At a hearing today before the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Health, Henry Aaron argues for retaining and improving the current Medicare program.

Mr. Chairman:

In my statement I shall emphasize the following points:

- Medicare has been an overwhelming success in providing access to care for groups that before its enactment had only limited access to insurance or standard health care. It is popular across the political spectrum. Polls reveal that people would rather raise taxes than cut its benefits.

- Neither part B nor D faces any problem insolvency. They are adequately funded in perpetuity under current law.

- The Part A trust fund is currently in better shape financially than it has been for most of its history. If all provisions of the Affordable Care Act are enforced, its financial gap is small.

- Many are concerned over Medicare’s long-term affordability. If provisions of the Affordable Care Act are enforced, the added budget costs of Medicare over the next quarter century are modest and affordable.

- Medicare has evolved in important ways, pioneering new payment systems that private plans then emulated. Under the Affordable Care Act, Medicare can continue to serve as a powerful instrument to effect systemwide payment and delivery reform.

- The concept of premium support dates from the mid-1990s (the concept of ‘vouchers’ is older). None of the plans now under discussion qualifies as ‘premium support.’ This is not a matter of semantics. Important policy elements distinguish current plans from premium support. Furthermore, none of the proposals to change Medicare have been specified in sufficient detail to let one know exactly what is being proposed.

- The conditions that recommended premium support in the mid-1990s no longer apply. The current Medicare program already fosters competition between publicly-administered, traditional Medicare and private plans. Current privately-administered plans raise costs.

- Changes to Medicare, implemented within the current framework, can save money and improve quality of care.

I.

Since its enactment in 1965, Medicare has been one of the most popular federal programs. It brings standard health care to the elderly and people with disabilities. Both groups lacked such access before Medicare was enacted. Medicare pools risks both across the population and through time. It spreads risks more effectively than does any private insurance pool. Despite criticisms of the program it remains popular.[1] By a margin of 70 percent to 25 percent, respondents say they want to keep Medicare as it is rather than replace it with an arrangement under which beneficiaries would be given money they could use to buy private or public coverage.[2]

- Support for the current program was strongest among self-identified Democrats.

- Support among self-identified Independents was nearly identical to the national average (71 percent to 24 percent).

- Self-identified Republicans also favored continuation of the current program by a 53 to 39 percent margin.

A Washington Post/ABC poll, reported in Politico last year, found that a 53-45 majority said that they would prefer raising taxes on all Americans to cutting Medicare. Seventy-two percent of respondents said they would favor raising taxes on those with incomes of $250,000 or more as part of a deficit reducing plan; only 21 percent said they would approve cuts in Medicare as part of a deficit-reducing plan.[3]

II.

There is widespread misunderstanding of Medicare’s finances. First, many confuse the trust funds with the budget. Second, many ignore the qualitative differences between the rules governing part A, Hospital Insurance, on the one hand, and those governing Supplemental Medical Insurance, parts B and D.

Part A is financed almost exclusively by earmarked taxes and interest earnings on reserves accumulated from past surpluses. Part A outlays can exceed revenues. Resulting deficits can deplete the trust fund. In contrast, parts B and D are financed by premiums and by general revenue payments that cover all program outlays not covered from other sources. Under current law, Parts B and D are fully financed in perpetuity. While it makes sense to talk of the solvency or insolvency of part A, it makes no sense to talk of solvency of parts B and D.

That said, all Medicare outlays are relevant to overall budget policy. Current concern about projected budget deficits is intense. It is important, therefore, to scrutinize total Medicare expenditures and consider how the program should be designed to use funds most effectively.

