No history of China and the internet would be complete without reference to what in retrospect must be one of history’s poorest metaphors. In March 2000, President Bill Clinton famously noted that “the internet has changed America” and that it would likely do the same to China regardless of the “Great Firewall” it had built: “There’s no question China has been trying to crack down on the internet. Good luck! That’s sort of like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall.”

With the benefit of hindsight, Clinton failed to appreciate the real intent of Beijing’s approach to internet governance. The Chinese Communist Party’s objective in controlling public opinion is not to nail it to the wall but rather, like Jell-O, to mold it. Ever since the bloody crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in 1989, the CCP has conceived of information control as a process of “guiding public opinion,” of applying the vast apparatus of the propaganda department and the party-state press to mold the individual’s sense of truth, thereby maintaining the stability of the regime. And ever since the dawn of the internet, the Party has safeguarded the domestic project of “guidance” by restricting access to the global internet by means of the “Great Firewall,” a vast system of human and technical controls.

Today, twenty years after Clinton’s quip, the CCP’s grip on information is perhaps more assured than it has been at any time in the reform era. Thanks to new tools of control and surveillance, in addition to the reconsolidation of media and internet oversight, the Chinese internet has proved an exceptionally moldable medium. This experiment in technology-empowered social and political molding has been so successful that the Party now appears to be experimenting with technologies to allow Chinese internet users to access the web beyond the Great Firewall—while maintaining key features of the Party’s censorship regime.

On Oct. 9, a company backed by China’s largest cybersecurity company, Qihoo 360, released Tuber, an app for Android in China that enabled the browsing of content outside the Great Firewall, including banned sites like Google, YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Netflix. A blurb on the app’s dedicated webpage noted that “Tuber has passed the review of relevant competent authorities and obtained an online operating license.”

Tuber’s launch met with a frenzy of excitement, and the topic trended in chat groups on the popular WeChat platform, as well as on social networking services like Douban and Zhihu. It quickly became apparent to users that while foreign websites could be accessed through the app, sensitive results were still restricted. There were quips that the circumvention tool had been “castrated.”

Regardless of the restrictions imposed, the app’s release was viewed by some as a huge development for information management in China. Rita Bai Yunyi, a reporter for the state-run Global Times, hailed Tuber as a way to connect to sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Google without a VPN, while “still censoring fake news or propaganda like [the] Epoch Times,” referring to the overseas Chinese publication affiliated with the Falun Gong spiritual movement, which is banned in China. She called the app “good for China’s stability” and “a great step for China’s opening up!” Others were more cautious, noting that users were required to register with their mobile numbers, tied to personal ID numbers, to access news sites.

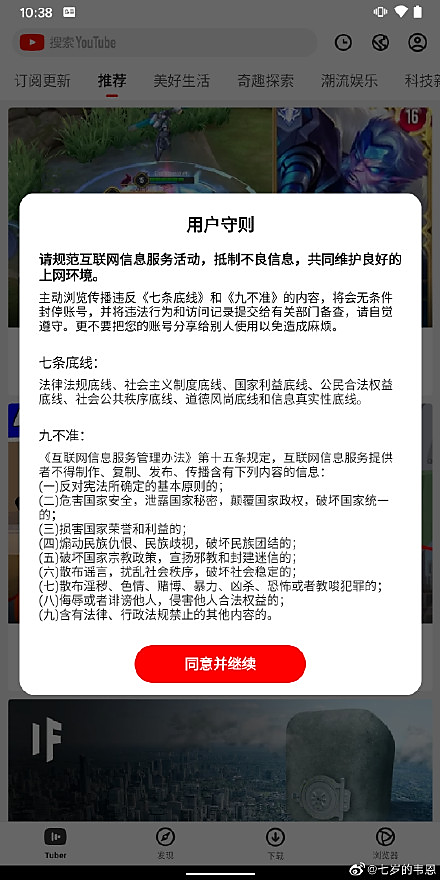

Though it opened a window to the non-Chinese web, Tuber still appeared to abide by Chinese information controls. The user rules for the app stated that any users browsing or disseminating content in violation of the so-called “Seven Bottom-Lines” or the “Nine Prohibitions” would be logged and reported. The former are guidelines released by the powerful Cyberspace Administration of China in 2013 that broadly define unacceptable content. The latter is shorthand for the 2015 Administrative Regulations on the Account Names of Internet Users, which bans a broad range of behavior on the internet, including harming national security, subverting state power and damaging the national reputation—all of which are subject to broad interpretation.

