Dwight’s Glasses

A few years back, I was delighted to see my godson wearing glasses. It makes me feel better to know others are aging too. Judge me if you like. “Don’t feel too bad, Dwight,” I said with faux sympathy. “It happens to all of us in the end.” Dwight laughed. “Oh no,” he said, “these are clear lenses. I just do more business when I’m wearing them.” Dwight sells cars for a living. I was confused. How does wearing unnecessary glasses help him sell more cars? “White people especially are just more relaxed around me when I wear them,” he explained.

Dwight is six foot five. He is also Black. It turns out that this is a common tactic for defusing white fear of Black masculinity. When I mentioned Dwight’s story in a focus group of Black men, two of them took off their glasses, explaining, “Yeah, me too.” In fact, I have yet to find a Black American who is unaware of it, but very few white people who are. Defense attorneys certainly know about it, often asking their Black clients to put on glasses. They call it the “nerd defense.” One study found that glasses generated a more favorable perception of Black male defendants but made no difference for white defendants.

Dwight’s statement was one of those moments when your whole view of the world shifts on its axis. It was like that evening over dinner when I asked him if he often gets stopped by the police. “No, not really,” he said. Then, “maybe every few months?” And after a pause: “I was handcuffed by them a little while back though. Mistaken identity, they said.” At times like this, I realize that I do not have the faintest idea what it is like to be Black in America, and specifically to be a Black man. And so, an advisory warning: as a British-born white guy, my perspective on American racism will need to be discounted appropriately. For what it is worth, however, I am convinced that one of the principal impediments to equity in the U.S. today is the combination of racism and sexism faced by Black men.

