Aligning beliefs

A framework

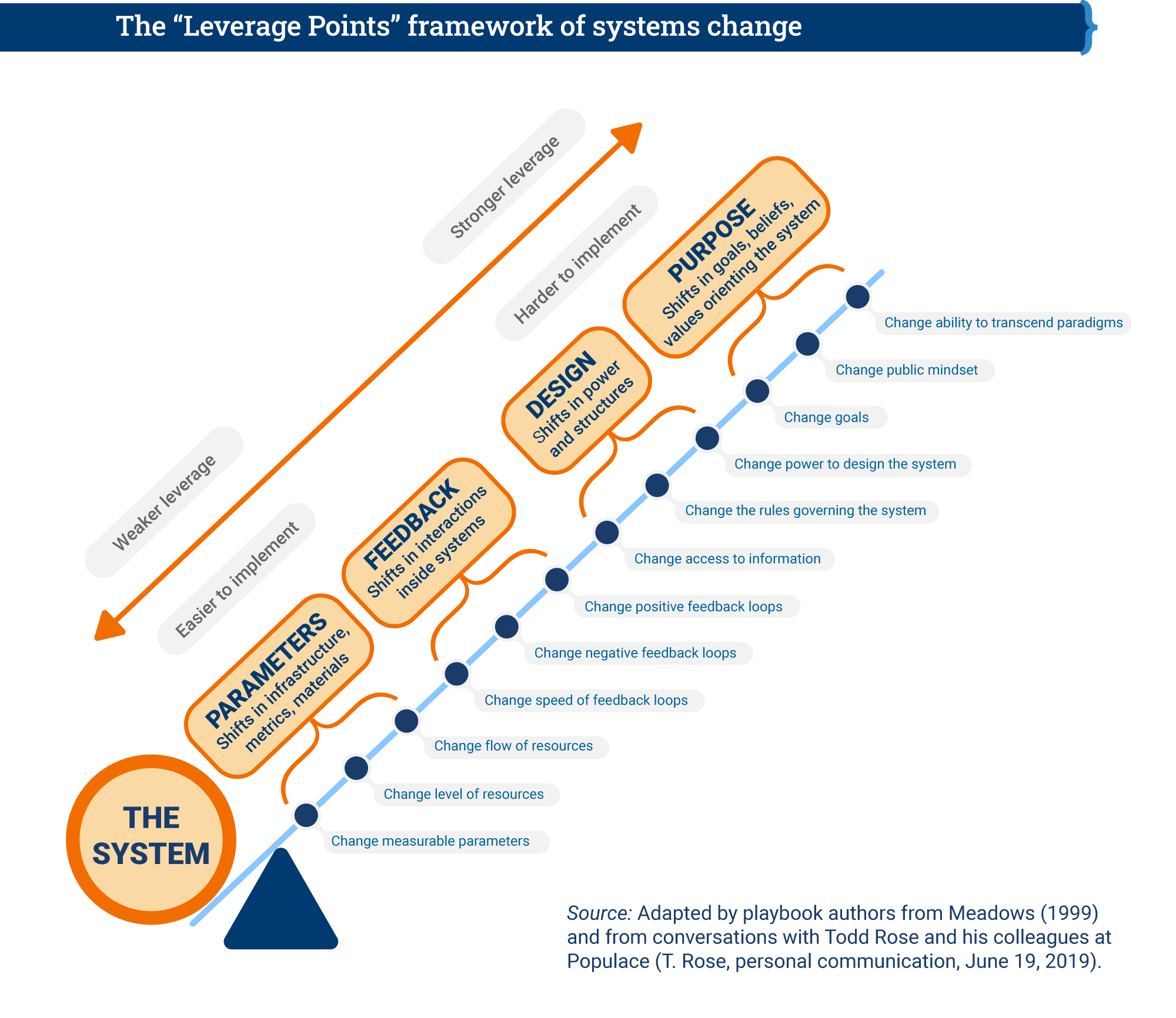

As discussed in the Overview, beliefs about the purpose of school drive the “deep structures” of education systems. They are also “high leverage points” for transformation. Myriad frameworks exist for understanding systems change, cutting across fields and disciplines. Each presents a unique angle, such as a focus on collective creativity (Liedtka et al., 2017) or networked learning (Bryk et al., 2011). Among them, the “Leverage Points” framework by American systems theorist Donella Meadows stands out for demonstrating the comparative power of different change approaches—a scale of ways to change a system (Meadows, 2008). Her framework builds on decades of research into complex human-environment systems, reflecting a wealth of empirical data on how people affect and are affected by their contexts, from the natural world to institutions. It is among the few frameworks that serve as both a utility-based classification system and a practical tool. Its insights prove useful for scholars and practitioners alike (Figure 5).

Most importantly, the Leverage Points framework has been shown to work. Since its publication in 1999, a wealth of evidence has emerged to support the model. It has been cited extensively in the sustainable development literature as a path to impact and efficiency (Abson et al., 2017; Hjorth & Bagheri, 2006). Health systems analysts have popularized the work as well; in fact, a 2009 report by the World Health Organization proposed systems-strengthening activities using Meadows’s paradigm (World Health Organization, 2009).

The Leverage Points framework identifies and arranges 12 ways to intervene in a system, in order of transformative power from weakest to strongest (Meadows, 2008). Interventions such as shifting parameters (like reading benchmarks and funding per pupil) or remaking physical infrastructure populate the base of this hierarchy. Changing parameters or shifting feedback loops are visible and practical steps to help shift systems and hence often receive the most attention from decisionmakers. Although they are crucial to system functioning, their transformative power lies only in their alignment with and support of the points at the top of the framework.

Topping the list are transformations in system design and system goals and paradigms. Structural shifts in power and rules that govern the design of a system and hence manage the parameters and feedback loops are essential for system transformation. But ultimately, the most important shift is in the purpose of the system—in our shared beliefs and values. According to Meadows, changing mindsets and paradigms can have a profound impact because they guide behavior (Meadows, 1999). Put simply, this means that the most powerful change involves shifting collective purposes and mindsets. In practice, this involves not simply redefining a system’s purpose but also showing why existing practices do not fit with those purported goals. This shift forces system members to confront the misalignment between their perceptions and lived reality—between deeply held beliefs and an outmoded systems logic.

Every single policy I was doing, I was testing it with parents and teachers and principals. Three times a week. It looks very obvious, but it had never happened. The parents were like ‘You were sent by the ministry?’ I had to say, ‘No, I’m the minister! Let me sit down and talk.

State Minister of Education, Argentina

This is why family-school engagement is so important to transforming education systems. Collective alignment behind a shared vision on the purpose of education will shape how systems are designed, what feedback loops are needed, and what parameters should be put in place to achieve the shared vision. Achieving this type of alignment is not easy and requires deep engagement on the fundamental beliefs about education across a wide range of stakeholders in a system (like school administrators, teachers, families, students, community members, and employers). It is for this reason that together with FEEN we have explored the educational beliefs of parents and teachers.

FIGURE 5

Parent beliefs about education

Many studies examine parent and family perspectives and beliefs about education. These studies range from assessing parents’ satisfaction and experience with their child’s schools to understanding parents’ beliefs about their role in supporting their child’s education to examining the school characteristics that parents value most. For example, parental satisfaction with school is regularly tracked in some countries and generally family members satisfaction of their child’s school is high, often higher than the satisfaction levels of the general public (Brenan, 2021). The reason for this could be attributed to various factors, as discussed below.

However, in general, understanding parental satisfaction only provides a limited “quick picture” of parental perspectives on education. Some studies examine if family members have an accurate picture of the quality of their children’s school. The results vary depending on context. For example, in the United States parents frequently believe their child is excelling academically when he or she is not, but in Pakistan parents usually accurately assess not only their child’s academic level but also the quality of the schools in their community (Andrabi et al., 2008; Learning Heroes, 2020). Other studies look to parents’ experiences of their child’s school, such as if the school climate is welcoming and if they have a trusting relationship with their child’s teachers (Queensland Government Department of Education, 2019).

