CHAPTER 4

SERVICES

The importance and potential role of services in North American supply chains

Imagine you are a manufacturing firm in the United States considering locating a stage of your manufacturing process in Mexico. What is the full set of activities you would need to provide or procure to ensure that the operation in Mexico successfully integrates with your operations in the U.S.?

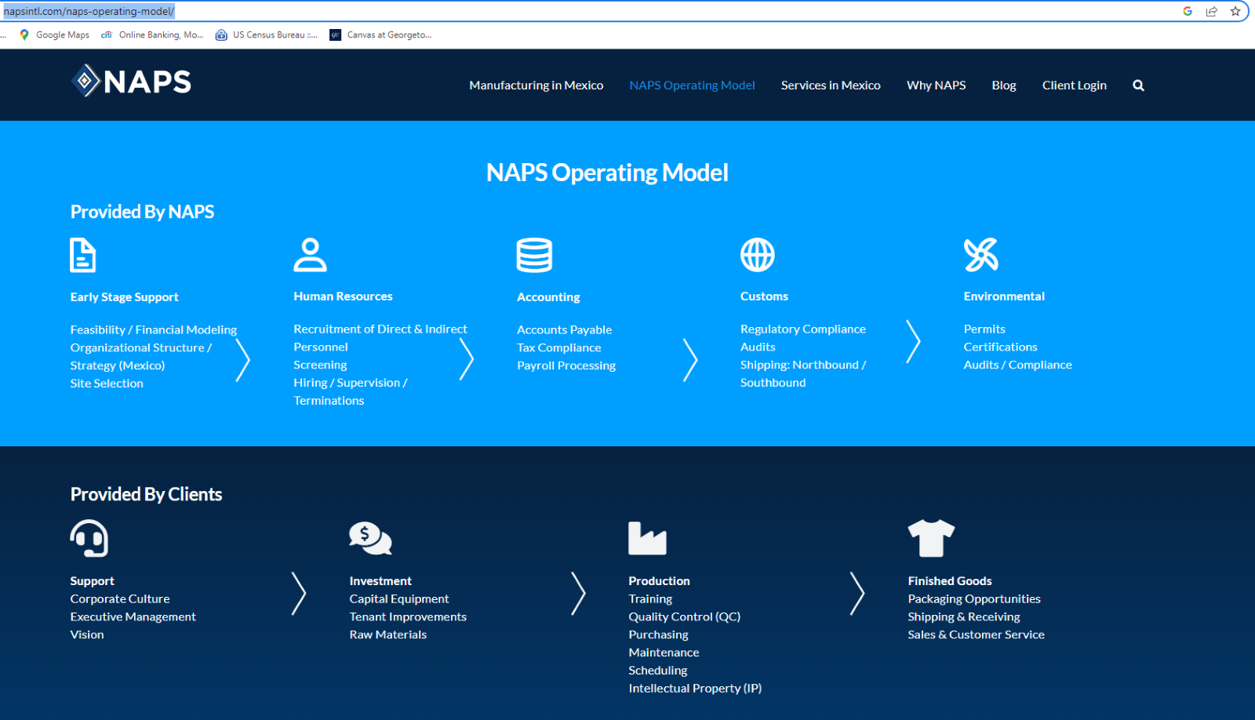

One approach to answering this question would be to work with a firm that specializes in helping American firms relocate production to Mexico. As an example, you could work with North American Production Sharing, Inc. (NAPS), a firm headquartered in southern California. The figure below, taken from the NAPS website, shows a number of considerations and inputs to successfully source from Mexico. The figure lists a number of services NAPS provides, including feasibility study, financial modeling, organizational structure and strategy development, site selection, human resources management, accounting, tax compliance, regulatory compliance, customs management, shipping and logistics, and environmental regulation compliance. A firm would also need to provide corporate culture, executive management, product designs and intellectual property (patents and trade secrets), process design and technology, research and development (R&D), marketing, distribution, and after-sales servicing. The list of important inputs provided by NAPS and a firm make clear that successful manufacturing production in a foreign country requires a significant number of business and professional services.

