Last week, I wrote about the “mismatch” hypothesis, which posits that the beneficiaries of affirmative action in higher education will not be able to keep up in a demanding environment and would in fact be better off had they not been given a leg up in the admissions process. I showed that there is no credible evidence supporting the mismatch theory, and that the opposite finding prevails: students are most likely to graduate by attending the most selective institution that will admit them.

The focus of my analysis last week was a November 2012 NBER working paper by a team of economists from Duke University using data from the University of California Office of the President (UCOP). I conducted a reanalysis of the UCOP data and showed that more appropriate methods yield findings that are not consistent with the mismatch hypothesis.

Last month, three of the four authors of the earlier study released a new NBER working paper on the effects of mismatch on the chances that students, especially underrepresented minorities, will graduate with science degrees. In other words, instead of looking at overall graduation rates as they did in the earlier paper, they focused on earning a degree in the sciences. The new paper claims to find strong evidence that students with weaker academic preparation are much more likely to be successful at a lower-ranked campus: “Our estimates suggest that the vast majority of minority students who begin in the sciences at UC Berkeley would be more likely to graduate with a science degree had they enrolled in a less-selective campus.”

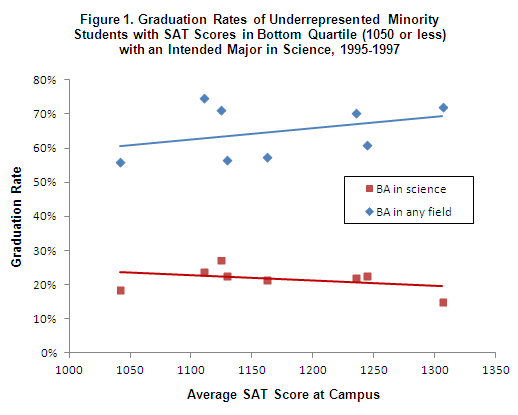

Do the findings of the new paper hold up to careful scrutiny any better than the findings of the previous paper? Only marginally. Figure 1 shows the graduation rates, both in the sciences and overall, for underrepresented minority students who intended to major in the sciences and had SAT scores that placed them in the bottom quarter of all UC applicants (1050 or less) in the period before California banned affirmative action. Students in this group that attended a more selective university were slightly more likely to graduate with a degree in any field (as would be expected based on last week’s analysis), but slightly less likely to graduate with a degree in the sciences.

Is this finding the result of affirmative action? The authors of the February 2013 NBER paper argue that it is: “in a period when racial preferences in admissions were strong, minority students were in general over-matched, resulting in low graduation rates in the sciences… In contrast, non-minority students are generally well-placed for graduating in the sciences.”

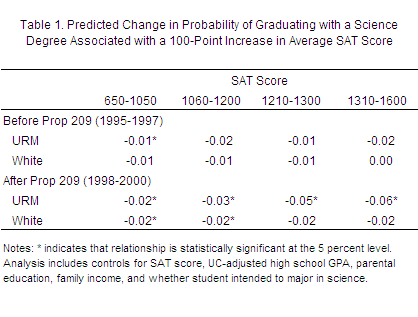

But a closer look at the UCOP data casts serious doubt on this conclusion. Table 1 shows the relationship between campus selectivity and graduation rates in the sciences for different groups of students. Specifically, I calculate the expected increase in the chance that a student will earn a degree in the sciences associated with a 100-point increase in the average SAT score of the campus, controlling for the student’s SAT score, high school GPA, parental education, and family income. I do not use the problematic Dale-Krueger method used by the NBER paper’s authors for the reasons I discussed last week. Following the authors’ practice of separating out students by whether they intended to major in the sciences cuts the data very thin and results in very imprecise (and non-robust) estimates, so I combine all students together but control for whether each student indicated an intention to major in the sciences.

The upper-left number in Table 1 indicates that, prior to the affirmative action ban, URM students with the lowest SAT scores were about one percentage point less likely to graduate with a degree in the sciences if they attend a more selective campus. This is similar to what we saw in Figure 1. The relationship is similar for URM students in the upper three SAT quartiles and for white students in all but the top quartile, although those relationships are estimated less precisely and consequently we cannot confidently reject the possibility that there is no relationship between science graduation rates and selectivity for those groups.

If affirmative action were the reason for the slight negative relationship between selectivity and science graduation rates for URM students, then we would expect the relationship to go away in the period following the passage of Prop 209, which banned affirmative action in California. But Table 1 shows exactly the opposite finding: the negative relationship was substantially larger in the three-year period following the ban, for both URM and white students. And the relationship was strongest for the most highly qualified URM students in the period following Prop 209.

A simple before-and-after comparison should not be taken as definitive, as other factors could have changed between the 1995-1997 and 1998-2000 periods. But the pattern of results casts doubt on the idea that affirmative action was the driver behind the 1995-1997 results given that even stronger negative relationships appear in the 1998-2000 data.

The fact still remains that some students are slightly more likely to graduate with a science degree if they attend a less selective university, although it is unclear to what extent this relationship is biased by unobserved student characteristics.[1] But in any case, it’s unclear what to make of this finding given that overall graduation rates go in the opposite direction. Is it better to have a higher chance of persisting in the sciences if it is accompanied by an increased risk of dropping out altogether? And is it better to have a science degree from a lower-ranked school rather than a non-science degree from an elite campus such as Berkeley or UCLA?

There is no doubt that graduation rates, both in the sciences and overall, are too low, especially for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Anyone who thinks the U.S. needs to increase the number of students who earn science degrees should be troubled by the high percentages of students who start out interested in science but end up switching to another field or dropping out. Persisting in the sciences is especially challenging for students with weak academic preparation. Figure 1 shows success rates of around 20 percent for low-scoring URM students, a stubbornly low rate that doesn’t vary much by campus.

Policymakers and higher education practitioners clearly need to seek ways to increase the student success in the sciences. But redirecting students to less demanding institutions, either through changes to admissions policies or college counseling practices, is a dubious strategy that at best increases success rates in science by small margins at the cost of increased dropout rates overall.

[1] The negative relationship becomes stronger when control variables are added. If sorting on unobserved characteristics occurs in the same direction as the observed characteristics, then the true (causal) relationship will be larger in magnitude than the estimated relationship.