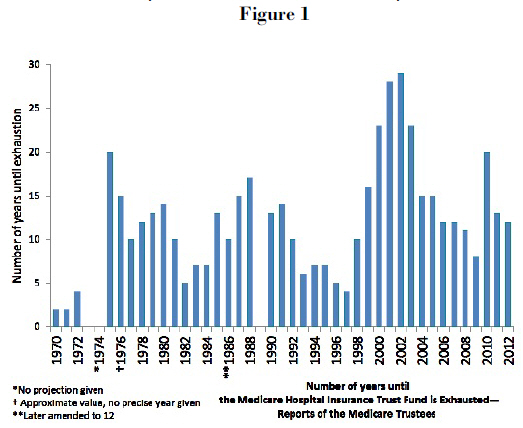

Solvency of Part A. The solvency of Hospital Insurance has been a topic of discussion, legislation, and controversy since Medicare was enacted. Each year, the Medicare trustees present estimates of the number of years remaining until the Part A trust fund will be exhausted under current law. Figure 1 reveals that projections of imminent insolvency are not new. For example, writing in 1999, National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare wrote:

“Without structural changes, the Medicare system will be bankrupt in 2010.”[4]

It didn’t happen. Nor has any other projection that the HI trust fund will be depleted been correct. The reason is quite simple. People like the program. Elected officials know that their constituents like the program. So, the elected officials have done what needs to be done to keep the program solvent. In the background is another fact—anticipating how fast health care spending will grow is difficult. In some cases, underlying trends have turned more favorable than assumed. Sometimes Congress has simply shifted part A activities to part B to be paid by general revenues. The bottom line is the same: Congress has acted to prevent insolvency. It has done so because the program is popular and highly beneficial.

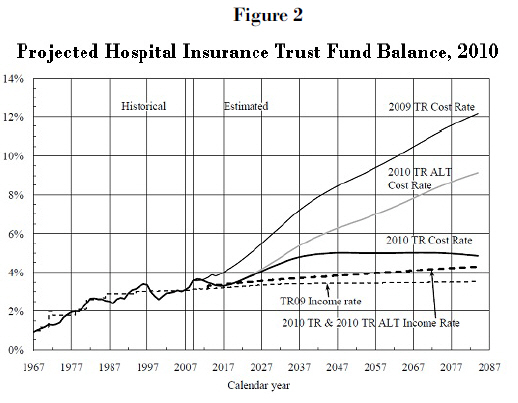

Figure 2 underscores the sensitivity of projections of balance in the part A trust fund to underlying assumptions.[5] Full enforcement of the provisions of the Affordable Care Act will greatly reduce the projected difference between earmarked revenues and projected outlays. As Figure 2 shows, the projected gap between cost and income was projected to be large and growing in 2009 before enactment of the Affordable Care Act. Full enforcement of the Affordable Care Act will reduce the gap and cause it to shrink over time. Many observers have expressed doubt that the targets in the Affordable Care Act can be enforced indefinitely. An expert panel, impaneled to review these targets, has yet to release their report. Through conversations with the chair and one panel member, I have learned that the group was divided on whether the spending targets can be sustained indefinitely but that the prevailing view was that they can be met for ten to twenty years. The United States now spends so much more for health care than other countries do that there is a large opportunity for reducing the growth of spending in the near term and to do so without rationing.

In summary, what figures 1 and 2 show is that to infer “unsustainability” from the fact that the Medicare trustees foresee a date when the trust fund is projected to run out of money if nothing is done is unjustified.

III.

While observers have documented many problems with the U.S. health care system, there is no evidence that Medicare performs less well than the rest of the health care system. In fact, for the last couple of decades, per enrollee Medicare spending has been growing at about the same rate or a bit more slowly than has per person health care spending for the general population. The United States faces a challenge to reduce waste and improve efficiency throughout its health care system. That challenge is no greater for services paid for by Medicare than it is for services paid for by private insurers, as all patients are cared for doctors and hospitals who care for Medicare and non-Medicare patients alike.

Over its history Medicare has pioneered reforms in health care payment. Prospective payment, a major cost-control innovation, was introduced in Medicare. Accountable care organizations, a promising innovation that can change incentives for the efficient delivery of care, will use Medicare to deliver those incentives. Bundled payments are widely regarded as a way to counter the excessive fragmentation of current health care delivery. While many problems have to be addressed before this reform can be carried to national scale, Medicare, as the largest single health care payer in the nation, could hasten the adoption of such reforms. The simple fact is that Medicare is a very large purchaser. With size comes clout—more clout than any private buyer has. To be sure, clout carries risks—by squeezing down payments, Medicare could simply force other payers to bear overhead costs. But clout also brings the capacity to shift incentives—and, if used wisely, to drive reform.

