Part 3 of “Baked in and Wired: eDiplomacy @ State”

| « Read Part 2: The History of eDiplomacy at State |

Read Part 4: Internet Freedom » |

“Our basic assumption is that we’ve all lost control of the information environment—the only option is to embrace the change and work to shape it.”

—Ben Scott, Innovation Adviser to Hillary Clinton

What’s the Issue?

One of Australia’s foremost foreign policy thinkers, Allan Gyngell , (Director-General of the Office of National Assessments), recently set out why public diplomacy increasingly matters. He argued, “We are now entering a period in which diplomacy will matter again more than it has since the mid-20th century and the beginning of the Cold War. And…it will be a more complex and challenging form of diplomacy, with more than the usual scope for success and failure.” Gyngell goes on to list four reasons why, the fourth of which he describes as follows:

The final reason diplomacy will matter more is that its objects—the entities it is trying to influence—are increasing in number as the deeper effects of the information revolution, especially new forms of social media, spread through societies.

Just as the circumscribed court politics of the eighteenth century gave rise to the more complex diplomacy of the nation state in the nineteenth century, and the new dimensions of multilateral diplomacy were added in the twentieth century, in the twenty first century an additional dimension of public diplomacy is needed to address the publics which increasingly shape state behavior.

As Joseph Nye says, “in the information age, it’s not just whose army wins but whose story wins”. And diplomats are storytellers. The first of them in the Greek city states were actors. They’ve never looked back.

The technology-driven changes affecting public diplomacy have produced both risks and opportunities for foreign ministries. These include:

- The opportunity to influence and speak directly and more frequently to large audiences, which will in turn feed into political influence. In the case of State, this involves its emergence as a de facto media empire.

- The opportunity to segment audiences and target messages to key groups.

- Broadening awareness among diplomats of political and social movements that are driven from the bottom up by providing an early warning capability.

- The chance to listen to voices and receive information previously unavailable to diplomats. With the new opportunity to access the views of so many people on so many topics all the time it should help good listeners to better understand the complexity of politics, society, and culture beyond the elite views represented in traditional diplomatic sources.

- The risk of economically costly damage to a country’s reputation or key exports in incredibly short time-frames.

- The challenge of competing for a voice when everyone can communicate and, in some cases, with individuals or organizations that are more successful at controlling a foreign policy message than governments.

At the core of this change has been the democratization of access to communications tools as well as the nature of that communication. Most people on earth now have access to a cell phone. The International Telecommunications Union estimates there are six billion of them, with a global penetration rate of 87 percent, including 79 percent in the developing world. Even in countries like Haiti—one of the world’s poorest with per capita GDP of just $1,300 in 2011—there are 41 mobile phone subscriptions per 100 people.

Giving nearly the entire human populace access to voice and SMS communication is a radical development—the first time everyone on earth has at least theoretically been one phone call away from someone else. This is, of course, hypothetical; it is reasonably hard to obtain another person’s cell phone number unless they give it to you. But increasingly, phones are not limited to voice and SMS capability (as powerful as these can be). Estimates are that there are now around one billion smart phones that have the capacity to access the internet to some extent, with the take-up of these phones spreading rapidly as costs plummet. That is facilitating access to an even greater reservoir of information. It is also providing access to networked social media platforms that, for some individuals, can dramatically multiply their reach. The largest of these networks is Facebook, which had 955 million monthly active users at the end of June 2012, and which, in 2012, became the largest tech IPO in history with a valuation in excess of $100 billion.

For foreign ministries, connection technologies have ushered in three big changes: changing hierarchies and new actors; real time diplomacy; and rapid brand damage.

Hierarchies and New Actors

This new, networked communication facilitated by the cell phone is changing the way people communicate and old power hierarchies in the process. Secretary Clinton’s Senior Advisor for Innovation, Alec Ross characterized this shift in the following way:

So I think that part of what connection technologies do, is they take power away from the nation state and large institutions and give it to individuals and small institutions. And so very big companies and very big governments are often times those which are most roiled, which are most disrupted, by connection technologies. Because what it does is it puts power in the hands of individuals that was previously unimaginable. And this can be for both good or ill. Technology itself is value neutral. It takes on the values and intentions of the users.