There is growing recognition among policymakers that (business) services are crucial inputs into global value chains.1 Business services like R&D, engineering, design, and marketing are key differentiators for firms’ products and services. Other business services like logistics, telecommunications, insurance, and finance enable firms to connect their global value chains and produce where it is most efficient. Business services are crucial inputs into global value chains, so the availability of low-cost, high-quality business services is essential for regions to successfully join global value chains.

In this brief, we assess the current state of business services in North America and explore the role of the USMCA in enabling business services to support value chains in North America.

What are business services?

We will use North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) industry codes that begin with “5” as our definition of business services. Below is a list of business service sectors with a brief description of the sector:

- 51 Information: The main components of this sector are motion picture and sound recording industries; publishing industries, including software publishing; broadcasting and content providers; telecommunications industries; computing infrastructure providers, data processing, web hosting, and related services; and web search portals, libraries, archives, and other information services.

- 52 Finance and Insurance: The Finance and Insurance sector comprises establishments primarily engaged in financial transactions (e.g., transactions involving the creation, liquidation, or change in ownership of financial assets) and/or in facilitating financial transactions. Three principal types of activities are identified: 1) Raising funds by taking deposits and/or issuing securities and, in the process, incurring liabilities; 2) Pooling of risk by underwriting insurance and annuities; and 3) Providing specialized services facilitating or supporting financial intermediation, insurance, and employee benefit programs.

- 53 Real Estate and Rental and Leasing: The major portion of this sector comprises establishments that rent, lease, or otherwise allow the use of their own assets by others. The assets may be tangible, as is the case of real estate and equipment, or intangible, as is the case with patents and trademarks.

- 54 Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services: Activities performed include legal advice and representation (accounting, bookkeeping, and payroll services), architectural, engineering, specialized design services, computer services, consulting services, research services, advertising services, photographic services, translation and interpretation services, veterinary services, and other professional, scientific, and technical services.

- 55 Management of Companies and Enterprises: The Management of Companies and Enterprises sector comprises: 1) Establishments that hold the securities of (or other equity interests in) companies and enterprises for the purpose of owning a controlling interest or influencing management decisions or (2) Establishments (except government establishments) that administer, oversee, and manage establishments of the company or enterprise and that normally undertake the strategic or organizational planning and decisionmaking role of the company or enterprise.

- 56 Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services: The establishments in this sector specialize in one or more of these support activities and provide these services to clients in a variety of industries and, in some cases, to households. Activities performed include office administration, hiring and placing of personnel, document preparation and similar clerical services, solicitation, collection, security and surveillance services, cleaning, and waste disposal services.

Business services are crucial intermediate inputs to business

Business services are important intermediate inputs into the production of many goods and services. Miroudot and Cadestin (2017) examine supply chains in a number of OECD countries and report “manufacturing companies increasingly produce and export services either as complements or substitutes to the goods they sell. This shift to services is related to strategies aiming at adding more value and creating a long-term relationship with customers. The report highlights that services inputs, whether domestic or foreign, account for about 37% of the value of manufacturing exports in the sample of countries covered. By adding service activities within manufacturing firms, this share increases to 53% and the overall contribution of services to exports is close to two-thirds. Across countries, between 25% and 60% of employment in manufacturing firms is found in service support functions such as R&D, engineering, transport, logistics, distribution, marketing, sales, after-sale services, IT, management and back-office support.” Business services, whether produced within the firm or purchased from suppliers, are increasingly important inputs to manufacturing products and, presumably, services.

Services inputs, whether domestic or foreign, account for about 37% of the value of manufacturing exports in the sample of countries covered.