Another area of research examines the underlying beliefs influencing parents’ experience, perception, and behavior related to their child’s education. For example, some research examines what motivates parents to be involved in their child’s education noting it is heavily influenced by their “role beliefs” or what they believe their role is in their child’s education and their beliefs on their own “efficacy” or ability to positively contribute to their child’s educational progress and outcomes (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1997). Notably, parents’ level of education and socio-economic status has a complex relationship to parental engagement across contexts. In the United States, for example, one study forcefully rejected “the culture of poverty thesis” that working class families cared less or were significantly less involved in their child’s education while the same researchers found that this was not the case in Hong Kong (Ho, 2006; Ho & Willms, 1996). Other research examines parents’ beliefs about the skills children should develop with variable findings across contexts: parents have different perspectives on what types of competencies are the responsibility of families to teach children above and beyond academics, which most families strongly agree is an important role for the school (Care et al., 2017). Some studies point to the contrasting perspectives between parents and teachers on what the most important competencies are, especially in early learning, for children to develop (Jukes et al., 2018). While still other studies try to understand what parents believe makes a good school, including by looking at how parents choose schools. Around the world, studies from Kenya to India to Brazil to Europe and beyond highlight that parents often look to homework, discipline and school environment, safety, test scores, teacher attendance, distance, school reputation among other things, as indicators of what makes for a good school for their child (Gallego & Hernando, 2009; Lohan et al., 2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2015; Plano CDE & Omidyar Network, 2017; Varkey Foundation, 2018; Zuilkowski et al., 2018).

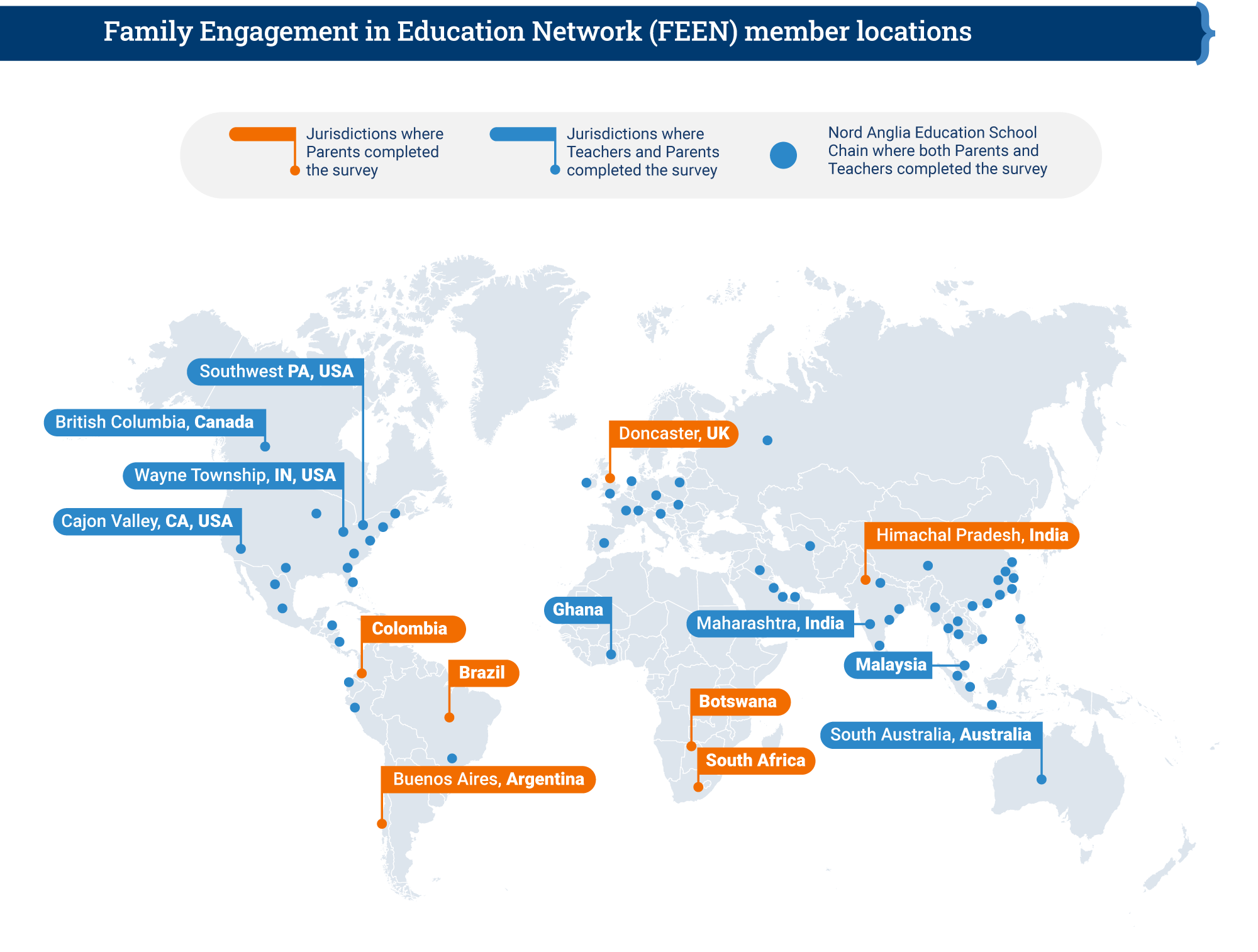

To date, however, little empirical research has examined parents’ overall beliefs on the purposes of school and education. A qualitative study in New Zealand explored students’, parents’, and teachers’ beliefs about the purpose of school and found limited attention to the economic purpose, namely preparing students for the world of work (Widdowson et al., 2014). Whereas other studies in the United States highlight how parents focus more on their child’s happiness and wellbeing in relation to school when their child is younger and shift their focus to their child’s academic preparation when their child is older (Learning Heroes, 2017). System transformation efforts require us to dig deeper and ask questions above and beyond what frequently is studied in family-school engagement. We sought to add to the existing family-school engagement evidence base by conducting surveys of 24,759 parents across 14 jurisdiction clusters and 6,146 teachers across 8 jurisdictions—in all, spanning 10 countries and one global private sector school chain—between May 14, 2020, and March 9, 2021 (see Figure 6). We asked questions about parents’ and teachers’ beliefs about the most important purpose of school, what a quality education looks like, what types of teaching and learning experiences they thought were most important for their children and students, and how their educational beliefs were formed (see Box 6). Our goal was to delve deeply into guiding values and beliefs and to surface a detailed picture of family and teacher mindsets—insights that are important if families and schools are to work together to redefine the purpose of school for students.

We conducted these surveys in close collaboration with several of the project collaborators in our Family Engagement in Education Network (FEEN) (see Box 7). Project collaborators were invited to join the network based on several criteria such as their focus on addressing equity in highly diverse populations of students, their commitment to providing a quality 21st-century education, and their interest in sharing and learning about how families and schools can work better together. Many jurisdictions already had ongoing family-school engagement initiatives when they joined FEEN. Hence this is not a randomly selected set of jurisdictions, and the survey findings should be read with that in mind.

Defining concepts in the CUE parent and teacher surveys

Here we summarize the concepts used in our surveys. These descriptions, however, do not represent how the questions were worded for respondents.

Purpose: What is the most important reason for parents to send their children to school and for teachers to teach them: the academic, economic, civic, or socio-emotional development of the students?

Pedagogy: What pedagogical approaches do parents and teachers prefer: innovative pedagogy (e.g., interactive, experiential, playful) or traditional pedagogy (e.g., teacher-led instruction in person or online)?

Indicators of quality: When are parents and teachers most satisfied with their children’s or students’ school: when they see academic indicators of quality (e.g., when students are achieving at grade level, getting good grades on exams, being prepared for postsecondary) or well-being indicators (e.g., when students are enjoying school, developing friendships and social skills, participating in extracurricular activities)?

Sources of information: Who influences parents’ beliefs about education:

- (a) Education-related sources (e.g., actors directly involved in education such as teachers, school leaders, higher education admissions criteria, scientific research from the learning sciences); or (b) non-education-related sources (e.g., actors related to the community at large such as other parents, civil society or faith-based leaders, elected officials, the media).