IV

For at least three decades some people from both parties have proposed replacing traditional Medicare with a single cash payment—a voucher. Beneficiaries would be able to use the voucher to help pay for insurance plans of their choice. Many people believed that choice among insurance plans was good in itself. They held this view despite overwhelming evidence that people care much more about choice of providers than they do about choice of insurance plans—and no private plan gives more choice among providers than Medicare does. In any case, the hope of voucher advocates was that insurers would compete for business based on cost and quality of service to customers.

The voucher idea gained momentum during the mid-1990s after failure of the Clinton administration’s health reform effort and as financial projections for Medicare Hospital Insurance deteriorated (see figure 1). With momentum came intensified scrutiny. That scrutiny identified serious risks from vouchers for the elderly and disabled. As a result, the term “voucher” acquired a rather nasty aura, which persists to this day.

Back in the mid 1990s, I shared both the hopes of those who believed that vouchers could generate significant savings and the fears of those who believed that vouchers would expose Medicare enrollees to dangerous risks. So did my Brookings colleague at the time, Bob Reischauer. As economists, we recognized the appeal of consumer choice. We understood the power of competition to police price and quality if market conditions were favorable. But we also believed that many of the plans then under consideration suffered from serious shortcomings. And we were convinced that whether voucher plans would have a chance of success depended on details—that place where the devil famously resides—to which few people were paying much attention.

So, we proposed three modifications to voucher plans that would minimize those risks.[6]

- The voucher plans then under discussion were mostly linked to indices, such as the consumer price index or nominal GDP, that had grown more slowly than health care spending and were expected to do so in the future. Such vouchers would systematically shift costs to Medicare beneficiaries even if growth of health costs did not slow. To be sure, linking vouchers to these indices would surely cut growth of Medicare spending. That would be good for the budget, but bad for Medicare beneficiaries. We believed that health care subsidies should be cut if plans fostered real economies, but not otherwise. Accordingly, we argued, that the voucher should be linked to general health costs. If competition boosted efficiency, enrollees and the taxpayer would both gain. But if competition didn’t boost efficiency, the first and overriding goal should be to protect the very vulnerable people who are enrolled in Medicare from increased financial burdens they could ill afford.

- The voucher plans then under discussion placed no limit on the number and variety of plans that insurers could offer. Few people have the capacity to evaluate the full range of provisions that insurance plans routinely contain. We believed that if consumers were to have a chance at all to choose rationally, the range of plans had to be limited to a modest number of prototype plans. Insurers should compete on service and cost, not by befuddling customers with variations that they could not evaluate.

- Health care cost for the Medicare population are high and concentrated. Accordingly, insurers have powerful incentives under standard voucher plans to compete based on risk selection. Such competition is costly and, in a plan that covers everyone, it is also socially pointless. We urged that direct sales by insurers should be banned. Instead, all insurance sales to the Medicare population should be carried out through a private nonprofit organization or a government agency, charged to provide objective information, advice, and counseling. We also said that no premium support plan should be considered until and unless a system of ‘risk adjustment’ was developed that was good to discourage insurers from competing via risk selection.

We christened a voucher plan that contained all three of these elements, including effective risk adjustment. We christened that system “premium support.” The term had not previously been used, but rapidly came into widespread use. The National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare adopted it three years later. So have others. The name, “premium support,” was and is often applied to plans that lacked one, two, or all three of the safeguards that we regarded as essential. My point, let me stress, is not a semantic quibble. The meanings of words in common use often change. But when a term is used in ways that obscure important policy distinctions, the misuse is harmful.

V

John Maynard Keynes is alleged to have quipped: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” As time passed, circumstances with respect to health care policy in general and Medicare policy in particular have changed. With those new facts, my views of premium support have also changed.

While I would not go so far as to argue that premium support should never be considered for Medicare, I believe that there are overwhelming and persuasive reasons why it should not be enacted now. I also have become less confident that premium support, even if it works for the rest of the population, would be desirable for Medicare. But it is too early to be sure. That said, I believe that there are several changes to Medicare that should be made promptly. These changes would lower costs, improve quality, and enhance fairness. I shall mention a few briefly in the next section of my testimony.

