Abstract

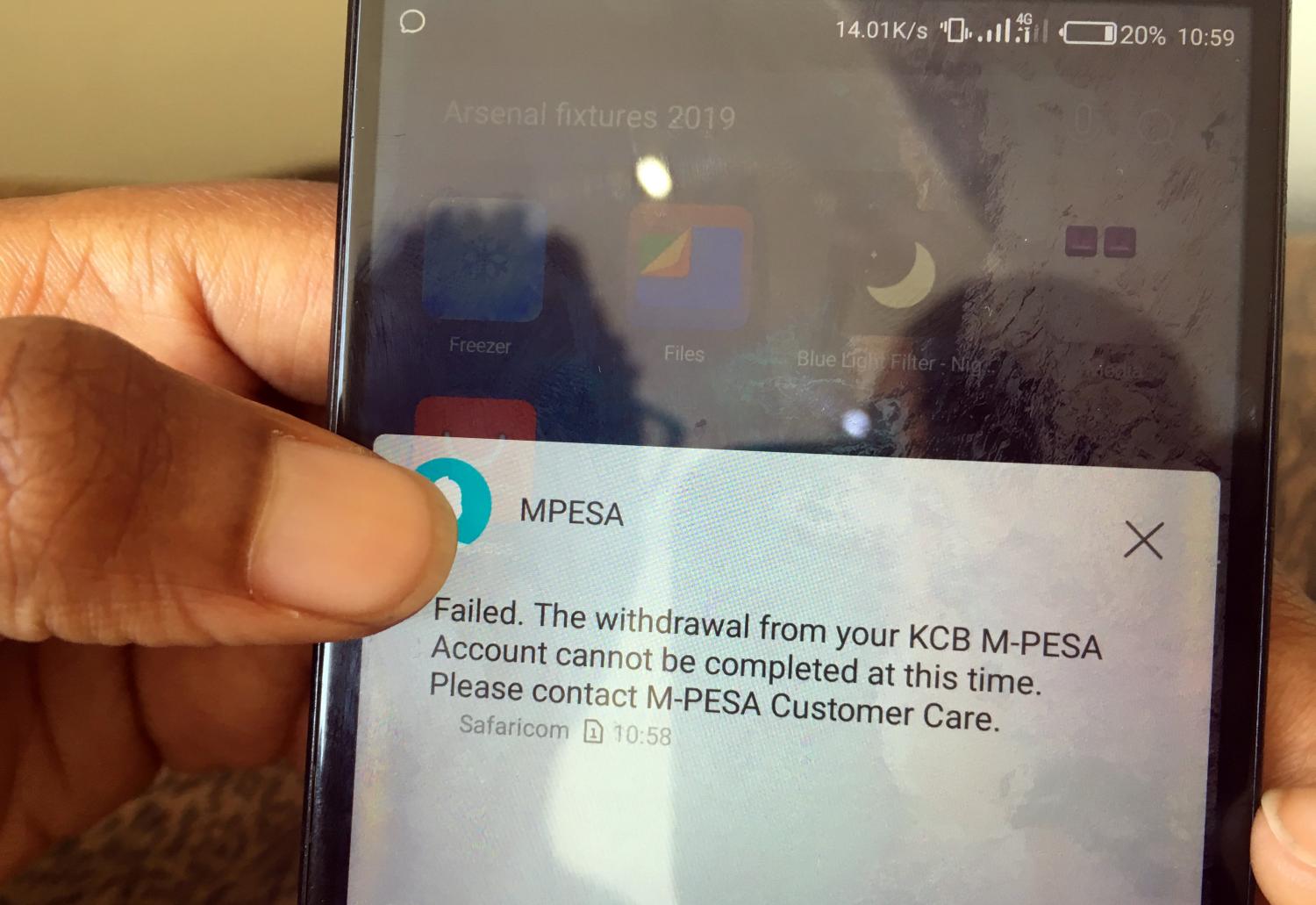

Taxation on mobile phone-based transactions and on airtime has been introduced in Kenya and is spreading to other African countries. Some countries in sub-Saharan Africa view mobile phones as a booming subsector easy to tax due to the increasing turnover of transactions and the formal nature of such transactions by both formal and informal enterprises. The increasing tax burden on the subsector and the consumers, though, has raised concerns that the massive gains made in financial inclusion in developing countries made possible by retail electronic payments platform via mobile phone transactions may be reversed—resulting in a return to cash transactions. In addition to a 2003 excise tax on airtime, since 2013, Kenya has introduced and reworked taxes on goods such as mobile phones, computer hardware, software, and, more recently, retail financial transactions. The most recent adjustments in taxation in the Finance Act 2018 increased the excise tax on money transfer services by banks from 10 percent to 20 percent, on telephone services (airtime) from 10 percent to 15 percent, on mobile phone-based financial transactions from 10 percent to 12 percent, and introduced a 15 percent excise tax on internet data services and fixed-line telephone services.

This paper shows that taxation on mobile phone airtime and financial transactions may not expand the tax base significantly but, rather, may reverse the gains on retail electronic payments and financial inclusion. A higher tax rate on low-level retail electronic transactions mostly levied on low-income earners that are sensitive to transaction costs may discourage the use of mobile phone-based transactions, incentivizing them to revert to cash transactions to evade taxes and so less tax revenue. This trend will deal a big blow to the financial inclusion success witnessed so far.

Poorly designed tax policy will have poor outcomes on tax revenue and market distortions will drive consumption behavior on an undesired path, so any future review of excise tax rates on airtime and financial services should be preceded with a thorough analysis of optimal taxation excise taxes, the likely change in behavior around financial services, and, above all, the marginal contribution to the tax effort that policy aims to raise. The data so far available shows that the contribution of mobile money-related taxes is less than 1 percent of total tax revenue, a negligible contribution to Kenya’s total tax income, at high economic costs. These lessons are not just relevant for Kenya but also for other countries in Africa with such tax propositions. Introducing and increasing taxes on mobile phone transactions may risk stalling progress on digitization and fiscal policy design as well as revenue administration.

Download the full policy brief