The American

Dream Deferred

June 2018

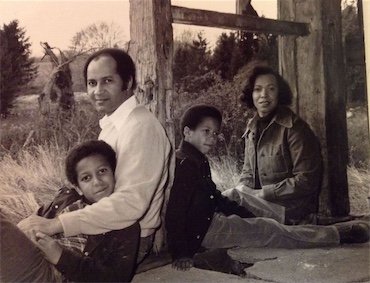

My father was born in the small, segregated mountain town of Hendersonville, North Carolina, in 1936. Less than 100 years before his birth, enslaved black Americans were building Hendersonville’s Main Street.

The son of a single mother, my dad grew up in poverty. When his mother became too ill to raise him, his grandmother stepped in until she too was no longer able to care for him, and then a local family took him in as their own.

With no source of financial support and no tradition of college in his family, my dad never considered going to college. But members of the local community, recognizing his potential, encouraged him to go. His church even sent around a collection plate to help pay his first semester’s tuition at North Carolina Central University.

Part-time jobs enabled him to work his way through school. When he graduated, he moved to Washington, D.C., where he was soon hired by IBM, becoming the company’s first black salesman in the Northern Virginia area. Before long, IBM identified my dad as one of its highest achieving salespeople globally, and promoted him to a job in its offices in New York.

When he and my mom were looking to move to the New York City suburbs, real estate agents’ illegal racial steering policies nearly kept them from buying the house they wanted in an all-white neighborhood in New Jersey. It took a sting operation coordinated by the local Fair Housing Council, in which a white couple posed as my parents, to help break the persistent segregation in the town where I would eventually grow up.

For my dad the road to success was anything but easy. But by the time I was born, he had moved his family from poverty to the middle class within the span of a single generation.

The broken bargain

My dad, who died in 2013 just six days before I was elected to the United States Senate, was kind, funny, and creative. He was also talented, hardworking, and intelligent. He achieved so much because of who he was. But he made it clear to me that he was only as successful as he was because of all the help he received along the way—from the family who took him in, to the folks in his church who insisted that he go to college and helped him do so, to the activists from the Fair Housing Council who fought for him. At a time when corporate America was even more homogenous than it is today, his ability to get his foot in the door as a black man at IBM was made possible by the fact that the local Urban League, an advocacy organization in Washington, D.C., and others helped him, championed him, and opened that door for him.

My dad’s life was an exceptional testimony to the way the bargain—that if you work hard, sacrifice, and struggle, you can make it—should work. But he knew his experience was just that—exceptional—and he was anguished by our country’s inability to extend the bargain he believed in to all of her people.

In the years before he passed away, my dad expressed concern to me that the bargain that had worked for him, the one he believed in, wasn’t becoming more real for more Americans, but instead moving further and further away.

In many ways, my dad was right. For millions of Americans—white and black, men and women, Latino and Asian, straight and LGBTQ, people from every walk of life and every religion—the barriers to opportunity and success are higher than ever.

The bargain—the one my dad and millions of other hardworking Americans made with America and that America kept with them—is broken.

A 50-50 shot

Newark, New Jersey, has been my home for more than two decades. For over seven of those years, I served as the city’s mayor.

When I was elected in 2006, my team and I were determined to make our city safer, more prosperous, and more successful than ever before. We prioritized public safety, and put reducing crime and violence at the center of our efforts. In 2008, our city went 43 days without a murder, the longest streak in 48 years. Four years into my administration in 2010, the city of Newark had its first calendar month without a murder since 1966.

We worked to jumpstart Newark’s economy. Billions of dollars in new investments came into Newark, and these projects created jobs for local residents. For the first time in 50 years new residential high-rises broke ground downtown, for the first time in 40 years a new hotel opened in our city’s downtown, and for the first time in 20 years the city had new office towers and major supermarkets being built. By the 2010 Census, Newark’s population had grown instead of shrunk for the first time in 60 years.

We recognized that Newark would never fulfill its potential as a city without activating the potential of its residents, so we pioneered innovative education solutions, a city parks and public space expansion, workforce and training programs, and reentry initiatives for residents returning from prison.

Along the way we addressed a major budget shortfall and made it through the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. Our goal at each step was to reimagine our city so that opportunity, safety, and security could be a birthright for all of our residents.

The Central Ward of Newark is my home to this day, and I am deeply proud to see the incredible work that continues in my neighborhood and my city, with its rich history and inspiring people. But when I come home after a week working in Washington, I am immediately struck by the urgency of the challenges we continue to face, and the work that remains.

Even as the dawn of the Great Recession recedes, the median annual income in my neighborhood, according to the last Census, was less than $14,000. To put that in perspective, average annual rent plus utilities for a 650-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment in Newark is $12,000 a year. Throw in groceries, transportation to and from work, childcare, medical care, and other basic necessities, and you can imagine how hard it is for a typical family in my neighborhood to get by.

Much like my dad, my neighbors are hardworking, committed, and intelligent. They want the best for their families and they put in long hours, sometimes at multiple jobs, in search of a better life. They are people like Natasha Laurel.