These remarks came just a few months into the Arab Spring. But other events have also led governments and business to reassess the potential of connection technologies.

Another illustration of the power of these tools to disrupt the foreign policy establishment came with the launch of the Kony2012 video by Invisible Children. This previously obscure NGO reported its support and revenue as less than $14 million in financial year 2010-11. Despite this relatively modest footprint, its half-hour video on Joseph Kony, leader of the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda, was launched in March 2012 and quickly amassed over 100 million views.

Unsurprisingly, the group’s success irked just about everyone. The Ugandan government was aghast that a global LRA narrative was being shaped by an upstart NGO. Others were quick to point out factual errors in the film or the way Invisible Children spent its funds.

Used under a creative commons license, PipPipHooray1

Used under a creative commons license, PipPipHooray1

From the perspective of global perceptions about Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army, these criticisms were beside the point. Invisible Children’s narrative had spread so pervasively, no level of retrospective scrutiny was going to change the now preponderant narrative it had shaped.

In the Kony 2012 video, Invisible Children claim credit for getting around 100 U.S. military advisers deployed to Africa to help in the hunt for Kony but expressed concern that without political pressure they risked being withdrawn. It was a reasonable worry given Obama administration officials had told the House Foreign Affairs Committee in October that the deployment would be “short-term.” After Invisible Children’s viral campaign, it didn’t take long for President Obama to address the group’s concern directly. Just days after its “Cover the Night” action, President Obama announced during a speech at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum that “our advisers will continue their efforts to bring this madman [Joseph Kony] to justice and to save lives.”

This is not to suggest that every individual and NGO around the world is suddenly going to be sending governments off on a string of populist sprees addressing their pet priorities. Invisible Children had a strong global network established well in advance of the release of the Kony2012 video, which no doubt helped its roll-out. It will also likely be harder for would-be imitators to replicate its success easily. But connection technologies have discernibly empowered some individuals and groups, and they are now going to be playing themselves into foreign policy decisions whether foreign ministries like it or not.

Real Time Diplomacy

“I kid my good friend, Henry Kissinger. Can you imagine in a world of Twitter, being able to sneak out of Pakistan and fly to China and do secret negotiations? It’s just an entirely different 24/7 public environment that you are living in.”

—Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, March 2012

The diffusion of cell phones across the globe and the shift towards networking these has produced another radical challenge for diplomacy. It has been dubbed by Professor of Journalism and Public Diplomacy at the University of Southern California, Philip Seib, “real-time diplomacy.”

Every communications revolution has challenged governments and foreign ministries by constricting their decision making time-frames. Seib tracks a few examples that put the current reality into perspective.

On the morning of April 19, 1775, there was a faceoff between American militiamen and the British army at Lexington and Concord that marked the beginning of the American Revolution. However, it wasn’t until April 23 that news reached New York and April 28 that it reached Virginia (Seib, p. 73). Today, these events could be live tweeted globally.

Or more recently, when CBS filmed the East German closure of the border between East and West Berlin on Sunday August 13, 1961, it wasn’t until Tuesday evening in the United States that the story was finally broadcast on television (Seib, p. 68).

Every advance that has reduced the time required for information to travel between two points has put pressure on decision time-frames for diplomats, whether the advance be the steam ship, train, telegraph, telephone, radio, television, or the internet.

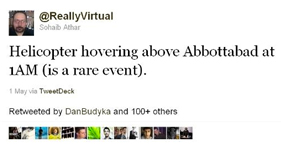

The point has now been reached where information not only travels instantly from almost anywhere on earth, it is also democratized. Information is unfiltered by traditional gatekeepers like newspaper, radio or television editors. Gone are the gentleman’s agreements between editors and officials to hold back or restrain sensitive reporting. These sorts of traditional approaches are now largely redundant when it’s possible for people like IT consultant Sohaib Athar to live tweet the raid that killed Osama bin Laden (see tweet). Even when major news organizations abide by these old standards of professionalism, they can be instantly rendered moot.

The point has now been reached where information not only travels instantly from almost anywhere on earth, it is also democratized. Information is unfiltered by traditional gatekeepers like newspaper, radio or television editors. Gone are the gentleman’s agreements between editors and officials to hold back or restrain sensitive reporting. These sorts of traditional approaches are now largely redundant when it’s possible for people like IT consultant Sohaib Athar to live tweet the raid that killed Osama bin Laden (see tweet). Even when major news organizations abide by these old standards of professionalism, they can be instantly rendered moot.