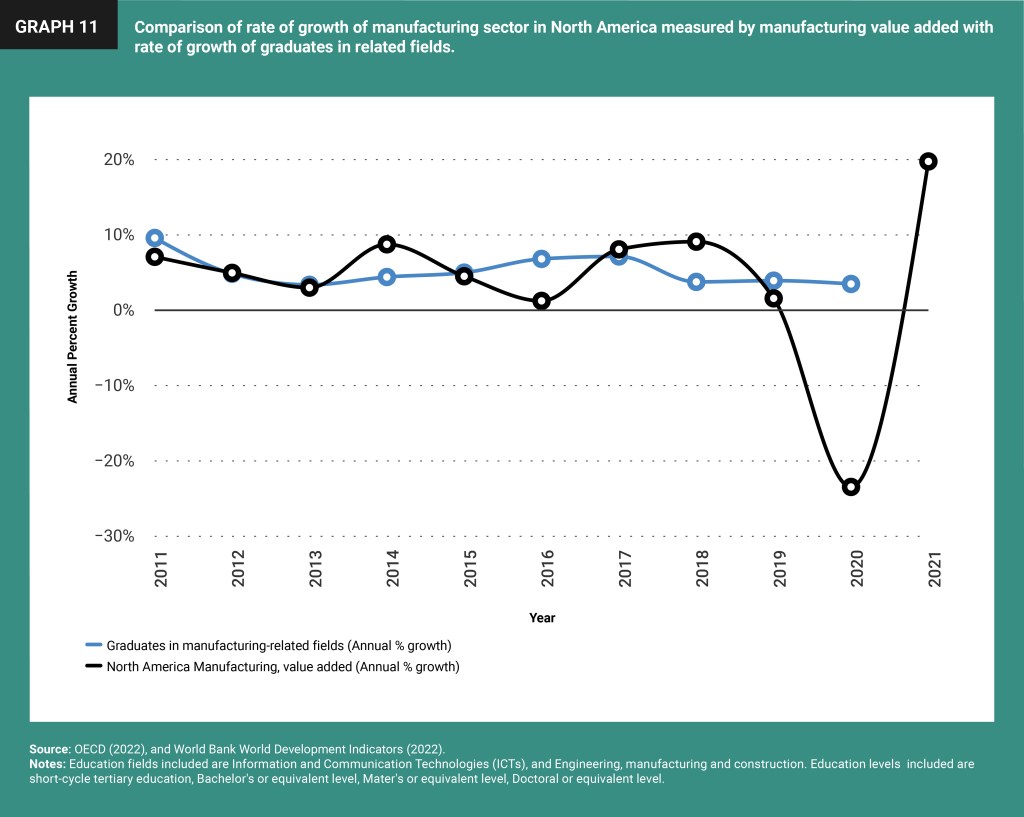

There is growing recognition among policymakers that fostering a robust and efficient business service sector is an important prerequisite for successfully joining and upgrading within global value chains.2 A key fundamental factor in the prospects for a robust business service sector are the availability of skilled workers.