- (a) Close sources (e.g., actors who are part of parents’ daily lives such as other parents, teachers, school leaders, civil society leaders, and elected officials); or (b) far sources (e.g., actors that are unlikely to be part of parents’ daily lives such as the media, higher education admissions officers, scientific findings).

Trust: To what extent do parents believe their child’s teacher is receptive to their inputs and suggestions?

Alignment: To what extent do parents believe their child’s teacher shares their beliefs about what makes a good-quality education for their child?

FIGURE 6

CUE’s Family Engagement in Education Network and its role in the parent and teacher surveys

The Family Engagement in Education Network (FEEN) consists of 49 project collaborators (32 governments, 14 civil society and funder organizations, and 3 private school networks) from 12 countries around the world and one global private sector school chain with schools in 31 countries (Nord Anglia Education).

For coordination and data analysis purposes, project collaborators are grouped into 16 jurisdiction clusters (e.g., we have grouped the 15 school districts located in Southwestern Pennsylvania together). These jurisdiction clusters include Botswana; Brazil; British Columbia, Canada; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Cajon Valley, California, U.S.; Colombia; Doncaster, U.K.; Ghana; Himachal Pradesh, India; Maharashtra, India; Malaysia; Nord Anglia Education; South Africa; southwestern Pennsylvania, U.S.; South Australia, Australia; and Wayne Township, Indiana, U.S.

Parent surveys were conducted across 14 jurisdiction clusters spanning 10 countries and Nord Anglia Education, while teacher surveys were conducted across 8 jurisdiction clusters from across 5 countries and Nord Anglia Education.

Parent and teacher insights

We learned a great deal from parents and teachers in these surveys, as our top five insights across all the jurisdictions indicate below. However, one surprise, which is in line with findings from other surveys discussed above, is that parents report resoundingly that they are satisfied with their child’s education. This especially surprised us, considering that parents completed our survey during COVID-19 school closures, when many were coping with difficult changes to schooling. Parents might tend to respond favorably to these general satisfaction questions, even amid dire circumstances, for many reasons: They could, of course, be very happy with the school. They could be grateful for the custodial care of their children. They could also want to show their gratitude for the teachers’ efforts. Or they might have little else to compare the school with (especially if they have limited education themselves). Finally, they might find it hard to admit, even to themselves, that the school they send their children to everyday does not meet their expectations.

We really need to teach in school, how important it is to be kind to each other, to accept people’s differences, and learn about people’s differences.

Parent, United Kingdom

Beyond parents’ level of satisfaction, we ultimately found that the parents in each jurisdiction have a unique set of beliefs and expectations—and that frequently there is misalignment between parents and teachers. While there are some common themes across jurisdictions, as covered below, the differences between them confirm a central conclusion: for any school or education system seeking to redefine the purpose of school for students and therefore to determine the operational practices to deliver on this goal, a better understanding of parents’ and teachers’ beliefs is an important place to start.

The following section of this playbook provides a set of Conversation Starter tools adapted from our parent and teacher surveys to guide those wishing to embark on this journey. For a detailed discussion of the survey methods and findings, please see “What we have learned from parents: A review of CUE’s parent survey findings by jurisdiction.”

Insight No. 1: Different communities have different motivations

Perhaps the most important insight is that it is risky to assume you understand family beliefs and perceptions about what makes for a quality education without asking families directly. Although the surveys reveal some similar patterns across jurisdictions, each context presents a unique picture of what parents value and perceive to be true. It is especially important to guard against long-standing narratives in education about the ways in which parents’ socio-economic status shapes their beliefs about what a quality education looks like for their child, such as assuming that low-income parents are more focused on school as a means for their children to get a job and advance economically. In fact, our data across jurisdictions reveal no consistent relationship between parents’ level of education (a good indication of socio-economic status) and their educational beliefs.

If nothing else, this data has shown us that it is important for school and jurisdiction leaders to spend the time to get to know the parents in their community and what their beliefs, motivations, and perceptions are around education. Indeed, this is why, in the findings that follow, we present the data by each jurisdiction separately rather than as an aggregate picture. The connections, relationships, and trust that can develop between families and schools from such an exercise would be helpful across the board, regardless of whether the interest is in improving systems or in transforming them. But understanding parents’ beliefs and perceptions about the purpose and related experiences of schooling must be an integral part to any endeavor to transform education systems.

My son, he is doing well with academics. Still, I feel they [teachers] should do something for self-growth.