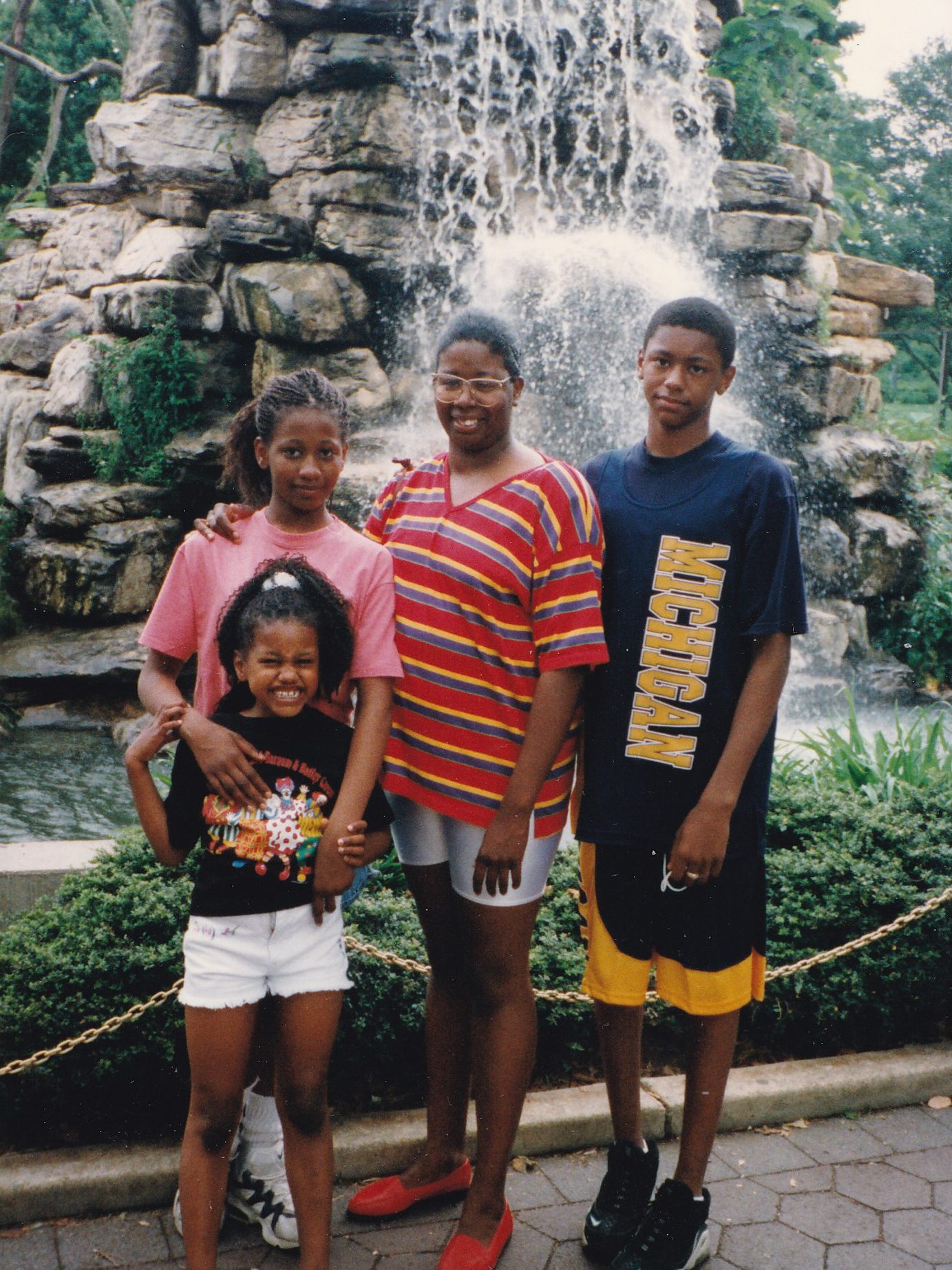

Like many Black men in America, Dwight has had a tough journey. He grew up in one of the toughest neighborhoods of West Baltimore. He cannot remember his father, who died when Dwight was young. Given the profound, specific challenges faced by Black men in almost every aspect of American life, from criminal justice to education and employment, putting on a pair of clear tortoiseshell frames may seem trivial. Certainly, Dwight is nonchalant about it. “It is what it is,” he says. But I think it says almost everything. Knowing they are perceived as a threat, Black men resort to unneeded eyewear, not to see us, but so that we might see them.

Reverse sexism

In the late 1980s and 1990s, a breakthrough occurred in the study of inequality and discrimination with the development of “intersectionality.” Pioneered by Kimberlé Crenshaw, this framework was initially grounded in Black feminism, but it provides a way to examine how different forms of oppression operate in combination. Rather than seeing inequality in binary terms, such as male/female, Black/white, rich/poor, or gay/straight, Crenshaw insists on the “complexities of compoundedness.”

The power of intersectional thinking derives from its inescapable pluralism. Each of us are “multiply” identified. You may be a Black heterosexual Jewish socialist lawyer; I may be a white gay atheist libertarian coal miner. This insistence on plural identities echoes centuries of progressive liberal thought, from John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor Mill in the nineteenth century to Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum in the twenty-first.

Black men face different intersections of disadvantage, many of which may be more acute than those faced by Black women.

Crenshaw centers her work on Black women, but the framework can be used more broadly, and the position of any particular group is not fixed in relation to that of another group. As my colleague Tiffany N. Ford, a public health scholar, writes of intersectional approaches, “Social categories are contextual. Fundamental traits are not fixed, but rather constantly changing over time.” What it means to be queer, or Black, or male is not fixed in relation to what it means to be straight, or white, or female. Patterns of advantage and disadvantage are not set in stone. So anti-Black gendered racism hurts Black men and Black women, but not in the same way. Gender is racialized, and race is gendered, in different ways, in different places, and at different times. Consider the conservative archetype of the “welfare queen,” a gendered lens through which to pathologize Black women receiving public assistance.

Black men face different intersections of disadvantage, many of which may be more acute than those faced by Black women. As Tommy Curry, chair of Africana Philosophy and Black Male Studies at the University of Edinburgh, writes, “In liberal arts fields it is assumed that because Black and brown men’s gender is masculine, there is an innate advantage they have over all women and are patriarchal.” But Curry argues that the opposite is true. In The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood, he argues that Black males in the U.S. are “oppressed racialized men.” Curry urges the creation of a new scholarly field of Black male studies, on the grounds that the accounts offered by existing feminist and intersectional scholars are missing the mark when it comes to the specific forms of gendered racism faced by Black men.

But the challenge is not just in academia. Efforts to focus on the specific challenges of Black boys and men are often viewed with suspicion, as distractions from the challenges of Black women or people of other races and ethnicities. I want to be clear about my own position. I believe that the deepest American prejudices are rooted in anti-Black racism, specifically toward the people that legal scholar Sheryll Cashin calls “descendants,” African Americans who “descend from the long legacy of slavery.” For this reason, among others, I don’t much like the term people of color, or the idea that the main dividing line is between white Americans and everybody else. I understand the need to build coalitions. I also understand the desire not to appear to be downplaying racism for other groups. But the idea that all people who are not white are in a similar position to that of Black Americans is both morally offensive and empirically wrong. Anti-Black racism is the main challenge, and it is at least as great for Black men as for Black women.

