Editor’s Note: For more info on content related to Community Ownership of Real Estate, please visit our page here.

The types and distribution of household structures in the United States have been evolving for decades. Consequently, we are now at a tipping point where our households and our housing inventory have become a round peg struggling to fit in a square hole.

Recent media coverage has presented these changes—such record numbers of adult children living with their parents—as the result of the pressures and preferences of the millennial generation. However, the decline of two-parent households with children and the rise of other family structures began with the coming of age of the first baby boomers in the second half of the 1960s, and continues today as that generation retires and seeks new living options.

These changes in the organization of American households have fundamental implications for the real estate industry and policymakers. As households change, so too must industry and public sector leaders by providing a broader range of housing choices that meets new demands—and creates more affordable, stable, and diverse communities in the process.

The trends

Over the past few decades, several significant demographic shifts have changed how and where Americans live. But the nation’s housing supply hasn’t kept up with demand.

The so-called “nuclear family” is no longer the dominant household structure.

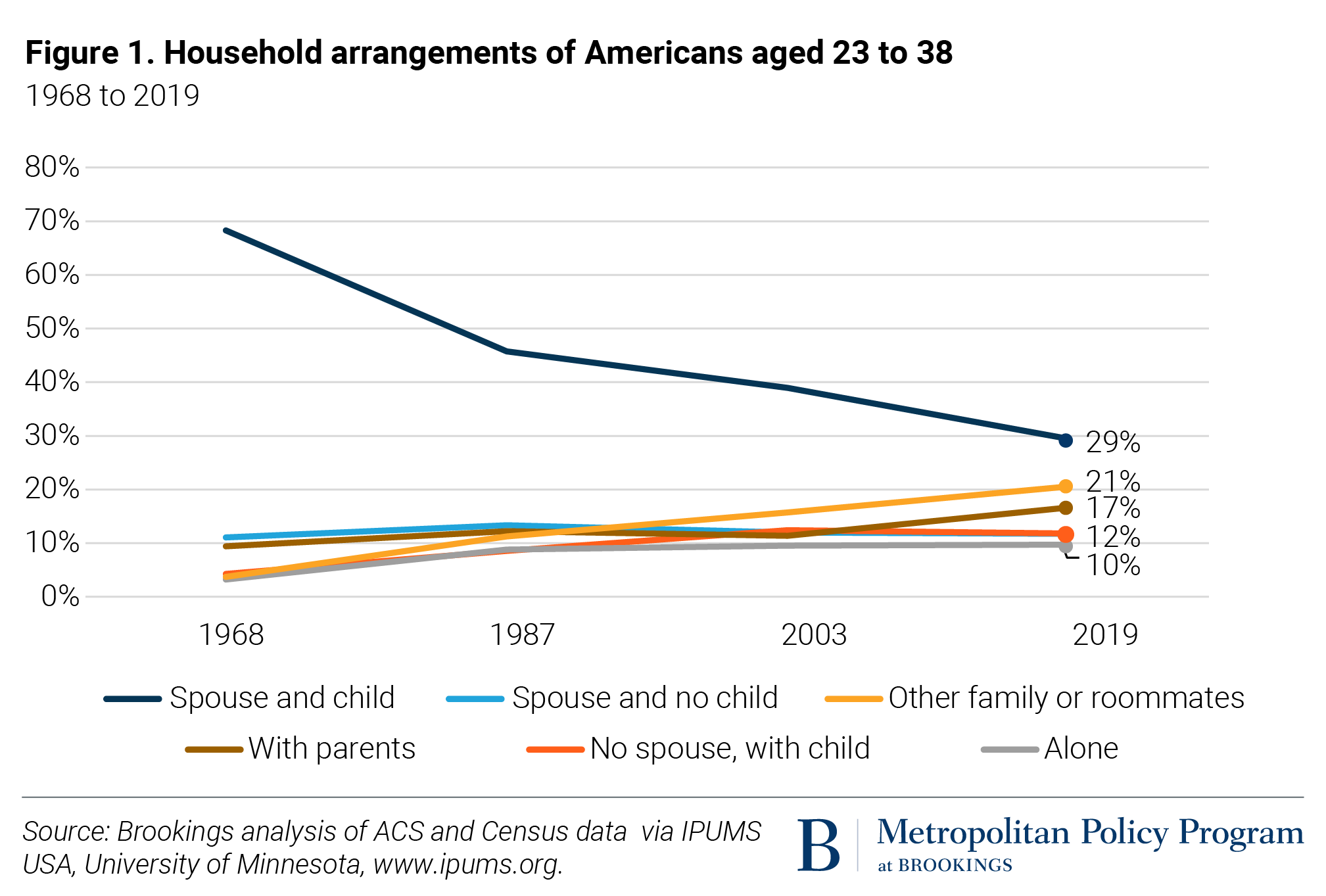

American family life is changing. Marriage rates have been steadily declining since 1980, and in 2018, the nationwide fertility rate hit an all-time low of 1.73 births per woman. As a result, household structures have shifted dramatically. In 1968, married couples with at least one child comprised nearly 70% percent of all households; by 2018, that share had fallen to less than 30%. At the same time, fewer than half of U.S. children are growing up in households led by two married parents in their first marriage. Single-parent households are now 12% of the total, up from only about 5% in the late 1960s.

Multigenerational and mixed family households have become more common, as Americans are increasingly “doubling up” to reduce housing costs.

While the prevalence of the nuclear family may be shrinking, the size of the average U.S. household is actually trending upward for the first time in over a century. From 1968 to 1987, the share of young people ages 23 to 38 living alone tripled, then plateaued at 10%. Meanwhile, the number of people in this age bracket living with siblings or other family members (i.e., not a spouse, children, or parents) or with nonrelated individuals grew steadily, rising from 5% to 21% of all households by 2019. One of the most significant recent trends has been the rising share of young adults moving back home: From 2000 to 2017, the share of nonmarried young adults living with their parents almost doubled, increasing from 12% to 22% due to high housing costs, tight credit, student debt, and other factors.

Our aging population is aging in place.

With the youngest baby boomers now 56 years old, the American population is aging rapidly. Americans over age 65 make up 16.2% of the total U.S. population, up from 11.5% in 1980. These numbers will continue to rise, such that households headed by someone over age 65 will comprise 34% of all households by 2038, up from 26% in 2018. Moreover, more than three in four Americans over age 50 express a preference for aging in place, citing affordability concerns and satisfaction with their current neighborhoods. The impacts of COVID-19 on care facilities may very well accelerate that trend.

Housing production across U.S. metropolitan areas hasn’t kept up with changing demand.

