Editor’s Note: Elaine Kamarck testified before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform on June 18, 2013. Below are her prepared remarks:

It is an honor to be with you today and to discuss my experiences in government reform. In 1993 President Clinton and Vice President Gore hired me to run the National Performance Review. This project was the result of a 1992 campaign promise by then candidate Bill Clinton to “reinvent government,” a term taken from the best-selling book “Reinventing Government” by David Osborne and Ted Gaebler.

At the request of the President, this project did not end with the issuance of a report in September of 1993. Under the direction of the Vice President the project continued for the full two terms of the Clinton Administration. More reports were issued, but more importantly we tracked the implementation of every aspect of those reports. The duration of this effort (later renamed the National Partnership for Reinventing Government under my successor Morley Winograd) makes it the longest government reform effort in modern American history.

There are many ways to measure the results. Obviously there are the simple statistics. Under the leadership of President Clinton who said “The era of big government is over,” we went to work to make that a reality.

- We reduced the federal workforce by 426,200 between January 1993 and September 2000. Cuts occurred in 13 out of 14 departments making the federal government in 2000 the smallest government since Dwight D. Eisenhower was president.[1]

- We acted on more than 2/3 of NPR regulations, yielding $136 billion in savings to the taxpayer.

- We cut government the right way by eliminating what wasn’t needed – bloated headquarters, layers of managers, outdated field offices, obsolete red tape and rules. For example, we had cut 78,000 managers government-wide and some layers by late 1999.

- We conducted a regulatory review that resulted in cuts equivalent to 640,000 pages of internal agency rules.

- We closed nearly 2,000 obsolete field offices and eliminated 250 programs and agencies, like the Tea-Tasters Board, the Bureau of Mines, and wool and mohair subsidies. (Some of which have crept back into the government.)

- We passed a government-wide procurement reform bill which led to the expanded use of credit cards for small item purchases, saving about $250 million a year in processing costs.

But the reinventing government movement was not just about cuts, it was also about modernizing and improving the performance of government. In that regard the movement was responsible for starting three “revolutions” if you will, in government that continue to this day, built upon by succeeding Administrations. They are:

- The Performance Revolution

- The Customer Revolution

- The Innovation Revolution

The Performance Revolution

On August 3, 1993, President Bill Clinton signed the Government Performance and Result Act into law. GPRA provided the foundation for strengthening agency efforts to use strategic planning and performance measurement to improve results. On signing the bill, President Clinton said: “The law simply requires that we chart a course for every endeavor that we take the people’s money for, see how well we are progressing, tell the public how well we are doing, stop the things that don’t work, and never stop improving the things that we think are worth investing in.” The cornerstone of federal efforts to fulfill current and future demands was to develop a clear sense of results an agency wants to achieve, as opposed to focusing on the outputs (products and services) it produces and the processes it uses to produce them.

Adopting a performance-orientation required a cultural transformation for many agencies, as it entailed a new way of thinking and doing business. GPRA required federal agencies – for the first time ever – to prepare a strategic plan that defined an agency’s mission and long-term goals. Then agencies were required to develop an annual performance plan, containing specific targets, and then annual reports comparing annual performance to the target set in the annual plans. The Results Act included an extended schedule for implementation for its various components. Pilot projects on strategic planning and performance measurement were part of the initial learning phase in 1994, 1995, and 1996. The Act required agencies to submit their first strategic plans to Congress and the public on September 30, 1997.

Beginning in 1994, twenty-eight departments and agencies began a test run of GPRA through over 70 pilot projects for annual performance plans and reports. Full-scale implementation of GPRA occurred in FY 1999. By August of that year, according to a GAO report, Federal agencies were improving their ability to set goals and measures for their operations. But agencies were still struggling at explaining how they would reach their goals and verify their results. In a report released by three key Capitol Hill Republicans, GAO gave good marks to the Transportation Department, Labor Department, General Services Administration, and Social Security Administration for developing performance plans that explain what the agency plans to accomplish in fiscal year 2000. In March 2000, agencies released their first performance reports, which said whether they met their goals for fiscal 1999.