Hard facts on Black men

Dwight spent the first 11 years of his life living in Rosemont, West Baltimore. Or as the U.S. Census Bureau would put it, Tract 24510160700. It was a Black neighborhood then. It is a Black neighborhood now. By Baltimore standards, the outcomes for children from Rosemont are not too bad. But this is not the same as saying that they are good; in terms of adult outcomes, Baltimore is one of the worst places in America to grow up as a boy. Among the boys born around 1980 into low-income families (Dwight’s cohort) in Rosemont, one in seven (16%) were in prison on April 1, 2010. To be clear, not that they had been to prison by April 1, but that they were in prison on that date. In fact, more of these boys became prisoners than became husbands: The marriage rate for this cohort by their mid-30s was just 11%. One in three were still living in the neighborhood, which means their children will likely go to the local Belmont elementary school. All of Belmont’s students are Black. To say that outcomes from the school are poor would be an understatement. At the elementary school my children attended in Bethesda, 82% of the students cleared Maryland’s proficiency standards in math in 2019. Statewide, the proportion was 58%. At Belmont, it was 1%. The scale of our failure here is almost incomprehensible.

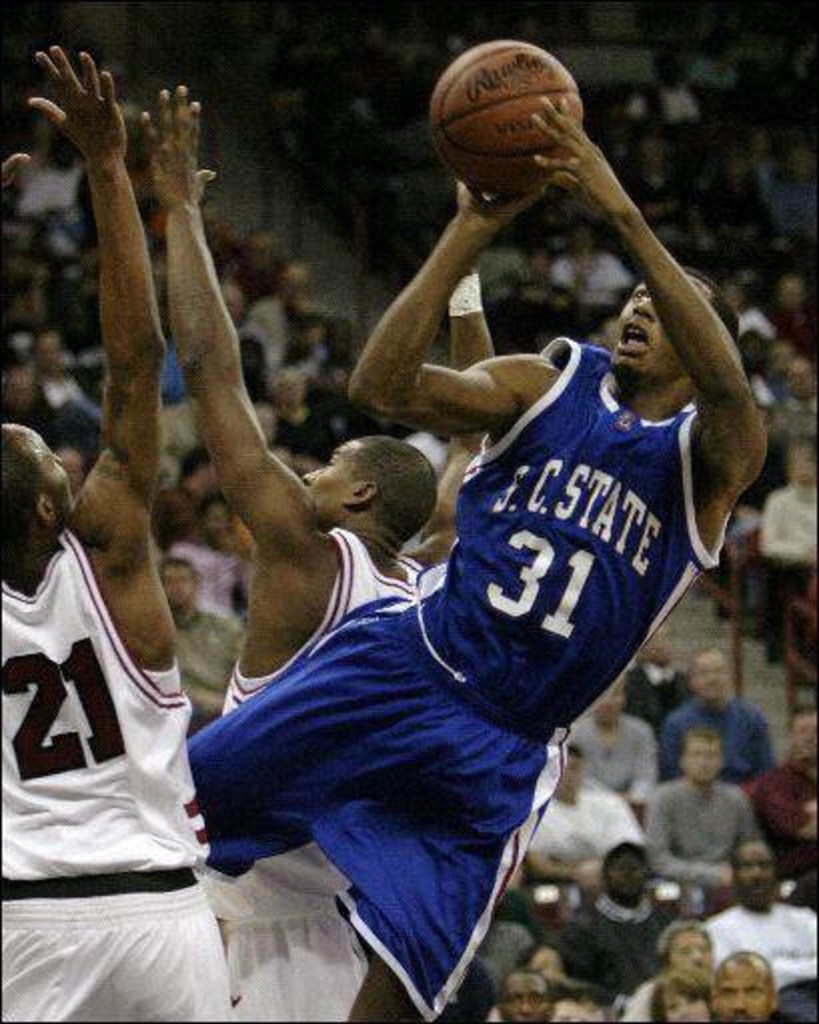

When Dwight was 11, stray gunshots were fired through his bedroom window. Working two full-time jobs, his mother managed to move the family out of the neighborhood, and he won an athletic scholarship to a private Catholic school and then to two colleges. As an upwardly mobile, well-educated, economically successful Black man, Dwight is an exception that proves the rule. Raj Chetty and his team at opportunity Insights have crunched the numbers on 20 million Americans born around 1980, to look closely at intergenerational patterns of poverty and mobility. They find that Black men are much less likely than white men to rise up the income ladder, while Black and white women raised by poor parents have similar rates of upward intergenerational mobility. Chetty and his team conclude that the overall Black– white intergenerational mobility gap “is entirely driven by differences in men’s, not women’s, outcomes.”

But of course, Black women also suffer from the poor economic outcomes of Black men, not least in terms of household income. “Black women continue to have substantially lower levels of household income than white women, both because they are less likely to be married and because Black men earn less than white men,” write Chetty and his team. In similar research, Scott Winship, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and I find that marriage rates are a small part of the story. The main problem is the low incomes of Black men, especially of those raised in poverty. This means that despite some impressive progress made by Black women, their children are still much more likely to grow up poor, reinforcing intergenerational inequality. Breaking the cycle of poverty for Black Americans will require a transformation in the economic outcomes for Black men.

Chetty has provided some sharp new statistics, but the insight is hardly new. “Many of those who escape do so for one generation only,” wrote Daniel Patrick Moynihan in his 1965 report on the Black family. “As things now are, their children may have to run the gauntlet all over again.” One way to avoid running the gauntlet again is by getting a good education. But as the figures for Belmont elementary dramatize, quality schools and colleges remain less accessible to Black Americans.