Parent, India

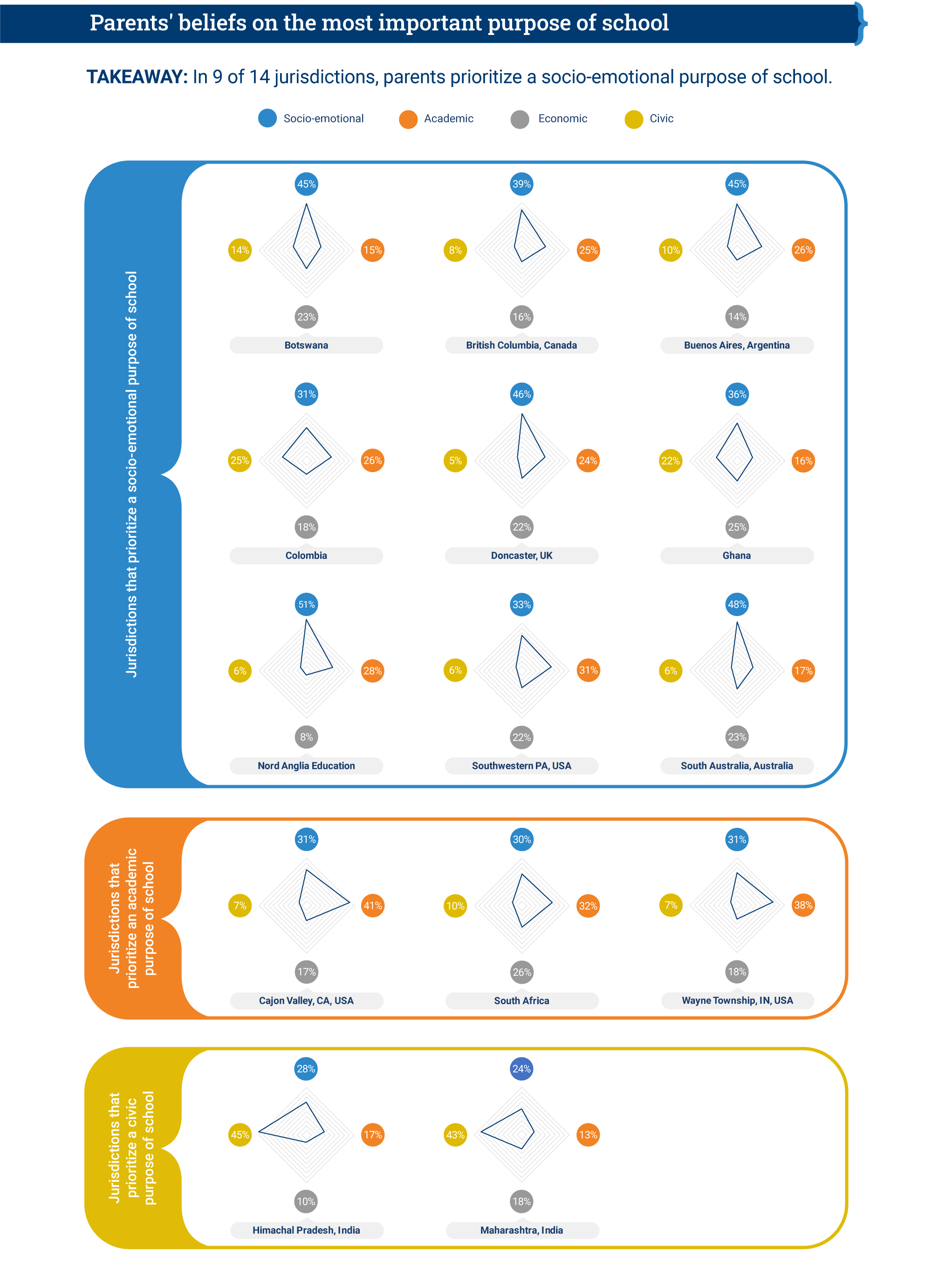

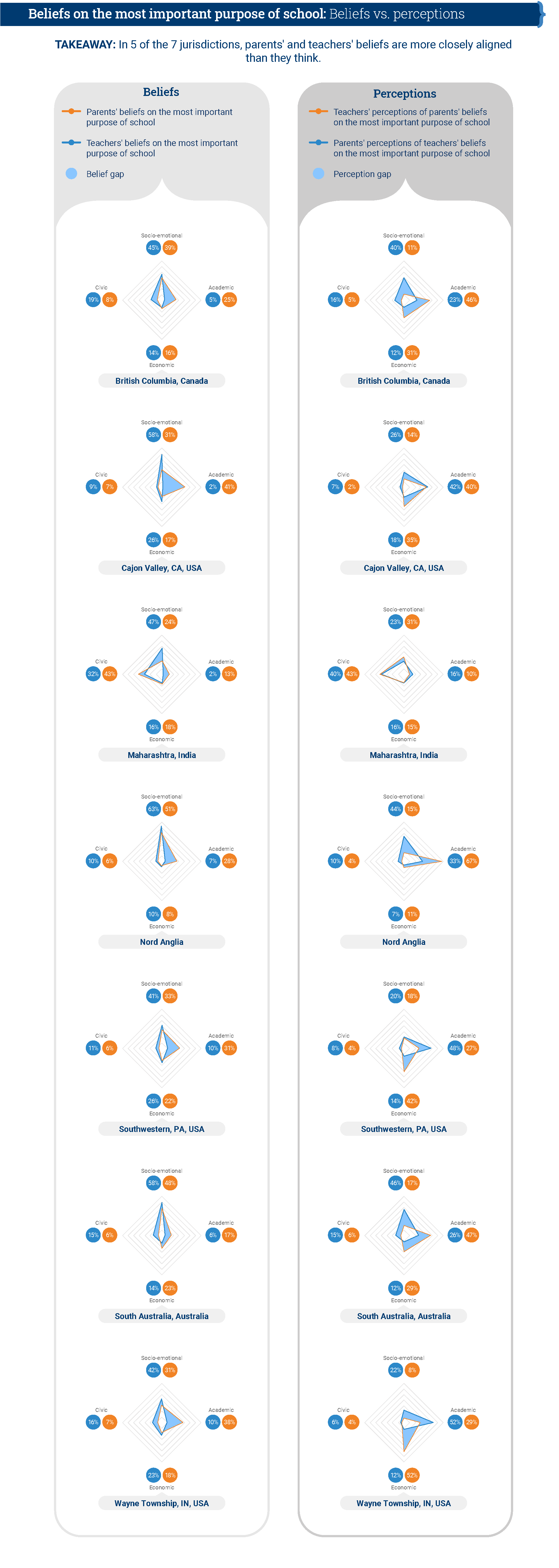

Insight No. 2: Both parents and teachers broadly support a holistic vision of education, but each group believes the other is narrowly focused on academics

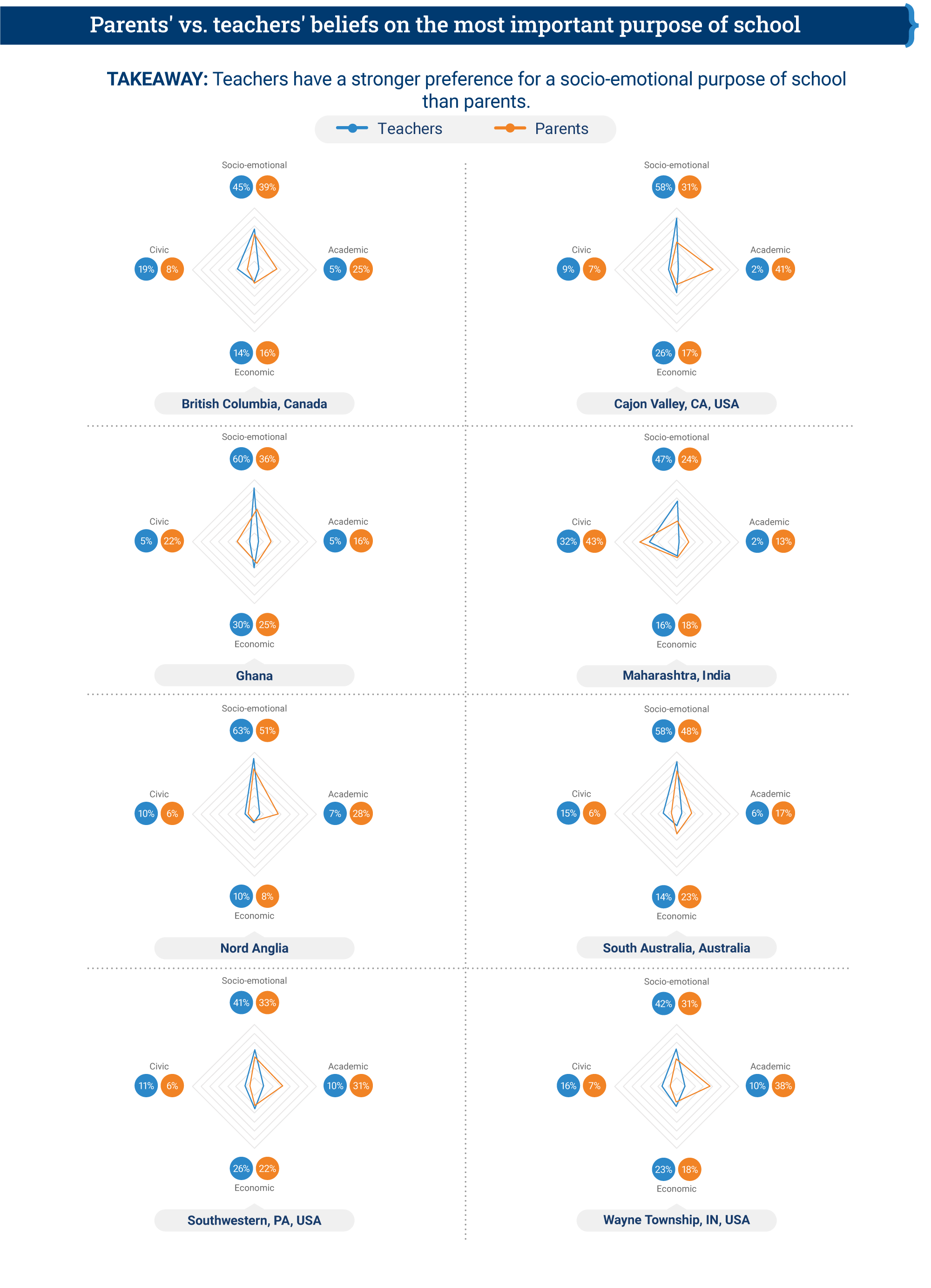

Each jurisdiction has a particular prevailing set of beliefs that parents hold about the purpose of school, the pedagogy they support, and the indicators of quality they think are most important. Across jurisdictions, however, there is strong support for a holistic vision of school. Many parents prioritize their child’s socio-emotional development equally to, if not more than, their academic development as the most important purpose of school. This is the case in 9 of the 14 jurisdictions (Figure 7).

