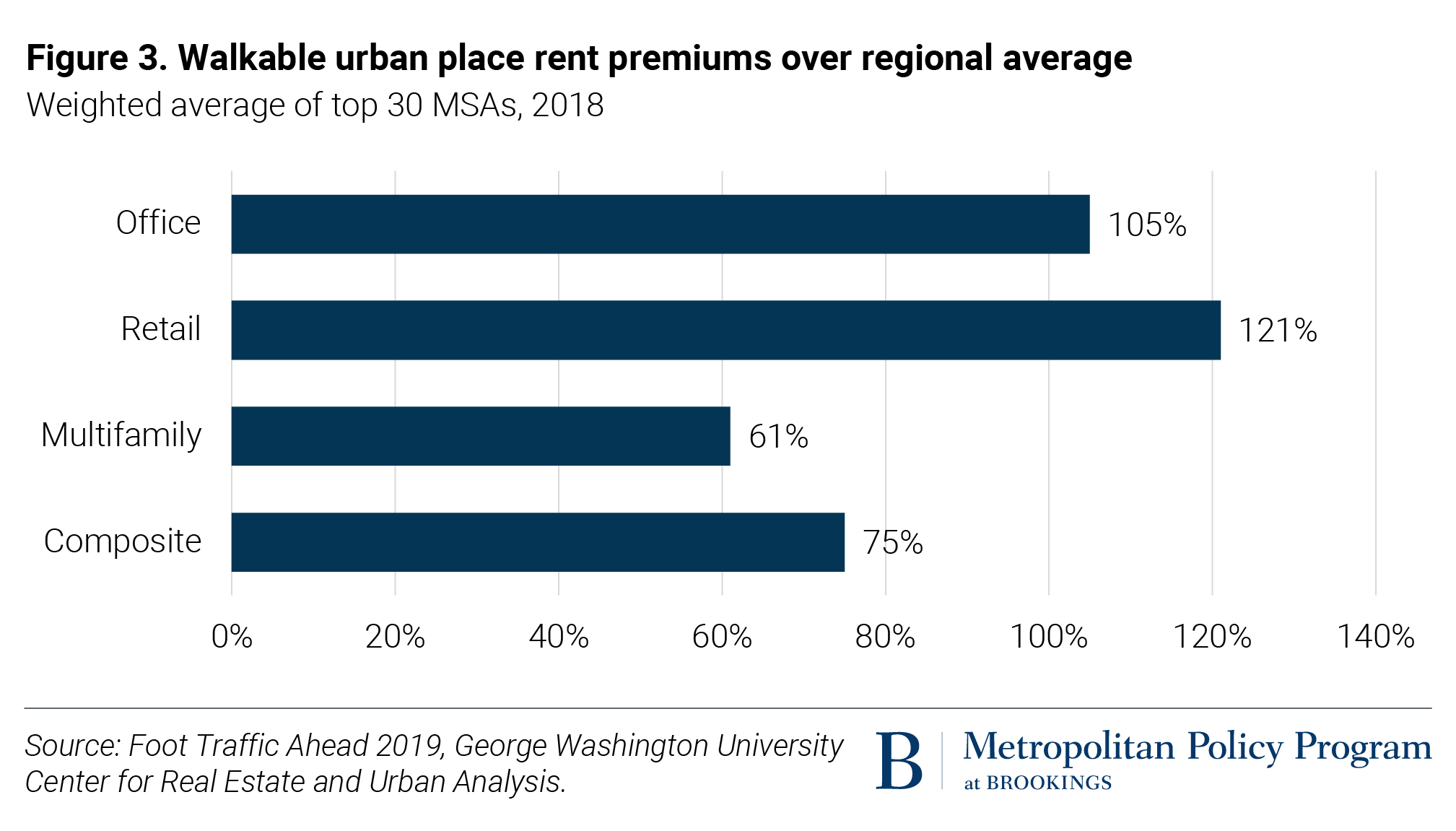

The real estate industry is visibly struggling to deliver usable retail products in the right locations. The relative absence of walkable retail in most American communities represents a market failure, given that retail leases in walkable urban places in large metro areas commanded 2.2 times the rents per square foot of the regional average in 2018, and that walkable commercial real estate premiums have increased 19% on average across the 30 most populous U.S. metro areas since 2010. Of all commercial real estate product types, retail commands the highest walkability premium. But despite this dramatic price signal, just 12% of retail square footage on average is located in walkable urban places across the 30 most populous metro areas.

Why these trends matter

The retail sector is going through a period of profound disruption. These trends have serious implications for both urban and suburban communities, which are grappling with very different sets of challenges related to retail supply and consumer needs.

At the regional level, dead malls have real potential for adaptive reuse, which is already happening. Their floor plates are far more adaptable to logistics, medical, or institutional uses than dated offices, and they are often sited in highly accessible locations. Ironically, these same floor plates are often more suitable for use as contemporary offices than typical older office inventory. Struggling suburban malls in high-growth metro areas can also allow for infill housing in their vast parking lots, especially malls with transit access. In particularly over-retailed slow- and no-growth metro areas and neighborhoods, the surplus is so great that retail uses are likely to be abandoned, and could be candidates for new ownership models inclusive of nonprofit, public institutional, or arts-based uses. However, the sheer scale of retail sprawl in those areas is such that contraction via demolition will be a necessary alternative to decay.

At the neighborhood level, the absence of the right retail spaces will continue to be an obstacle to retail innovation and equity. Neighborhoods with retail are more valuable and more resilient, so inequality will persist as long as all neighborhoods don’t have decent retail amenities. The relative absence of neighborhood retail in majority-Black neighborhoods hurts residents in these neighborhoods and often forces them to pay higher overall costs for necessities. The predatory retail that is more common in low-income and majority-Black neighborhoods is also harmful, because discount retailers often drive out more desirable establishments. The expansion of dollar-store chains in low-income neighborhoods and Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Asian American neighborhoods has highlighted this effect, with those chains pushing out grocery stores that sell a greater variety of fresh, healthy food.

The lack of retail within walking distance is a particular problem for people without access to vehicles, especially as the largest share of Americans in poverty now live in suburban areas, which tend to have limited access to transit. However, the absence of desirable local retail options in low-income and majority-Black neighborhoods does not necessarily mean that residents of these neighborhoods go without groceries or other necessities. Instead, it often forces them to commit more time to longer trips. This burden of additional travel time for shopping and nonwork trips also contributes to gender inequality, as responsibility for nonwork “care travel” often falls on women.

Finally, the absence of local retail (and especially locally owned retail) forces residents of majority-Black neighborhoods to shop elsewhere, robbing their local economies of the benefits of a strong small business ecosystem. Money spent locally puts dollars in the pockets of shopkeepers and store employees (as well as sales tax revenue in government coffers), who then make their own expenditures, kicking off another round of spending in a virtuous cycle. The value of this local multiplier depends upon the extent of “leakages”— the share of resulting spending that is not recirculated within the local economy—which in turn depends on whether purchases are made at locally owned or national chain retailers. Estimates by a leading business analysis firm suggest that purchases from local, independent retailers result in recirculation in the range of 50% to 70%, while local purchases from national chains yield less than 14%.

The nature and distribution of brick-and-mortar retail is no longer working for many people and places. As the sector continues to evolve, retailers, landlords, and communities all stand to benefit if the real estate industry—in partnership the public sector—gets smarter about how to build products that better serve consumers in both urban and suburban areas.

The authors thank Chris Zimmerman and Jordan Howard for their assistance in researching this piece.