When it decided to report on the State Department’s WikiLeaks cables, the New York Times issued a note to readers that said in part:

After its own redactions, The Times sent Obama administration officials the cables it planned to post and invited them to challenge publication of any information that, in the official view, would harm the national interest. After reviewing the cables, the officials—while making clear they condemn the publication of secret material—suggested additional redactions. The Times agreed to some, but not all. …In all, The Times plans to post on its Web site the text of about 100 cables—some edited, some in full—that illuminate aspects of American foreign policy.

However, less than a year later the entire un-redacted stock of a quarter of a million cables was released online when Guardian journalist David Leigh published the passphrase to the master file in a book, while various websites further enhanced the cables’ accessibility by making them easily searchable.

Notwithstanding these technological developments, some of this change seems much more dramatic than it really is. The fact it used to take days or months for information to reach policymakers did not mean policymakers had all this time available to formulate policy and make decisions. Unless policy-makers were actually conveying the information themselves to headquarters, this travel time was dead time, and upon receiving the information, policymakers would still be under pressure to respond in a timely way. Improvements in internal communications also allowed policymakers to effectively buy time by making processing and transmission more efficient (for example, by replacing written with typed letters and typed letters with emails).

It also remains true that for many (probably most) foreign policy issues, policymakers are still under no real public pressure to act expeditiously. The public has an extremely high tolerance for the negotiation of tax treaties, free-trade agreements, reciprocal healthcare arrangements and the like. Policymakers have even been able to drag out global negotiations for years on issues as pressing and potentially catastrophic as climate change.

It is only in a limited number of high-profile issues that decision making timeframes have been dramatically curtailed. When your secret raid inside the territory of a foreign country is being live tweeted, there is not much time for your public position to be explained. But even in the instance of the Osama bin Laden raid, its pre-planned nature meant public lines could have been thought through in advance.

That said, unpredictable developments in high profile areas can force policymaking into uncomfortably tight timeframes. The revolution in Egypt was a case in point.

The uprising began on January 25, 2011, and by February 11, Mubarak had stepped down. U.S. policy needed to scramble in a highly fluid and uncertain environment that was taking place against the backdrop of a successful overthrow of the regime in Tunisia and a torrent of social and other media reporting and commentary on the unfolding events.

Not surprisingly, and reasonably, U.S. policy was initially unable to keep pace with developments. As social media and the traditional media erupted in a frenzy of support for the Egyptian protestors, the President and State Department were unable to instantly jettison a long-term partner and policy approach from day one.

On January 27, Vice President Joe Biden said the following in an interview with Jim Lehrer:

Jim Lehrer: Has the time come for President Mubarak of Egypt to go, to stand aside?

Joe Biden: No, I think the time has come for President Mubarak to begin to move in the direction that — to be more responsive to some of the needs of the people out there.

…

Jim Lehrer: Some people are suggesting that we may be seeing the beginning of a kind of domino effect, similar to what happened after the Cold War in Eastern Europe. Poland came first, then Hungary, East Germany.

We have got Tunisia, as you say, maybe Egypt, who knows. Do you smell the same thing coming?

Joe Biden: No, I don’t.

By January 30, the Obama administration line had evolved and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton went on the Sunday talk-show circuit, calling for “an orderly transition” and stating that the United States was “ready to help with the kind of transition that will lead to greater political and economic freedom.”

And on February 1, just a week after the protests erupted, President Obama announced that he had phoned President Mubarak and made clear “orderly transition must be meaningful, it must be peaceful and it must begin now.”

In comparison to some previous leadership transitions the United States has had to deal with—such as Reagan with Ferdinand Marcos and Bill Clinton with Suharto—this was policymaking at warp speed.

This might have been an extraordinary policy pivot in an incredibly short time frame that landed the United States on the right side of history, but it was still nowhere near fast enough to appease public expectations of a virtually instantaneous reaction. In the lead-up to this policy evolution, social media was overflowing with demands for the United States to make its policy position clear (and tell Mubarak to go). While it is hard to imagine the United States being able to responsibly shift any faster than it did, given the fluidity of events and the stakes, even this slight delay probably dented the United States’ wider reputation in the region as a champion of democracy.