Since then, GPRA has expanded and thrived, unlike prior budget-related reforms such as Zero-Based Budgeting, which enjoyed a brief moment in the sun during the Carter Administration and was ultimately abandoned. During the Bush Administration OMB expanded upon the GPRA model by implementing a program-level assessment of performance, called the Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART), that ultimately assessed the performance of over 1,000 federal programs. Amendments to GPRA were passed in 2010 and signed into law by President Obama, putting into statute many of the successful administrative practices developed since 1993 that supplemented the statutory requirements. This seems to be an indication of the staying power of this particular reform.

But the performance revolution did not end with passage of GPRA. The NPR experimented with other strategies geared towards creating a performance culture in the federal government. In 1996 Vice President Gore built on his work implementing GPRA by pledging to create performance-based organizations (PBOs) that would “toss out the restrictive rules that keep them from doing business like a business.” A PBO was a government program, office or other discrete management unit with strong incentives to manage for results. The organization committed to specific measureable goals with targets for improved performance. In exchange, the PBO was allowed more flexibility to manage its personnel, procurement, and other services. Three PBOs were ultimately created: FAA’s Air Traffic Operations, the Patent and Trademark Office, and the Student Financial Assistance program. The performance of each of these programs improved over time, but in each case the parent departments limited the administrative flexibilities they had originally been granted.

To build leaders’ commitment and help ensure that managing for results became the standard way of doing business, some agencies used performance agreements to define accountability for specific goals, monitor progress, and evaluate results. Performance agreements ensured that day-to-day activities were targeted, and that the proper mix of program strategies and budget and human capital resources were in place to meet organizational goals. NPR worked with OMB and White House staffs to develop performance agreements between major agency heads and cabinet secretaries, and the President. As of the end of 1995, the heads of 8 of the 24 largest agencies had piloted the signing of performance agreements with the President- something never before done. OMB and NPR coordinated the development of additional agreements in 1996. While the use of presidential-secretarial level performance agreements faded, the legacy of creating a personal, rather than an institutional, commitment to performance was enshrined into the 2010 GPRA amendments with agency and cross-agency goal leaders being named and having a personal commitment to achieve the stipulated goal.

In January 1998, the Vice President asked the leaders of 32 “high impact agencies” to develop a handful of measurable goals that could be achieved over the next three years. High impact agencies were agencies that have the most interaction with the public and businesses, constituting ninety percent of the federal government’s contact with the public. About 1.1 million of the federal government’s 1.8 million civilian employees worked in these agencies. NPR helped these agencies set and meet “stretch” customer service goals built on the Government Performance and Results Act plans. They included IRS, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Social Security Administration. The objectives were included in OMB reviews of the agency budgets in order to help determine which programs were working and which had no impact on results. In addition, in 2000, those Senior Executive Service employees who worked in high impact agencies and who had responsibility for achieving one or more of the goals, were provided the opportunity to win annual bonuses based on their achievement of these goals, and improvements in customer satisfaction and employee involvement.

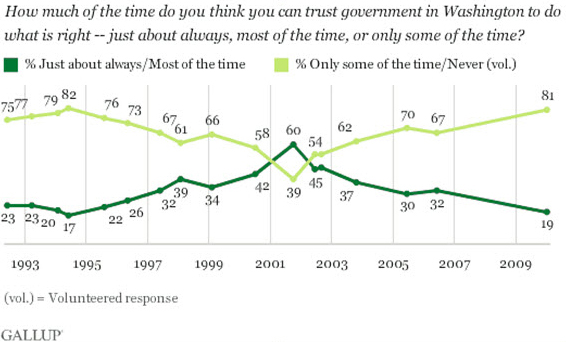

Source: Gallup, “Trust in Government: Historical Trends.”