Improved Financial Prospects. The Affordable Care Act has significantly improved the financial prospects of the part A trust fund. Even with the increased cost estimates in the 2012 Trustees Report, the cumulative deficit over the next quarter century could be closed by a payroll tax increase of just 0.35 percent each on workers and employers. It could also be closed by changes in premiums, cost sharing or other program elements that achieved equivalent savings. For Medicare as a whole, the Affordable Care Act has reduced by nearly half the anticipated increase in the program’s cost as a share of GDP. The currently projected increase is 2.1 percentage points over the next quarter century. That increase is not trivial, but in my view, it does not come close to meriting characterization that Medicare is in crisis or that

Medicare is unsustainable.[7]

Improved Backup Protection. The Affordable Care Act has not only directly improved Medicare financing, by raising revenues and reducing outlays. It has also created a back-up administrative safeguard, the Independent Payment Advisory Board. If growth of program outlays exceeds statutory targets, the IPAB is charged to design ways to hold growth of Medicare spending to those targets. The Congressional Budget Office believes that Medicare spending over the next decade will be within targets set in the Affordable Care Act and that the IPAB will not be required to act. But over the longer haul, this organization can help prevent Medicare spending from growing excessively. Congress is free to substitute alternative controls of its own design if it does not like the IPAB’s recommendations. I believe that some changes in the IPAB’s powers and organization could improve its effectiveness.

Health Insurance Exchanges. No plan that lacks aggressive regulation of insurance offerings and how they are sold merits designation as ‘premium support.’ No plan that lacks such regulation has any chance of enabling Medicare enrollees to make rational choices among plans, nor could it discourage competition based on risk selection. None of the plans now sailing under the premium support flag pays more than passing attention to this matter. None has drafted legislative language specifying how such regulation would be done.

As it happens, we are in process of designing health insurance exchanges. The Affordable Care Act invites states to create exchanges to regulate insurance offerings and sales to those who are not insured through work or through a public program. This effort shows that numerous practical and political problems must be solved in order to make these exchanges work. I have no doubt that these problems can be solved—and, with good will, they will be solved. But we do not yet know answers to some key questions. For example, we do not yet know whether state-based exchanges will work better than regional exchanges or a single national exchange. If the state exchange model is viable, we don’t yet know which forms of exchange will work best.[8]

Furthermore, the population to be served by the Affordable Care Act is both smaller and easier to handle than would be the Medicare population. The enrollees in the ACA exchanges will be neither elderly nor disabled. Millions of Medicare enrollees suffer from various degrees of mental impairment. For that reason, the ability of the ACA population to process information will be superior to that of the Medicare population. Because the level and variance of health spending among the ACA population is far lower than are those of Medicare enrollees, incentives for insurers to compete based on risk selection under the ACA will be smaller than they would be if the exchanges also covered Medicare enrollees. Health insurance exchanges that will operate well with the ACA population may or may not be able to handle the Medicare population. To move ahead now to commit to enroll the Medicare population in entities that do not yet exist and whose capabilities have not yet been tested and proved would be a rash legislative act carrying the threat of hardship and disruption. Only after the health insurance exchanges called for by the Affordable Care Act have been set up, only after the administrative problems they will doubtless confront have been solved, and only after we have some reason to believe that they will be able handle the much more challenging Medicare population—only then would it make sense for Congress to consider shifting Medicare enrollees to vouchers. Even then, it will be of critical importance to understand that the frailties of a large part of the Medicare population may mean that insurance models that make sense for comparatively healthy working age Americans may not make sense for the elderly and people with disabilities.

For similar reasons, the experience of the Federal Employees Health Benefit Plan provides little guidance one way or another to the desirability of giving Medicare enrollees a voucher and asking them to shop from a menu of competing private plans. The FEHBP population is better educated than the average American. Government agencies provide considerable information and enrollees have networks that enable them to guide each other to an extent that economically inactive retirees and people with disabilities do not possess. Most importantly, I am unaware of any evidence that the FEHBP has held down the rate of growth of health spending for its members below the growth of spending for the general population.