In this super-saturated information environment, circumstances will emerge where it is simply impossible for foreign ministries to keep pace with events. It would be reckless for states to jettison deliberation and time to see how events unfold in favor of snap decisions that play to the crowd. At the same time, this environment now demands that officials communicate their positions (even holding positions) and technology provides them with the ability to defend their stance and mitigate negative fallout.

Rapid Brand Damage

A related challenge that connection technologies have created for foreign policy practitioners is the potential for nations to experience rapid, brand-damaging incidents. A factor feeding this trend seems to be that journalists in many countries now use social media as a source for breaking news and as a means of gauging public reaction to events.

Events that in the past might have gone unnoticed beyond a small community now have the potential to explode internationally, causing massive economic losses and even death.

In 2009, Australia experienced this new reality. A series of attacks on Indian students studying in Australia created a perception that the attacks were racially motivated. Australian police did not collect data along racial lines, so it was at first difficult to determine if the attacks were racially motivated or just an unfortunate coincidence. The attacks received some attention on social media in India and various Australian-oriented Facebook pages appeared promoting hateful messages about Indians.

Even with this social media element, the mainstream media quickly became the major actors in this crisis, fuelling a string of protests over the attacks in both India and Australia. Various factors inflamed the crisis. The notoriously vociferous Indian media on several occasions omitted critical facts, such as when Jaspreet Singh claimed that he was set on fire by unknown assailants but police alleged he accidentally burned himself while setting his car alight to make an insurance claim. The Victorian government also handled the crisis poorly.

The overall impact was damaging to Australia’s national brand-damaging. Australia’s third-largest export is education and its second-largest source country of international students at the time was India. Within months, student numbers had fallen dramatically, with government figures released in early 2010 revealing the number of Indians applying for student visas to Australia had fallen nearly 50 percent. Private government-purchased polling seen by the author also revealed Indian public opinion towards Australia had plummeted dramatically in key areas.

The Australian federal government responded in the same way many governments might. In June 2009, it ordered the National Security Adviser to lead a taskforce examining the attacks. But it was not until early 2010 that it had mobilized a comprehensive national response and by then the damage had been done.

This is the sort of crisis that fits Philip Seib’s concept of real-time diplomacy. It was generating outrage in one of Australia’s largest and fastest-growing export markets and causing serious economic and political damage. It required urgent action for which governments and foreign ministries at present are, mostly, wholly unprepared.

When a similar event happened in April 2012, in which a Chinese student was assaulted on a train, Australia responded differently. The student posted a message about the attack on the Chinese social media platform Weibo immediately following the incident, which was quickly reposted more than 10,000 times. This time former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd (who is fluent in Mandarin) reacted quickly, posting a response on Weibo himself, letting the student know he was going to ‘approach the police and department of education’ on his behalf.

In other instances, the inflammatory use of connection technologies has resulted in deaths. On July 12, 2010, Terry Jones, a radical clergyman form Florida, wrote a series of tweets attacking Islam, one of which read: “9/11/2010 Int Burn a Koran Day.” He followed that up with a Facebook group soliciting people to join his burn a Koran day. By September, Al Jazeera reported: “A Facebook page in support of the burning had more than 16,000 fans by Friday and was on the increase, while fans of opponents’ pages numbered in the hundreds of thousands.”

The Washington Post tracked the spread of the story from Twitter to mainstream media, including State’s monitoring of the issue:

On July 23, Jones was tweeting about having more than 700 Facebook friends for his International Burn a Koran group. Next, he did a short interview on CNN, and after that, on July 30, the National Association of Evangelicals, one of the largest collections of such churches, denounced the event and urged Jones to call it off.

Still, the stunt caused little commotion domestically, even as senior officials within the FBI, the State Department and U.S. military intelligence watched warily for the news to inflame sentiment in the Middle East and Asia.

“This is not the first time something like this has happened,” State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley said Friday. Other pastors had burned Korans before and posted video on YouTube. “But what is different is the potential that the world will be watching and reacting,” because of the contentious debate over the proposed Islamic center at Ground Zero.