It is believed that this improvement contributed to an increase in citizen trust in the operation of the federal government in the late 1990s, with citizen trust doubling in that period. (See Gallup poll above.)

The Customer Revolution

The Federal Government’s first ever customer service recommendations focused only on three agencies: IRS, Social Security, and the Postal Service. But the report also recommended a government-wide initiative.

After the first report was released on September 7, 1993, President Clinton began signing a series of government-wide executive orders to implement various recommendations in the report. The second executive order he signed was on Setting Customer Service Standards (the first was to cut red tape). The new executive order required all federal agencies to identify their customers and survey them to: “determine the kind and quality of services they want and their level of satisfaction with existing services,” within six months. And six months after that, agencies were to develop customer service plans and standards, and plan for future surveys.

Agencies initially hesitated, especially those with law enforcement or regulatory functions, but creating a customer service ethos in the federal government became an enduring theme of the Reinvention efforts of the Clinton-Gore Administration and served as a touchstone for the duration of the Administration.

The reason the president and vice president felt so strongly about this was their concern that Americans’ trust in the federal government had fallen dramatically and they believed that restoring trust was important to a vital democracy. Studies showed that citizens’ trust was closely linked to their perceptions about their personal interactions with government, hence the emphasis on customer service. In fact, when Clinton took office in 1993, citizen trust was at a record low of 21 percent. By the end of the Clinton administration in 2001, that level had doubled to 44 percent.

Agencies developed standards during the course of 1994 with the support of the President’s Management Council, which was comprised primarily of the deputy secretaries from the departments. The first standards report was issued in September 1994 and contained 1,500 standards across 100 agencies. This report was updated annually through 1997, when that report contained over 4,000 standards for 570 different federal organizations.

The message of “putting customers first” was conveyed to the rank-and-file staff across the government using a wide range of methods. It was one of the key criteria for Vice President Gore’s Hammer Award, given to teams of federal employees for reinventing their operations. It was also a key element of many Reinvention Labs, where teams of employees could pilot new innovations. The Vice President frequently held events around customer service initiatives in agencies and agency heads, such as Social Security’s Commissioner Shirley Chater, would be “mystery shoppers,” testing out their agencies’ phone call centers.

The Reinvention staff led a series of other activities and initiatives to support agency customer service initiatives, including:

- Sponsorship of cross agency best practices guides on topics such as world-class courtesy, 1-800 phone centers, and customer complaint resolution.

- Integration of customer service standards into agency performance measurement initiatives.

- Designation of “hassle-free” communities and “one-stop” websites for students, business, recreation, and a governmentwide site, now called USA.gov.

- The designation in 1997 of 32 “High Impact Agencies” which have the most direct interaction with the public – such as the IRS and Park Service – and their development of customer service initiatives that would make a noticeable difference to the public.

- The 1998 “Conversations with America” presidential directive, where agencies were directed to engage directly with their customers in conversations around the country on ways to improve customer service.

After 1997, the reinvention efforts shifted emphasis from developing and measuring progress against agency-determined standards to a greater use of customer feedback surveys such as the American Customer Satisfaction Index. The ACSI is a survey used by most of the nation’s leading corporations. And for the first time ever it was given to customers from over 100 federal services, such as the Postal Service and IRS. The results showed that some agencies which gave out benefits, not surprisingly, got higher customer satisfaction marks than many private sector companies. But other agencies whose purpose was to regulate their customers fared less well. Still, the insights from the surveys allowed all agencies to change the way they went about doing their job to make it more acceptable to those they served.

Perhaps the best example of this change in strategy was the huge push to get citizens to file their taxes electronically, after the IRS learned from their ACSI results that those who did so had a much higher level of satisfaction than those who filed their returns on paper. Today it is a commonplace experience. Fifteen years ago it was revolutionary. Customer surveys, it was believed, would be less likely to result in lower standards, which agencies might be tempted to set in order to be judged as successful. This was based on observations of the British Citizens Charter movement, which saw agency standards steadily decline over the previous decade.