And the boys and men are at a particular disadvantage here. As Jerlando F. L. Jackson and James L. Moore write in a special issue of the Teachers College Record, “Throughout the educational pipeline— elementary, secondary, and postsecondary— . . . African American males lag behind both their African American female and white male counterparts.”

Black women are seizing educational opportunities long denied to them, and on some fronts they have overtaken white men. Black girls are more likely than white boys to have graduated from high school; young Black women aged 18 to 24 are more likely than young white men to be enrolled in college; and more Black women aged 25 to 29 hold more postgraduate degrees than white men of the same age.19 The gaps here are modest, but they illustrate the important educational gains made by Black women in recent years. The gender gap in education between Black women and Black men is much wider than the one between white women and white men, as figure 1 shows. For every Black man getting a college degree, at all levels, there are two Black women.

Black men face particularly acute challenges in the U.S. But there are similar patterns in other countries. In the UK, for example, the gender gap in education is most pronounced among Black students, with Black boys lagging Black girls in all subjects at all ages. (It is worth noting here, however, that the group doing worst at British schools are white boys from lower-income backgrounds.)

Black men therefore enter the world of work with fewer educational credentials than almost any other demographic group. Then they face a greater risk of discrimination in many parts of the labor market, as well as higher rates of incarceration. As a result, there are more Black women than Black men in the labor force, in contrast to every other racial or ethnic group. This is not just an issue of poverty. As Chetty reports, Black men raised in relatively affluent families have lower employment rates than white men raised in poverty.

Among the boys born around 1980 into low-income families in Rosemont, one in seven were in prison on April 1, 2010.

Those Black men who are in work receive some of the lowest wages; the weekly wage of the typical Black male worker in 1979 was $757 (in today’s dollars). Today it is $830. That is a gain of just 10%.

Again, it is important to look at race and gender together here. White women have seen the most dramatic economic gains in recent decades, as figure 2 shows. In 1979, white and Black women earned the same. Now Black women earn 21% less. White women caught up with Black men by the 1990s and have had faster-rising earnings ever since. Black men now earn 14% less than white women (and 33% less than white men).

Gender gaps in the labor market are narrowing while race gaps widen. The overall gender pay disparity is closing because the wages of women, especially white women, are rising rapidly. Meanwhile the Black–white pay gap is widening, as Black workers, especially Black men, see painfully slow growth in wages. Given these trends, it should not be a surprise to learn that Black women are more likely than Black men to be the main family breadwinner, again in contrast to every other racial group.

In terms of upward mobility, employment, wages, and breadwinning status, the status of Black men is starkly different from that of white men, and on most measures also lagging behind Black women.

