The Great Real Estate Reset

Editor’s Note: For more info on content related to Community Ownership of Real Estate, please visit our page here.

The United States is the second-largest producer of carbon dioxide emissions globally—the effects of which are coming home to roost, quite literally, in our own backyards. Climate change is already impacting every region of the United States, with serious consequences for real estate and infrastructure, including property damage from extreme weather events, lost habitable land due to flooding, extreme heat, and dwindling water supplies.

But our built environment isn’t merely suffering from these challenges—it’s also contributing to them. Decades of low-density, auto-centric development—fueled by restrictive land use regulations—have been increasing transportation-induced emissions and restricting people’s ability to live in communities with low environmental risks and high economic opportunity.

Climate change’s growing and varied risks have near-term implications for the market viability of the real estate industry’s dominant financing and development models. Over the longer term, a failure to mitigate these risks will fundamentally reshape global economies, upend social and cultural ecosystems, and redefine the human experience in the built environment for generations to come.

The trends

Over the past century, a number of economic factors, demographic shifts, and land use decisions have dramatically increased both our emissions and climate risks, while at the same time making living and working in communities of opportunity increasingly unattainable.

The U.S. is growing the most in the places that are most vulnerable to climate change.

For the last 60 years, U.S. economic and population growth has coalesced around the nation’s biggest metropolitan areas, leaving the rest of the country and its small communities behind. The innovation economy has fueled the migration and concentration of the college-educated young adult millennial generation and baby boomers to tech-centric and “outdoorsy” cities like Seattle and Denver, as well as better-weather destinations across the Sun Belt.

