Echoing Mao Zedong before him, Xi Jinping regularly stresses the Party’s domination of all aspects of life. “East, west, south, north and center, Party, government, military, society and education—the Party rules all,” as he has said. The latest target of this drive to domination is “fandom culture,” or fanquan wenhua, which refers to online youth communities that coalesce around shared obsessions with celebrity idols. According to the Cyberspace Administration of China, “toxic idol worship” threatens to poison the minds of future generations. Last month, a newspaper published by the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Propaganda Department warned that internet addiction among teenagers “results in health risks that cannot be ignored.”

This effort to control fandom culture comes against the backdrop of a crackdown on youth entertainment in China, including harsh restrictions on online gaming. But all this talk of rescuing Chinese youth from their own appetites is in fact a smokescreen for a far more serious purpose. Closer scrutiny of China’s recent internet crackdown suggests these moves are part of a broader effort to reassert the Party’s control over the internet as a key battleground for political and ideological security. The struggle, which touches on the future of the regime, is for the hearts and minds of China’s Generation Z. For policymakers considering how to respond to China’s crackdown on online freedoms, it is vital to understand the full scope of its efforts to consolidate power, which go far beyond just the tech industry to include online culture.

In the eyes of the Party, the country’s hitherto vibrant internet and entertainment sector is a thing to be tamed, and the official backlash facing fandom culture in recent weeks is one of the clearest examples of how even apparently benign aspects of the internet can run afoul of a leadership obsessed with control. Just as the Xi regime has sought to bring the country’s technology companies to heel, it also seeks to control online culture more deeply, and this does not bode well for the long-term development and vibrancy of China’s internet sector.

From stargazing to collective action

For many young people in China, particularly those born after the 1990s, fandom culture—which can be traced back to the idol worship of the 1980s and 1990s—has offered a rare avenue for identity formation and community building in a society where associations of all kinds are subject to strict government control. As networked and often highly organized communities of fans rallying around their beloved idols, “fandoms” have enabled close parasocial interactions in which fans feel a kind of intimacy with the object of their shared interest, as well as a sense of active participation that can be empowering and identity forming.

Examples of fandom culture include the hit show “Idol Producer,” which launched in January 2018 on the online video platform iQiyi and empowered fans to select and promote their favored contestants from among 100 aspiring performers. The ultimate goal of the program was to select nine performers to form a brand-new male idol group. As fans organized to promote their favored idols through social media platforms, their interactions were fueled by Gen Z-focused services like live-streaming and live commerce.

Fandoms have become big business in China. A report published by iResearch Consulting Group put the market value of the fan economy in China at close to $620 billion in 2019 and estimated that the fan economy would grow a further 50 percent by 2023.