Change in Regulatory Climate. The role of government regulation has become vastly more controversial than it was in the 1990s. The kind of regulation of insurance offerings and marketing that I believe is a defining and vital element of premium support is simply unimaginable today. The political polarization around the matter of government regulation and the increasingly aggressive use of the filibuster in the Senate—which, I believe is a function of minority status, not party label—make it inconceivable that the sort of regulation necessary to make a market for health insurance genuinely competitive could win passage now or, if passed, be sustained. Without such regulation, in my view, the health insurance market under a voucher plan would likely be as deplorably inefficient as the non-group health insurance market is today. But the consequences would be far more serious—not just wasteful administration, and price distortions induced by adverse selection, but much worse, since the needs of the Medicare population are so large and insistent.

Failure of Risk Adjustment. A necessary element of successful competition under a voucher is effective risk adjustment. It is well known that health expenses are highly concentrated and are much higher, on the average, for Medicare enrollees than for the general population. Insurers who ‘get stuck’ with a lot of very sick people can lose a lot of money or even grow broke. Shareholders do not hire administrators to lose money or go broke. Accordingly, insurance administrators have a duty to the people who hired them to try to enroll healthier than average people. Of perhaps greater importance, they need to retain healthier-than-average enrollees. Because of these incentives, all competent health analysts have long recognized that, if premiums are uniform or vary less than expected cost, the key to a successful health insurance market is risk adjustment. Risk adjustment consists of financial transfers among insurers to offset the variations in expected health costs related to the characteristics of enrollees. Insurers that enroll people with comparatively low expected health care use would pay money to insurers that enroll people with high expected use.

In the 1990s, risk adjustment was inadequate. It was not then ‘good enough to discourage competition based on risk selection. But it was getting better. I assumed, perhaps too facilely, that it soon would get ‘good enough.’ Well, to date it hasn’t. Recent research has shown that the Medicare risk adjustment algorithm actually increased program costs by as much as $30 billion or 8 percent in 2006.[9] The problem is that risk selection increased along lines that were not included or could not be included in the risk adjustment formula. Plans have available many ways to attract customers expected to have low costs (“the X health plan is offering a free golf weekend”). They can also use the quality and availability of services to discourage high cost enrollees from remaining (“we are sorry, but our oncologist is booked solid for the next six weeks; no, he is the only one on staff”). They can also take steps to encourage low-cost enrollees to stay (“all current enrollees who remain in our plan will receive a free gym club membership”). The challenge of defeating such behaviors is never easy. But in an atmosphere hostile to aggressive regulation, it is impossible, particularly when the stakes are as high as they are with the Medicare population, whose costly patients are very costly indeed.

Medicare Competition Exists—the Results are Disappointing. To believe that competition does not exist in the Medicare program and that one must shift all enrollees to vouchers to create such competition is simply false. Medicare Advantage exists. It enrolls a quarter of all Medicare beneficiaries. It is well established. By 2010, the average Medicare enrollee could choose among an average of 24 plans, in addition to traditional Medicare — 10 health maintenance organizations, 4 local and 5 regional preferred-provider organizations, 4 private fee-for-service

plans, and 1 cost plan.[10]

Enrollments in Medicare Advantage plans have fluctuated with the generosity of payments to them. In some years MA plans have been paid more per enrollee than average costs in traditional Medicare—14 percent more in 2009. At such times MA enrollments have risen because MA plans could offer extras that Medicare beneficiaries value. When payments have been cut back, enrollments have fallen.

Fluctuating enrollments say nothing about whether competition from Medicare Advantage has lowered the cost of care. To answer that question, on needs to control for both the extra payments that MA plans have sometimes received and the extra services beyond the standard Medicare benefit package that they may provide. After one has adjusted for these factors, as well as enrollee characteristics, have Medicare Advantage plans been able to deliver the standard benefit package at lower cost than has traditional Medicare?

Until recently data to answer that question were unavailable. Thanks to a Freedom of Information Act suit, the relevant data are now available and the results are in. On average, Medicare advantage plans cost 3 percent more in urban areas and 6 percent more in rural areas than does traditional Medicare.[11] That is far from the end of the story, however. Relative costs vary enormously. MA plans are less costly than traditional Medicare in counties where roughly 30 percent of Medicare beneficiaries live. FFS plans are less costly than MA plans in counties where roughly 70 percent of Medicare beneficiaries live. One might suppose that where MA plans are comparatively cheap, a larger share of Medicare enrollees would choose them than in areas where FFS plans are comparatively cheap. To my surprise, no such pattern seems to exist. The lack of such a pattern dampens hopes that ‘cost conscious consumers’ will be the driving force for holding down health care spending.