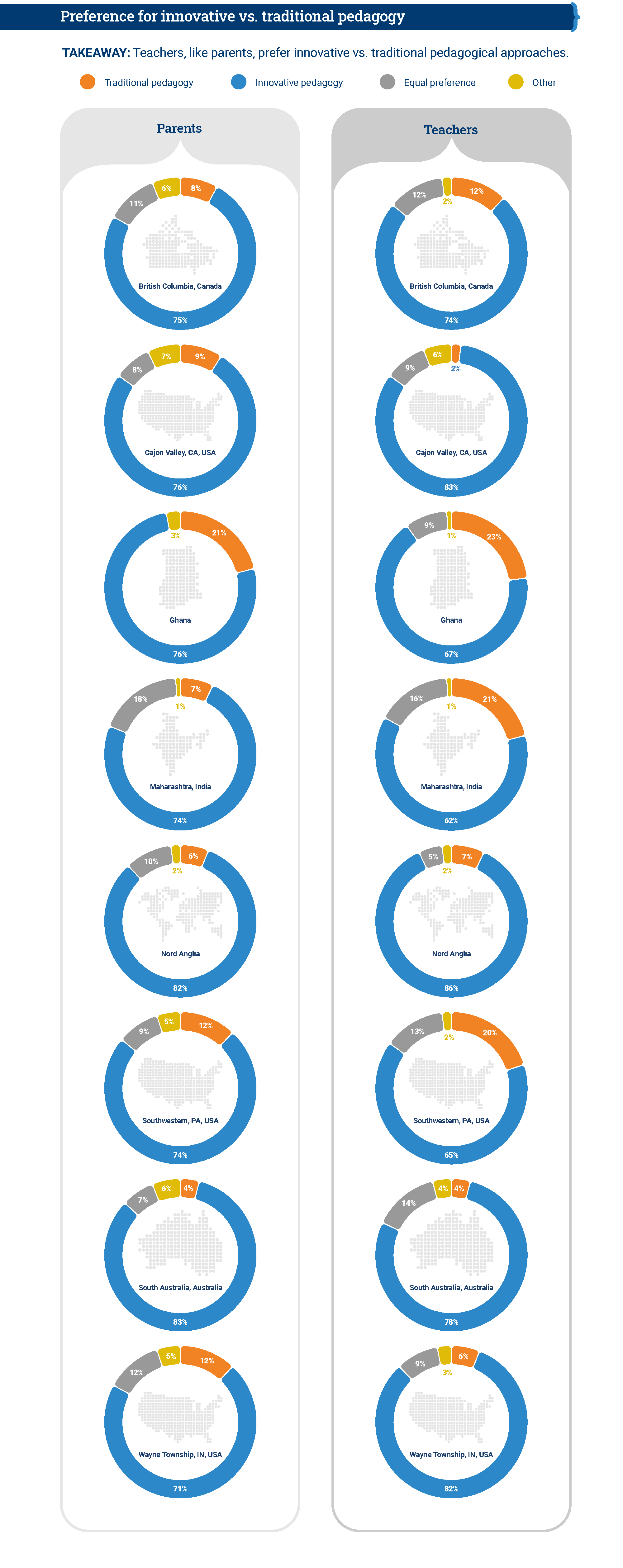

Relatedly, parents in all but one jurisdiction prioritize approaches that are interactive and experiential over didactic, teacher-led instruction methods when asked to rank their preferred ways of teaching and learning for their children during school closures from a list of pedagogies. Interestingly, in South Africa, parents report a preference for didactic, traditional approaches when presented with a list of pedagogies but prefer interactive, innovative methods when asked to choose between two contrasting vignettes that describe a classroom where teachers use interactive pedagogy versus a classroom where teachers use direct instruction. To test a novel approach to surveying, we included this vignette-based question in the Colombia, Ghana, and South Africa parent surveys (Winthrop & Ershadi, 2020). This discrepancy may be because parents in South Africa are generally supportive of what we term innovative pedagogy, namely interactive and experiential teaching and learning approaches, as seen by their response to the vignette question; but had reservations about specific types of pedagogies we classified as innovative as seen from their limited support for playing games (on or offline) when ranking their preferences.