Skill intensity of business services

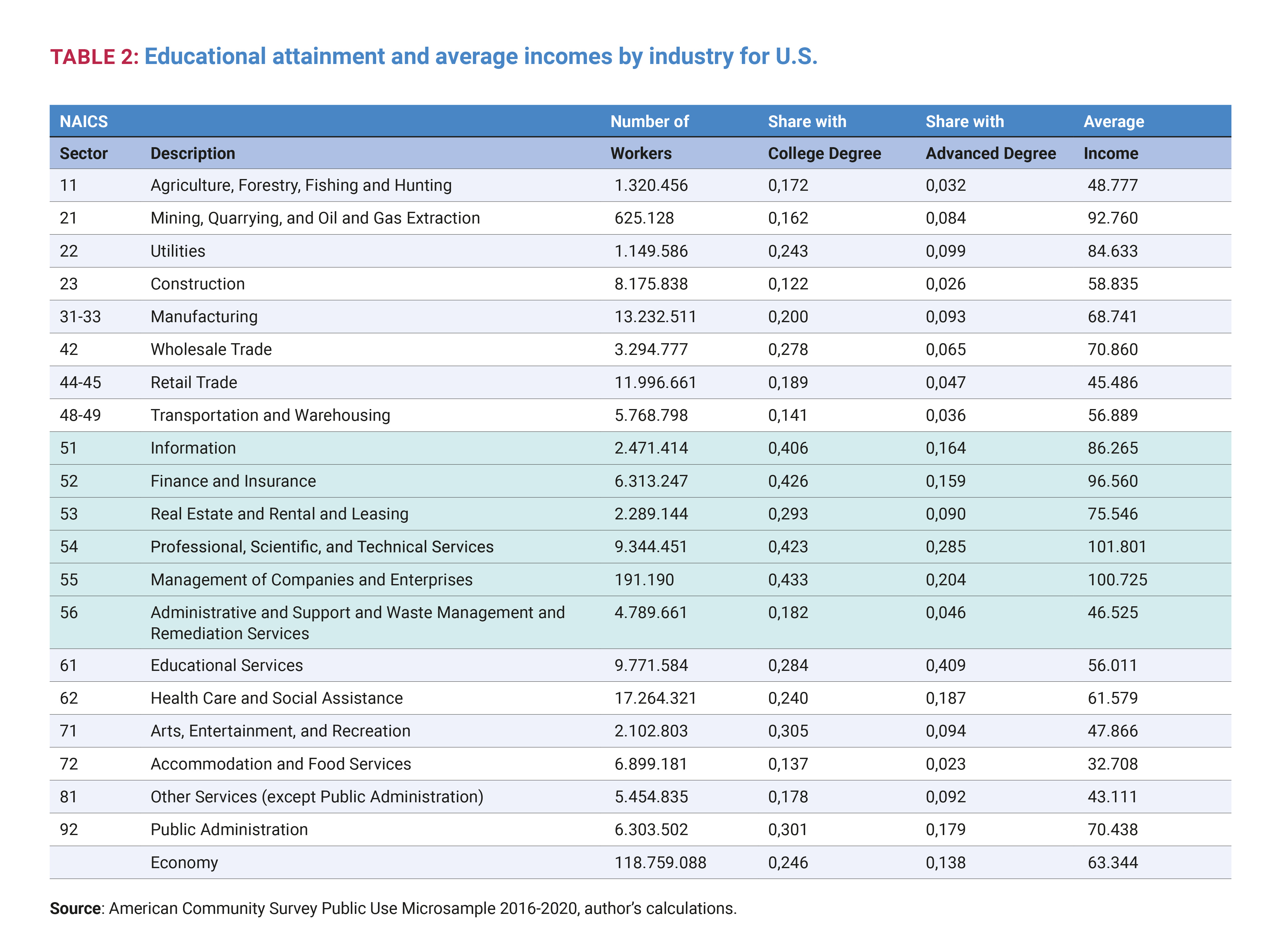

Business services are significantly more skill-intensive than other sectors. As a measure of the skill intensity of business services, Table 2 below reports the share of workers with only a college degree and the share of workers with an advanced degree across sectors in the U.S. The economy-wide average share of workers with a college degree is 25 percent and the share with an advanced degree is 14 percent. Table 1 reports that for business service sectors, that share of workers with a college degree is typically significantly higher than 25 percent. For example, in the Information sector, over 40 percent of workers have a college degree and more than 16 percent have an advanced degree. In Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services, the shares are even larger–42 percent and 29 percent respectively.

One potential impediment to establishing a robust and efficient business service sector in a country is the availability of educated workers.