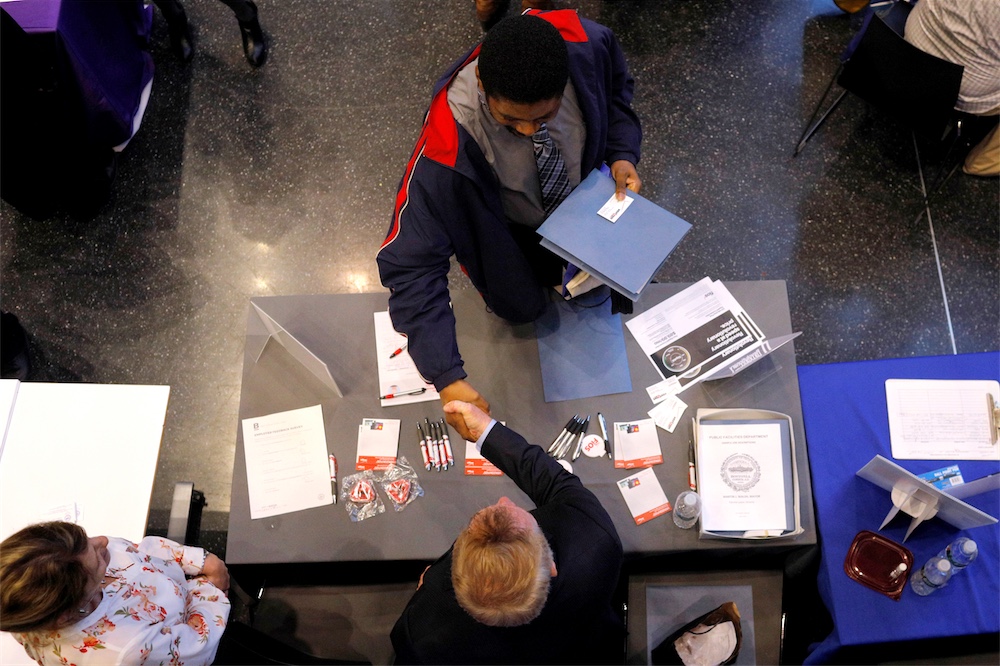

I first met Natasha in 2014 at the IHOP on Bergen Street in downtown Newark. It was the morning of Election Day and I was on the ballot. I was anxious, excited—and hungry. A few members of my staff and I sat down at a booth, and Natasha introduced herself as our server. Over the course of our meal, I learned a lot about Natasha. A proud mother of three boys, she was raising them on her own, and she dreamed of one day becoming a counselor, a job where she could do what she loved: helping people in need, advising and empowering them.

Today, just over 40 percent of all American workers make less than $15 an hour—the equivalent of $30,000 annually.

Natasha also told us how challenging it was to balance her work and family life, all while juggling her bills on a server’s minimum wage income of $2.13 an hour, plus tips. Her take-home pay was unpredictable, fluctuating depending on what shifts she worked and how busy the restaurant was. Each month she tried to set aside money for the things her sons needed, like wireless internet access so they could do their homework, and clothes that could keep up with their growing bodies. But even though Natasha worked full time, she and her sons lived precariously on the edge, relying on food stamps to put dinner on the table. Meanwhile, like millions of other Americans, Natasha didn’t have paid family leave to care for her son who was regularly hospitalized for asthma. So, she was forced to take on the added stress of paying her bills and caring for her child.

For Natasha, the bargain is broken. The price of everything—housing, childcare, and prescription drugs, to name just a few expenses—is going up. Spending per person on prescription drugs has risen by an average of 5.6 percent per year since 2000. And childcare in New Jersey is now more expensive than public college tuition, costing an average of $11,534 per year to provide care for an infant and $9,752 for a year’s tuition at an in-state, four-year public college. A May 2018 report from United Way found that close to half of American families cannot afford a basic monthly budget that includes food, rent, childcare, and health care.

Americans like Natasha are working harder and longer hours and yet wages aren’t keeping up. While my dad and so many of his generation were able to find a good-paying job that allowed them to bring their families into the middle class, most of my neighbors find themselves working harder and harder but falling further and further behind. And this experience isn’t unique to my city. Today, just over 40 percent of all American workers make less than $15 an hour—the equivalent of $30,000 annually. And close to half of all Americans would have to sell something or borrow from family and friends in order to meet an unexpected $400 expense.

And these inequities are compounded for Americans of color. Today, more than a decade since the Great Recession began, black Americans are the only racial group in America making less than they were in 2000. More than half of black workers are paid less than $15 an hour, and close to 60 percent of Latino workers make less than $15 an hour.

Meanwhile, someone growing up in my dad’s generation had a greater than 90 percent chance of earning more than his parents did. For young people born in the 1980s, just 50 percent will earn more than their parents. In the span of 40 years, we have become a nation in which, for half of our young people, the American Dream is falling out of reach.

Percent of children earning more at age 30 than their parents, by birth year

Wages are stuck

Corporate profits are soaring; in fact, they are at their highest levels as a percentage of GDP in more than 85 years, and the net worth of each of the 25 biggest American corporations ranks alongside or higher than the GDP of entire countries. The unemployment rate had declined to 3.8 percent by Spring 2018, a number that has traditionally led to widely felt economic gains as employers compete to attract and retain workers.

