The following is one of eight briefs commissioned for the 16th annual Brookings Blum Roundtable, “2020 and beyond: Maintaining the bipartisan narrative on US global development.”

Addressing today’s massive global education crisis requires some disruption and the development of a new 21st-century aid delivery model built on a strong operational public-private partnership and results-based financing model that rewards political leadership and progress on overcoming priority obstacles to equitable access and learning in least developed countries (LDCs) and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs). Success will also require a more efficient and unified global education architecture. More money alone will not fix the problem. Addressing this global challenge requires new champions at the highest level and new approaches.

Key data points

In an era when youth are the fastest-growing segment of the population in many parts of the world, new data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) reveals that an estimated 263 million children and young people are out of school, overwhelmingly in LDCs and LMICs.1 On current trends, the International Commission on Financing Education Opportunity reported in 2016 that, a far larger number—825 million young people—will not have the basic literacy, numeracy, and digital skills to compete for the jobs of 2030.2 Absent a significant political and financial investment in their education, beginning with basic education, there is a serious risk that this youth “bulge” will drive instability and constrain economic growth.

Despite progress in gender parity, it will take about 100 years to reach true gender equality at secondary school level in LDCs and LMICs. Lack of education and related employment opportunities in these countries presents national, regional, and global security risks.

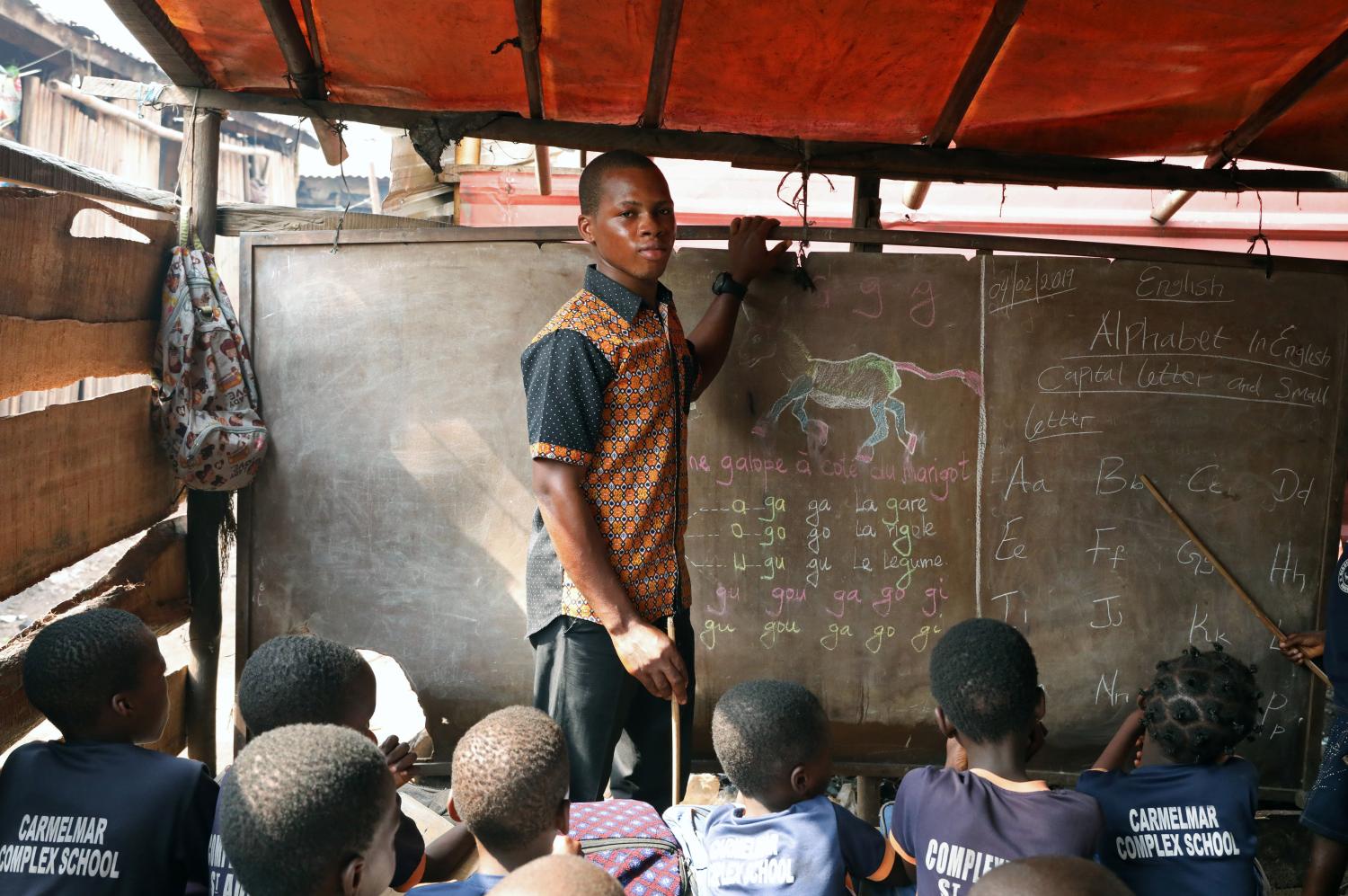

Among global education’s most urgent challenges is a severe lack of trained teachers, particularly female teachers. An additional 9 million trained teachers are needed in sub-Saharan Africa by 2030.

Refugees and internally displaced people, now numbering over 70 million, constitute a global crisis. Two-thirds of the people in this group are women and children; host countries, many fragile themselves, struggle to provide access to education to such people.

Highlighted below are actions and reforms that could lead the way toward solving the crisis:

- Leadership to jump-start transformation. The next U.S. administration should convene a high-level White House conference of sovereign donors, developing country leaders, key multilateral organizations, private sector and major philanthropists/foundations, and civil society to jump-start and energize a new, 10-year global response to this challenge. A key goal of this decadelong effort should be to transform education systems in the world’s poorest countries, particularly for girls and women, within a generation. That implies advancing much faster than the 100-plus years required if current programs and commitments remain as is.

- A whole-of-government leadership response. Such transformation of currently weak education systems in scores of countries over a generation will require sustained top-level political leadership, accompanied by substantial new donor and developing country investments. To ensure sustained attention for this initiative over multiple years, the U.S. administration will need to designate senior officials in the State Department, USAID, the National Security Council, the Office of Management and Budget, and elsewhere to form a whole-of-government leadership response that can energize other governments and actors.

