Strong tenant protections and subsidies support Germany’s majority-renter housing market

Editor’s note: In case you missed it, watch an event held on April 21 discussing lessons from around the world related to policies to support stable, affordable rental housing.

Germany is one of the few developed nations with high rentership rates: More than half of all households rent their home. The German government has chosen to focus subsidies on renters rather than owner-occupiers. While renter households are typically younger and less affluent than homeowners, rentership is still widespread even among higher-income and higher-wealth groups. Strong renter protection is a key element of federal legislation and is playing an important role during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overview of rental housing and renter households

Germany: A nation of renters

After about 20% of Germany’s housing stock was destroyed in World War II, 12 million people were made homeless or displaced. The huge housing shortage had to be combated quickly and at low cost, leading to the birth of subsidized housing in the postwar period. Builders, such as not-for-profit and private housing companies, received federal subsidies to erect new housing and, in turn, had to rent out their units to low-income households at user cost. The effects of post-WWII housing policies are still felt today: Around 54% of Germany’s households rent their homes.

Rentership levels vary across the 16 federal states, but more households rent in the east (66%) than in the west (53%) of Germany. Renting is also much more common in the city-states of Berlin (83%) and Hamburg (76%) than in the states of Rhineland-Palatinate (42%) or Saarland (36%), largely reflecting regional rental price differences.

Almost 90% of rental units are in multifamily buildings, and they are mostly row houses; detached single-family homes are the minority. At the urban fringes in eastern Germany, Plattenbau—apartment blocks that often house a few dozen families—are still a common sight.

Renters are younger and more mobile in the labor market

Because renting is the predominant housing model in Germany, renter households are very diverse. Still, renting is more common for households with heads of foreign nationality (76%) than for those with a German passport (53%). Not surprising in light of its history, Germany does not collect information on residents’ race. Single-person households and single-parent households are most likely to live in rental accommodations, while couples with and without children mostly own their homes.

Renters are more often in younger and older age groups. Of those aged 25 to 34, 85% rent their homes (for ages 35 to 44, 71% rent), and of those age 75 and older, slightly more than half are renters. Homeownership rates peak in the remaining age groups. Because the high transaction costs associated with buying homes are a burden, especially for younger people (who also more often face labor mobility requirements), young households tend to remain renters for longer.

In terms of labor market status, there are more renters among white-collar private sector employees (55%) and blue-collar workers (60%) than among the self-employed (46%) and civil servants (44%). Unemployed residents are mostly renters (91%). Half of pensioners live in rental housing. Civil servants, by contrast, are employed by the government and benefit from better mortgage conditions due to their exceptional job safety. This could explain why only one-quarter of retired civil servants rent their homes.

Rentership is also strongly associated with having no school completion or vocational qualification. As soon as the household has obtained some qualification, homeownership rates increase sharply to levels above 50%. Those with a technical college degree are least likely to be renters (37%). This is in stark contrast to those with higher vocational training (over 50%), but is likely explained by the former’s earlier attainment of job security.