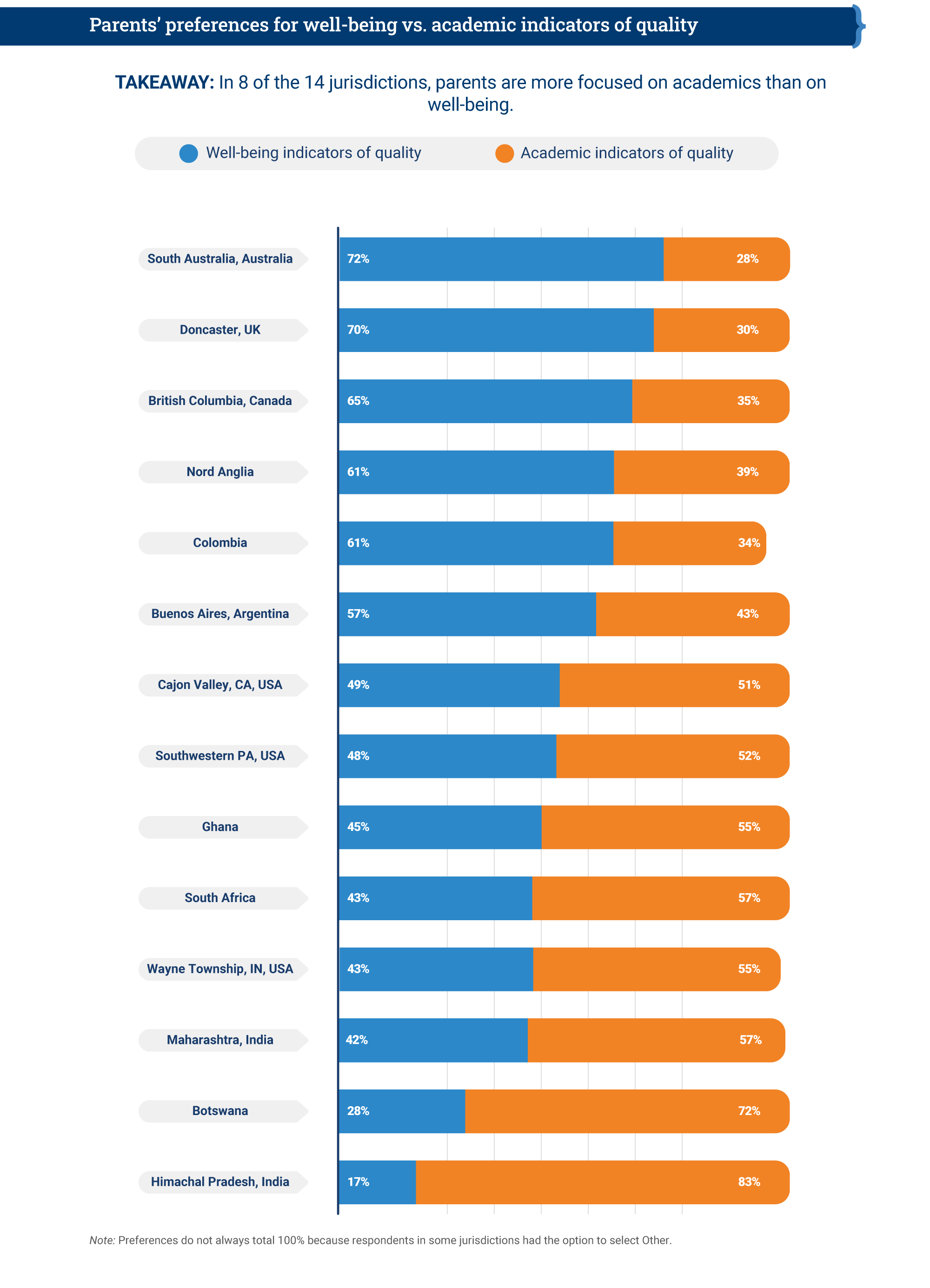

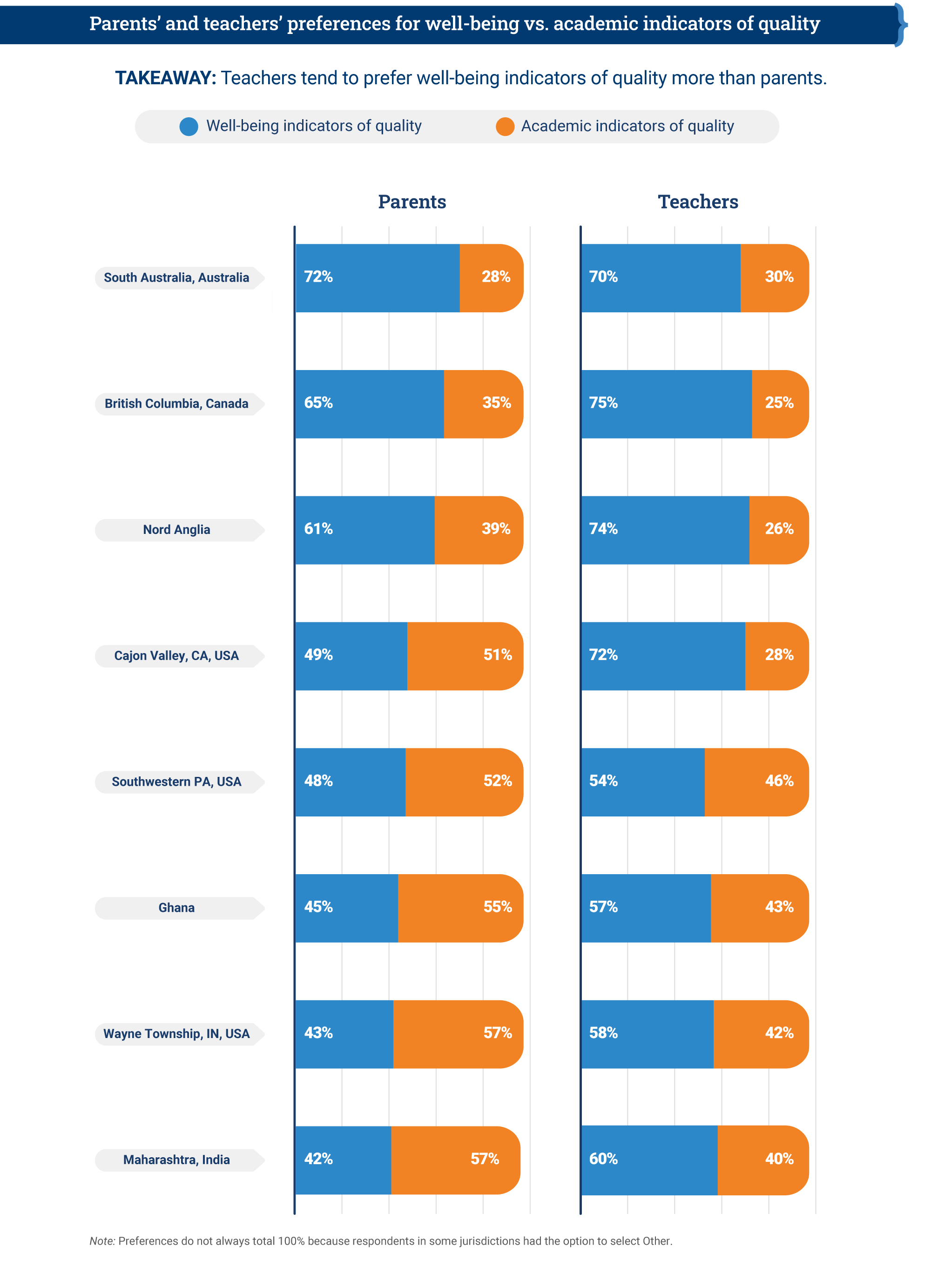

The surveys also included questions to understand which indicators of quality most inform parents’ assessment of their child’s school, divided into two main categories: academic indicators and well-being indicators. These questions elicited more of a mixed response across jurisdictions (Figure 8). In 8 of the 14 jurisdictions, parents are more focused on academic indicators than on well-being indicators, even though parents in many of these same jurisdictions also believe that the socio-emotional or civic purpose of school is the most important. In these jurisdictions, parents are most satisfied when their children are performing at grade level, doing well on exams, and preparing for postsecondary education. In the other 6 jurisdictions, parents are more satisfied when they see indicators of children’s well-being like making friends, enjoying school, and participating in extracurricular activities.

Students have to be able to write and think and tell. They have to have an opinion on the subject they study.

Parent, United States

The availability of different indicators on children’s experience in school may be one reason why in some jurisdictions, such as Botswana, parents believe that children’s socio-emotional development is the most important purpose of school, but they rely heavily on academic indicators to assess the quality of their child’s school. It could simply be that exam pass rates and other similar indicators are all the information they are receiving.

FIGURE 7

FIGURE 8

Teachers, in all eight jurisdictions where we surveyed them, hold much more cohesive views than parents about both the purpose of education and the indicators they focus on for achieving a quality school experience. They overwhelmingly identify the socio-emotional purpose of school as most important and identify the well-being indicators of quality as the most important for students (Figures 9 and 10). Teachers in all jurisdictions also prefer innovative pedagogy over traditional pedagogy (Figure 11). Overall, teachers strongly prefer holistic education that prioritizes student well-being.