But the reality is less rosy. The so-called “U6” measure of unemployment, which measures not just the unemployed but also the under-employed—those who want to work full-time but can’t—is nearly twice as high as the standard unemployment rate, and is even higher for certain populations, like African-Americans and some in rural areas. In addition, wages and salaries for American workers, as a share of our GDP, are near the lowest they’ve been in more than 60 years. This is true despite the fact that worker productivity—output per hour—skyrocketed by 74 percent between 1973 and 2016. In return for this massive productivity boost, the typical American worker saw an inflation-adjusted increase in hourly pay of just 12.5 percent over that same 43-year period. If the minimum wage from 1968—50 years ago—kept up with inflation and worker productivity, it would be nearly $20 today.

Earlier this year, I met with a constituent whose job is to drive prepared meals from a kitchen to an airplane hangar for a major airline (an airline that enjoyed over one billion dollars in profits in 2017 alone). A 30-year veteran of the industry, he accepted a pay cut after the 9/11 attacks when airlines were tightening their belts. Since then he has barely seen a raise, and, nearing retirement, he makes less today than he did almost two decades ago in 2000.

Year by year and dollar by dollar, wage stagnation in communities like mine has chipped away at American workers’ well-being and upward mobility. The economic literature points to some of the reasons why: Technological advances in computing and other areas have advantaged highly skilled workers like engineers while leaving others behind—a phenomenon economists call “skill-biased technical change.” Automation has undoubtedly undermined or displaced many low- and middle-wage jobs, from secretarial work to accounting. And globalization has enabled businesses to shift to cheaper labor outside our borders, putting downward pressure on the wages of Americans whose jobs are under threat of displacement. In fact, today, the company that my dad worked for, IBM, has shifted more of its workforce to India than it has retained in the United States. Perhaps most dramatically, the steady decline of labor union participation and the attendant erosion of labor protections have led to a fundamental imbalance of power between workers and corporations.

But stagnant wages can also be traced directly to decisions and actions by corporations (like the airline my constituent works for), facilitated by careless—and at times purposefully negligent—policy. The result? American workers are often being shut out from participating in the gains they help create.

Labor productivity and hourly compensation 1947–2017

When corporate profits are at their highest levels in close to a century and worker productivity is at a 40-year high, but workers’ wages are the lowest they have been in over 60 years, the urgent question we need to ask, and answer, is why? And more important, how can we fix it?

Short-termism fails the test

The same year my dad was born, 1936, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was reelected to his second term as president. And it was during his second inaugural address that Roosevelt established a mandate for a nation emerging from the Great Depression: “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.” Today, at a time when income inequality is the greatest it has been in close to a century, this is a test we are very clearly failing.

Across industry and financial markets, a culture of “short-termism” pervades: firms are increasingly focused on delivering immediate value for shareholders over making long-term sound investments including in, especially, their workers. In a survey conducted more than a decade ago, almost 80 percent of chief financial officers at 400 of America’s largest public companies said they would sacrifice the firm’s longer-term economic value in order to meet quarterly earnings expectations. Since then, the Great Recession and a range of other developments in our economy have added further pressures pushing corporate executives to squeeze every last dollar out of their operations. This mindset prizes quick returns over lasting investments.

Illustrative of this trend is the massive wave of stock buybacks in which companies, desperate to please shareholders, purchase their own shares in order to reduce supply in the market and drive up their prices. Before 1982, buybacks were generally considered to be a form of market manipulation, but in the decades since, as a result of a change in federal policy, they have become a staple of corporate decisionmaking. According to the economist William Lazonick, between 2003 and 2012 companies on the S&P 500 dedicated 91 percent of their total net earnings to stock buybacks and corporate dividends. That left just 9 percent for raises for workers and other kinds of investment in the workforce, such as expanded training.

It hasn’t always been this way. Through the 1960s and 1970s, companies generally avoided buybacks and spent little more than a third of their net income on dividends. The retained earnings could be reinvested in a company in productive ways, such as capital projects, research and development, and employee pay and training. But particularly during the 1980s, the mindset of “maximizing shareholder value” came to dominate boardrooms across the country.

A growing number of activist shareholders are increasingly motivated by extracting short-term value rather than creating long-term returns. This is one reason why the average holding time for stocks has fallen from eight years in 1960 to eight months in 2016.

Before 1982, buybacks were generally considered to be a form of market manipulation, but in the decades since, as a result of a change in federal policy, they have become a staple of corporate decisionmaking.

Compounding the problem, CEO compensation is largely based on stock options and other bonuses. CEOs are therefore heavily incentivized to use buybacks to boost share price and, in turn, their take-home pay. This appears to be especially true when their companies are not doing as well as expected. A recent study out of the University of Illinois found that companies projected to narrowly miss market forecasts for their earnings per share are significantly more likely to buy back shares than companies that are projected to narrowly exceed their earnings-per-share forecasts.