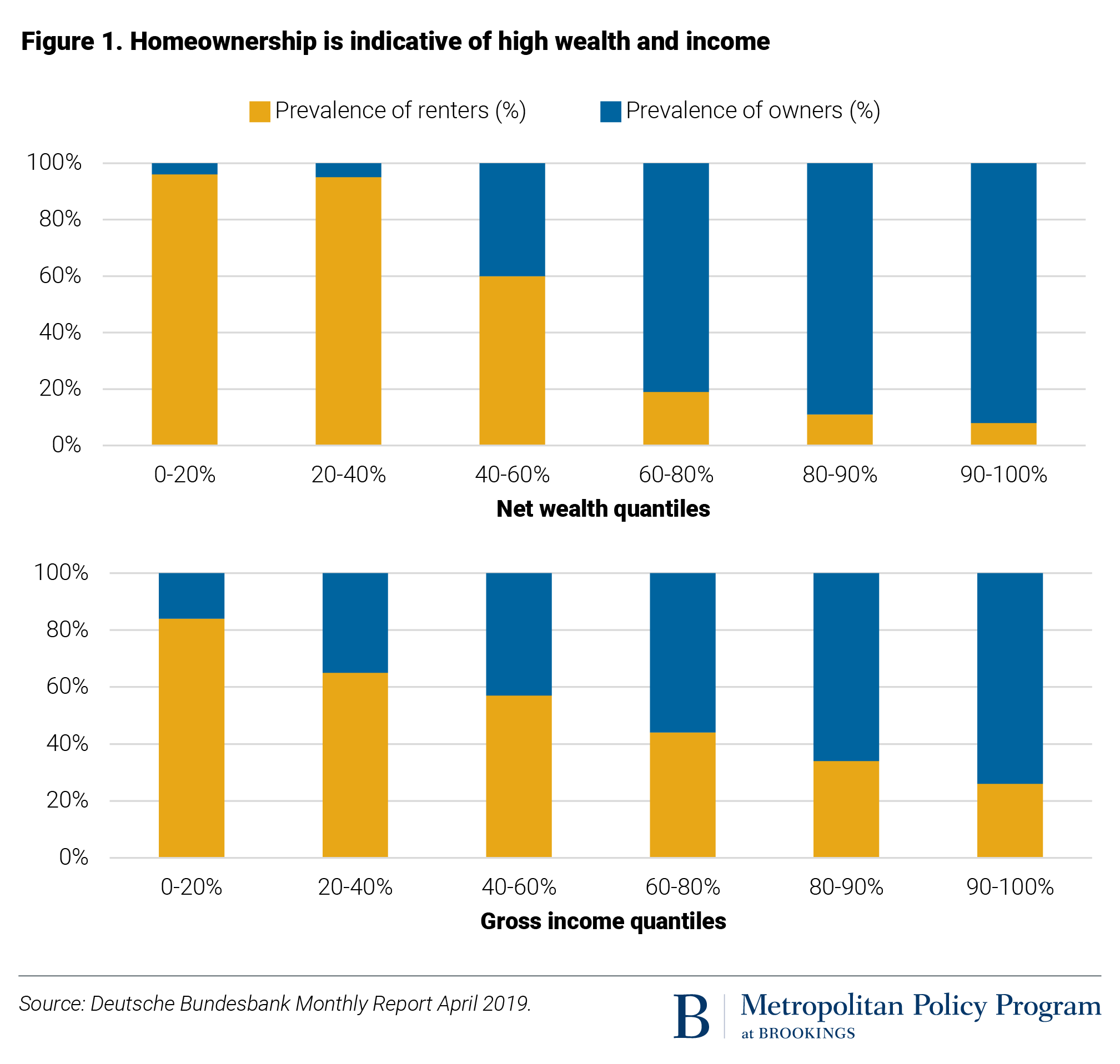

Renters are less affluent than owners

Homeownership is strongly correlated with net wealth and income (Figure 1). The median renter household has less net wealth (€10,400) than the typical owner household (€277,000), even if one adjusts owners’ household wealth for the value of the home. Homeowners’ housing wealth has increased strongly due to a recent housing boom.

Institutional and policy environment of rental housing

Homeownership is not heavily subsidized

Unlike most other developed countries, households that own homes are incentivized to rent out rather than occupy their homes for two reasons. First, mortgage interest is only deductible from one’s income taxes when the home is rented out. Second, as mentioned earlier, transaction costs for home purchases are high by international standards, making homebuying, let alone frequent moves, very costly. Research suggests that, if implemented, certain tax-related policy interventions aimed at raising the homeownership rate would primarily hurt those that remain renters.