FIGURE 9

FIGURE 10

FIGURE 11

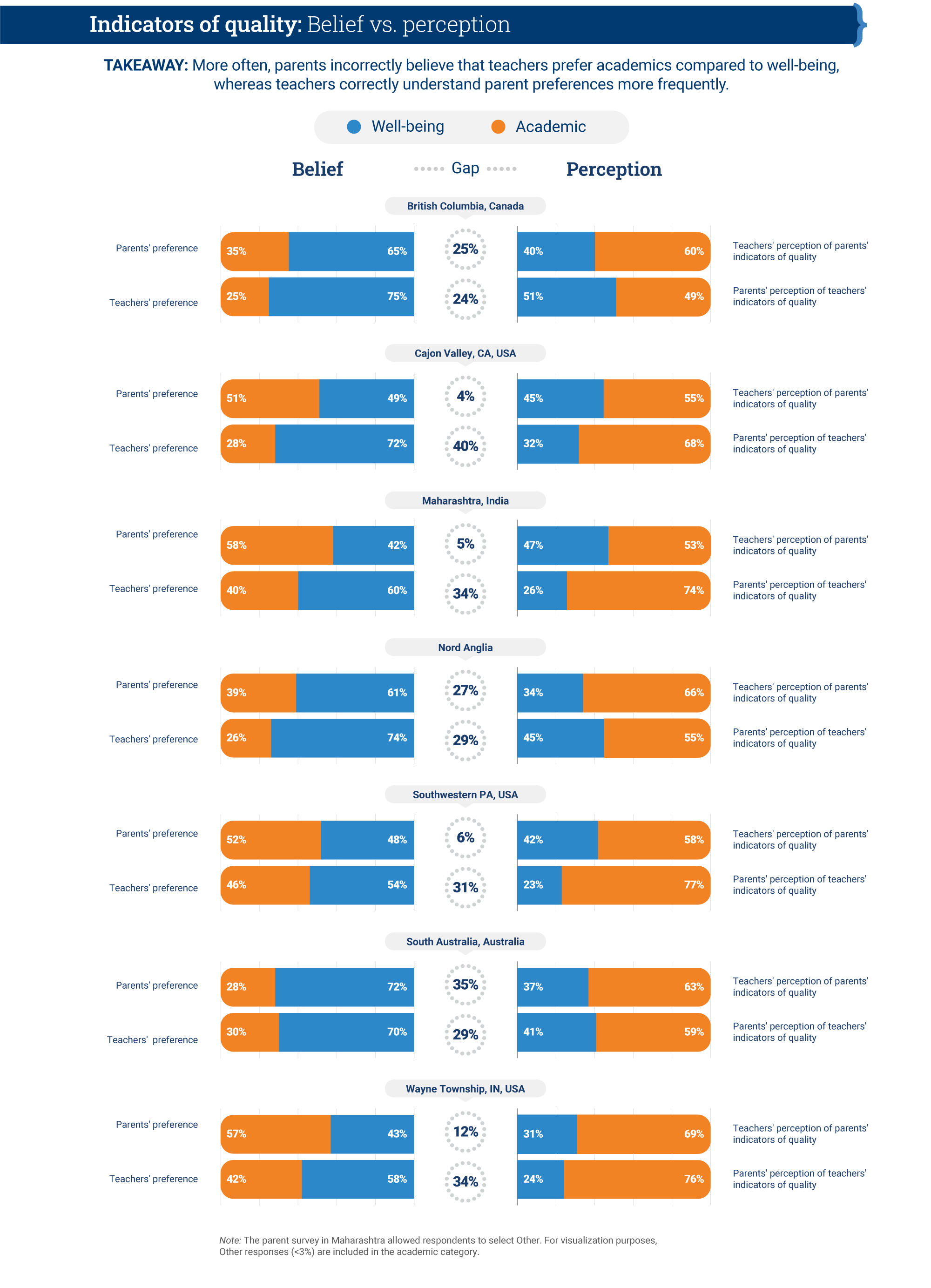

Parents and teachers however have very different perceptions of each other’s beliefs about school. Perhaps most striking are their perceptions regarding what makes for a good school experience: the academic indicators of quality versus the well-being indicators (Figure 12). While most teachers in every jurisdiction feel that the well-being indicators are most important, in every jurisdiction they also feel that parents prioritize the academic indicators of quality. Clearly in some jurisdictions teachers believe parents want different things than they do. The truth is that although parents in several of the surveyed jurisdictions do prioritize academic indicators of quality, many are more focused on their children’s well-being, just like teachers. A similar dynamic affects what parents believe teachers think is most important. Across all jurisdictions except British Columbia, parents believe the academic indicators of quality are most important for teachers—virtually the opposite of what teachers say they prioritize.

When it comes to beliefs about the purpose of school, parents and teachers are no more accurate in perceiving each other’s beliefs. A comparison of responses about the most important purpose of school shows that what parents think about teachers’ beliefs is rarely similar to what teachers say their own beliefs are, and vice versa (Figure 13). In many jurisdictions, both groups perceive the other as being much more focused on the academic purpose of school than they really are.

FIGURE 12

FIGURE 13

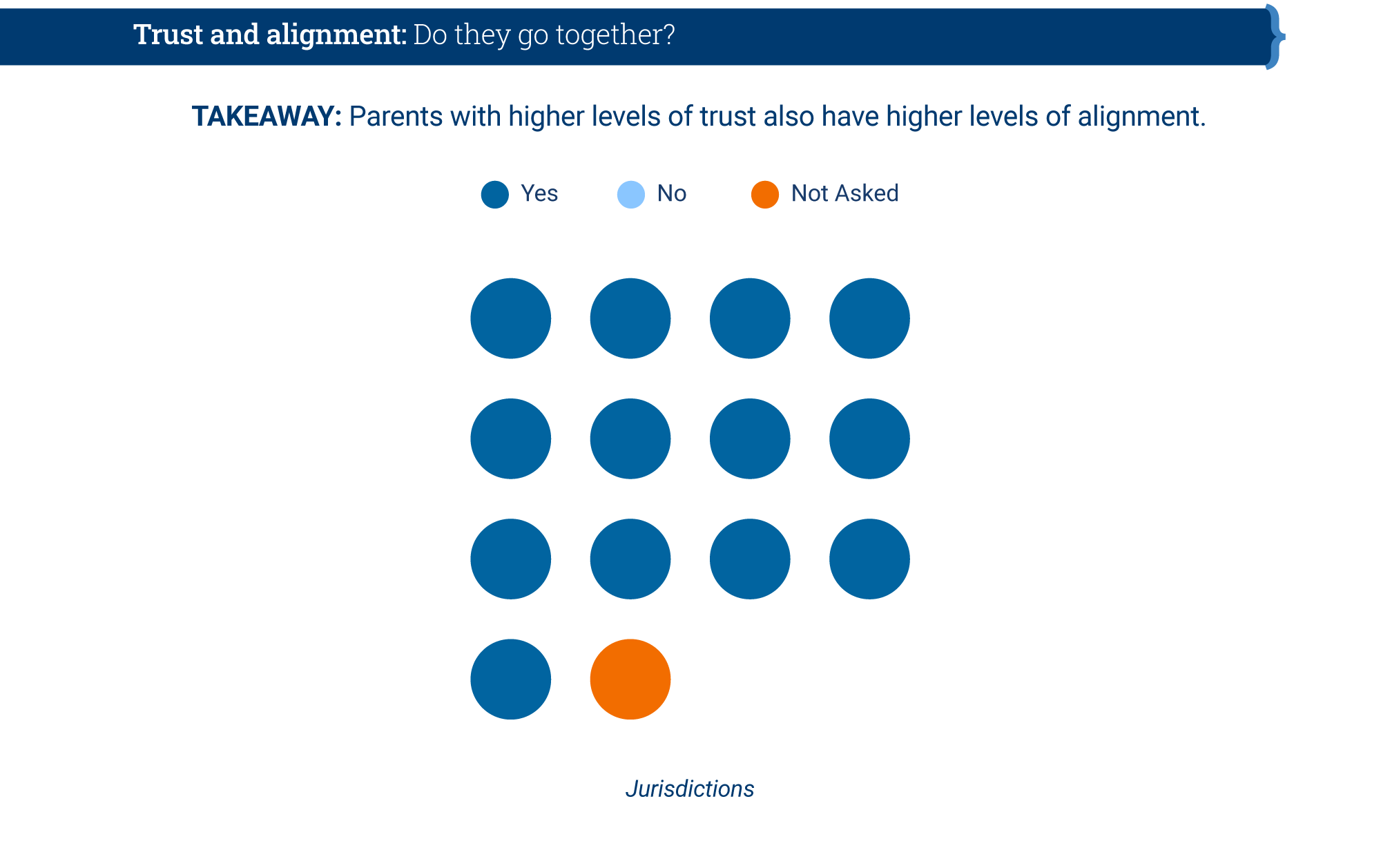

Insight No. 3: The more receptive teachers are to parents’ inputs, the more parents feel they share teachers’ beliefs about schooling

Across all jurisdictions, it is clear that parents who have higher levels of trust in their children’s teachers feel more aligned with them (Figure 14). Parents who feel that teachers are more receptive to their inputs (which we use as an indicator of trust) are more likely to feel that they share their teachers’ beliefs about what makes for good-quality education for their children (which we use as an indicator of alignment). Although (as seen above) this does not mean parents are accurately assessing what teachers believe, it does demonstrate how aligned they feel they are. This is a relationship that holds true in every jurisdiction. Conversely, it also means that parents who have lower trust in their children’s teachers are less likely to feel they share the teachers’ beliefs about school.

FIGURE 14

We do not know whether teachers’ receptivity to parents’ inputs leads parents to feel they are aligned in their beliefs about school or whether it is the other way around, with parents who feel they share teachers’ beliefs causing teachers to be more receptive to their input. Either way, this finding confirms the important role of trust discussed earlier and that has been well established in other studies (e.g., Bryk & Schneider, 2002; Henderson & Mapp, 2002; Tschannen-Moran, 2014). It is an important reminder to any school or jurisdiction leader who wishes to help develop a shared vision between families and schools on what a quality education looks like: building trust is an essential ingredient.

Interestingly, in about half the jurisdictions, parents who have higher levels of trust and alignment are also more likely to believe that teachers care more about students’ well-being than about academics. The exceptions are parents in India’s Himachal Pradesh state and in the Nord Anglia global network of private schools, who are more likely to have high levels of trust or alignment if they believe teachers care more about students’ academics than about well-being.

The idea that more-educated parents will feel that teachers are more receptive to their inputs and that they will be more likely to share teachers’ beliefs because of their familiarity with school does not seem to hold. In all but a few jurisdictions, parents’ own educational attainment appears to have limited influence on their levels of trust in or alignment with teachers. In fact, parents with lower education in four jurisdictions—South Australia; Colombia; India’s Maharashtra state; and Wayne Township, Indiana, in the United States—are more likely than their more highly educated peers to have higher trust or alignment with their children’s teachers. Instead, as we see below, it is the age of the parents’ child that influences their levels of trust and alignment with their child’s teacher (Figure 15).