Some highly successful business owners are also critical of the focus on the short term. Ron Shaich, who founded the restaurant chain Panera and guided it to extraordinary heights before selling it to a private company late last year, has said that the “greatest competitive advantage Panera had, the reason we produced these results we did, is because we could think long term. And the reason I took our company private is I'm increasingly worried about our ability to do that in a public market.” Indeed, over the past 20 years, private companies—unencumbered by activist shareholders and executive compensation packages based on stock performance—have spent twice as much as public companies on “economically productive” investments like worker training and R&D as a percentage of their overall revenue.

If there were any doubts about the effect of short-term pressures on corporate decisionmaking, take the recent case of American Airlines.

Last year, American announced, along with its $234 million in first-quarter net earnings, that it would give pay raises to its pilots and flight attendants. But American’s decision—an acknowledgment that paying its workers fairly is integral to its long-term success—was immediately derided by financial analysts. One analyst for Citigroup complained that “labor is being paid first again, shareholders get leftovers,” while Morgan Stanley downgraded American Airlines shares, going as far as to argue that it “establishes a worrying precedent, in our view, both for American and the industry.” In response to this market reaction, American Airlines’ shares lost more than 8 percent in market value—about $1.9 billion—over the next two days. The message from the financial sector to companies considering pay raises and other types of workforce investments was clear: don’t.

We’ve seen how, in only a matter of months, this shortsightedness has been accelerated. The passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in December 2017 brought a sudden infusion of cash for corporations through a massive corporate tax rate cut. How have companies used the savings they reaped? So far, major corporations have gone on a buying spree, announcing nearly $500 billion and counting for programs to repurchase their own shares, further fueled by corporate debt, while spending just $6.9 billion on bonuses and wage increases for their employees. In other words, for every $1 given to workers, shareholders stand to gain $69.

Consider the case of Dollar General, the rapidly expanding retail chain with more than 120,000 employees at approximately 14,000 stores who helped produce $1.25 billion in net income in 2016. Dollar General pays its frontline sales associates as low as roughly $8 an hour on average, but in 2016 the company spent $990 million on stock buybacks. And Dollar General is no anomaly. In early 2018, Cisco, the networking company, announced a $25 billion stock buyback program, and five top pharmaceutical companies recently announced a combined $45 billion in buyback plans, all while drug prices continue to skyrocket.

In 1963, just a couple of years before my dad started working there, IBM CEO Thomas J. Watson Jr. wrote this in his book, A Business and Its Beliefs: The Ideas That Helped Build IBM: “As businessmen, we think in terms of profits, but people continue to rank first.” Can today’s largest corporations still credibly say the same?

A workforce “broken into pieces”

The fervent focus on delivering short-term value to shareholders and meeting high-stakes quarterly earnings targets has driven many firms to fundamentally rethink their relationship with their employees.

Companies are increasingly turning to outsourcing, or “contracting out,” much of their workforce. As part of a no-stone-left-unturned effort to cut costs, companies contract out key business functions, auctioning them off to the lowest bidder. Rather than hiring employees directly, these firms increasingly rely on contractors, temp agencies, and franchises. The economist David Weil refers to this strategy as the “fissuring” of the workplace, because “the employment relationship has been broken into pieces.”

Workers at major hotel chains and airlines, the janitorial staff of major companies, and workers at major food service operators are less and less likely to be formal employees of the corporation they work for day to day. Instead, they are employed by a loose network of middlemen or independent contractors who each take a cut—at the employees’ expense. A study by the economists Larry Katz and Alan Krueger estimated that potentially all of the net job growth in the United States between 2005 and 2015 came from alternative work arrangements like temp agency workers, on-call workers, contract workers, and freelancers. Studies have found that outsourced and subcontracted workers’ wages suffer dramatically compared with their non-contracted peers. For example, contracted port trucking drivers make 30 percent less than their directly hired counterparts; for agricultural workers, it’s 40 percent less; and for fast food workers the difference can be as much as $6 an hour less than “direct hires.”

While contract workers and directly hired employees may share the same mission, purpose, and in many cases even the same uniforms, their experiences are widely divergent. Contract workers are monitored and controlled as closely as any direct employee, yet not only are they paid less, but at the hands of unscrupulous contractors they are often paid late even as they are forced to work in unsafe workplaces. And as workers overseen by some entity separate from the one they are servicing, their pathway for professional growth is virtually nonexistent. For many subcontracted workers at some of the country’s biggest companies, there is no corporate ladder, no moving up—just a very low ceiling. Forget about going from the mailroom to the boardroom. These workers are stuck.

Studies have found that outsourced and subcontracted workers' wages suffer dramatically compared with their non-contracted peers.

How common is this practice? Of the 20 largest global employers in 2017—a list that used to be dominated by companies like General Electric and Ford—five are now outsourcing and “workforce solutions” companies. And these five represent a growing trend. In 2000, there was just one.