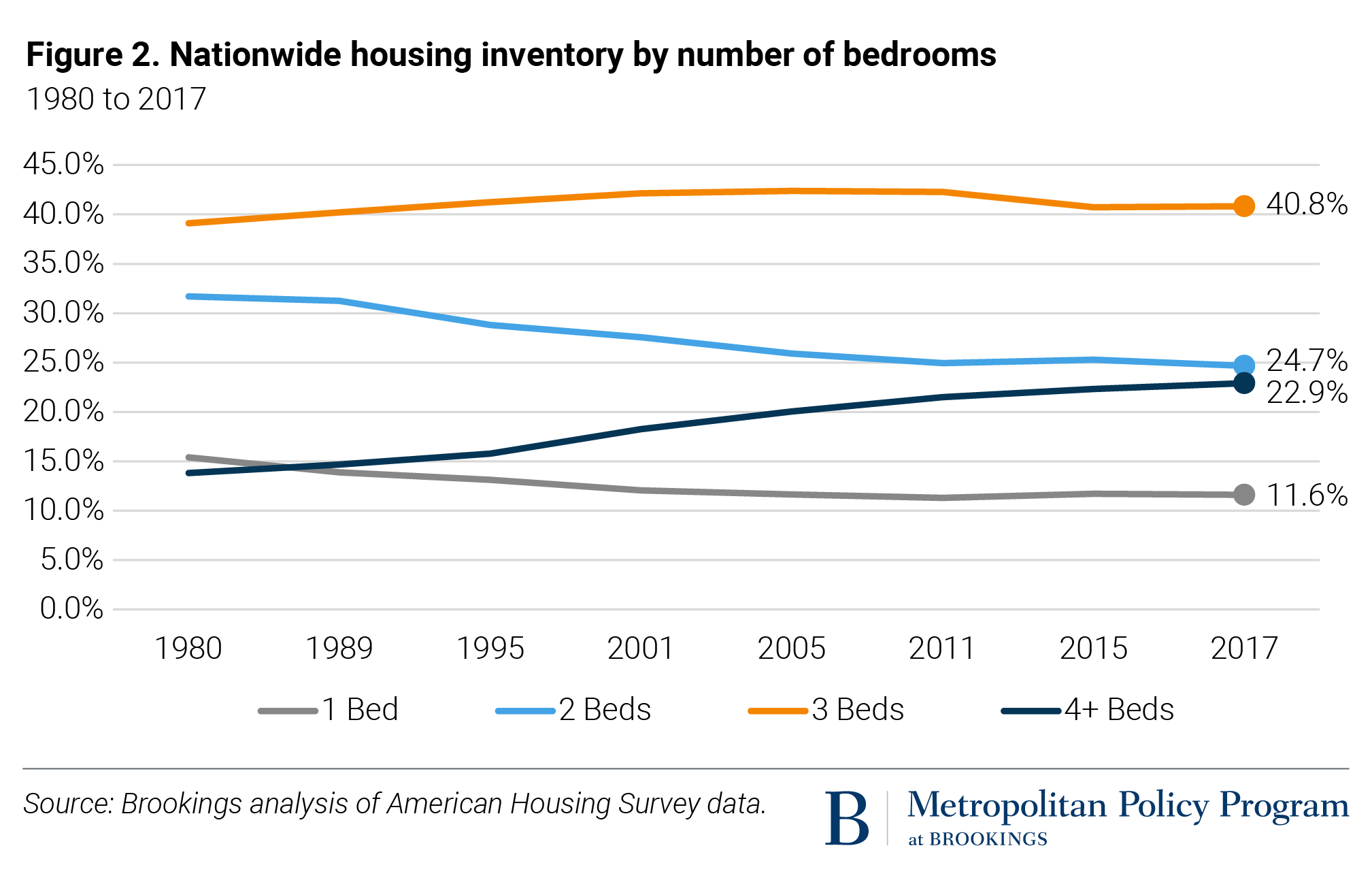

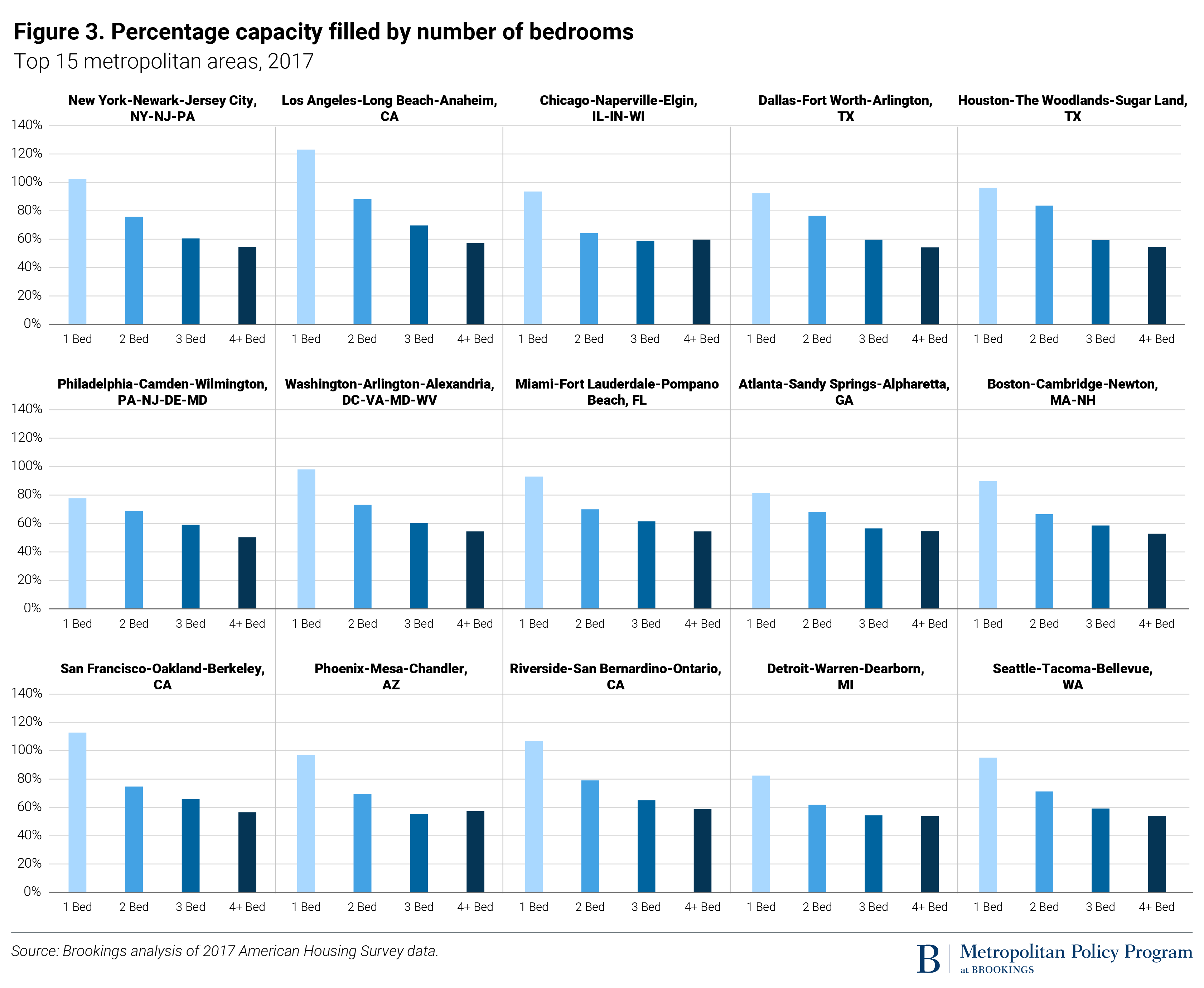

The decline of nuclear families and the rise of multigenerational or group living arrangements and aging in place are deflating demand for new single-family homes. Yet, the real estate industry—operating under restrictive zoning compacts—is still catering to the traditional nuclear family household by continuing to systematically undersupply small units (particularly one-bedroom units) in favor of constructing large single-family homes. Nationwide, the very largest houses (four or more bedrooms) have grown as a share of inventory while all smaller configurations have stagnated or declined (Figure 2).

The trends are particularly stark in the nation’s largest metro areas. Since 2013, units with four or more bedrooms have comprised almost half of housing inventory growth on average across the 15 biggest regions, while one-bedroom units have accounted for just 16.7% of such growth (Figure 3). Households in these high-cost, high-growth areas need smaller units. Based on HUD’s housing unit capacity standard of 1.5 people per bedroom, in all 15 of these metro areas, one-bedroom apartments are within 20% of full capacity on average, while they are over capacity in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Riverside, Calif. Meanwhile, units with four or more bedrooms in these areas are at just 55% capacity on average. This means that bedrooms in big houses are sitting empty while households wedge themselves into the smaller units that they can find—a fundamental mismatch between the inventory we have and what households need.