Educational attainment

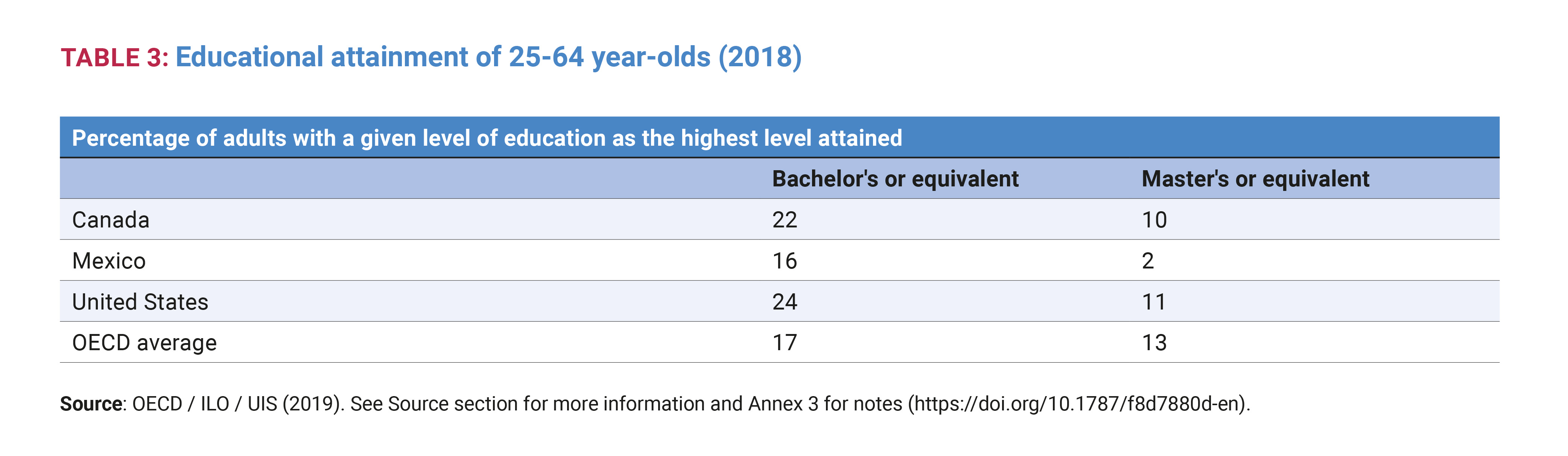

Business services are skilled worker intensive and thus require a supply of college educated workers. Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. have different endowments of college workers and advanced degrees. Table 3 below shows the share of workers in each country with a college degree and an advanced degree. Mexico has lower shares of both college educated workers and advanced degree holders suggesting that Mexico has fewer skilled workers relative to the overall labor force than either Canada or the U.S. The lower availability of skilled workers will make it more difficult for Mexico to produce business services.