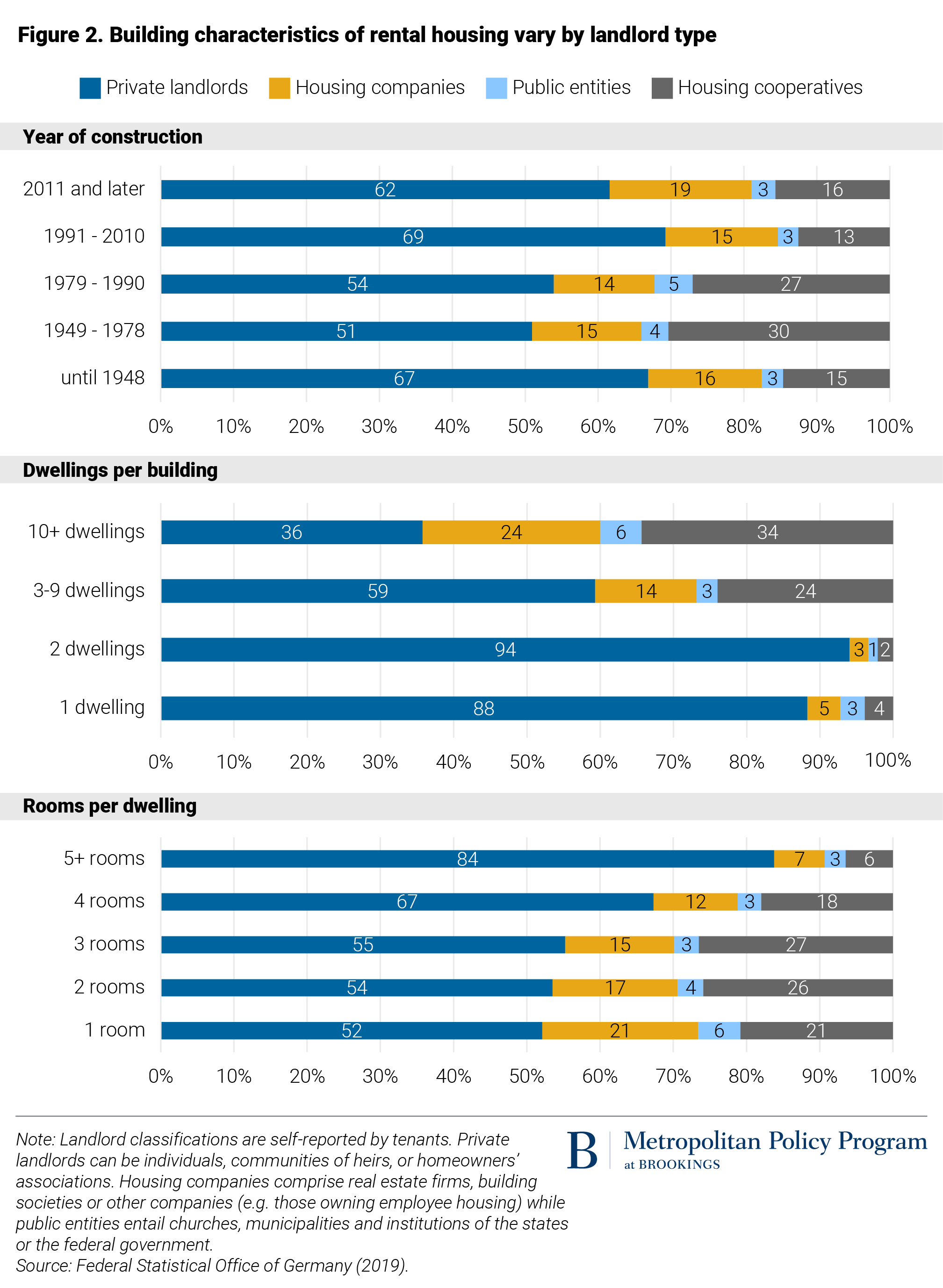

Private landlords own the vast majority of rental housing

Private landlords are an important pillar in the German rental housing market. More than half of landlords are non-professional owners—i.e., individuals, trusts, or homeowners’ associations (Figure 2). Public entities or privately owned housing companies own less than one-quarter of rental dwellings. Housing cooperatives own about one-quarter of the rental housing stock, mostly built between 1949 and 1990.

Private landlords predominantly own homes in buildings with fewer units but more rooms, such as single- and two-family homes or apartments in low-rise buildings. Many individuals rent out smaller apartments in their own home, similar to accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in the U.S.

Since the rental market is dominated by private landlords, housing finance is usually acquired through mortgages, typically with an amortization period of up to 30 years, interest rates fixed for five years or longer, and loan-to-value ratios of 82%.

New construction cannot keep up with increasing housing demand, especially in cities

In Germany, municipalities are responsible for earmarking land for construction and issuing building permits. New construction plummeted around 2008 to 2009. The gap between the number of building permits and completions has widened ever since, partly because of a shortage of skilled labor, the complexity of the building code, and high land prices—leading to a severe housing shortage, particularly in urban centers.

Developers can apply for subsidies such as grants or interest-free loans to construct social housing. Social housing developers have to rent their dwellings at below-market rates for a commitment period of typically 15 to 25 years, after which the units can be rented at market rate. However, fewer and fewer units are part of social housing, putting further pressure on low-income households. To counteract this trend, the federal government has earmarked a yearly sum of €1 billion for 2020 to 2024 to support the construction of social housing—30% less than in previous years.