Why these trends matter

Changing demographic and household trends warrant transformative shifts in how the real estate industry approaches the supply of new housing. The industry’s response to these trends will have broad implications on housing choice and mobility for both younger and older generations.

Today’s under-40 population is a major driver of housing demand, with different needs and preferences than their predecessors. Millennials—those between the ages of 24 and 39 in 2020—are a market-shaping demographic simply by virtue of the fact that they are the largest generation by population. But for the credit-strapped, newly graduated young adult, buying a single-family “starter” home is no longer a financial possibility (nor always an aspiration, for that matter). Even for millennials that can afford to purchase a single-family home, homebuying is likely a bad investment, since the current supply of single-family homes does not match the desires nor the arrangements of millennial households.

All this means that while young people battle over the few available homes that suit their needs and preferences, older adults will be unable to sell their homes to the emerging generation of would-be homeowners. Even putting aside the generational mismatch in preferences and geographic location, the basic math does not bode well for the housing market: Seniors exiting the market will greatly outnumber young homebuyers, leaving 15 to 18 million surplus homes on the market. Most of the homes left will be large-lot, multi-bedroom homes—precisely the type of housing stock that markets in major metropolitan areas continue to oversupply.

Moreover, in predominantly catering to the traditional nuclear family, the real estate industry is continuing to serve the interests of white households over Black and brown households, for whom the suburban single-family home is often more a symbol of profound exclusion than something attainable. Homeownership among Black and Latino or Hispanic households significantly trails that of white households, and people of color are far more likely to be first-time as opposed to repeat homebuyers than white people. In part, this is because a mass of housing inventory weighted against starter homes disproportionately favors households with higher concentrations of generational wealth to pay bigger down payments. Over 6 million Black and brown millennials would be considered mortgage-ready if there was any attainable product for sale in prime locations.

In short, the business-as-usual approach to homebuilding has a wide range of negative impacts, demanding that real estate professionals and policymakers embrace a new framework and vision focused on providing greater housing options both through retrofits to existing priority neighborhoods and through new developments. This framework must include regulatory, finance, and design tools that create more—and more affordable—choices for people of all ages, races, and family sizes and mixes.

The authors thank William H. Frey for his helpful review of this piece.