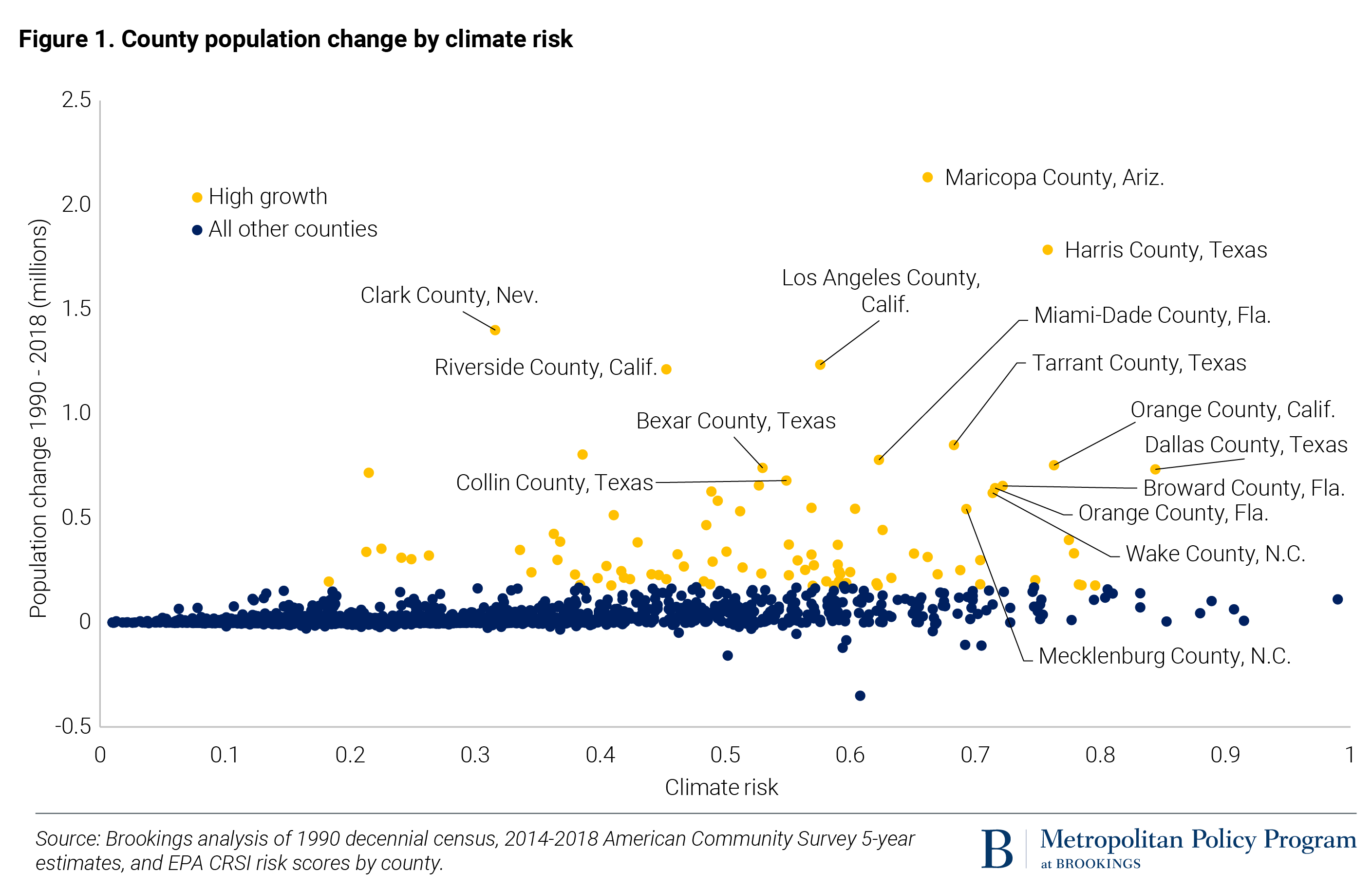

In 2017, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released estimates of U.S. county-level climate change risk (Appendix A). When contrasting population growth with climate risk, high-growth counties (largely the biggest metro areas in the Sun Belt and along the coasts) stand out as higher-risk (Figure 1). Just 88 out of 3,141 counties in the 50 states and Washington, D.C. account for half of U.S. population growth since 1990, and their median climate risk is 3.2 times higher than the risk of the remaining U.S. counties.

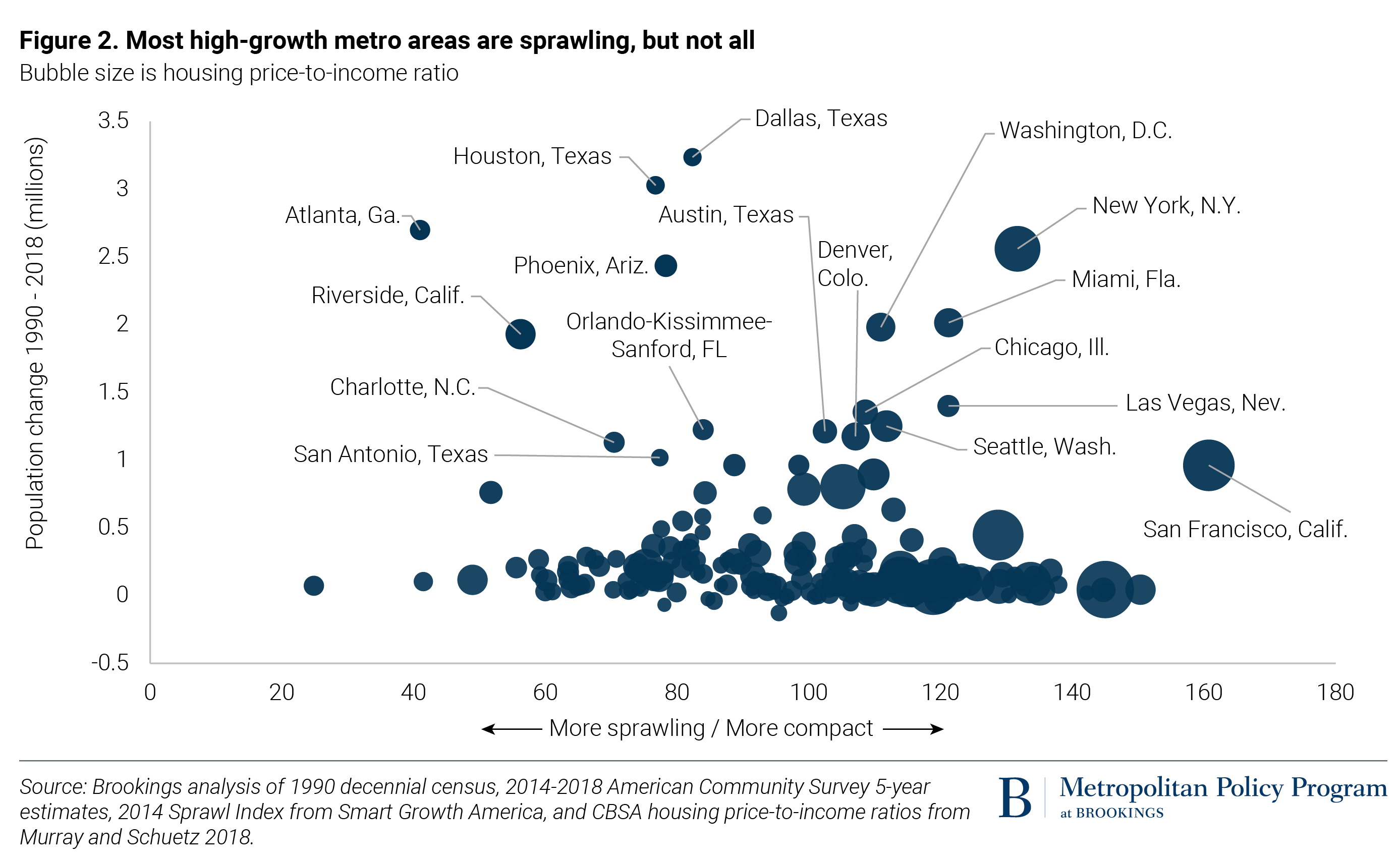

Sprawl has enabled many high-growth metro areas to control housing costs, because residents can “drive until they qualify” for a mortgage, as in the Sun Belt metro areas of Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, Atlanta, and Phoenix (Figure 2). However, in extremely high-cost, growing California metro areas, first-time and moderate-income homebuyers are driving past the urban fringe into areas most vulnerable to wildfires. Solving the puzzle of accommodating dense growth with attainable housing is critical work for building climate resilience.

