Evolution

Historically, schools have not been designed to engage families in the education of their children. As the idea of universal schooling spread around the globe—starting in Europe in the mid-1700s and spreading to the developing world in the latter half of the 1900s—the implicit understanding was communities would support school infrastructure (e.g. teacher housing, school buildings) and families would bring their children to the schoolhouse door and schools would take care of the rest (Lareau, 1987). In some communities around the world, this is still the prevailing mindset. The result has been that schools, which are not only social organizations but also products of society’s beliefs in any given era or context, have often operated with a missing tool in their toolbox: effective family-school engagement strategies.

This does not mean that families, particularly of the enfranchised and elite, did not develop strong opinions on where and with whom their children should attend school. In most countries, schooling was initially not expanded equally to all children. For example, in the United States, white boys have long been the principal beneficiaries, not girls or their black and brown peers (Reese, 2011). And when native Americans were included in schooling, it was often within a broader project of assimilation, breaking apart native families and cultures. At the same time, the colonial powers in Asia and Africa were using access to schooling as an explicit strategy to divide and conquer, with those allowed into school being groomed to help run the country via the colonial civil service. In sub-Saharan Africa, this opportunity frequently fell to the sons of tribal chiefs and few others. In most parts of the world, the role of power in society—whether political, economic, or cultural—is inextricably linked to the expansion of schooling story.

I can’t support my daughter at home if I don’t know what’s going on in the classroom.

Parent, United Kingdom

Hence, over the decades, schools have been caught in two competing dynamics. On the one hand, schools have increasingly become one of the main ways for individuals to advance in society (Baker, 2014). Today in the United States, for example, parents’ level of education is even more influential than their level of income on their children’s eventual economic position in society. This has led many highly educated parents to engage in what is characterized as “opportunity hoarding” behavior, namely actions that seek to ensure that their children have unfettered access to high-quality schooling (Reeves, 2017). On the other hand, schools have increasingly opened their doors to all children, especially in the latter half of the 20th century, both in response to government enforcement and with the rise of the powerful idea of inclusion and human rights—namely, that every child has a right to go to school no matter to whom or where they are born (United Nations, 1989).

Schools have long been handling the push-pull forces of inclusion (from first-generation learners to ethnic minorities) and pressure from elites who often fight to keep their children on top. This practice of pushback against inclusion has played out in different ways in different contexts. In Ghana, for example, when the government moved to a year-round schooling plan to admit all students qualified to enter senior secondary school, the most vocal opposition came from elite families whose students have traditionally been the few to attend senior secondary (Winthrop, 2020). In the United States, opportunity hoarding has left a long legacy, especially among white and well-to-do families who seek to exert power over schools—from opposing racial integration, to pulling children out of diverse inner-city schools and moving to the suburbs (Winerip, 2013), to even resorting recently to illegal schemes to ensure their children are admitted to prestigious colleges (Chappel & Kennedy, 2019).

Barriers to family-school engagement

This history helps put into context why today schools face three main, interrelated barriers to working with families to improve or transform education systems.

Schools and education personnel lack family engagement competencies and related training and support. Because working with families has not historically been at the heart of school design, education personnel have received only limited professional development or technical support on this topic. In the United States, for example, less than half of the 50 states require learning about effective family and community engagement strategies to become a school leader, and less than a third of states require it to become a teacher (National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement, 2020). Globally, family and community engagement also frequently gets short shrift in leadership and teacher development programs and policies.

I had to write to the school many times and asked them to get us involved: Why don’t we meet? Why don’t we talk? But the signature in the answers just read “Principal’s Office.” I didn’t even get a name.