Another lens this controversy was being analysed through was the response to the publication of cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad in a Danish newspaper in 2005.

Indeed the story spread and the consequences on the ground were very real. As the New York Times reported the fallout from one of the protests the reverend’s actions sparked:

Stirred up by three angry mullahs who urged them to avenge the burning of a Koran at a Florida church, thousands of protesters on Friday overran the compound of the United Nations in this northern Afghan city, killing at least 12 people, Afghan and United Nations officials said.

The dead included at least seven United Nations workers—four Nepalese guards and three Europeans from Romania, Sweden and Norway—according to United Nations officials in New York.

In other cases, these events can seem fleeting, doing limited brand damage. However, when there is the perception of a pattern (as with the attacks on Indian students or, say, U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan), there is cumulative damage that can have a major impact.

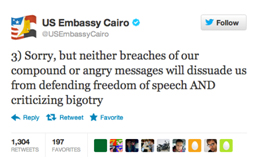

For democracies like the United States, responding to some of these crises can be challenging, especially when they involve fundamental freedoms. When an amateur video attacking Islam was posted online and began to attract attention in September 2012, the U.S. Embassy in Cairo issued the following statement on its website in an apparent effort to defuse escalating tensions:

The United States Embassy in Cairo condemns the continuing efforts by misguided individuals to hurt the religious feelings of Muslims—as we condemn efforts to offend believers of all religions.

Parts of the statement were also tweeted. When protestors subsequently breached the Embassy compound in Cairo (later, in Libya, four U.S. officials were killed in clashes, including the Ambassador), the embassy in Egypt modified its message tweeting:

Reflecting just how difficult it can be to manage communications in such a time-pressed and tense security situation, Politico later reported an administration official disowning the initial Embassy Cairo statement: “The statement by Embassy Cairo was not cleared by Washington and does not reflect the views of the United States government.”

Because information now has the potential to spread so rapidly, the facts are often ambiguous and can be out of direct government control, the response needed by governments is not fact-finding (although that is important in the medium term) but crisis public relations. And it is government-led public relations campaigns that need to account for the changes in the way people are communicating and the power of networks.

eDiplomacy Applied to Public Diplomacy

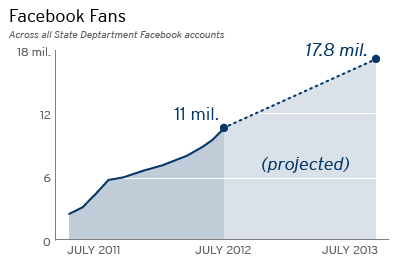

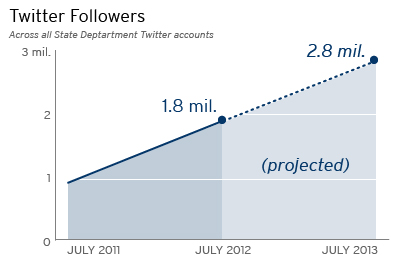

At State, ediplomacy’s use in public diplomacy is baked in. At the end of January 2012, State’s social media reach via Facebook and Twitter was over eight million people. That was already a larger direct reach than the daily subscriber base of the ten largest newspapers in the United States combined (although that is not to suggest influence levels or readership equated). By early August, it had nearly doubled, approaching 15 million.

There is quite a bit of nuance to these big-picture numbers. Foremost is the fact that, like any mass medium, not everyone is receiving your message, and in the case of social media probably only a very small proportion. Facebook is currently the dominant mass reach tool (see table) with around 13 million fans across nearly 300 pages. Even though State’s YouTube channels have had more than 16 million views overall, these are one-off views, whereas Facebook and Twitter offer the potential for reaching people on a daily basis.

Facebook, Twitter and YouTube Accounts Operated by the State Department

| Platform | Number | Total direct reach (August 9, 2012) |

| 288 pages | 12,862,585 fans | |

| 196 accounts | 1,883,344 followers | |

| YouTube | 125 channels | 16,337,350 video views with 26,900 channel subscribers |

State’s 13 million Facebook fans are also concentrated in four accounts run by the Bureau of International Information Programs (IIP). These are Global Conversations: Our Planet (now also in Spanish and the first foreign ministry site to pass two million fans), eJournal USA, Democracy Challenge and Innovation Generation (formerly known as Co.Nx). Global Conversations focuses on environmental issues, eJournal USA all things America, Democracy Challenge on democratic-related matters and Innovation Generation on entrepreneurship.