None of this is to suggest that Black women have somehow sprung free of racism or sexism or achieved anything close to equality. Black women face a different combination of disadvantages than Black men; there is some evidence, for example, that Black women experience greater discrimination when they become mothers. They face gendered racism too, albeit of a different kind.

But there is a particular pain point for Black boys and men, not in spite of their gender, but because of it. A summary of Chetty’s research in the New York Times concludes that “there is something unique about the obstacles black males face.” A 2022 study by a team of researchers from the Urban Institute and Child Trends sharpens the point. Using a microsimulation model, they estimated the effect of structural. Specifically, they “asked what would happen to the lifetime earnings of Black and Hispanic people if, from birth to adulthood, they experienced society in the same way white people do?” (Note that the simulation does not change circumstances at birth). One of the main outcome measures was lifetime earnings, and these improved for Black and Hispanic men and women. But differences in the scale of the change were huge, as figure 3 shows. Black men would see a “transformative” change in earnings if structural racism were “removed,” with their lifetime earnings jumping from 39 cents for every dollar earned by white men to 91 cents. For Black women, the increase is from 75 cents for every dollar earned by white women to 82 cents. The clear implication here is that on this measure at least, Black men suffer by far the most from structural racism.

This is one reason why President Obama launched his 2014 initiative, My Brother’s Keeper, which lives on as the MBK Alliance in the Obama Foundation. The Alliance has just awarded grants to four “MBK Model Communities” which are seeking to “achieve systems-level impact in the lives of boys and young men of color.” This focus on boys and men has been criticized, for example, by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, for drawing attention away from the challenges faced by Black women. But it seems right to me, given both the disparities described as well as the general lack of institutional investment in issues facing boys and men. There are, after all, many organizations, both public and private, focused on women, many of which also address some of the challenges faced by Black women. In recent years, some foundations and think tanks have also paid more attention to Black men. But the response still looks tepid given what Camille Busette describes as an “appalling crisis.” We need, she says, nothing less than a “New Deal for Black Men.”

The threat stereotype

Many Black men, including Dwight’s former neighbors in Baltimore, end up in what Ta-Nehisi Coates calls the “Gray Wastes” of the American prison system. One in four Black men born since the late 1970s have been in prison by their mid-30s. Among those who dropped out of high school, it is seven out of ten. These men hit young adulthood just as the imprisonment boom began in the 1980s and 1990s as part of the bipartisan war on drugs.

The problem starts with the perception that Black men are dangerous. Black men are “uniquely stigmatized,” according to studies of implicit bias conducted by political scientists Ismail White and Corrine McConnaughy. One in three white Americans rank “many or almost all” Black men as “violent,” compared to just one in ten who say the same of white men. According to McConnaughy and White, “The gender modifier does unique work in accessing negative notions of black men.” In other words, Black men are discriminated against because they are men. It hardly needs saying that this is an old problem. “Keeping the Negro ‘in his place’ can be translated as keeping the Negro male in his place,” Moynihan noted in 1965. “The female was not a threat to anyone.”

These perceptions constrain the lives of Black men in very specific ways. My colleague Rashawn Ray, a sociologist, shows for example that middle-class Black men are less likely to be physically active in neighborhoods that are mostly white. Why? Because Black men are trying to avoid being seen as a threat. “Black men have a different social reality from their Black female counterparts,” he writes. “The perceptions of others influence Black men’s social interactions with co-workers and neighbors [and] structure a unique form of relative deprivation. In this regard, the intersectionality framework becomes useful for illuminating Black men’s multiplicities and vulnerabilities.”

This is intersectionality as a matter of life and death. On February 23, 2020, Ahmaud Arbery was shot dead while out for a run in his neighborhood. His killers were Gregory McMichael, a former police officer, and McMichael’s son, Travis. Despite irrefutable evidence, they were not arrested for two months. Ibram X. Kendi, a scholar from American University, wrote of his own experience of running. “They don’t need to figure out who I am. All they see is what I am. A Black male. And what I am pronounces who I am. A criminal. The embodiment of danger. The producer of fear.”

Seen as more threatening, Black men are more likely to be stopped by the police, more likely to be frisked, more likely to be arrested, and more likely to be convicted. The wars on drugs and crime became in effect a war on Black men, who are more than three times as likely to be arrested for a drug crime than white men (though no more likely to use drugs) and nine times more likely to end up in a state prison as a result of a drug offense. For Black men, even more than for men in general, masculinity is a double-edged sword. Black masculinity was seen as “toxic” long before the term was applied more broadly, as shown by the use of terms like superpredator and wolf pack to describe Black male offenders.