Parent, Argentina

As a result, many jurisdiction leaders, schools, and their staff do not yet have the skill sets needed to effectively work with families both in navigating the frequent demands from elite parents and in effectively collaborating with parents from marginalized communities (Institute for Fiscal Studies & Innovations for Poverty Action, 2020; Mapp & Bergman, 2021). Without the training and skills to effectively build trusting relationships with families, miscommunication and misunderstanding can abound. As discussed below, this can result in families, especially from marginalized communities, feeling excluded. It can also result in school personnel, especially teachers, feeling blamed and disrespected by families (Schaedel et al., 2015). As one global teacher leader commented, “I recently spoke to a veteran teacher of 30 years who had a parent try and show her how to teach reading. She was understandably frustrated given she is a trained expert in the subject. This is not an uncommon experience for many teachers around the world” (D. Edwards, personal communication, February 2, 2018).

Families, especially from the most marginalized communities, feel uncertain and unwelcome in working with schools. Many families feel unsure of how they should engage with their children’s schools, or worse, they feel unwelcome (Cooper, 2009; Kim, 2009; Turney & Kao, 2009). Depending on context, this could be for a range of reasons—whether from lack of communication between teachers, school structures that do not adapt to parents’ realities, or a legacy of discrimination that parents experienced during their own schooling (Cashman et al., 2021; Hughes et al., 1994; Smith, 2000; Vincent, 1996).

I wish I was more educated about how you converse with teachers from the very beginning when my kids were little and not assume that the teacher is this expert who can’t be touched.

Parent, United States

In our focus group discussions across four countries (Botswana, Canada, India, and the United States) and a global private school chain (Nord Anglia), parents frequently mentioned that they would like to engage but lacked enough clarity or information from the school or teacher on how to do so. Parents also mentioned that schools were not set up to facilitate their engagement, citing examples such as teachers’ limited time to speak with them throughout the year, scheduling of school events when parents were working, and parents’ own limited money or time to fulfill schools’ requests. In addition, without respectful relationships and two-way communication, teachers and education leaders may rely on inaccurate assumptions about the worldviews, experiences, and social capital of certain groups of parents (Crozier & Davies, 2007; Horvat et al., 2003; Kao & Rutherford, 2007; Kim & Schneider, 2005; Rudney, 2005).

When parents disregard teachers, it is hard to stand before the students and play an active role as an elder.

Teacher, Botswana

Family-school engagement receives limited attention, research, and funding. A committed community of researchers and practitioners has led the field in gathering evidence, testing strategies, and advancing solutions on family-school engagement, but they have not received the attention or support they deserve. The literature on family-school engagement is diverse, including evidence-based compendiums focused on the U.S., Europe, and the developing world (Epstein et al., 2018; Nishimura, 2020; Paseka & Bryne, 2020). However, before the pandemic, this had been a comparatively small area of focus for education researchers and reformers. In the U.S. Department of Education’s Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) database, searches for articles between 2001 and 2019 using the keyword “teachers” yielded four times the citations of searches using the keyword “parents.” It remains to be seen if COVID-19 may lead to long-term change in this regard.

If we take a look at the role of parents in education, in the public school space, it’s very limited. Historically, there has not been space for parents to have a voice in what and how schools teach children. Parents’ participation has been limited to payment of additional fees.

Minister of Education, Ghana

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Harvard Graduate School of Education surveyed educators and education administrators across 59 countries in April–May 2020 about their schools’ experiences, including their reopening strategies in the COVID-19 environment. Three-quarters of the respondents stated that the reopening plans were developed collaboratively with teachers, but only 25 percent said that the collaboration included parents as well (Reimers & Schleicher, 2020). Education philanthropy is another place where parents are often excluded from the conversation. By one estimate from John King, former U.S. Secretary of Education, investment that focuses on families’ wants and needs receives only 2 percent of philanthropic funding in the United States (New Profit, 2019).

The evolving approach to engagement

Education systems’ approach to family-school engagement has evolved over the years. One of the most influential frameworks was developed in the early 1990s by Joyce Epstein and her colleagues. Identifying six main types of parental involvement in their children’s schooling—parenting, communicating, volunteering, learning at home, decisionmaking, and collaborating with the community—this framework quickly became widely used around the world (Epstein, 1996).

