Content from the Brookings-Tsinghua Public Policy Center is now archived. Since October 1, 2020, Brookings has maintained a limited partnership with Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management that is intended to facilitate jointly organized dialogues, meetings, and/or events.

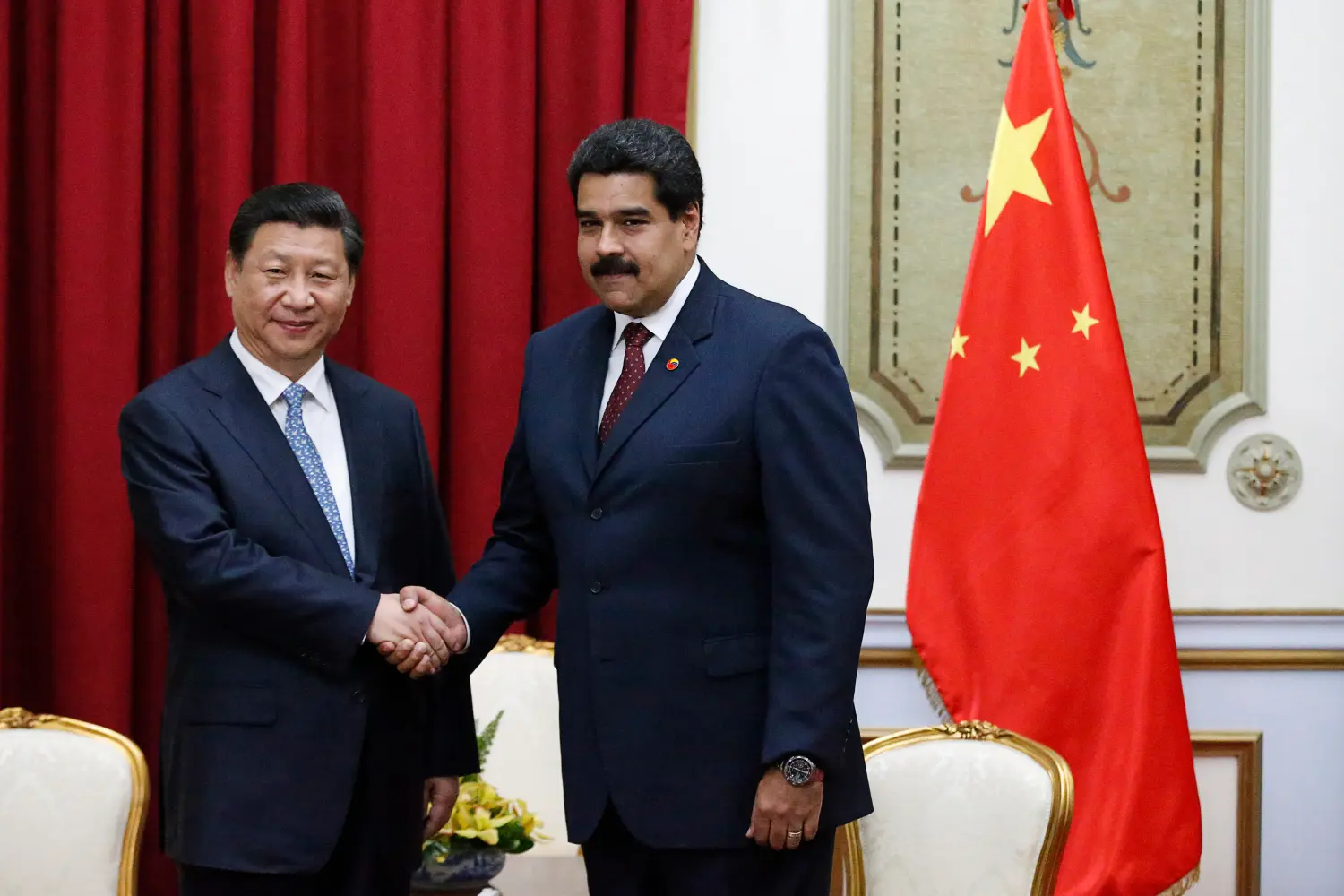

China’s trade, investment, and loans to Latin America have grown remarkably since 2000. From almost negligible amounts, trade with China now constitutes approximately 13 percent of the region’s total global trade, further supplemented by favorable loans and investment in a variety of sectors. China has expanded its diplomatic representation, military exchanges, and cultural presence throughout Latin America as well. This has enabled it to become an alternative to traditional Western sources of investment, trade, and technology, thereby providing new options (and greater autonomy) for Latin American states.

China’s trade, investment, and loans to Latin America have grown remarkably since 2000. From almost negligible amounts, trade with China now constitutes approximately 13 percent of the region’s total global trade, further supplemented by favorable loans and investment in a variety of sectors. China has expanded its diplomatic representation, military exchanges, and cultural presence throughout Latin America as well. This has enabled it to become an alternative to traditional Western sources of investment, trade, and technology, thereby providing new options (and greater autonomy) for Latin American states.

However, the growth of China’s economic role in the region has also drawn criticism. The rapid increase in China’s engagement has raised concerns that it could enable or pressure Latin American countries to erode gains made on labor, environmental, and human rights in an effort to promote a more favorable business environment for Chinese companies. Others have raised the concern that China’s influence over Latin American governments may have negative geopolitical consequences for the United States, possibly even posing a national security threat.

Harold Trinkunas assesses how economic relations between China and Latin America—particularly trade, investment, and loans from China to Latin American countries—affects China’s ability to influence domestic politics in the Western Hemisphere. He concludes that:

- The scope for Chinese leverage on Latin American governments is limited to a small set of countries, e.g. those with limited access to international financial markets;

- Economic relationships with China enabled governments in the region to pursue their preferred policies more aggressively—but this proved true in countries with good governance environments as much as those with poor governance environments; and

- Even if China does enable governments or actors that erode democracy, human rights, and rule of law, the choices were typically made domestically rather than as a consequence of direct Chinese pressure.