There are a number of housing benefits available for households in need

To live in a social housing dwelling, households must apply for a certificate of eligibility. The criteria vary across federal states, but generally depend on household income. This certificate entitles them to apply for a social housing unit, but there are wait lists.

Households receiving certain social benefits and those with special needs can apply for housing assistance. Renter households that do not already receive any other transfers that include housing assistance can apply for housing benefit (Wohngeld), whichcovers part of the rent. The exact amount depends on the household size, total income, and the housing cost. Wohngeld legislation has been in place since 1965 in the former West German states and since 1991 in the former GDR, and continues to support about 550,000 households across the country, with the share of households being about 50% higher in East than in West Germany.

German rental markets are characterized by their renter-friendliness

Rental contracts are governed by the German Civil Code, and renter protection is a priority. Since the key elements of German rental housing are stability and security, leases are typically open-ended rather than on a yearly basis. Landlords have to ensure that the unit remains in good condition; the renter has to notify the landlord of any deficiencies not commensurate with reasonable wear and tear, and the landlord has to remedy these deficiencies quickly. Otherwise, the renter can achieve rent reduction or, in severe cases, termination without notice. The landlord, in turn, can pass certain costs and property taxes on to the renter but cannot raise the rent arbitrarily. In very tight markets, new rents for some homes cannot exceed the local average rent by more than 10% or are even capped temporarily.

Both parties have a notice period of three months; however, it is much harder for the landlord to terminate a lease than for the renter. For instance, termination is possible when the property is required for the landlord’s own use but not if the home is sold. Evictions can be enforced when the renter has been in arrears for at least two months, if they neglect, or if they sublet the dwelling without prior agreement. Evictions require the landlord to have issued a warning and terminated the lease first. If the renter does not vacate the home, the landlord can then ask for eviction at court.

Key challenges facing rental housing markets

Rising prices make housing less and less affordable in cities and exurbs

Rents for new leases have soared, with rents in major cities being affected the most. Rent-to-income ratios now average 27%—only slightly below what is deemed “affordable.” Moreover, rents per square meter gross of utility bills and rent-to-income ratios increase with municipality size. Therefore, measures such as rent control in some cities or a rent freeze in Berlin have been introduced. Both have had unintended consequences: Research on rent control and the rent freeze suggests adverse effects on the number of listed homes and household mobility. So far, not even the COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected the upward trend in housing prices, but this may change soon.

Renter households are more likely to be burdened and live in deprived conditions

While the cost of housing is increasing for both tenure types, renters report having higher housing cost burdens than owners: 16.5% of renters consider the financial burden heavy (compared to 10.5% of owners). In terms of the frequency of rent arrears and the share of households in need of housing assistance, there is still an East-West divide. This is mainly due to lower incomes and employment in the East even decades after the Reunification.

Even though housing quality is comparable among owner and renter households, renter households are more likely to be subject to housing deprivation. Also, overcrowding is more severe for renters than owners, and more so for those renting at reduced rent than for those renting at market price.

Germany’s aging population has special housing needs

Another challenge is the adaptation of the housing stock to accommodate the needs of an ever-aging population. Since older households tend to rent their homes, a sufficient number of rental units has to be accessible for those with mobility impairments. Statistics show that there is room for improvement.

Germany’s generous welfare system protected many households during the pandemic

People that lose their jobs and are unable to make ends meet are eligible for some type of housing assistance in Germany at any point in time. On top of this, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government enacted an eviction ban: Any rent arrears between April and June 2020 due to COVID-19-related job loss can be deferred until June 2022. Only if arrears have not been settled by then can the landlord take legal action.

Lastly, irrespective of the pandemic, renters’ right to physical integrity takes priority before landlords’ interests. This implies that renters whose contract is coming to an end cannot be forced to vacate the home if they are currently sick, even if this means that they will have to stay in the dwelling until after the end of their tenancy.

Conclusion

Renters in Germany are as diverse as owners, even though there are gaps in terms of nationality, wealth, income, age, and household size, to name a few. One of the most pressing problems of the past decade has been the soaring cost of housing (especially in urban centers), coupled with a high cost burden for lower-income households. And in the decades to come, another challenge will be to provide adequate housing for older households.