Subsequent research reviewing the effectiveness of these different types of parental involvement demonstrated that not all were equally helpful in improving children’s school-related outcomes such as attendance, completion, grades, literacy and numeracy exam scores, and socio-emotional competencies (Henderson & Mapp, 2002). Family-school engagement activities that were intermittent, ad hoc, and not closely tied to children’s school learning, such as attending events or volunteering at school, were not as impactful as other approaches. The most effective means were the more-sustained types of engagement that were linked to learning—including family-teacher partnership on goal setting, timely two-way communication between parents and teachers, assistance to parents in supporting their children’s learning outside of school, integration of families’ unique knowledge into teaching at school, and codesigning of family-school engagement approaches (Dowd et al., 2017; National Association for the Education of Young Children, n.d.).

Today, experts often distinguish between family involvement and family engagement. As Ferlazzo (2011, p. 12) puts it, “A school striving for family involvement often leads with its mouth—identifying projects, needs, and goals and then telling parents how they can contribute. A school striving for parent engagement leads with its ears—listening to what parents think, dream, and worry about. The goal of family engagement is not to serve clients but to gain partners.”

A family involvement approach can be helpful depending on the goal. For example, behavioral economists have demonstrated the significant impact when schools send families “nudges” by either letter or text message, which can increase students’ attendance, reduce dropouts, and sometimes improve learning (Kraft & Rogers, 2015; Education Endowment Foundation, n.d.-b). However, there is a growing consensus that family engagement, which gives more power and agency to parents and welcomes them in as equal partners, should be at the heart of how families and schools work together (Weiss et al., 2018). This is why, reflecting the importance of true collaboration, we use the term “family-school engagement” in this playbook.

