When unprecedented protests erupted last week in Cuba, some observers were quick to argue that improving access to the internet had made possible a protest movement in a country where freedom of speech and assembly are significantly restricted. As with the Arab Spring, these techno-optimists saw the power of the internet at work in a Cuban protest movement that coalesced around long-promised, long-delayed economic reforms and a fumbling response to spiking COVID-19 cases. President Biden even suggested that providing private internet to the Cuban people might be a strategy the U.S. government could pursue. But a closer look at the data reveals a more complicated picture that should make policymakers cautious in relying too much on internet access as a tool to counter sclerotic authoritarians.

Based on an analysis of nearly four million Facebook posts from public pages and groups from June 1, 2019 to July 20, 2021, Cubans have become more engaged on Facebook, both in terms of the volume of content and average engagement with posts. Since July 2019, when the Cuban government began lifting restrictions on internet access, total content has grown steadily over time. In the lead up to the most recent wave of protests, average engagement with content on Facebook grew rapidly, spiking on July 13, 2021, two days after the eruption in protests and a day after the Cuban government restricted internet access. Since then, the volume of and engagement with Facebook content has dramatically declined. As of July 21, it has yet to return to pre-protest levels, likely due to government shutdowns, though the focus of conversations that are still ongoing has not fundamentally changed. Though a Facebook live broadcast is largely credited with sparking the most recent wave of protest across the island, policymakers should be careful not to overemphasize the role internet access is playing in fomenting this recent protest movement.

Liberation by web

The vision of the internet as a “liberation technology” was first articulated a decade ago during the height of the Arab Spring, in which activists used social media to organize protests across the Middle East. Academics, pundits, and policymakers around the world, heralded the internet’s potential to “expand political, social, and economic freedom” and create “a new nervous system for our planet.” In his historic 2016 trip to Cuba, President Obama urged the government to support the expansion of the internet across the island, calling it one of “the greatest engines of growth in human history,” and made internet access a priority issue for his administration’s Cuba policy.

Since that visit, the number of people in Cuba with regular access to the internet has nearly doubled. The country has leap-frogged its neighbors, with internet penetration rates in Cuba improving from one of the worst in Latin America to fairly typical for the region, according to World Bank figures. Today, internet access rates in Cuba are similar to those of Colombia. Not long ago, Cubans relied on “El Paquete Semanal”—a terabyte-sized thumb drive containing static screen shots, music and television shows, among other content—for a weekly snapshot of the digital world. Today, they can access the internet from the comfort of their own homes, a reality made possible when the government cautiously relaxed internet restrictions across the island in 2019.