Business services in Canada, Mexico, and the US

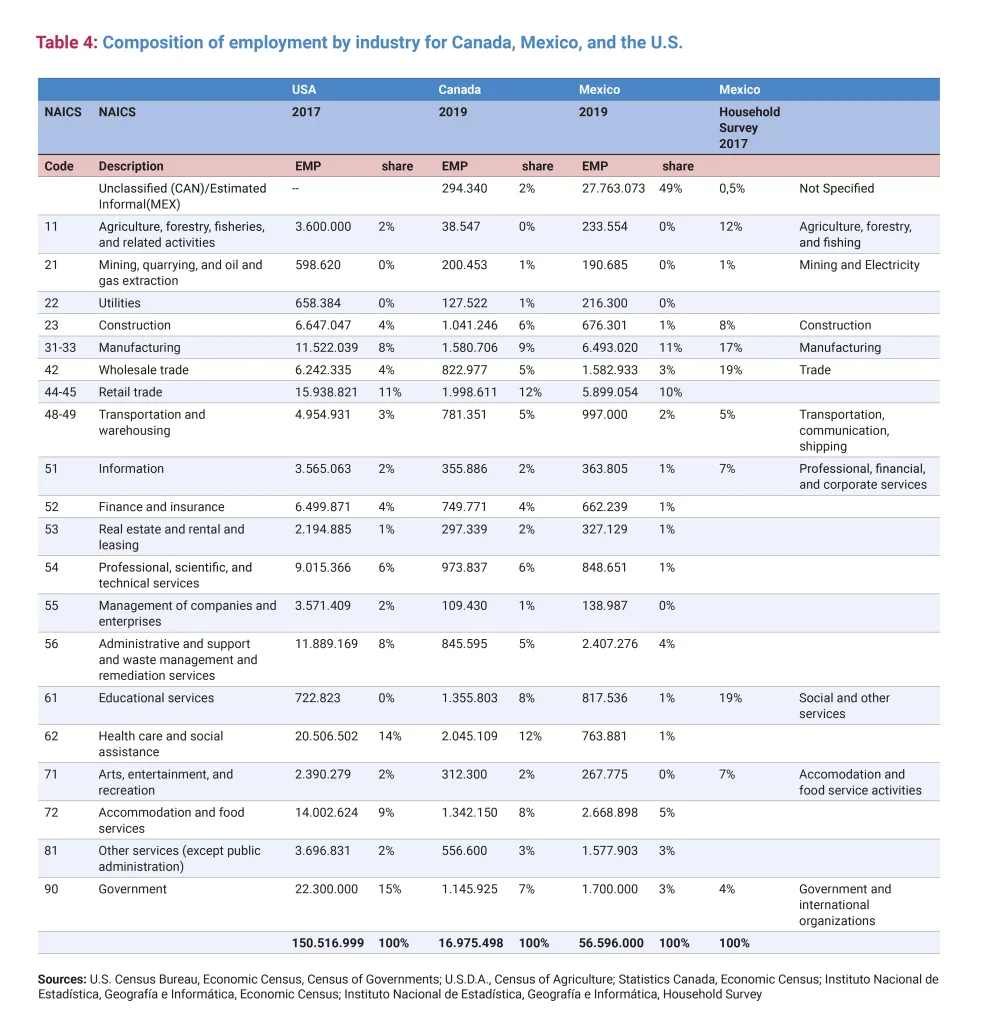

Given the relative scarcity of college educated workers and workers with an advanced degree, it is likely that Mexico will have difficulty producing business services. Table 4 below shows that relative size, in terms of employment, of the business service sector in each of the USMCA countries.3

The business service sector in Mexico is significantly smaller than the business service sectors in Canada and the U.S. For example, business services (NAICS industries 51-56) overall account for 24 percent of employment in the U.S., 20 percent in Canada, and roughly 8 percent in Mexico. Professional, scientific, and technical services, which include things like architectural, engineering, specialized design services, computer services, consulting services, research services, and advertising services and are important inputs into modern supply chains, account for 6 percent of the labor force in the U.S. and only 1 percent of the labor force in Mexico–the professional, scientific, and technical services sector is six times larger (relative to the size of the economy) in the U.S. than in Mexico.

Business services are important inputs to value chains (and development in general), and the business service sector in Mexico is relatively small–likely due to lower educational attainment in Mexico. One way for Mexico to “make up” for the relatively small business service sector is to import business services from the U.S. and Canada—suggesting an opportunity for mutually beneficial trade in services in North America.

Trade in business services

When economists think about what trade levels “should be” between two countries, they often think about the “gravity model” which suggests that trade flows should be a function of the size of the economies involved and the distance between them. Because both Canada and Mexico share a border with the U.S., we can think of the distance between Canada and Mexico and the U.S. as being equal.4 So, the size of each country’s economy should have an important influence on the trade flows between the countries. Here, we will focus on flows between the U.S. and each country.

Canadian GDP is about $2 trillion and Mexico’s GDP is $1.3 trillion. Interestingly, goods trade between Canada and the U.S. and Mexico and the U.S. are similar orders of magnitude for both imports and exports.5 The U.S. exports about $213 billion in goods to Mexico and about $255 billion to Canada. The U.S. imports about $330 billion in goods from Mexico and about $285 billion from Canada.