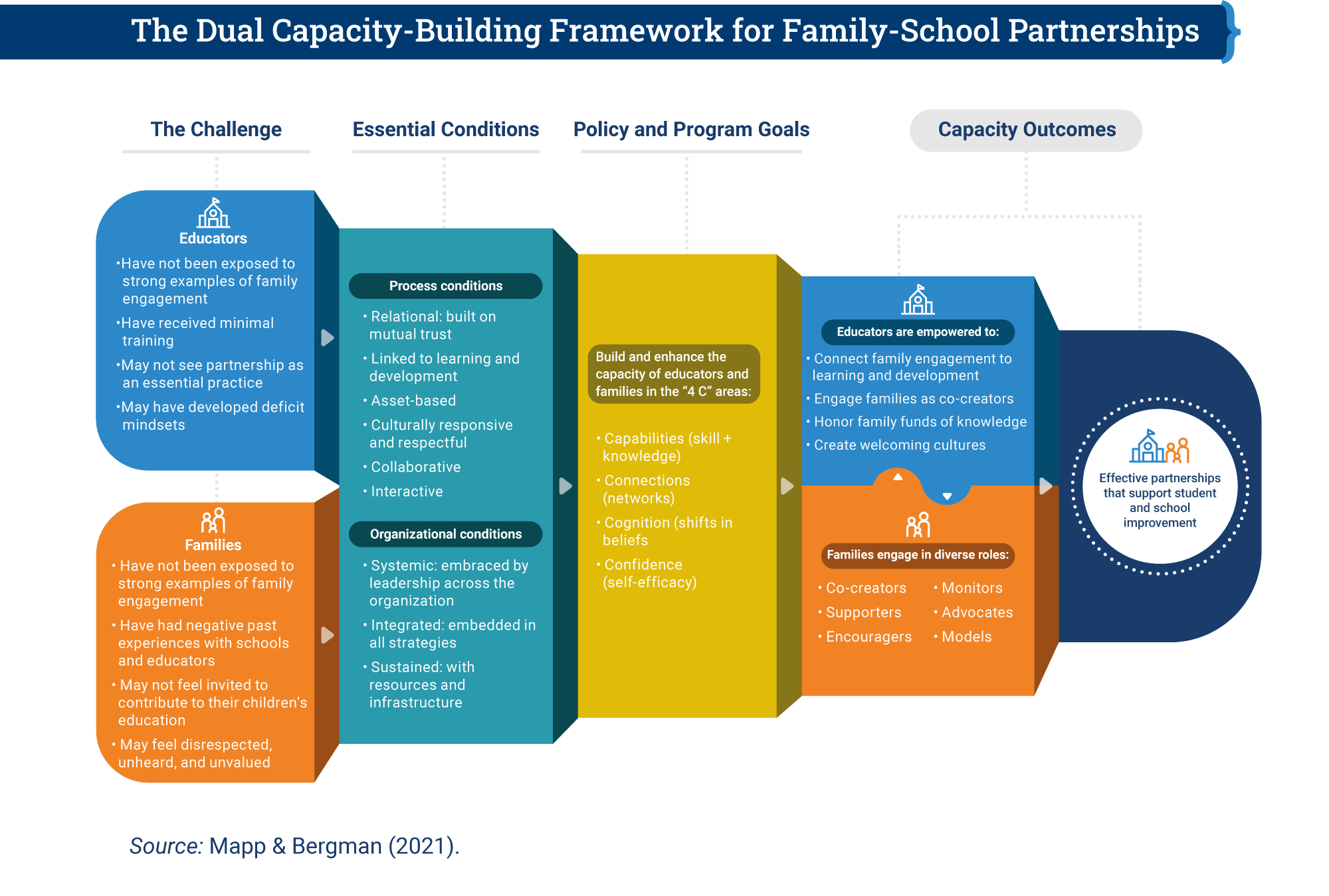

One recent framework that embraces this vision proposes that family-school engagement be an ongoing practice or way of doing things rather than a stand-alone program. It envisions family-school engagement as something everyone in the school does every day rather than as the responsibility of one person or team inside the school. This framework, called the Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships (Figure 2), spells out the essential conditions for effective family-school engagement and argues that families and schools have equally important, mutually supporting roles (Mapp & Bergman, 2021). The framework centers on respectful relationships between families and schools, arguing that “deficit-based” mindsets far too often get in the way—as a result, seeing each other’s weaknesses rather than strengths. The goal is to build the capacity of education personnel and families in four areas: capabilities (skills and knowledge), connections (networks), cognition (shifts in beliefs and values), and confidence (self-efficacy).

FIGURE 2

Contextualizing family-school engagement

The various approaches to family-school engagement must ultimately be adapted to community-specific contexts. How schooling is perceived in communities around the world is not uniform. Some communities focus more on the collective benefits of having children educated in their community, while others tend to focus on the individual benefits to their children only (Kim, 2018). In some communities, families see school outreach to seek their engagement as a sign of unprofessional behavior or weakness. In other communities, parents feel they have no place in school-related discussions. It is important to consider which approach—from involvement to engagement—would be most appropriate to achieve a given goal in a given context.

Illustrating this point are the contrasting cases of two programs in Ghana that seek to support children’s early learning outcomes, from academic to socio-emotional competencies. In rural Ghana, families, especially mothers—many of whom have not attended school themselves—frequently do not believe it is their role to help with their children’s education. One initiative, Lively Minds, works closely with rural mothers to identify how they can, and would like to, play a role in their children’s early education. Years of deep engagement in building relationships and trust have blossomed into innovative approaches enabling families and schools to work together to the significant benefit of children (Institute for Fiscal Studies & Innovations for Poverty Action [IFS & IPA], 2019).