A glimpse inside Cuba’s Facebook boom

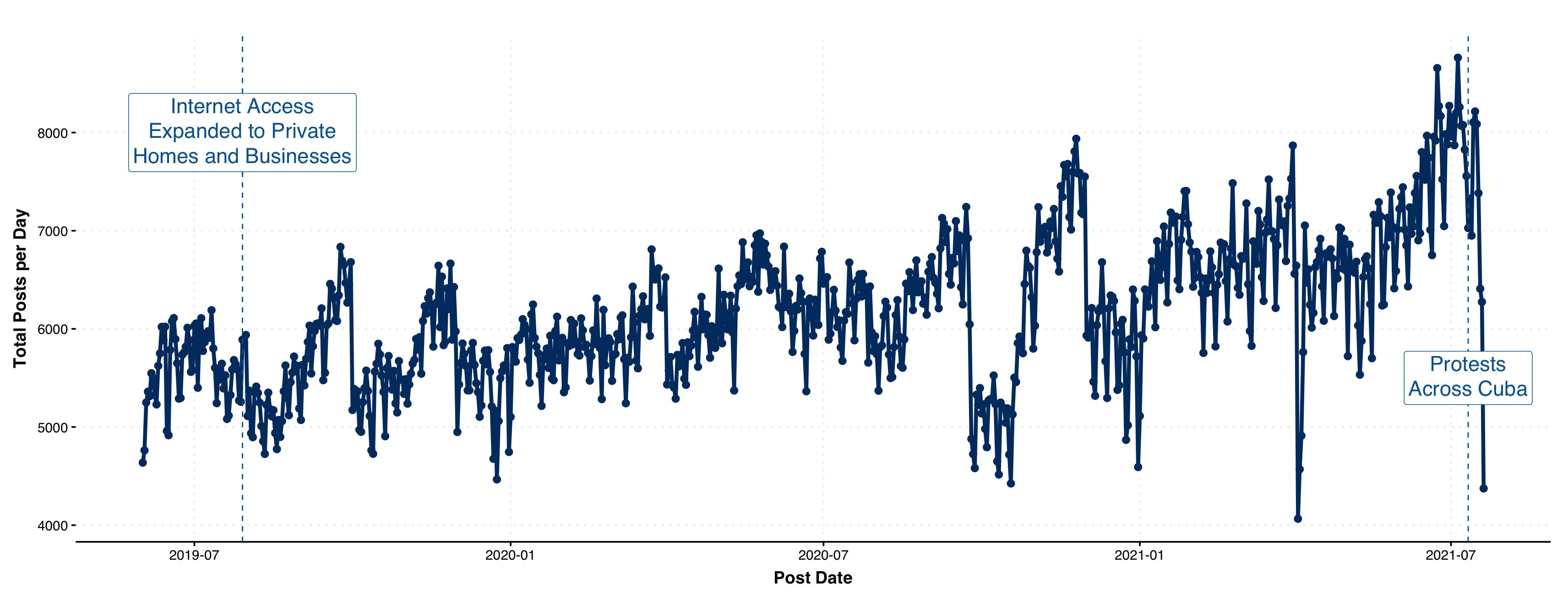

Although most traditional social media platforms remain underutilized among the Cuban population, Facebook is wildly popular, accounting for more than 76 percent of all Cuban traffic to social media sites in 2020. Figure one plots the growth in Facebook content in Cuba from June 1, 2019 through July 20, 2021.[1] The figure reveals steady growth over time, with some localized peaks and valleys. By the time the protest began in Cuba on July 11, the volume of total content had already begun to decline, though the dip would become far more evident in subsequent days. To date, the amount of original content has not returned to normal, likely due to continued access restrictions, and remains at a lower level than prior to the expansion of the internet across the island.

Figure 1

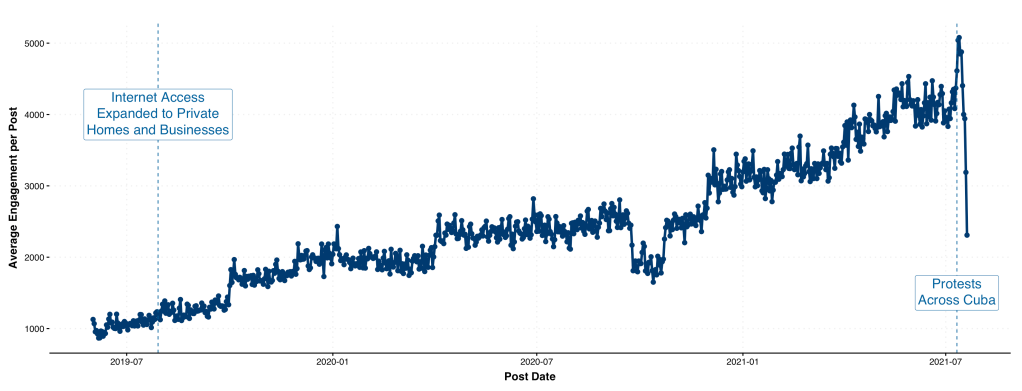

Figure two shows the average engagement with posts during the two-year period. Over time, average engagement with posts (in the form of likes, comments, etc.) has increased, as more and more Cubans have come online. This suggests that with content steadily rising more people on average are engaging with that content. Average engagement with posts has grown by more than 400% over this time period, as compared to around 33% for the total volume of posts. Perhaps what is the most striking to note is that just prior to the protests, average engagement with posts dramatically spiked online, suggesting that Facebook content—while not as voluminous—did reach more people immediately before the protests. Engagement levels peaked a day after the Cuban government began to block internet access across the island and plummeted in subsequent days to levels not seen since late 2020.

