Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

The People’s Republic of China has shaped the U.S.-India relationship since it came into existence in 1949. Fifty five years ago, for example, a senator from Massachusetts argued that there was a “struggle between India and China for the economic and political leadership of the East, for the respect of all Asia, for the opportunity to demonstrate whose way of life is the better.” He asserted that it was crucial that the U.S. help India win that contest with China. A few months later, that senator would be elected president. The man he defeated, Richard Nixon, had earlier also highlighted the importance of the U.S. helping India to succeed in the competition between the “two great peoples in Asia.” This objective was made explicit in Eisenhower and Kennedy administration documents, which stated that it was in American national interest to strengthen India—even if that country wasn’t always on the same page as the U.S.

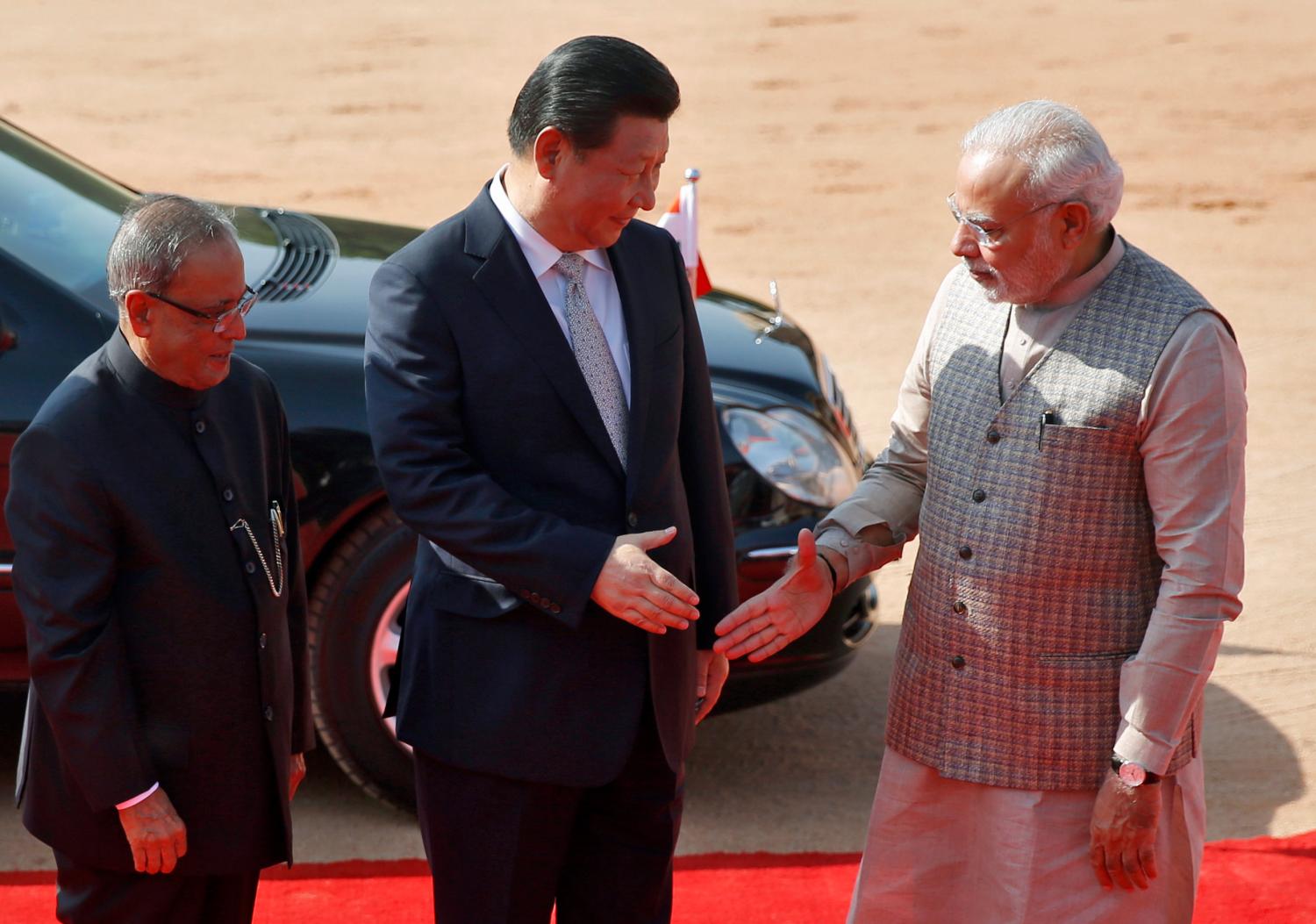

Today, both India and the U.S. have relationships with China that have elements of cooperation, competition and, potentially, conflict—though in different degrees. Each country has a blended approach of engaging China, while preparing for a turn for the worse in Chinese behavior. Each sees a role for the other in its China strategy. Each thinks a good relationship with the other sends a signal to China, but neither wants to provoke Beijing or be forced to choose between the other and China.

Each also recognizes that China—especially uncertainty about its behavior—is partly what is driving the India-U.S. partnership. Arguably, there have been three imperatives in the U.S. for a more robust relationship with India and for supporting its rise: strategic interest, especially in the context of the rise of China; economic interest; and shared democratic values. Indian policymakers recognize that American concerns about the nature of China’s rise are responsible for some of the interest in India. New Delhi’s own China strategy involves strengthening India both security-wise and economically (internal balancing) and building a range of partnerships (external balancing)—and it envisions a key role for the U.S. in both. Some Indian policymakers highlight another benefit of the U.S. relationship: Beijing takes Delhi more seriously because Washington does.