In the airline industry, for example, this fissuring has created a workforce of what amounts to second-class workers. Between 1991 and 2015, the percentage of workers in air transport-related jobs who are employed by subcontractors and contractors has roughly doubled. Today, more often than not, the people who help airline travelers with their wheelchairs, prepare in-flight meals, clean the cabin after landing, and perform many other crucial functions aren’t actually employees of the airlines whose names are on their uniforms. Instead, they are employed by the contractor that managed to submit the lowest acceptable bid. The result: half of all subcontracted airline workers in the New York-New Jersey area rely on public assistance to get by, even though many work at least 40 hours a week. They are people like my constituent Carol Ruiz.

I’ve met with Carol several times over the last year. A mother of three, she works full-time at Newark Liberty International Airport as a subcontracted employee in support of several airlines.

Every day she wakes up at 3:30 a.m. and goes to an airline catering service, where she helps prepare the food carts that flight attendants push up and down the aisle. She organizes the napkins, creamers, sugar, and cups that go on the beverage cart, cleans the glasses and silverware, and meticulously keeps track of the champagne that goes on the carts for first class passengers. For the first six years of her time working at Gate Gourmet, Carol received a four cents an hour raise each year.

At the end of the week she takes home $345—barely enough to cover the fair-market rate for a modest two-bedroom rental in Newark. Meanwhile, airline CEO pay operates at several hundred times that scale. CEOs at nine publicly traded airlines received an average compensation of $7.8 million in 2016, and the highest earner took home $18.7 million.

Labor violations in subcontracting jobs like the one Carol does are rampant, but when they occur, major companies are able keep them at arm’s length. Before Carol and her colleagues unionized, she never had a steady shift, and she never received sick days, vacation days, or paid holidays—despite working for some of the highest-profile, most popular airlines in the country and the world. Unionizing helped Carol and her colleagues win basic workplace protections and a small raise—but it’s still not enough.

In a recent conversation Carol shared that her husband and children made the gut-wrenching decision to forgo health insurance—because they didn’t have enough money to insure all of them. They wanted Carol, who had been diagnosed with cancer and underwent chemotherapy a few years back, to be the one to have insurance, in case her cancer returned.

Together, Carol and her husband make about $700 a week—too much to qualify for public assistance programs, but too little to get by. Carol shared that her husband will often try to work overtime on Saturdays so they have a little more room in their budget for groceries, electric, rent, gas, and the medicine she needs to take. Carol’s daughter is currently in college. Inspired by her mother’s struggle with cancer, she is studying to become a nurse. Carol is currently looking for a part-time job in addition to her full-time work.

Concentrated power, concentrated profits

Rising corporate concentration tells another part of the story behind stagnant wages. Across the economy, the largest companies are taking over an ever greater share of the market—conducting mergers, acquiring other companies, and squeezing smaller competitors out. According to a 2016 study from the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College, the years between 1990 and 2013 saw the most sustained period of merger activity in American corporate history, with the concentration of corporate assets more than doubling during this period. The same study also found that the 100 largest companies in the United States now control one-fifth of all corporate assets. Another survey analyzed hundreds of U.S. industries and found that the top four companies in each industry expanded their share of revenues from 26 percent of the industry total in 1997 to 32 percent in 2012.

A growing body of evidence suggests that the spread of this corporate concentration throughout multiple industries—from agriculture and technology to retail—has helped create a labor market in which workers are unable to negotiate with employers to translate their productivity and value into the wages they deserve. Wages are going down as a result.

Corporate concentration in American agriculture, for example, has created what has come to resemble a feudal state, in which small family farmers are given the choice between competing with enormous corporations or working for them through increasingly one-sided contracts. In the poultry industry, just four companies now control 60 percent of the market. As a result, individual poultry farmers have been driven out of business, and are forced to take on the costs and risks of raising chickens for the parent company without any guarantee of fair compensation.

A study by José Azar, Ioana Marinescu, and Marshall Steinbaum shows the impact of concentration on workers’ wages in other fields. Using data from Careerbuilder.com, the largest online job board in the U.S., they found that the most concentrated markets saw a 15 to 25 percent decline in posted wages over those in less concentrated ones. Wages were significantly lower for occupations with fewer companies posting on the website than for occupations where many employers are looking—and competing—for workers.

Sign on the dotted line

Today, companies rely on a range of practices to keep workers from translating their hard work and increased productivity into better pay and terms of employment. One of the core issues that has arisen in recent years is “monopsony power,” whereby one or a handful of employers have become so dominant in their market or region that they can exercise enormous control not just over their workers’ wages and their terms of employment, but even over where they work. Corporations are increasingly exercising monopsony power through purposeful practices specifically aimed at weakening worker mobility and keeping a lid on wages.

Workers all across the country, and in a wide range of occupations—home health aides, seasonal workers, baristas, manicurists, janitors, cooks, cleaners, hotel employees, hair stylists, receptionists, mechanics, taxi drivers, and others—are being held back under the threat of restrictive covenants that limit their ability to change jobs and get ahead. That’s because non-compete clauses—agreements between employers and employees that were originally intended to protect trade secrets and hold on to workers with highly technical training—are increasingly being imposed on low-wage workers. But now the intent is not to protect trade secrets; rather it’s to keep wages low by giving corporations enormous leverage over their employees. Today, as many as 30 million American workers, or 18 percent of the labor force, are currently covered by a non-compete clause. One in seven workers making under $40,000 a year reports having signed one.