Figure 2

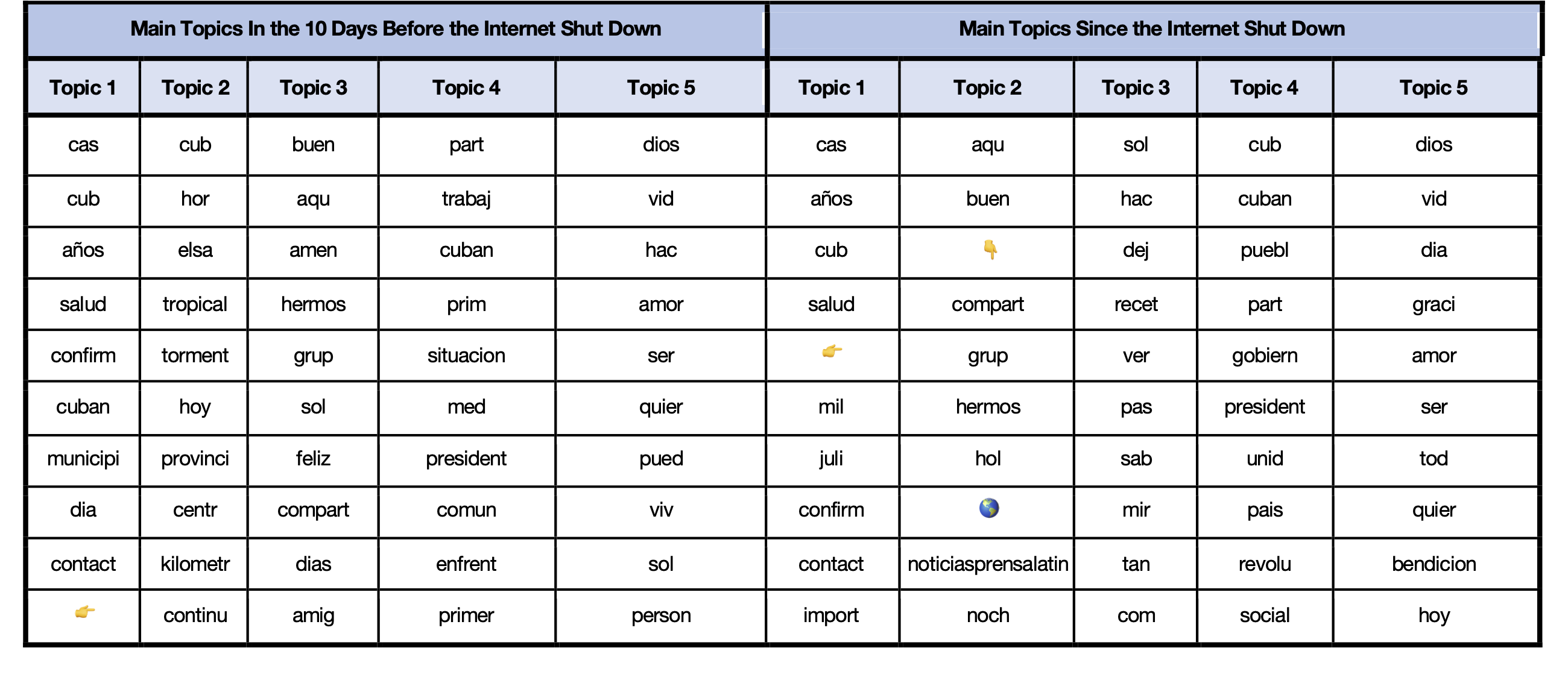

Interestingly, although the number of and engagement with these posts has declined rapidly over the past week, Table one shows that the types of content that users are sharing has not fundamentally changed. This suggests that while the Cuban government might have been successful in shutting down access to content for many, it has not managed to shift the substance of these conversation online, which remain focused on similar themes like the pandemic (Topic 1), politics (Topic 4), and religion (Topic 5).

Table 1

The road forward

It remains to be seen how long internet access will be restricted across Cuba or if this decline is only temporary or more enduring. Cutting off internet access is not a particularly new strategy for the Cuban government to control the information environment and curb dissent. If past dips are any indication, we should expect the level of and engagement with Facebook content to eventually return to prior trends.

In this case, shutting down the internet has, at least for a time, succeeded in curbing the coordination mechanism offered by social media and—coupled with a violent crackdown against demonstrators—the momentum generated by last week’s protests. But these protests, while much larger in scope, are not new either, and the grievances that drew Cubans to the streets in record number have not fundamentally changed. Despite restrictions on access, the nature of online conversations is also not dramatically different. This suggests that online (and potentially, offline), Cuban citizens will continue to focus their attention on the same issues that motivated them to protest in the first place, especially if their situation does not materially shift soon.

While the extent to which Cuba’s protests were fueled by social media remains unclear, the Facebook data, with its peak right before the protests and dramatic decline after the internet shutdown, highlights the importance and urgency of the debate. Policymakers and the tech sector should examine this case further to better prepare for future events in Cuba and beyond, while simultaneously recognizing the limitations of technology alone in driving political change.

Valerie Wirtschafter is a senior data analyst in the Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technologies Initiative at the Brookings Institution and a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Facebook provides financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

[1]This data is collected from Facebook’s CrowdTangle API, with geographic filters for content from pages and group tied to or largely trafficked by accounts in Cuba.

Commentary

What role did the internet play in fomenting Cuban protests?

July 23, 2021