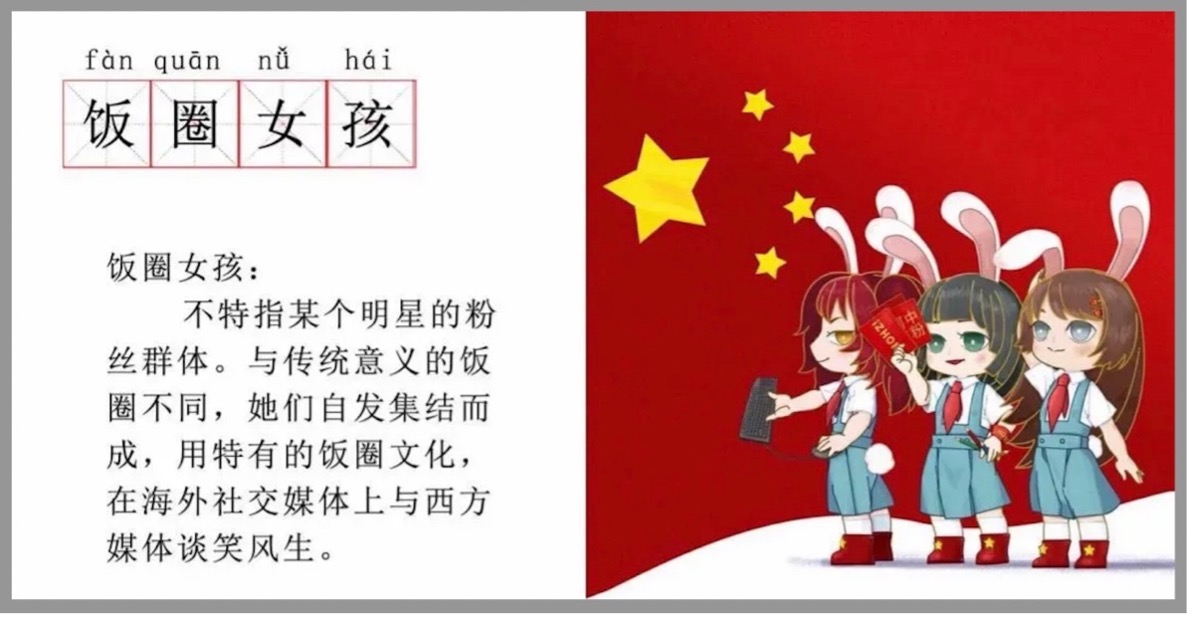

It would be easy to dismiss fandoms as shallow and celebrity-obsessed, but the highly organized online communities forming around China’s fandoms have already demonstrated their potential for both social activism and political organization. Perhaps the most prominent example of online fandom communities’ potential for political expression came in 2016, when the so-called “Diba expedition” saw thousands of highly organized cyber-nationalists, mostly “fan girls,” mob the Facebook account of Taiwan’s newly elected leader, Tsai Ing-wen.

Fandoms and their capacity for collective action were also one of the largely untold stories of China’s fight against the COVID-19 epidemic in its early stage. In January 2020, as it became clear that an epidemic had emerged in Wuhan and surrounding areas, the government response was far too slow in many key areas, including the provision of protective equipment. By contrast, the networks already formed within fandom culture—the same that allowed mobilization in support of chosen idols—enabled the rapid marshalling of resources. On Jan. 21, 2020, one day after China confirmed human transmission of COVID-19, the fan network of Zhu Yilong, a young actor originally from the city of Wuhan, mobilized funds to purchase more than 200,000 protective masks. These and other supplies were delivered to Wuhan within 24 hours, offering much-needed support for medical personnel and others on the front lines. The aid offered by the Zhu Yilong network is just one of many examples of how online groups provided a crucial means of support amid a rapidly unfolding crisis.

Perhaps more worrying for the CCP has been their potential for mobilization on a global scale. Within 10 days of China’s formal acknowledgement of the coronavirus outbreak in January 2020, a group of 27 fandoms from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan known as the “666 Alliance,” had sourced nearly half a million-yuan worth of medical supplies for use in Wuhan. As one Chinese scholar wrote of fandoms in 2020: “They are a huge population, are well-organized, and have a clear division of labor, giving them an explosive power many would find astonishing.”

Guiding Gen Z

The Chinese leadership understands the immense impact youth movements have had in the country’s political past—from the May Fourth Movement at the start of the 20th century, to the chaos wrought by Mao’s Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s, to the large-scale pro-democracy demonstrations of 1989. It may seem a stretch to compare such historical upheavals to the myriad iterations of online youth culture in China today. But it is important to recall that the most enduring lesson Party leaders took away in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Massacre was the imperative of mastering the social zeitgeist, ensuring especially that the thoughts and ideas driving China’s youth can be directed through effective controls on culture and the media. As China’s reform-minded premier, Zhao Ziyang, was shoved aside in the wake of the massacre, and as Jiang Zemin assumed leadership of the Party, the project of ensuring the control of news and ideology to preserve regime stability was given a new catchphrase: “guidance of public opinion.” The phrase came directly from language in the Party’s assessment, published in the journal China Comment, of Premier Zhao’s failings of that spring.

Meeting with propaganda leaders in May 1989, as pro-democracy demonstrations continued to grab international attention, Zhao had urged the officials to open things up a bit. “Make the news a bit more open. There’s no big danger in that,” he said. “By facing the wishes of the people, by facing the tide of global progress, we can only make things better.” The consensus from the start of the Jiang era was that Zhao’s tolerant approach had “guided matters in the direction of chaos,” hence the phrase that came to dominate the project of media and internet control for decades to come.