Sometimes, workers will sign non-compete clauses unknowingly. But more often they sign because they have to. A 2017 report found that of all employees asked to sign a non-compete clause, two-thirds reported they did so because they had no other job offers.

Jimmy John’s, the popular chain of sandwich stores, infamously included non-compete clauses in the contracts of its $8.15 per hour workers, preventing them from moving to higher-wage jobs with competitors. Though Jimmy John’s eventually stopped including these provisions in its hiring papers, non-compete provisions across industry remain pervasive. These clauses keep low-wage workers from pursuing better-paying jobs in the same fields. Data from the Census Bureau show that a worker who switches employers within the same state will see an average 7.6 percent in earnings growth over the course of a year than someone who stays in the same job.

The results of not abiding by the non-compete clause can be devastating. Keith Bollinger, a North Carolina factory worker who signed a non-compete clause, took a better paying job with another factory and was sued by his former employer. He later told The New York Times, “I tried to get a better life for my wife and my son, and it backfired. Now I’m in my mid-50s, and I’m ruined.” According to the Times, Mr. Bollinger lost his savings after having to engage in a three-year legal battle with his former employer.

Benny Almeida told The Seattle Times that when he accepted a $15-an-hour job cleaning up water damage for a franchise of ServiceMaster, a $3.4 billion corporation, he unknowingly signed a non-compete clause. When he found a similar job paying $18 an hour, he took it. He soon received a letter from ServiceMaster demanding that he quit his new job because he was in violation of the non-compete clause he had signed.

Reading Mr. Bollinger’s and Mr. Almeida’s stories, I knew I would have likely done the same thing if I were in their shoes. Who wouldn’t? Hard work, ambition, and success are values that we claim to hold in high esteem as Americans. Yet millions of workers across the country are punished for trying to get ahead by companies intent on keeping them down.

Then there are so-called “no-poaching agreements”—a twist on non-competes—that are also used to freeze the pay of low-wage workers. Unlike non-competes, these agreements are often forged between large corporate franchisors—like Jiffy Lube and Carl’s Jr.—and their franchisees, usually unbeknown to the worker. Such covenants prohibit the franchisees from recruiting and hiring away one another’s workers. This means, for example, that none of the thousands of Carl’s Jr. franchisees may hire an individual who is currently employed—or was recently employed—by any other Carl’s Jr. franchisee.

A worker who switches employers within the same state will see an average 7.6 percent in earnings growth over the course of a year than someone who stays in the same job.

No-poaching agreements prevent employees from finding higher-paying jobs at restaurants in the same chain. Even worse, the agreements limit employees’ leverage to negotiate for a raise because their current employer knows they are stuck, with no other restaurant in the franchise able to hire them.

This isn’t a niche issue. As of 2016, 58 percent of the country’s larger franchisors employed some form of no-poaching agreements. That includes IHOP, the 1,600-restaurant company that employs Natasha, my friend in Newark. For these workers, an already limited range of options narrows further.

And yet, we know it doesn’t have to be this way. There are companies, like Trader Joe’s and Costco, that are proving that investment in workers isn’t just good for workers, it’s also good for business. Extensive research by business professor Zeynep Ton has confirmed this, showing that many companies have found that making long-term investments in their workers is associated with more efficient operations, greater employee dedication, and lower turnover—ultimately leading to stronger profits and growth.

The path forward

What James Baldwin wrote decades ago is still a painful reality for millions of Americans: “Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.” When I talk with people living and working under the burden of economic insecurity, they almost always say that they are working as hard as they are, for as many grueling hours, not just for themselves, but for someone else—their children, their elderly parents who need their help, their families. For them, as for millions of Americans who are fighting every day for dignity and respect, their struggle will be worth it—their humble dreams will be realized—if they can help the next generation do better and have more opportunity. That was certainly my dad’s American Dream.

There is no reason that a country as rich and as powerful as ours should have to choose between great wealth for the few and great opportunity for all of its citizens. And yet we stand by as our economy reaches unimaginable heights of abundance while leaving so many working people behind.

The truth is that our economy works best when no one is left on the sidelines, and when American workers are able to fully participate in the economy they help drive. But that doesn’t happen by accident. We must find common cause in demanding an economy that restores for everyone the fundamental truths that defined my dad’s experience. We must work to be a country in which any American who wants to work can get a job; where if you work hard, you are paid what you are worth; and where a free market means freedom for workers to move across the labor market to translate their value and increasing productivity into higher wages.

Like Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society, we must reimagine what we can and should expect out of our government.

The right to a job

There is great dignity in work. My dad’s first job changed the course of his life, and mine. Anyone in this country who wants to work should be able to do so, in a job that pays a living wage and offers meaningful benefits. But we know that today, despite an official unemployment rate under 4 percent, millions sit on the sidelines or cannot find full-time work—a cause and symptom of increasing income inequality, labor market concentration, and continued employment discrimination. Americans across the country are working two or three jobs to make ends meet, and they should have the dignity of a job that pays them a living wage, gives them meaningful benefits like paid sick leave, and safe working conditions.