Those who hope that providing Medicare beneficiaries with vouchers will help control costs often point to the fact that the costs of the Medicare drug benefit have come in far below preenactment estimates. Unfortunately, this claim does not withstand scrutiny. Events that are largely or totally independent of enactment of the Medicare drug program have caused total expenditures for drugs to fall short of estimates made in 2003 when Congress was debating the program. One of those events, the fall-off in the introduction of new ‘block-buster’ drugs, is hardly a cause for celebration. New drugs have brought benefits even larger than their costs.

The other trend—the growing use of generics—has been good news. The Medicare drug program may have accelerated the shift to generics and, thus, deserve some credit for the trend. But the simple fact is that Medicare part D costs have been lower than was estimated by a bit less than the cost of non-Medicare drugs have been below estimates made at the same time.[12]

In any event, drug costs are not the only criterion for evaluating Medicare part D. Of equal importance is whether enrollees in Medicare part D choose the plans that best meet their needs. Recent research suggests that they do not. By over-weighting premium costs relative to protection against risk, enrollees are choosing plans that do not provide them optimal protection.[13] They could improve their own welfare by choosing plans that cost a bit more up front, but provide more protection against heavy drug needs.

Erosion of Benefits. Many years ago, when Bob Reischauer and I floated the premium support idea, friends who supported traditional Medicare warned that vouchers, with or without our proposed safeguards, were a bad idea. Vouchers, they warned, are subject to erosion in a way that a defined-benefit plan is not. It is politically harder, they argued, to chop off a specific medical benefit—say, by limiting access to skilled nursing facilities or by capping the number of doctors visits permitted each year—than it is to shave a voucher. Which is more difficult is, of course, a matter of political judgment. But the many positions taken by the chairman of the House Budget Committee give me pause. Mr. Ryan has supported plans that would tie the value of vouchers, variously, to the growth of gross domestic product plus 1 percent (in proposals put forward jointly by Mr. Ryan and both Senator Ron Wyden and my colleague, Alice Rivlin), to the growth of gross domestic product plus ½ percentage point (this year’s Budget Committee proposal), or the consumer price index (last year’s budget proposal). The implications of these proposals over a period of many years are vastly different because of the inexorable force of compound interest. Even if one were prepared to disregard the many other elements that would—or should—go into a serious premium support plan, the “principle” involved in plans with such widely divergent adjustment formulas is so elastic that there is, in fact, no core principle at all.

VI

The Medicare program has succeeded in its fundamental goal of bringing standard care to vulnerable populations. It has innovated in designing new payments systems. It promises to be something of a hammer in forging reforms in the health care payment and delivery system. And it has delivered care at costs that are a bit lower than have competing private plans. Still, adjustments in the Medicare program can improve its operation. Given the purpose of this hearing, this is not the place to examine those changes in great detail. But I will list a few.

- 1. The Medicare Modernization Act shifted payment for drugs for dual eligibles from Medicaid to Medicare. The hope was that private pharmaceutical benefits managers would negotiate well enough to hold down costs. They haven’t. The result instead has been a sharp rise in the cost of providing drugs to dual eligibles. Various commissions and the president have proposed changes that would recapture all or most of those savings. The savings would exceed $100 billion over ten years.

- 2. The announcement of these hearings correctly pointed out that Medicare retains a structure common in 1960s private insurance. Combining parts A and B would have certain advantages. That said, simply imposing a single deductible and single cost sharing formula for both parts would boost costs for most enrollees, many of whom have very low incomes and can ill afford higher premiums. It would also violate the principles of value-based insurance design. While change is desirable, the form that change should take remains unclear. While change in the part A/part B structure is desirable, its exact form remains to be designed.