But India and the U.S. also have concerns about the other when it comes to China. Both sides remain uncertain about the other’s willingness and capacity to play a role in the Asia-Pacific.

Additionally, Indian policymakers worry both about a China-U.S. condominium (or G-2) and a China-U.S. crisis or conflict. There is concern about the reliability of the U.S., with the sense that the U.S. will end up choosing China because of the more interdependent Sino-American economic relationship and/or leave India in the lurch.

Some in the U.S. also have reliability concerns about India. They question whether the quest for “strategic autonomy” will allow India to develop a truly strategic partnership with the U.S. There are also worries about the gap between Indian potential and performance. Part of the rationale for supporting India’s rise is to help demonstrate that democracy and development aren’t mutually exclusive. Without delivery, however, this rationale—and India’s importance—fades away.

As things stand, neither India nor the U.S. is interested in the other’s relationship with China being too hot or too cold—the Goldilocks view. For New Delhi, a too-cosy Sino-U.S. relationship is seen as freezing India out and impinging on its interests. It would also eliminate one of Washington’s rationales for a stronger relationship with India. A China-U.S. crisis or conflict, on the other hand, is seen as potentially destabilizing the region and forcing India to choose between the two countries. From the U.S. perspective, any deterioration in Sino-Indian relations might create instability in the region and perhaps force it to choose sides. Too much Sino-Indian bonhomie, on the other hand, would potentially create complications for the U.S. in the bilateral, regional and multilateral spheres.

However, both India and the U.S. do share an interest in managing China’s rise. Neither would like to see what some have outlined as President Xi Jinping’s vision of Asia, with a dominant China and the U.S. playing a minimal role. India and the U.S. recognize that China will play a crucial role in Asia—it is the nature of that role that concerns both countries. Their anxiety has been more evident since 2009, leading the two sides to discuss China—and the Asia-Pacific broadly—more willingly. They have an East Asia dialogue in place. There is also a trilateral dialogue with Japan and talk of upgrading it to ministerial level and including Japan on a more regular basis in India-U.S maritime exercises.

The Obama administration has also repeatedly stated that it sees India as part of its “rebalance” strategy. In November 2014, President Obama, speaking in Australia, stressed that the U.S. “support[ed] a greater role in the Asia Pacific for India.” The Modi government, in turn, has made the region a foreign policy priority. Prime Minister Modi has implicitly criticized Chinese behavior in the region (and potentially in the Indian Ocean), with his admonition about countries with “expansionist mindsets” that encroach on others’ lands and seas. In a departure from its predecessor, his government has shown a willingness to express its support for freedom of navigation in the South China Sea in joint statements with Vietnam and the U.S. In an op-ed, the prime minister also stated that the India-U.S. partnership “will be of great value in advancing peace, security and stability in the Asia and Pacific regions…” and, in September, President Obama and he “reaffirm[ed] their shared interest in preserving regional peace and stability, which are critical to the Asia Pacific region’s continued prosperity.”

Recommendations

• India and the U.S. should continue to strengthen their broader relationship (and each other); this will, in and of itself, shape China’s perception and options. But they should also continue to engage with Beijing—this can benefit all three countries and demonstrate the advantages of cooperation.

• The two countries should continue their consultations on China. The need to balance the imperatives of signaling Beijing, while not provoking it might mean that publicly India and the U.S. continue to couch these official discussions in terms of the Asia-Pacific (or sometimes the Indo-Pacific), but privately the dialogue needs to be more explicit. Both countries’ regional strategies aren’t all about China, but it features significantly—a fact that needs to be acknowledged.

This dialogue should be consistent and not contingent on Chinese behavior during a given quarter. It should perhaps include contingency planning. It might also be worth expanding or upgrading this dialogue beyond the foreign policy bureaucracies. In addition, there should be consideration of bringing in other like-minded countries, like Australia and Japan. Furthermore, the two countries can also consult on the sidelines of—or prior to—regional summits.

• The U.S. should continue to support the development of India’s relationships with its allies and countries in Southeast Asia. But while nudging and, to some extent participating in, the development of these ties, Washington should let them take shape organically. Relationships driven by—and seen as driven by—Delhi and Tokyo or Delhi and Canberra will be far more sustainable over the long term rather than partnerships perceived as driven by the U.S.

• New Delhi, in turn, has to show that it can walk the talk and follow through on its “Act East” policy—deepening both strategic and economic cooperation with the region. It will also need to move beyond its traditional aversion to all external powers’ activity in South Asia and consider working with the U.S. on shaping the strategic and economic options available to India’s neighbors (whose relations with China have expanded).

• There can be learning about China, including its domestic dynamics and actors, as well as perceptions and policies about it in the other country—and not just on the part of the governments. To the extent that competitive instincts will allow, the American and Indian private sectors, for example, can discuss doing business in China, perhaps learning from each other’s experiences. Or they can do this in the context of a Track-II India-U.S. dialogue about China that involves other stakeholders.

• There should also be consideration of an official China-India-U.S. trilateral dialogue, which could serve at least two purposes: provide a platform to discuss issues of common concern and show Beijing that India and the U.S. aren’t interested in excluding it if it is willing to be part of the solution. It can also help allay Indian concerns about being left out of a “new kind of major power relationship” between the other two countries.

When it comes to China, however, India and the U.S. must have realistic expectations about the other. Every decision each country makes vis-à-vis China should not be seen as a zero-sum game. India shouldn’t expect to be treated as an ally (with all the assurances that come with that) if it isn’t one. And the U.S. has to recognize that India is likely to maintain other partnerships in its attempt to balance China—including one with Russia—that Washington might not like. Finally, it is important for policymakers and analysts in both countries to keep in mind that an India-U.S. strategic partnership solely based on China is neither desirable nor sustainable.