Both Martin Luther King Jr. and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt believed that every American had the right to a job and that government would see to it that every American who wants to work would be able to. A jobs guarantee invests in our nation’s greatest asset, our people, by getting them off the sidelines and into the labor force with a livable wage. And in addition to allowing unemployed and underemployed folks to fill critical roles in much needed areas like infrastructure and child care, a policy like this carries the potential of lifting everyone’s wages.

Say you’re a store clerk making $9 an hour at Dollar General, or my friend Natasha at IHOP. A jobs guarantee would allow participants to have real options with a public sector job. If Natasha was making $2.13 an hour plus tips, but then had the ability to get a job with living wage plus benefits and paid leave elsewhere, IHOP would have to change its behavior to attract workers like Natasha, and raise wages in order to compete in the new labor market. If they want to keep you, they need to be competitive.

This is an idea we can prove will work by creating a model federal jobs guarantee program and piloting it in up to 15 high-unemployment communities across the country. Not only would this have a positive impact on the lives of potentially hundreds of thousands of Americans right away, but the valuable data gathered would help us learn lessons, assess its effectiveness, and perfect the idea. We would be able to test it in rural and urban communities alike and conduct a rigorous evaluation to determine the impact on unemployment and wage growth, as well as on things like safety net spending, incarceration rates, and health outcomes.

A program like this would also help advance critical local and national priorities at a time when our infrastructure is crumbling, millions of families are struggling to find affordable child care, and communities are suffering from decades of disinvestment.

Workers in alternative work arrangements

Independent contractors, on-call, temporary help agency workers, and contract-firm workers

Hard work should pay off

Addressing wage stagnation and inequality seriously demands that Congress act to regulate and address the proliferation of corporate stock buybacks. Passing a law that says when companies buy back stocks to enrich shareholders and CEOs they should also pay out a commensurate sum to all of their employees shouldn’t be radical. When a company does well, it shouldn’t just be wealthy shareholders who reap the benefits. Under a law like this, the frontline sales associates of a company like Dollar General, who make as low as $8 an hour, could see a raise of roughly 30 percent.

We also need to do more to address the commoditization of workers through outsourcing. Take the airline industry, which receives billions of dollars from the federal government for flying its employees and assets around the world. Congress is in a position to exert pressure on it. I wrote the Airline Accountability Act with Senator Sherrod Brown to ensure that federal travel contracts with airlines are awarded contingent on compliance with labor law—not only by the airlines themselves but also by their contractors. Of course, outsourcing and the broader commoditization of workers extend well beyond the airline industry, to areas that include big tech, agriculture, and hospitality.

One way we can increase accountability for parent companies across the board is by codifying the “joint-employer standard,” which holds that if a company and its contractor share control over their workers’ terms of employment—how much they are paid, how they do their job, what they wear—then both firms should be held liable for obeying labor protection laws. Put forth in 2014 and under attack ever since, the standard is essential for establishing who workers are able to bargain with and for holding companies appropriately accountable for instances in which they share control over illegal working conditions.

During my time as mayor of Newark, we recognized that parts of our city, like so many others across the country, were struggling with low wages, high unemployment and lack of opportunity, and yet few investors were looking to these communities to inject their capital.

Today, more than 50 million Americans live in areas that are known as “economically distressed communities”—high poverty, high unemployment areas with few opportunities for job creation and little capital to jumpstart small businesses. In fact, according to data from the Economic Innovation Group, in more than half of “distressed” zip codes, the number of jobs and businesses declined from 2000 to 2015. When I came from Newark City Hall to the Senate, I knew that the programs we pioneered in Newark could work for other localities across the country as an economic development tool. I worked across the aisle and partnered with my colleague Senator Tim Scott on a bill that is based on the idea that every neighborhood should be a place of opportunity and investment.

We both knew that few private investors look to distressed communities when thinking about how and where to put capital. But by creating a framework for investors to drive capital into these communities through business accelerators or infrastructure development projects, and incentivizing long-term investments, we recognized we could move this money into the communities that needed it most. Research from EIG has shown that living in a “distressed” zip code has far-reaching and damaging implications, on everything from mortality rates, to health outcomes, to educational attainment. Their 2017 Distressed Community Index put this disturbing contract into stark terms: they found that Americans living in the average distressed county die close to five years sooner than their peers living in wealthier countries.

A free market means freedom for workers

“Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labour above their actual rate.”

—Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, 1776

We know that this isn’t the first time in our history we’ve seen large firms use their dominance to squeeze workers and suppliers.

Back at the turn of the 20th century, large “trusts” had risen to dominate many industries—in particular the nation’s railroad network and its oil production. Recognizing the danger posed by these trusts, Senator John Sherman of Ohio proposed an ambitious set of anti-monopoly laws. As he observed in 1889 when he introduced this legislation, a trust “can control the market, raise or lower prices as will best promote its selfish interests … break down competition … disregard the interest of the consumer … and command the price of labor.” To ensure that large-scale industry would remain competitive, Congress passed the antitrust legislation sponsored by Senator Sherman almost unanimously in 1890.