- 3. Medicare spends too little on administration. With a larger administrative budget, Medicare could do a better job of rooting out fraud and save the taxpayers far more than the small increase in the enforcement budget costs. Similarly, when Medicare approves a new procedure or treatment for specified situations, it now has too few administrative resources to make sure that guidelines are used. The result is overuse of new treatments in situations where approval is not granted and where evidence of effectiveness is lacking. Current restrictions on the CMS administrative budget are penny-wise economies that cheat both the taxpayer and Medicare enrollees.[14]

Conclusion

The U.S. health care system badly needs reform. Our payment system rewards quantity rather than quality. We waste huge sums on administration and at the same time neglect administrative outlays that could lower spending and increase quality. Medicare is part of that system and therefore is infected by many of those problems. But the problems of the U.S. health care system are not confined to or disproportionate in Medicare. Attention should focus on systemic reform. The Affordable Care Act has started us on that effort. That law is not perfect. In the course of its implementation we will learn a lot and encounter unanticipated effects that will cause us to change the law. But the successful implementation of health insurance exchanges is a necessary precondition for serious consideration of a voucher system. To bull ahead with a voucher plan of any stripe, before we have in place health insurance exchanges, an essential element if such a plan is to succeed, would be rash and irresponsible.

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Health Tracking Poll, February 2012

- The exact wording of the question is: “Which of these two descriptions comes closer to your view of what Medicare should look like in the future? Medicare should continue as it is today, with the government guaranteeing seniors health insurance and making sure that everyone gets the same defined set of benefits, OR, Medicare should be changed to a system in which the government would guarantee each senior a fixed amount of money to put toward health insurance. Seniors would purchase that coverage either from traditional Medicare or from a list of private health plans.

- Jennifer Epstein, “Poll: Taxing the rich favored over Medicare cuts,” Politico, 20 April 2011.

- http://rs9.loc.gov/medicare/talking.htm

- John D. Shatto and M. Kent Clemens, “Projected Medicare Expenditures under an Illustrative Scenario with Alternative Payment Updates to Medicare Providers ” 5 August 2010, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, p. 13

- Henry J. Aaron and Robert D. Reischauer, “The Medicare Reform Debate: What is the Next Step,” Health Affairs, Winter, 1995, pp. 8-30.

- Before enactment of the Affordable Care Act the Trustees Report projected growth of Medicare spending from 2010 through 2035 of 3.9 percentage points of GDP. The 2012 Trustees Report (p. 207) shows that Medicare spending will equal 3.72 percent of GDP in 2012, 5.73 percent of GDP in 2035 and 5.97 percent of GDP in 2040. The corresponding numbers from the 2009 Trustees Report were 3.6 percent in 2012, 7.23 percent in 2035 and 7.86 percent in 2040.

- In numerous essays written for the journal Health Affairs, law-professor Timothy Jost has explored a wide range of important, difficult, and solvable problems relating to the health insurance exchanges and other issues that have to be addressed.

- Jason Brown, How Does Risk Selection Respond to Risk Adjustment? Evidence From the Medicare Advantage Program, NBER Working Paper No. 16977, April 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w16977

- Marsha Gold, et al., “Medicare Advantage 2011 data spotlight,” Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2010. (Publication no. 8117) http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/8117.pdf

- Brian Biles, Giselle Casillas, Grace Arnold, and Stuart Gutterman, “Medicare Private Plan costs and Medicare Fee-for-service Costs: Do Private Plans Cost Less than Medicare Fee-forservices?: new Findings from New Data,” 26 September 2011; Brian Biles and Giselle Casillas, “Medicare Advantage Plan Costs and Medicare FFS Costs: Beneficiary Weighted, July 2009 Data,” 10 April 2012. Provided by [email protected].

- Edwin E. Park, “Lower-than-expected Medicare drug costs reflect decline in overall drug spending and lower enrollment, not private plans,” Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 6 May 2011 http://www.cbpp.org/files/5-6-11health.pdf.

- J. Abaluck and J, Gruber, “Choice inconsistencies among the elderly: evidence from plan choice in the Medicare Part D program,” American Economic Review, 2011;101, pp. 1180-210.

- Robert A. Berenson and John Holohan, “Preserving Medicare: a practical approach to controlling spending: timely analysis of immediate health policy issues,”. Washington, DC: Urban Institute, September 2011 http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/412405-Preserving-Medicare-A-Practical-Approach-to-Controlling-Spending.pdf.

Commentary

TestimonyThe Current State of Medicare

April 27, 2012