FIGURE 15

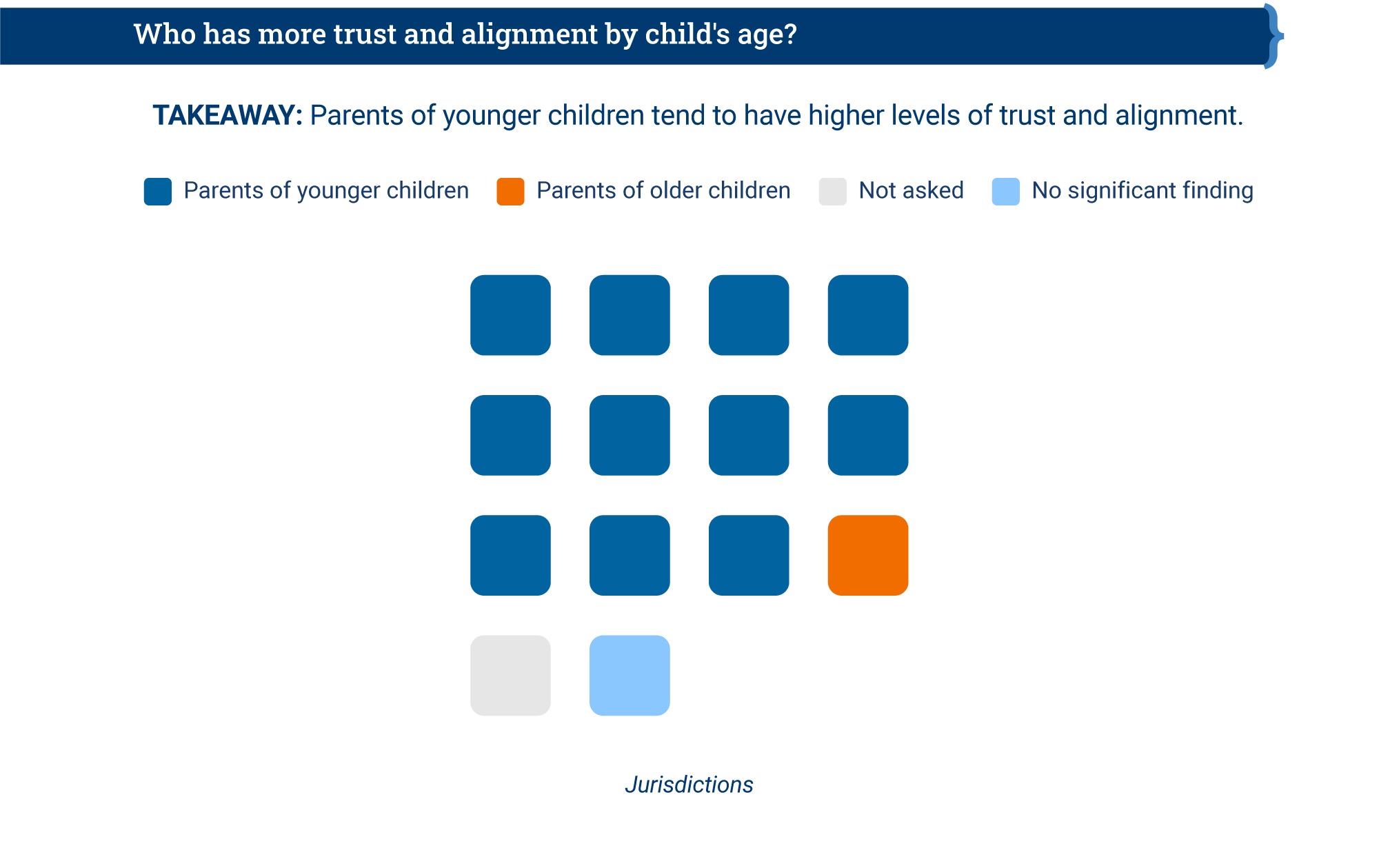

Insight No. 4: Parents’ beliefs about school are dynamic, changing greatly with their children’s age

A child’s age greatly influences the parent’s beliefs and perceptions about what indicates a quality school experience. This is a much more profound lens shaping parents’ views than their level of education, which in a few jurisdictions does appear to influence their responses to a few survey questions but not nearly to the extent that their children’s ages do. By and large, in all but three of the jurisdictions, parents of younger children are more satisfied with their education when they see indicators of the child’s well-being, whereas parents of older children focus more on success on the academic indicators.

In nine of the 14 jurisdictions, children’s age also shape parents’ preferences on the most important purpose of school, with parents of older children preferring the academic and/or economic purposes of school. As for the style of pedagogy, however, except in Buenos Aires, the age of parents’ children has no influence on their preference for innovative or traditional pedagogy.

Interestingly, parents’ level of education, a good indicator of their socio-economic status, is much less influential on their beliefs about school. When assessing the quality of their children’s schools, in six of the jurisdictions, parents with higher education are more likely to be satisfied when their child shows indicators of well-being, and parents with lower education are more likely to prefer seeing their child’s success on the academic indicators. However, parents’ education has little influence over their preference for innovative or traditional pedagogical approaches, except in contexts such as Buenos Aires and Himachal Pradesh, where parents with higher education are more likely to prefer innovative pedagogy.

As for parents’ views about the most important purpose of school, their level of education has a limited but mixed influence. For example, in Colombia, Ghana, and South Africa, the more highly educated parents are more likely to prefer the socio-emotional or economic purposes of schools. However, in southwestern Pennsylvania, the more highly educated parents are more likely to prefer the civic purpose of school. And in Maharashtra, parents with less education are more likely to prefer the academic purpose of school.

I hear that school is their [students’] preparation for the future. However, at least it should prepare them for the present, for in the present they are living with their classmates—solving their problems.

Parent, Argentina

As with parents’ beliefs about school, it is the age of children and not parents’ level of education that appears, across jurisdictions, to most frequently influence parents’ levels of trust in and alignment with their children’s teachers. In all but one jurisdiction, Himachal Pradesh, it is the parents of younger children who are more likely to say their children’s teachers are receptive to their inputs and share their beliefs about what makes a good-quality education. Interestingly, in Himachal Pradesh, where parents are more focused on academic indicators of quality, it is parents of older children who feel higher levels of trust and alignment with their child’s teachers.

Insight No. 5: The shapers of parents’ beliefs about education vary greatly by the parents’ own education level

Parents turn to many people and places for advice and guidance on their children’s education—primarily their own children. Parents around the world, through focus group discussions, told us how important observing and talking with their children is to parents’ assessment of the school. Beyond their children, though, who and what shapes parents’ beliefs?

Across many jurisdictions, we found that parents’ own level of education heavily influences who they say is most influential in shaping their beliefs about education (Figure 16). In nine jurisdictions, less-educated parents are more likely to be influenced by people in their everyday lives—whom we term “close” sources of information. A close source could be their child’s teacher, their local religious leader or other community leader, or other parents in their community. However, more highly educated parents are more likely to be influenced by people outside of their local community—or “far” sources—such as university admissions officers, academics studying education, and journalists or others in the media.

FIGURE 16

In some places, such as Buenos Aires and South Africa, the less-educated parents are more likely to be influenced by people in their community who are not part of the education system, such as local community leaders instead of teachers. The more highly educated parents are more likely to listen to experts outside their community but who are part of the education profession such as admissions officers and education researchers.

Parents’ level of trust also influences whom they turn to. Generally, across multiple jurisdictions, parents with higher trust levels are more likely to listen to people in their daily lives who are in the education system, whereas those with lower trust levels are more likely to listen to people outside of their community who are not part of the education system such as those working in the media.

Interestingly, the age of parents’ children has very limited influence across the jurisdictions on whom parents listen to. In a few jurisdictions (such as southwestern Pennsylvania, British Columbia, and the Nord Anglia locations), parents of younger children are more likely to be influenced by sources of information in their community, like teachers, and parents with older children are more likely to be influenced by people outside the community, like researchers.