Tuber made clear that it would share user logs with the “relevant authorities,” and its privacy policy stated that the collection of personal information related to national security would not require user authorization. All of these conditions had to be accepted before the app could be used. After testing the app, one user inferred from his experience that it implemented at least two layers of filtering, the first censoring video results as they loaded, the second filtering keywords as users conducted searches: “Obviously there is a process of loading [videos] one by one, and keywords used in the search process are again filtered – use this with extreme caution.”

Despite its adherence to Party information controls, interest in the app was strong—reflecting broader demand, particularly among young Chinese, for tools to connect with the outside world. Within 24 hours of its launch, nearly five million people had downloaded Tuber.

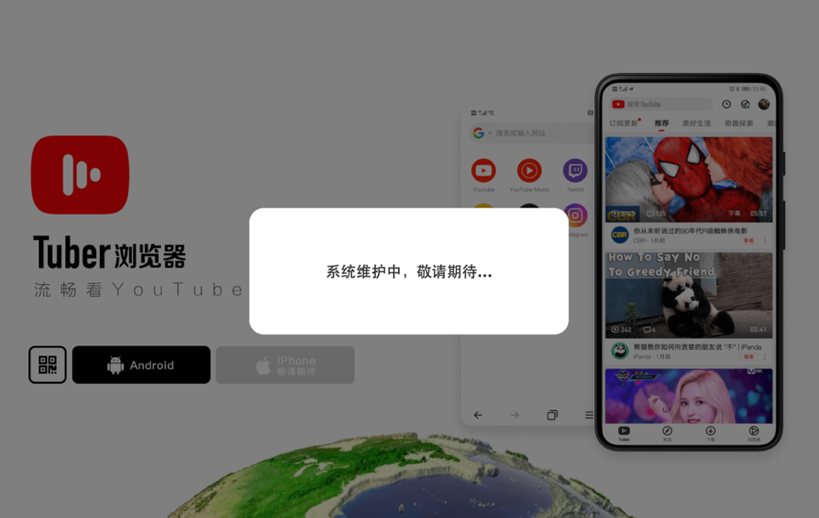

But this experiment in (relative) internet openness did not last long. A day after its launch and without explanation, Tuber vanished from app stores on Oct. 10. The message on Tuber’s official website, tuber.cn, read simply: “System maintenance, stay tuned.” The website has since gone entirely offline.

Asked about the app’s disappearance during an Oct. 12 press conference, Foreign Ministry Spokesman Zhao Lijian dismissed questions about Tuber as “not a diplomatic issue” and added that “the internet has always been managed in accordance with laws and regulations.”

Tuber leaves a host of questions in its wake. Why was the app, with backing from a major technology enterprise with close ties to the government, released in the first place?

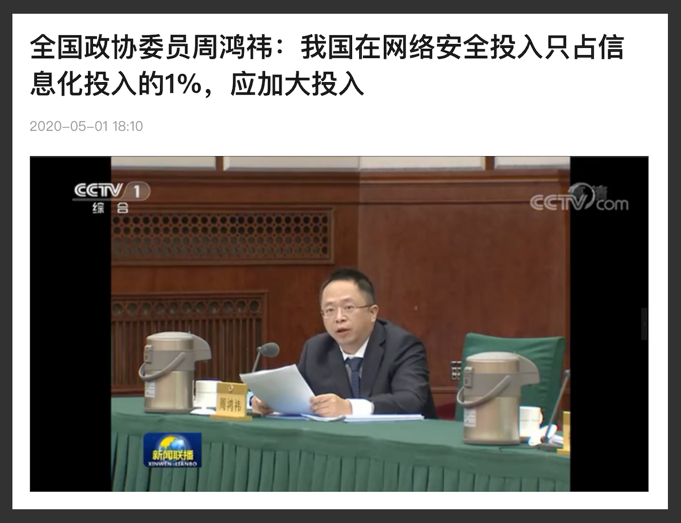

Tuber was developed by Shanghai Fengxuan Information Technology Co., Ltd., in which Qihoo 360, the Beijing-based cybersecurity firm founded by entrepreneur Zhou Hongyi, holds a 70 percent stake. Zhou, currently the chairman and CEO of Qihoo 360 Group, is a delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), China’s top political advisory body. Speaking at a May meeting in his capacity as an official delegate, Zhou spoke of the need for China to invest more heavily in cybersecurity, and his speech was featured on China Central Television’s nightly newscast.