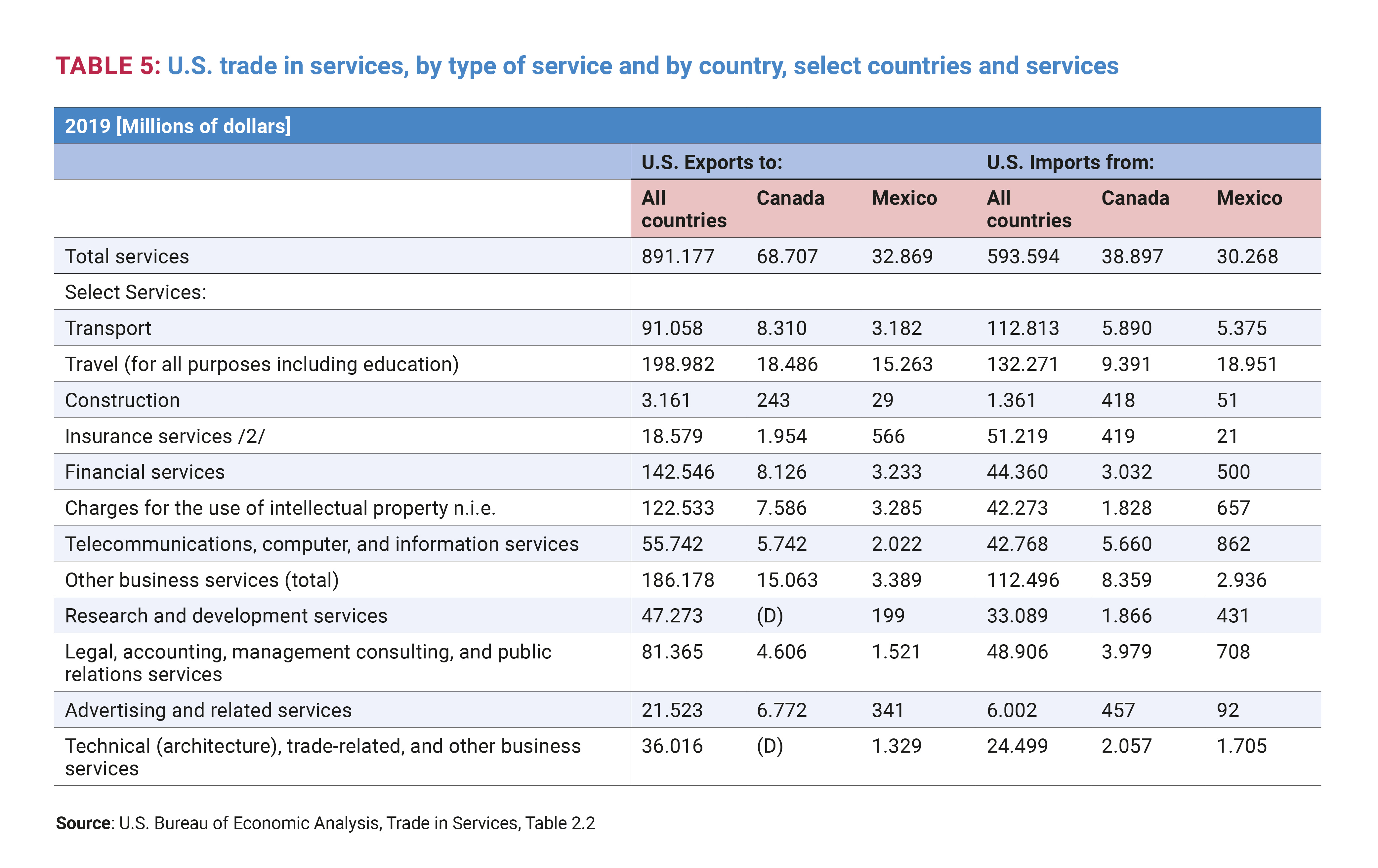

Table 5 reports total service trade flows between the U.S. and Canada and Mexico and the values of select service categories. In contrast to the rough equivalence in goods trade, U.S. services exports to Canada are about two times larger than its services exports to Mexico. In looking at more detailed business service categories (charges for intellectual property and information, computer, and telecommunications services), Canada’s imports are about double Mexico’s. For “other business services” (e.g., legal, accounting, management consulting, advertising, and R&D services), Canada’s imports are more than four times larger than Mexico’s imports. If we remove travel from U.S. service imports, U.S. service imports from Canada are more than two-and-a-half times as large as U.S. service imports from Mexico.

The lower level of U.S. non-travel related service imports from Mexico are not surprising given the skill-intensity of services and the lower educational attainment in Mexico (relative to Canada). However, the lower level of U.S. business service exports to Mexico is surprising given the smaller business service sector in Mexico.