The George W. Bush Administration did not actively pursue a customer service initiative, but it did not repeal the Clinton directives and it allowed the continuation of the ACSI surveys in agencies. And in 2007, Congressman Henry Cuellar proposed legislation to mandate the creation of customer service standards and link them to employee performance appraisals. It passed the House in two Congresses, but failed in the Senate. At the request of the Senate, the Government Accountability Office examined federal customer service initiatives in 2010 and concluded that including customer service standards as a part of federal employee performance assessments “is an important factor in assessing employee performance,” but that this needs to be done in ways that are appropriate. Congressman Cuellar has reintroduced a bill in the current Congress.

Separately, President Obama sought to reinvigorate customer service efforts via an April 2011 executive order, which directed agencies to develop new customer service plans within six months and to undertake at least one signature initiative using technology to “improve the customer experience.” Agencies have posted their customer service plans and they are being implemented.

The Innovation Revolution

The 1993 Report of the National Performance Review ushered in an era of reinvention, modernization and innovation. The approach to innovation was twofold. It assumed that the employees of the federal government who did the day-to-day work of the government were the ones best able to bring forth ideas for improving performance and cutting costs and that they needed permission and encouragement to change the culture from complacence to innovation. It also sought to bring the information technology revolution that was affecting so many different parts of American society into the operations of government.

In order to create a culture of innovation, the NPR initiated several new programs. Agencies and offices were encouraged to apply to become “reinvention laboratories.” Once designated a “reinvention lab” the agency was encouraged, with the help of the NPR staff, to try new ways of doing business. With the backing of the White House, the reinvention labs were encouraged to think outside the box and not be afraid to fail.

A second project geared towards stimulating innovation was an award program known as the “hammer awards.” The “hammer” in the award referred to the mythical $700 hammer that the Pentagon had bought and that captured, in the public’s mind, everything that was wrong with government. And so the NPR team created the hammer award for those federal employees who did exactly what the public thought they couldn’t do –tear down something that wasn’t working and build something better. In and of themselves these awards were not very fancy. The hammer award consisted of a cheap hammer, tied with a red ribbon and mounted on a blue velvet back background that contained a card from Vice President Al Gore that read “Thanks for creating a government that works better and costs less.” The awards were publicized throughout the federal system and they achieved their goal of encouraging others to innovate as well. They can still be found hanging proudly in federal offices throughout the country and many re-inventors still wear the little lapel hammer pin they got for participating in an award winning project.

The third program designed to facilitate innovation was the formation of The National Partnership Council. This was a high level group geared towards moving the federal government and its unions away from overly legalistic and adversarial bargaining and towards a more cooperative relationship. Only by working with unions and with employees could the culture change in the direction of more innovation.

The second major portion of the innovation revolution was to bring the new information technology that was transforming American society into the public sector. When the National Performance Review was formed few Americans knew about the Internet. President Clinton liked to say that when he was inaugurated there were only 50 sites on the World Wide Web, which was a term just becoming popular. No one “Googled” anything, the term wasn’t even in use. But the Vice President, who, as a Senator had taken the Internet out of the military sphere, and written the legislation that allowed it to become a private sector tool, had a vision for how the Internet could change government.

Under the leadership of NPR, the federal government entered the Internet Age. In 1997 the NPR published Access America: Reengineering Through Information Technology. In an age when less than 25% percent of the public was online, this report summarized what was to come. The Internet would be used to bring information to the public “on its terms.” Information technology made it possible to begin implementation of a nationwide electronic benefits transfer program, to integrate information in the criminal justice community and to provide simplified employer tax filing and reporting. It also began the integration of government information through the creation of firstgov.gov – the federal government’s first, comprehensive web portal, launched in 2000.

Today it is called USA.gov, but its purpose is the same – to offer citizens one stop access to government information. As the Internet evolved, the goal was able to move from access to information to actual transactions. Today the majority of Americans pay their federal taxes online and conduct many other transactions at the federal, state and local level online as well. Thanks to the dedicated efforts of many original NPR staffers who continued to work on this project through the Bush administration and then in the Obama White House, the federal government is no longer an institution looking from the outside in at IT innovation, but instead plays a key role in breaking down barriers between government and its citizens everywhere.