Together these four sites account for a little under eight million of these 13 million Facebook fans—with 49 percent of the audience under 24 years of age. The top ten countries where fans come from are generally non-English speaking (meaning content is pitched at a basic level of English literacy).

It is noteworthy, however, that the rapid growth in State’s social media audience has not been limited to these four well-resourced platforms. While from January 31, 2012 to June 12, 2012, IIP’s four Facebook sites grew their audience by 37 percent, all other State Department Facebook and Twitter platforms grew by 39 percent over the same period. Part of this growth in other sites is explained by a campaign IIP ran, which aimed to help 20 U.S. missions increase their social media audience by 100 per cent in nine months (February-September), with most posts hitting this target.

There are also several other large Facebook and Twitter feeds (see tables below), although eight of the 15 largest Facebook pages and four of the 15 largest Twitter feeds are operated out of Washington (see charts showing all sites by region and top 15 tables).

| Top 15 State Department Facebook Pages by Fans (as of August 9, 2012) | ||

| Administrative Location | Name | Fans |

| Washington D.C. | Global conversations: our planet | 2,004,503 |

| Washington D.C. | Democracy Challenge | 1,934,249 |

| Washington D.C. | Innovation Generation | 1,895,951 |

| Washington D.C. | eJournal USA | 1,889,189 |

| Jakarta, Indonesia | U.S. Embassy Jakarta | 507,057 |

| Islamabad, Pakistan | U.S. Embassy Pakistan | 455,513 |

| Cairo, Egypt | U.S. Embassy Cairo | 328,511 |

| Washington D.C. | Vision of America | 252,448 |

| Dhaka, Bangladesh | U.S. Embassy Dhaka | 226,417 |

| Washington D.C. | Iniciativa Emprende | 217,613 |

| Washington D.C. | U.S. Department of State | 147,576 |

| Lahore, Pakistan | U.S. Consulate General Lahore | 129,431 |

| Washington D.C. | America.gov (Russian) | 124,243 |

| Buenos Aires, Argentina | Embajada de Estados Unidos en Argentina | 101,417 |

| Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic | Embajada USA, Santo Domingo | 100,934 |

| Top 15 State Department Twitter Accounts by Followers (as of August 9, 2012) | ||

| Administrative Location | Twitter Account | Followers |

| Washington D.C., United States | Alec Ross | 376,365 |

| Washington D.C., United States | State Department | 312,317 |

| Washington D.C., United States | Travel – State Dept | 240,013 |

| New York City, United States | Ambassador Rice | 172,291 |

| Tokyo, Japan | Ambassador Roos | 54,349 |

| Jakarta, Indonesia | U.S. Embassy Jakarta | 53,022 |

| Beijing, China | U.S. Embassy Beijing | 48,202 |

| Bangkok, Thailand | U.S. Embassy Bangkok | 42,544 |

| Bogota, Colombia | U.S. Embassy Bogota | 36,175 |

| Jakarta, Indonesia | @america | 34,175 |

| Bangkok, Thailand | Ambassador Kristie Kenney | 32,727 |

| Washington DC, United States | USA bilAraby | 31,289 |

| Moscow, Russia | Michael McFaul | 31,049 |

| Caracas, Venezuela | U.S. Embassy Caracas | 24,410 |

| Manila, Philippines | U.S. Embassy Manila | 27,689 |

It is also worth noting that these figures exclude other social and digital means of engagement that U.S. embassies are using. Pictured (left) is the bottom of the email signature block used by the U.S. Embassy in New Zealand, which offers a host of ways to engage. The Department maintains a list containing many of these official accounts on its official Facebook site. Moreover, missions like the U.S. Embassy in China have had considerable success using Chinese social media platforms (with over 500,000 Weibo followers and 600,000 QQ followers).