One of the most striking aspects of anti-Black gendered racism, as directed against boys and men, is its physicality. As Ta-Nehisi Coates has written, this is a history of bodily theft and destruction, of “carriage whips, tongs, iron pokers, handsaws, stones, paperweights or whatever might be handy to break the Black body, the Black family, the Black community, the Black nation.” And now, of guns too. In July 2016, three Black men were shot by police officers on three successive days in three different cities: Delrawn Small in Brooklyn, New York; Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana; and Philando Castile in Saint Paul, Minnesota. On the third day, a close colleague came to my office, ostensibly to talk about a work project. She is a Black mother and was in tears within a few minutes, worried sick about her boys, and perplexed by the way all the people around her were managing to go about their daily tasks as if there was nothing wrong. Until she walked through my door, I had been one of those people, too.

One of the reasons Black men are less likely to be in the workplace is simply that they are so much more likely to be in jail. And even when they are released, their chances of finding work are massively reduced. This is not just because they have a criminal record—it is because employers are more likely to view Black men as criminals anyway. One striking study showed that a Black man without a criminal record is less likely to be hired than a similarly qualified white man with a criminal record. This is why reforms to “Ban the Box” (i.e., remove the requirement to declare a criminal record when applying for a job) do not seem to improve the chances of Black men being hired. As Devah Pager writes, “effectively, the job market in America regards Black men who have never been criminals as though they were.”

One of the reasons Black men are less likely to be in the workplace is simply that they are so much more likely to be in jail.

The criminalization of Black men in America has resulted in millions of workless men and millions of fatherless families. But men struggling in the labor market often struggle in the marriage market too, leading to higher rates of single parenthood. President Barack Obama describes the “hole” in his heart left by the absence of his father. Many Black men suffer from “post-traumatic missing daddy disorder,” according to Jawanza Kunjufu, author of Raising Black Boys. Before their 14th birthday, one in four Black children see a parent go to jail or prison, usually their father. Daniel Beaty, a writer, actor, and poet, recalls a childhood game he played until he was 3. When Beaty’s father knocked at his bedroom door in the morning, Beaty would pretend to be asleep, before jumping gleefully up into his father’s arms. Until the morning his father did not knock, because he was in prison. Three decades later, Beaty performed his poem “Knock, Knock,” which includes the following lines:

Twenty-five years later I write these words for the little boy in me who still awaits his papa’s knock. . . .

Papa, come home cause I miss you

I miss you waking me up in the morning and telling me you love me.

Papa, come home, because there are things that I don’t know and I thought maybe you could teach me:

how to shave, how to dribble a ball, how to talk to a lady, how to walk like a man.

I have more to say about the importance of fathers in “Of Boys and Men.” But for now, I will note that Black boys seem to benefit even more than others from engaged fatherhood, and that on many measures, Black fathers are more engaged than fathers of other races, especially when they are not married to or living with the mother.

Stressed Black families

Black women have always played a more important economic role in the family, especially compared to white women. Even today, inequality shapes racial differences in family life. Half of Black women raising children are doing so without a husband or cohabiting partner, in stark contrast to women of other racial groups, especially whites. Black mothers are three times as likely as white mothers to be single parents (52% v. 16%), and half as likely to be living with a spouse (41% v. 78%). Most births to Black women take place outside marriage (around 70%), compared to about half the births to Hispanic women, and 28% of those to white women.

A comprehensive study of marital trends by Kelly Raley, Megan Sweeney, and Danielle Wondra concludes that “compared to both white and Hispanic women, Black women marry later in life, are less likely to marry at all, and have higher rates of marital instability.” Black women in their early 40s are five times as likely as white women of the same age to have never married (34% v. 7%). Black marriage has been undermined by anti-Black racism, including by the specific challenges faced by Black men. In his sociological classic The Truly Disadvantaged, published in 1990, William Julius Wilson argued that dire economic conditions create a smaller pool of “marriageable men,” so fewer couples tie the knot. I have always been uncomfortable with this argument, because male “marriageability” is based on stereotypical assumptions. To be marriageable, a man has to be a breadwinner. How outdated and sexist! The trouble is that most people, including most Black people, agree with Wilson. Breadwinning potential is highly prized in a potential mate: 84% of Black Americans say that in order to be a good husband or partner, it is “very important” for a man to be “able to provide for their family financially,” compared to 67% of white respondents. But the gap is even wider when it comes to female providers: 52% of Black Americans say it is very important for women to be able to financially support their family, compared to just 27% of white Americans. Given the economic challenges facing Black women and men, this is not surprising. But while Black women are seeing some improvement in their educational and economic positions, and therefore their ability to fill the breadwinning role, Black men are falling way behind.