Lessons for Future Government Reform Efforts

It has been twenty years since there has been a major reform undertaking by the U.S. federal government. This is no one’s fault. The Bush Administration had to cope with an unprecedented attack on American soil and a subsequent war; the Obama Administration had to cope with an economic emergency unparalleled since the Great Depression. Neither Administration can be blamed for not making government reform a central focus.

Now, however, as we (hopefully) return to a more normal time, these two emergencies have left us with a huge national debt while, at the same time we have an exploding elderly population. The time has come to take a new and comprehensive look at the operations of the Federal Government with an eye towards reducing that debt and improving efficiency. So here are a few reflections from my experience in the White House in the 1990s and my experience at Harvard University where I was on the faculty studying and teaching these issues.

First, there are two ways to cut the government. One takes an across the board approach, as the sequester does. It assumes that all government is created equal. In that approach there is no attempt to differentiate efficient from wasteful; critical from obsolete. This is, obviously, the politically easy approach but not the substantively most valuable approach. Second, is the way we did this in the 1990s. We recruited a staff of experienced civil servants to help us understand where the government was going wrong and where it needed help. As a result we focused on government wide policies like procurement and we also focused on problems within individual departments and agencies.

Second, as the Government Transformation Initiative points out, the same “problems” are identified year after year and never solved. The reason is that each one has to be considered on its own. There are no easy solutions. For instance, this is why “reorganization authority” is not the answer. Often programs that appear to be doing the same thing are actually not. Furthermore everyone has different authorizing statutes that would need harmonization. The bottom line is that some “stupid government” stories are actually not stupid and some are. It takes a careful in-depth approach to separate the two.

Third, show me an inefficient, obsolete or wasteful government practice or program and I can promise you that someone in the private sector is making money off of it. Not surprisingly, people who make money from government ineptness are loath to see it end. The case is never presented that way but a strong counter-force is needed to overcome special interest pleading.

Fourth, calculating efficiency in the government often involves a complex process of finding similar private sector “bench-marks” against which we can measure government efficiency. Again, the story is complex and often obscured by the large numbers of dollars the federal government deals in. For instance, the amount of fraudulent Social Security retirement checks paid to seniors in any given year is likely to be a number that seems enormous to the American people. But at payments of $821 billion per year in old age and retirement insurance, small amounts of fraud result in large amounts of dollars. Thus the calculation of waste, fraud and abuse needs to be made in the context of similar processes in the private sector.

Fifth, it is career bureaucrats who know, better than anyone else, what works and what doesn’t. A successful reform effort cannot take place without their wisdom and without their participation. As with any workplace the federal workplace is composed of a wide variety of character and talent. For every civil servant who ties up citizens in red tape and doesn’t seem to work very hard, there are civil servants who work overtime making sure that our soldiers’ families get what they need or who makes less money than they could in the private sector to make sure we are funding essential medical research. We need to reward the civil servants who produce for their fellow citizens. In addition, the federal government consists of a whole lot of very good people caught in a whole bunch of very crazy systems. Of course at the time each rule was created it made sense, solved a problem and worked in the public interest. But over time the accretion of rules and regulations ends up costing us money and frustrating the public.

Conclusion

It has been twenty years since there has been an across the board analysis of government reform. Much of what we did back then in the Clinton Administration is standard operating procedure now in the government. It is time, however, for a new burst of creativity. We face two challenges: budget deficits are at all time highs and the trust deficit of the American people is at all time lows. A serious bi-partisan reform effort could do wonders for both deficits.

Thank you for this opportunity to share my views on this important subject.

[1] This number does not count temporary workers hired to conduct the 2000 Census.

Commentary

TestimonyLessons for the Future of Government Reform

June 18, 2013