INTRODUCTION

Afghan politics are in a troubled state and may well represent the chief threat to the current stabilization effort.

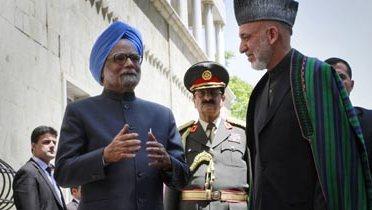

Disputes over the results of the September 2010 parliamentary elections, and disagreements over who should resolve those disputes, have continued well into 2011 and in fact are not fully settled as of this writing.[1] The August 2009 presidential election was marred by fraud and other irregularities. The fallout of the ensuing process continues to burden U.S.-Afghan relations in particular to this day. According to the Kabul-based Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, an independent research organization, in the eyes of most Afghans, “elections are being used to legitimize or ‘rubber stamp’ the control of the powerful,” and “elections are compounding a distrust of institutions.”[2] Meanwhile President Karzai must constitutionally leave office in 2014. The weakness of political movements and parties in Afghanistan, together with the relative strength of patronage networks and the threat of ethnic conflicts, augur poorly for the prospects of the competition to succeed him.

The United States and its NATO partners, in conjunction with Afghan security forces, have a fairly detailed and comprehensive military strategy for the Afghan campaign. It entails a prioritization and sequencing of major efforts in certain districts and provinces of the country, with several phases in place, and a clear set of parameters to determine how and when to hand off responsibility to Afghan army and police forces over time. The training and equipping schedule for the Afghan security forces is detailed, thorough, and carefully juxtaposed with the campaign plan for foreign forces. The chain of command within NATO for this effort is clear, and coordination with relevant Afghan partner agencies is generally professional and amicable.

There is no such international political strategy for working with Afghanistan and its government.[3] To be sure, some general notions are clear. The international community seeks a viable, legitimate, and proficient Afghan government able to enjoy the support of its people, improve their well being, and gradually take over responsibility for the country’s security. But these are generalities. The military strategy goes well beyond such amorphous visions to a specific set of actions and a detailed sequencing of effort. There is no comparable roadmap on matters of politics.

The various agencies working in Afghanistan have their discrete goals. They also are pursuing many individually worthy programs, including those of USAID, the United Nations Assistance Mission, and various other foreign missions. A great deal of good work is being done by dedicated, gifted people of all nationalities including, of course, Afghans. But these individual efforts are not adequately informed by broad political strategy or sufficiently focused on the crucial period of the next two to three years. The country overall has a national development strategy too—but these concern matters of development and government capacity, not politics. Put differently, the international community does not have an adequate plan to help Afghanistan develop the institutions and processes needed to improve the way disputes are settled and issues resolved through peaceful, legal means, especially in the immediate future when progress is needed to defeat the insurgency. There is a general hope that the 2005 constitution, and existing structures such as they exist, will suffice—or that any necessary corrections and improvements will be taken care of by Afghans.

[1] See International Crisis Group, “Afghanistan’s Elections Stalemate,” Kabul, Afghanistan, February 23, 2011, available at http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/asia/south-asia/afghanistan/B117-afghanistans-elections-stalemate.aspx [accessed March 24, 2011].

[2] Noah Coburn and Anna Larson, “Undermining Representative Governance: Afghanistan’s 2010 Parliamentary Election and Its Alienating Impact,” Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, Kabul, Afghanistan, February 2011, available at http://www.areu.org.af/ [accessed March 17, 2011].

[3] For a corroborating view, see for example Thomas Barfield and Neamatollah Nojumi, “Bringing More Effective Governance to Afghanistan: 10 Pathways to Stability,” Middle East Policy, vol. 17, no. 4 (Winter 2010), pp. 45-46.