However, another program to improve early learning in working-class urban schools operated in very different environments—where parents frequently dedicate large amounts of time and resources to supporting their children’s schooling. One teacher training program in this context rolled out effective teaching strategies for playful learning that markedly improved children’s outcomes but only when parents were not involved (Wolf et al., 2019). In some of the schools, the program chose a typical “family involvement” strategy of informing families in presentations and videos at school meetings about these new interactive, child-centered teaching methods. But children in these schools performed worse than the control group, perhaps because parents worried that the new teaching style was not rigorous enough. Given that Ghanaian parents view the purpose of preschool as preparation for primary school through academic learning and socialization (Kabay et al., 2017), it could be that they doubled down on “drill and kill” methods at home, undermining the more engaging learning experiences in the classroom. It could also be that parents’ interaction with teachers discouraged teachers from fully embracing their new training, because, in the schools with parent involvement meetings, teachers became less likely over time to use the interactive teaching and learning methods in the classroom.

Ultimately, these examples point to the importance of carefully considering what will be effective family-school engagement approaches in each context. Essential elements include the extent to which trust has been built—both between families and schools in general and between teachers and parents individually.

The importance of trust

Relational trust is emerging as an important factor underlying effective family-school engagement. When such engagement interventions fail, as described above and documented by others (Education Endowment Foundation, n.d.-a), they likely were not only poorly designed but also failed to build the necessary trust between families and schools. Relational trust was an important driver in the Chicago study showing that students in schools with strong family-school engagement are 10 times more likely to improve academically (Bryk, 2010).

There are always reasons for a lack of parent engagement. It may come across as parents not liking us teachers or not being a supportive parent, but there’s always a reason behind it. And so if you can identify that, you can build that relationship.

Teacher, United States

In an earlier study of Chicago schools, researchers described relational trust as being built out of the daily interactions that take place in the school community, including between families and schools:

As individuals interact with one another around the work of schooling, they are constantly discerning the intentions embedded in the actions of others. They consider how others’ efforts advance their own interests or impinge on their own self-esteem. They ask whether others’ behavior reflects appropriately on their moral obligations to educate children well. These discernments take into account the history of previous interactions. In the absence of prior contact, participants may rely on the general reputation of the other and also on commonalities of race, gender, age, religion, or upbringing. These discernments tend to organize around four specific considerations: respect, personal regard, competence in core role responsibilities, and personal integrity. (Schneider, 2003)

Relational trust is generated when interactions are characterized by respectful exchanges, when people are willing to go above and beyond what their role dictates, and when people do what they say will do. And it can be a powerful driver of outcomes. In one study, trust between teachers, principals, parents, and students accounted for 78 percent of the variance in achievement on standardized reading and math assessments (Tschannen-Moran, 2014). Two variables made strong independent contributions to this variance: teachers’ trust in students and parents, and students’ trust in their teachers.

The importance of the teacher-parent relationship

Trusting relationships between parents and teachers have been shown to help students in numerous ways, including:

- Learning the knowledge taught in school through parental modeling and reinforcement at home (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1995).

- Setting shared goals, including classroom learning activities that parents can support at home (Christenson, 1995).

- Reducing behavior problems (Epstein & Sheldon, 2002).

- Increasing teachers’ understanding and empathy for their students’ lives outside of school (Valdés, 1996).

Ongoing communication is essential to these relationships. For example, teachers can advise parents on how best to reinforce skills learned in school—something that is especially important given that, as we saw in the case of Ghana above, when parents are unsure of how to support their children’s homework, their involvement can be counterproductive to academic success (Fan & Chen, 2001).

If the teachers are open, I can go to the teacher to speak to them and we are able to speak about different things about the child. I trust that they can produce results that I would be happy about as a parent.

Parent, Botswana

Family-school engagement can help parents and teachers communicate to determine higher expectations for students, which is of particular importance. Research has shown that parental expectations of a child’s ability has a stronger effect on academic achievement than other aspects of parental involvement such as helping with homework and overall parenting style (Fan & Chen, 2001; Jeynes, 2007).

For further details about how effective family-school engagement can help improve and transform education systems, see the background paper, “Understanding the connection between family-school engagement and education system transformation: A review of concepts and evidence.”