The CAC’s Aug. 27 notice on fandom communities—“Notice on the Further Strengthening of the Management of ‘Fandom Chaos’”—describes the political objectives driving this clean-up of “fandom chaos.” The notice says that “all regions must further improve their political stance,” or zhengzhi zhanwei, which is a term that came to prominence in 2018 to signal allegiance to Xi Jinping and the CCP. The term is a distillation of what is known as the “Four Consciousnesses,” which is fundamentally about Xi Jinping’s “core” status. Crucially, the notice urges government authorities in all regions of the country to govern “fandom chaos” in order to “preserve online political security and ideological security and create a clear online space.” This spells out far more clearly—by the standards of China’s often obscure political rhetoric, anyway—the urgency of controlling fandom culture in order to maintain the stability of the regime. There is also explicit language about the need for platforms that host fandom activity to take on a “guiding responsibility,” a subtle yet unmistakable reference to the aforementioned media control phrase and the events of 1989.

China’s leadership has been pushing insistently for better “guidance” of fandom culture since at least the second half of 2020. Fandoms came under much greater official scrutiny from February to July of 2020 following an online controversy centering on Xiao Zhan, an actor and internet idol. When AO3, a fan fiction site outside China played host to an overtly homoerotic work of fan fiction about Xiao and a former co-star, some of Xiao’s millions of fans were enraged. They retaliated by reporting the fan site to government authorities, who answered with a wholesale blocking of the site from inside China. This prompted bitter reprisals against Xiao Zhan fans, including name-calling and doxing, from other fandoms dedicated to AO3. Xiao quickly became a toxic figure for major brands like Cartier and Estée Lauder, who backed out of endorsement deals.

The online storm around Xiao Zhan became known as the “227 Incident” (referring to the date it began, Feb. 27) and brought a wave of official criticism in the Party-state media. One official newspaper wrote via its news app in early May 2020 that fandom culture is a “highly-organized” threat to ideological security. The role of fandoms in “self-identity construction” had caused them to “constantly intrude upon or subsume other ideologies to form a fierce and aggressive and highly-organized machine.” Fandoms’ “potential social influence in broader arenas” cannot “be underestimated,” the paper warned. Following an initial apology in March, Xiao Zhan again issued a mea culpa in July 2020, using the Party’s own language of ideological control: “I do have a duty to guide correctly and to actively advocate [for the correct values].”

By July 2020, the stage was set for this year’s curbs on fandom culture as part of a much larger crackdown on China’s internet. From that point on, “fandom chaos” was a regular topic in the official media. A headline that month in Guangdong’s official Nanfang Daily read: “Relevant Departments Focus on ‘Fandom’ Chaos: Media and Celebrities Must Properly Carry Out Guidance of Public Opinion.”

Idolizing the general secretary

Attacks on fandom culture and online entertainment in China’s state media this year have continued to dwell on the impact on the health and well-being of young people and on the damage supposedly done to the country’s “online ecology.” But accepting this official rationalization for the crackdown on fandoms requires that we turn a blind eye to the most defining trend in Chinese domestic politics today—namely, the Party’s push to build a culture of loyalty, and even infatuation, around the person of Xi Jinping. Celebrity worship may be on the way out in China. But strongman worship is the order of the day. By cracking down on fandoms, the Party seeks to ensure that the vigor of celebrity worship is re-directed toward Xi Jinping himself, as the embodiment of Chinese ethics and values.

Despite all the chatter in the official state media about the “chaos” of fandoms, the push to make China’s internet giants to give back, the need to safeguard data privacy and official morality, and so on, the most fundamental driver behind wave after wave of new internet restrictions this year has been far more basic: the need for the Chinese Communist Party and its charismatic leader to shore up the foundation for political and ideological stability. On Aug. 24, just three days before the Cybersecurity Advisory Committee issued its new regulations on fandom culture, China’s Ministry of Education announced that the study of Xi Jinping’s personal governing concept will be incorporated into the official education curriculum, helping China’s youth “build faith in Marxism.” Primary school children in China—now restricted to their two hours of online gaming per week—will now also be obligated to study not just the governing concepts of Xi Jinping, but to study and internalize the stories of Xi’s life and deeds. The country’s leaders may decry a commercial internet culture in which everyone is “striving for eyeballs.” But the fundamental point here is that the Party too is striving for eyeballs. And its future, it knows, will depend on China’s obsessed youth.

David Bandurski is the co-director of the China Media Project, a research program in partnership with the Journalism & Media Studies Center at the University of Hong Kong.

Facebook provides financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

Commentary

Why China is cracking down on its online fandom obsessed youth

November 2, 2021