As a legal matter, these antitrust laws, still in place today, are meant to ensure competition for the benefit of both consumers and workers. But at some point in the years since, the government agencies in charge of enforcing these laws have forgotten about the part of their mandate that applies to labor. Instead of making sure that workers are protected when large companies merge, these agencies have ignored threats to competition in labor markets. And that’s been true for too long under both Democratic and Republican administrations.

We know that competitive markets promote economic efficiency and growth: they result in lower prices and better products for consumers, a level playing field for entrepreneurs and small businesses, and greater opportunities for workers. It is the job of antitrust regulators to protect competition across the economy—including in labor markets, to ensure that workers share in the wealth they help create. The Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission could address these shortcomings if they wanted to—and without action from Congress. The agencies should update their “Horizontal Merger Guidelines”— rules that help them determine whether a potential merger would have anticompetitive effects—to include the impact on labor markets, just as they do for product markets. In doing so, the federal government can ensure workers have meaningful choices that allow them to fairly bargain among potential employers. Such action is sorely needed: in an analysis of several decades of cases, my office was unable to identify a single instance in which the Justice Department or the Federal Trade Commission has challenged a proposed merger or acquisition due to labor market concerns.

When workers in any industry, for whatever reason, cannot translate their productivity into better jobs at higher pay, we are suffocating their—and our—potential. A free and fair economy is sustained by freedom and fairness for workers.

We know that bargaining power for workers matters. A 2018 Northwestern University study found that “the link between productivity growth and wage growth is stronger when labor markets are less concentrated.” In other words, workers are more likely to be paid a decent wage for the work they do when there are more employers competing for their labor. IBM invested in my dad all those years not just because it wanted to, but because the company had to; if he felt he wasn’t being compensated fairly for his value to the firm, he could have simply gone elsewhere.

We need to punish instances of collusion and wage fixing as proactively and aggressively as when these massive companies go after low-wage workers violating their non-compete clauses. To make this possible we should be significantly increasing the budgets of the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission; oversight doesn’t work if no one is watching.

The overuse of restrictive employment agreements like no-poaching clauses and non-compete agreements is an assault on the bedrock American principle of freedom of opportunity. This is why I introduced legislation to ban these kinds of agreements for low-income workers, to prohibit no-poaching clauses, and to allow workers to move freely across the labor market.

One in seven workers earning less than $40,000 per year is bound by a non-compete

Redeeming the dream

My brother and I grew up with an experience of the world that was drastically different than our dad’s. We were raised in a middle income, suburban community. Although we were virtually the only black family in town, we were met with love, care, and support from our neighbors and our community. We worked hard in school, in sports, and in our community and the bargain worked for us—we succeeded.

For my dad, I know watching his boys grow up with all of the blessings he could scarcely have dreamed of and that he had worked so hard for was a delicate balance of often conflicting ideas. My dad had an ability to, in the words of Walt Whitman, “contain multitudes.” He could hold in his heart and his head opposing feelings and ideas and find a way to balance the two. He knew that his two black boys could live and play freely in suburban New Jersey but that the same wasn’t true for so many other boys growing up in America. When I first got behind the wheel of a car as a teenager, my dad was proud, I’m sure, but I remember most clearly the very detailed and passionate instructions he and my mom relayed if I were to ever get stopped by police, which I did, much more than my white peers.

My dad, who had witnessed, been a part of, and benefited from the civil rights movement, knew that there was so much to be proud of as Americans, from our collective struggles for justice and equality, to our innovative spirit, to our collective compassion and care for one another. But he also knew the anguish of hate, cruelty, and evil that confronted too many fellow Americans.

My dad loved this country deeply. His faith in this nation was boundless, his hope for it unassailable. But he also possessed a deep and resounding anguish that this incredible nation had yet to extend the bargain he believed in to all of its people. My dad believed in the bargain, but he knew about the lie—that the promise of America wasn’t yet true for her people.

Almost five years have gone by since my dad passed away, and I think often about the contradictions of this nation that plagued him. I find myself balancing the same extraordinary love of America with the anguish and pain I feel knowing the blessings of this nation are still denied to too many of its citizens.

From cities like Newark to rural areas like the one my dad grew up in, Americans are trying—often on their own—to correct this imbalance, to bridge the gap between the ideals we cherish and the realities we must confront.

There is a way forward, a way through, and it starts with keeping the promise every generation of Americans in this country has made with the next: that we will give you a world better than the one we received. We have a lot of work to do to make this real and it must start with fixing, restoring, and expanding the bargain that working Americans have been making with this country for decades. It must mean restoring the value of work. It must mean a re-definition of our economic success not simply by the number of millionaires and billionaires we produce, but how we expand wealth, growth, and opportunity for all Americans. It must mean expanding the blessings of this nation so that the bargain works for every American who wants it.

To protect our promise, to restore our bargain, and to make real the truth of our most cherished ideals will require a renewed commitment. A renewed commitment to the big ideas that make people’s lives better, to pursuing the kinds of transformative policies that restore the value of work, and, most critically, a renewed commitment to one another.

It will require what Langston Hughes wrote when he said: “There is a dream in the land / With its back against the wall … To save the dream for one / It must be saved for all.”