The real estate ecosystem is streamlined to deliver sprawl—but demand is heading in the other direction.

There is a structural spatial mismatch between where we are building housing and new demand. Over the past several decades, land use and zoning regulations have favored the production of low-density, drivable suburban residential and commercial real estate. In high-growth metro areas, suburbanization continues because restrictive zoning ordinances have often made auto-oriented community design the only legal way to build and the easiest to finance using existing federal loan programs. Within many American cities, over 75% of residential land is zoned to exclude anything other than detached single-family homes—a number that climbs to 91% in many suburban communities.

We zone and build as though detached homes on big lots are everyone’s first and only choice—but they’re not. For the last 10 years, the number of college-educated young millennials living in dense, urban neighborhoods has increased by nearly one-third. This shift in demand toward density is likely to increase. A recent analysis combining results from a housing-preference survey conducted by the National Association of Realtors with household projections by tenure from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University estimated that by 2038, 70% of American households will prefer walkable communities—areas where only about one-fifth of households live today.

Our development patterns are making climate change worse.

The predominant patterns of U.S. home construction are environmentally and fiscally unsustainable. The low-density nature of single-family suburban developments requires their residents to travel long distances—7 miles per trip on average—by car for work and leisure, such that these residents emit an estimated 12.2% more carbon dioxide per capita than their urban counterparts. Between 1990 and 2017, U.S. greenhouse gas emissions rose 22% (despite an 18% increase in the overall fuel efficiency of the nation’s vehicles) due to the sheer volume of our travel.

Today, the federal policy that guides how we design and spend money on our roadways incentivizes car trips over walking, biking, or transit and further encourages auto-centric development. New highways, roads, and lanes induce more driving, which leads to more emissions and ultimately more congestion—creating a very costly feedback loop we can’t build our way out of.

By focusing on efficiency instead of resiliency, the real estate industry is missing a huge market.

Despite broad support for resiliency, industry and policymaker attention has been focused on improving energy efficiency in buildings and construction while still maintaining regulatory regimes and investment strategies that promote low-density development and automobile dependency. These actions largely ignore our growing exposure to a climate crisis that will put millions of residents and businesses at greater risk and set off a massive loss of assets and value too expensive for government-supported intervention or bailout.

Climate change is already escalating in cost to the built environment and worsening inequality. Sea level changes are only one dimension of this impact, which also includes droughts, high temperatures, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, and wildfires, among others. Miami Beach, the most at-risk city to sea level rise in the United States, stands to lose over 58% of its habitable land to flooding by 2060, causing 30.2% of its population to become internally displaced.

Why these trends matter

Mass suburbanization and the climate crisis it has helped create have placed particular harm on low-income households and people of color (most of whom are not low-income), while putting deep fiscal strains on every level of government.

On the first issue, housing costs take up a far larger share of income for low-income households than for more affluent ones. At the same time, the need to “drive until you qualify” pushes these households to spend increasing shares of their annual income on transportation (16% in 2014, up from 9% four years earlier). Without the expansion of affordable local- and regional-serving public transportation options and location-efficient housing—particularly in high-growth areas—lower-income households are forced into lower-priced housing stock at the urban fringe where long, unpredictable travel times and the costs and risks of automobile dependency add further strain.

While the climate crisis will ultimately harm everyone, low-income households with the fewest resources to adapt are suffering the fallout first. Low-income Americans—the majority of which are renters—are already disproportionately experiencing the effects of climate change and extreme weather events. Our current system prices some environmental risk into housing costs, so low-income residents naturally find their way into cheaper, riskier housing. For example, lower-cost housing is often located in flood zones, where land is less expensive, structures are more vulnerable to sea rise, and there isn’t enough infrastructure in place to protect buildings from flooding. Following Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Florence, 3.7 million Americans applied for Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) assistance; slightly more than half (51.4%) of applicants reported annual incomes of less than $30,000, while 23% reported annual incomes of less than $15,000. This reactive disaster response does not get out in front of the challenge of protecting low-income households from global climate forces.

On the second issue of fiscal strain, our sprawling patterns of development are coming at a very high cost—for everyone. The federal government spends or commits over $450 billion annually on real estate through direct expenditures and tax and loan commitments, with a majority of those funds directed to single-family homeownership in auto-oriented, suburban communities. And in transportation spending, auto-oriented development patterns (by definition and design) require more roadways and other infrastructure overall per capita—the construction, operation, and maintenance of which increases the local fiscal burden, hampering both the financial flexibility and overall competitiveness of sprawling communities.

All this should serve as an immediate call to action for the real estate industry, lenders, regulators, and community innovators to produce far more attainable housing, while dedicating robust resources to retrofit and fortify existing neighborhoods before internal climate migration and economic disruptions escalate further. This will require reimagining the industry’s future into one that yields greater fiscal, social, and environmental outcomes for more people and places.

The authors thank DW Rowlands for invaluable assistance in preparing Figure 1, Vicki Fanibi for her assistance in researching this piece, and Jenny Schuetz and Joseph W. Kane for invaluable feedback in shaping this piece.