- Teacher training and deployment at scale. A key component of a new global highest-level effort, based on securing progress against the Sustainable Development Goals and the Addis 2030 Framework, should be the training and deployment of 9 million new qualified teachers, particularly female teachers, in sub-Saharan Africa where they are most needed. Over 90 percent of the Global Partnership for Education’s education sector implementation grants have included investments in teacher development and training and 76 percent in the provision of learning materials.

- Foster positive disruption by engaging community level non-state actors who are providing education services in marginal areas where national systems do not reach the population. Related to this, increased financial and technical support to national governments are required to strengthen their non-state actor regulatory frameworks. Such frameworks must ensure that any non-state actors operate without discrimination and prioritize access for the most marginalized. The ideological divide on this issue—featuring a strong resistance by defenders of public education to tap into the capacities and networks of non-state actors—must be resolved if we are to achieve a rapid breakthrough.

- Confirm the appropriate roles for technology in equitably advancing access and quality of education, including in the initial and ongoing training of teachers and administrators, delivery of distance education to marginalized communities and assessment of learning, strengthening of basic systems, and increased efficiency of systems. This is not primarily about how various gadgets can help advance education goals.

- Commodity component. Availability of appropriate learning materials for every child sitting in a classroom—right level, right language, and right subject matter. Lack of books and other learning materials is a persistent problem throughout education systems—from early grades through to teaching colleges. Teachers need books and other materials to do their jobs. Consider how the USAID-hosted Global Book Alliance, working to address costs and supply chain issues, distribution challenges, and more can be strengthened and supported to produce the model(s) that can overcome these challenges.

Annual high-level stock take at the G-7. The next U.S. administration can work with G-7 partners to secure agreement on an annual stocktaking of progress against this new global education agenda at the upcoming G-7 summits. This also will help ensure sustained focus and pressure to deliver especially on equity and inclusion. Global Partnership for Education’s participation at the G-7 Gender Equality Advisory Council is helping ensure that momentum is maintained to mobilize the necessary political leadership and expertise at country level to rapidly step up progress in gender equality, in and through education.3 Also consider a role for the G-20, given participation by some developing country partners.

-

Footnotes

- “263 Million Children and Youth Are Out of School.” UNESCO UIS. July 15, 2016. http://uis.unesco.org/en/news/263-million-children-and-youth-are-out-school.

- “The Learning Generation: Investing in education for a changing world.” The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity. 2016. https://report.educationcommission.org/downloads/.

- “Influencing the most powerful nations to invest in the power of girls.” Global Partnership for Education. March 12, 2019. https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/influencing-most-powerful-nations-invest-power-girls.