Policy needs

While barriers to services trade are very difficult to quantify, most analysts believe that service barriers worldwide are much higher on average than tariffs on goods. NAFTA did have a fairly robust chapter on cross-border services trade which was an innovation at the time. However, NAFTA was negotiated before there was widespread internet usage. USMCA includes a new chapter on digital trade which prohibits the application of customs duties to digital products, ensures that data can be transferred across borders, prohibits data localization measures used to restrict where data can be stored and processed, protects against forced disclosure of proprietary computer source code and algorithms, and updated intellectual property protections.6 USMCA also includes a chapter on good regulatory practices which will hopefully lead to increasing alignment of regulatory standards and practices in the three countries.7

Business services are important inputs to value chains (and development in general), and the business service sector in Mexico is relatively small–likely due to lower educational attainment in Mexico. One way for Mexico to “make up” for the relatively small business service sector is to import business services from the U.S. and Canada—suggesting an opportunity for mutually beneficial trade in services in North America.

The more robust service sector provisions in USMCA are relatively new and might not have had enough time to fully influence behavior on the ground. Yet, it seems unlikely that the surprisingly low level of U.S. business service exports to Mexico relative to U.S. business service exports to Canada is due to trade policy impediments–the same trade policy rules apply in Canada and Mexico.

It seems possible that the low level of Mexican imports of business services is due to a kind of chicken-and-egg problem: Mexican products and services are not as sophisticated as U.S. or Canadian products and services (on average), which is likely due to a relative lack of (indigenous) business service capacity in Mexico (which is in turn due to the lower level of educational attainment in Mexico). Increasing the sophistication of Mexican production will require importing business services in the near term–which will likely increase the need to import business services.

The goal of developing efficient and globally competitive supply chains in North America is likely to require the use of more business services in production in Mexico. The goal of enabling Mexico’s continuing economic development and movement up the value chain is likely to require the use of more business services in production in Mexico. In the long term, increasing the availability and use of business services in production will likely depend on the ability of Mexican policymakers to increase educational attainment and training opportunities for Mexican workers. In the near term, increasing Mexican imports of Canadian or U.S. business services is one way to increase the availability of business services in Mexico (and fostering continuing economic development in Mexico). Additional research to identify specific ways to increase imports and use of business services in production in Mexico would be beneficial.

Endnotes

- 1. See for example Nayyar, Gaurav, Mary Hallward-Driemeier, and Elwyn Davies. 2021. At Your Service? The Promise of Services-Led Development. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648- 1671-0.

- 2. See for example, World Bank. 2020. World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1457-0 and Nayyar, Gaurav, Mary Hallward-Driemeier, and Elwyn Davies. 2021. At Your Service? The Promise of Services-Led Development. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648- 1671-0.

- 3. The informal sector in Mexico is quite large. Because the informal sector is not in scope for each country’s Economic Census, this makes it somewhat difficult to use comparable data from each country’s Economic Census data collected using the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS). I include an estimate of the informal sector in Mexico and (implicitly) assume that informal sector workers are unlikely to work in business service industries. As a reality check on the Economic Census data for Mexico, I also include estimates from INEGI’s Household survey of employment. The magnitude of the business service sector from the two different collection programs are of similar magnitude.

- 4. This is obviously a simplification as there are (different) distances between concentrations of economic activity in each country and each country’s border, but we will ignore those realities here.

- 5. See Graph 1 in “USMCA Forward 2022,” edited by Meltzer and Coulibaly, Brookings Institution.

- 6. One area where USMCA could have gone farther is supporting temporary entry for business persons. It has been reported that the U.S. sought new restrictions on the temporary entry of business persons into the U.S. and worked against efforts to expand and update the list of professionals eligible for temporary visas. See, for example, https://www.whitecase. com/insight-alert/overview-chapter-16-temporary-entry-us-mexico-canada-agreement. Allowing more Mexican professionals temporary entry into the U.S. would increase opportunities for knowledge transfer to Mexican professionals and would likely improve the capacity of Mexican firms to utilize U.S. (and Canadian) business services.

- 7. Achieving regulatory convergence is a desirable objective because domestic regulations can serve as impediments to services trade.

Viewpoints

Lourdes Melgar argues that Mexico’s inability to supply clean energy is putting at risk opportunities to revitalize its economy under USMCA.