I hope it is clear that I am not arguing for somehow elevating Black men above Black women, even if that were possible, but just to help them to keep up. More needs to be done to clear the obstacles in the path of Black women. But even more now needs to be done for Black men. This is not a zero-sum game, and it is vitally important that it is not framed as such, as Moynihan did in a letter to President Johnson in 1965. “Men must have jobs. We must not rest until every able-bodied Negro male is working,” he wrote, before adding, fatally, “even if we have to displace some females.” of course, Moynihan was writing more than half a century ago. He was also a white man and an establishment figure. But we should not just dismiss the comment. Even today, there is a fear that helping men means hindering women, whether by design or by happenstance. But it is not true. It is important to strive for equity in terms of gender, class, and race—as Heather McGhee argues in her book The Sum of Us. Raising men up does not mean holding women down, or “displacing” them. It means rising together.

Free men

On August 9, 2014, Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teenager, was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, part of the St. Louis metro area. The next day, August 10, Dr. Sean Joe arrived in the city. He had come to fill the post of professor of social development at Washington University. Joe was already planning to work on the issues confronting Black boys and men. Now, as the city reeled from Brown’s death and its aftermath, his work took on a new urgency. He created a new race and opportunity lab and an initiative, Homegrown STL, focused on improving the prospects of the 60,000 Black boys and men aged between 12 and 29 who lived in the area. Following Brown’s death, a commission of local leaders was charged by the governor of Missouri with the task of conducting “a wide-ranging, in-depth study of the underlying issues brought to light by the events in Ferguson.” In October 2015, the commission issued a hard-hitting report on the history and impact of racism in the city and provided almost 200 recommendations for reform.

But Sean Joe was disappointed. “The report talks about racial equity in general—but says nothing about Black boys and men specifically,” he told me. “We need to be able to talk confidently about the issues facing Black boys and men. This is what Michael Brown represented. It was not just the fact that he was Black that mattered—it was the fact that he was a Black male. People just don’t want to talk about that.” The report is indeed silent on gender. This is not an uncommon problem. Race equity is now on the agenda of many institutions and communities. But there is a real reluctance to focus on the particular challenges faced by Black boys and men. The fact that Black males are disadvantaged because of their gender doesn’t fit into the binary models of racism and sexism that many are comfortable with. Given the weight of evidence now available on the specific plight of Black men, this just won’t do.

“It was not just the fact that he was Black that mattered—it was the fact that he was a Black male. People just don’t want to talk about that.”

-Sean Joe, Founder, Homegrown STL

There are some signs of hope. In 2020, a rare piece of bipartisan legislation established the Commission on the Social Status of Black Men and Boys. This is a nineteen-member permanent commission within the United States Commission on Civil Rights, charged with investigating “potential civil rights violations affecting Black males” and “studying the disparities they experience in education, criminal justice, health, employment, fatherhood, mentorship and violence.” Modeled on a similar initiative in Florida, the Commission is required by law to report annually to Congress with policy recommendations and advice. There was some resistance to the Commission’s creation from congressional Democrats, again fearing, wrongly I think, that it would distract from women’s issues. As then-Senator Kamala Harris said, “It is time that we come to terms with the fact that America has never fully addressed the systemic racism that has existed in our country— particularly toward Black men and boys.” The gendered racism faced by Black boys and men is unique in its level of harm, and it is time to face it squarely. Many of the proposals I make later in this book have this goal in mind. After a long conversation about his own challenges, I asked Dwight what he most wanted for his three sons. “I just want them to be free, you know?” he said. “Free of the fear, free of just the crushing awareness of it all. Just free.”

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

This essay is adapted from a chapter of Richard Reeves’ recent book, Of Boys and Men, published by the Brookings Institution Press in September 2022.