Zhou has defended and aided efforts at information control. Writing in 2014 for China Press and Publishing Journal, Zhou defended the leading role of party-state media to steadily raise “the discourse power and influence of mainstream news media in the main positions of the internet.”

In short, Zhou appears to enjoy close proximity to the Chinese government, making it unlikely that Tuber was launched without the government’s blessing. The app, moreover, had approval from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. According to the MIIT’s online database of Internet Content Providers (ICPs), Fengxuan Information Technology received government approval for Tuber on Oct. 9, shortly before the app’s official release.

This leaves us with the million-dollar question: Why would an app that enables users to bypass the Great Firewall be permitted at all? What possible strategic interest could China’s leadership have in allowing the download and use of a tool that apparently allows circumvention of the world’s most sophisticated system of internet controls?

The likely answer is that Tuber may be a step toward transforming the nature of Chinese access to the global internet, moving from a period of walls and circumvention (through unauthorized VPNs) to a period of controlled and “guided” access. The CCP leadership may recognize the need for a new era of more flexible information management, allowing Chinese internet users access beyond the reaches of the Great Firewall, while at the same time maintaining a decisive level of control over information the regime regards as threatening.

It should be obvious that flexibility does not mean openness—as Tuber’s short-lived trial demonstrates. Improvements in filtering and control technologies may enable the CCP to permit greater cyber engagement globally on its own terms. And the advantages of this from the vantage point of the Chinese leadership are three-fold.

First, greater flexibility enables the CCP to respond to demand inside China for greater access to the global internet, particularly from younger professionals. In fact, Tuber is not the first tool to offer such access. Launched in January this year, an app called “Weixing Search” advertised itself as a “cross-border browser” that allowed users to bypass the Great Firewall to access some content on platforms such as YouTube and Instagram. Revealingly, one review of “Weixing Search,” cross-posted on the website of China Daily, a newspaper published by the Chinese government, began with a unique selling proposition focused on Chinese youth. “As ideas in our time steadily advance, the desire and demand for searching the world grows steadily among the new generation of young people,” it said. The article included a screenshot of Google Scholar, a site blocked in China that would be a valuable resource for students requiring access to international scholarship in various disciplines.

Second, the release of a restricted search tool for the global internet could, despite Zhao Lijian’s denials, serve a diplomatic purpose, particularly as China faces international pressure over digital protectionism. An app giving Chinese internet users access to platforms outside the Great Firewall would help China make the case that it does not shut out foreign competitors, even as certain content and search activity remains highly restricted. Leaders and diplomats might argue that China has not restricted access wholesale and indiscriminately, but is merely upholding local laws.

Finally, a tool like Tuber might facilitate the representation of China’s official interests and positions overseas, beyond the Great Firewall. Unlike the Great Firewall’s strategy of blocking outright designated overseas websites, an app like Tuber might conduct finer, more localized tracking and controlling of user behavior. This might allow China’s so-called “Little Pinks,” the online nationalists who have in the past launched attacks on foreign sites and accounts, to express their viewpoints on platforms otherwise banned.

Although Tuber was ultimately pulled down, the fact that it was ever allowed at all is significant. In an era of porous but effectively policed access, Tuber’s brief existence suggests the Great Firewall could be replaced by the Great Filter. Such a system would require careful engineering to ensure that the CCP is able to monitor the global internet effectively, in a way that suits the regime’s interests both domestically and internationally. If China builds out such a system, the ultimate legacy of Tuber will lie in the glimpse it offered of the future to come.

David Bandurski is the co-director of the China Media Project, a research program in partnership with the Journalism & Media Studies Center at the University of Hong Kong.

Facebook, Google, and Twitter provide financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

Commentary

A brief experiment in a more open Chinese web

November 12, 2020