It is also worth noting that these figures exclude other social and digital means of engagement that U.S. embassies are using. Pictured (left) is the bottom of the email signature block used by the U.S. Embassy in New Zealand, which offers a host of ways to engage. The Department maintains a list containing many of these official accounts on its official Facebook site. Moreover, missions like the U.S. Embassy in China have had considerable success using Chinese social media platforms (with over 500,000 Weibo followers and 600,000 QQ followers).

Although the scope of this study does not include an exhaustive analysis of State’s social media platforms, it is clear that social media is being used for a range of different purposes across the Department. Several broad categories are sketched out below.

1) Official messaging

The Bureau of Public Affairs manages eleven official Twitter language feeds as well as the official State Department Facebook page, YouTube channel, blog, Flickr account, Google+ page and Tumblr.

The messages from Public Affairs aim to be the official line and to deal with breaking news. Enormous care is put into ensuring messages accord with official U.S. government policy. As well as informing the American public, it also serves to inform and service foreign journalists and operates 10 non-English Twitter feeds (in Arabic, Chinese, Farsi, French, Hindi, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Turkish and Urdu).

This internationally-facing aspect of its work has a public diplomacy component. As Deputy Assistant Secretary of Public Affairs for Digital Strategy Victoria Esser put it in January 2012, after the launch of State’s official Turkish twitter feed:

Our Ambassador to Turkey Francis J. Ricciardone, Jr. explained the rationale—the U.S. relationship with Turkey is a high priority, and we are always seeking to expand the ways in which we can inform and engage with the people of Turkey. Social media offered us a way to do that in real time with much broader reach than we could ever hope for with traditional shoe leather public diplomacy.

As a vehicle for providing the world with quick, official lines from the State Department, social media is excellently suited. It allows State to clarify or push out official lines without the need to organize and host a press conference, as well as to broadcast a wide range of relatively minor events and messages. It can also prevent escalation of false stories, such as when it was claimed Madagascar’s ousted president had sought refuge inside the U.S. Embassy in Antananarivo. The range of platforms managed by Public Affairs also provides considerable flexibility in the way State can respond; for example, in a sentence or two on Twitter, by a video statement on YouTube, or more informally on the blog.

Although Public Affairs’ social media sites do not reach an enormous audience, its reach, to date, is not insubstantial (its official English Twitter feed has over 300,000 follows, its Facebook page about 150,000). And while this report did not include an analysis of the followers, it is likely they include a host of important influencers from around the world, who provide State (through their social media connections) with far ranging reach. In this way, it is not always possible to assess the impact of social media platforms by the quantity of followers alone.

2) Official messaging-public diplomacy hybrid

Social media accounts run by U.S. embassies and consulates vary in style (as one official running an embassy site put it “we are all still learning”), but they tend to sit somewhere on a spectrum between communicating and engaging with influencers (such as journalists and officials) and the interested general public (often in the relevant local language).

Although they are meant to focus on promoting the Mission Strategic Resource Plan (MSRP), a February 2011 Office of Inspector General Review of the use of social media by the Department of State found (p. 5):

With regard to site content, public diplomacy staff members are engaging in a balancing act. They know they are supposed to focus on the MSRP, but they fear that too great an emphasis on serious issues will make the site heavy, boring, and unable to attract an audience. Some have developed lighter, more creative content, reasoning that if their MSRP goal is to reach a younger audience, anything they do to achieve this automatically falls under the MSRP.

Collectively, these platforms reach a large audience, with the single largest embassy account, the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta’s Facebook page, which has over half a million fans and is written in Bahasa squarely aimed at the Indonesian public.

3) Consular affairs

Social media is also playing an increasingly important role in consular affairs. It is being used to provide foreign publics with U.S. visa information, to provide travel information to U.S. citizens travelling abroad and to coordinate in disaster response situations. Examples include the Consular Affairs Facebook page and @TravelGov Twitter feed.

This is among the most important topics for many embassies on social media. It draws in big audiences and has a cost saving objective by getting people prepared before they visit a visa officer. In general, however, consular issues are yet to generate the same level of innovative flair State has exhibited elsewhere.

4) Diplo-media

State’s rapidly growing social media audience is at least in part the result of a move into “diplo-media.” This new category of media appears to have three core qualities:

• Content that seeks to advance broad national interests.

• An editorial approach that downplays associations with the State Department or U.S. government.

• Content that is participatory and towards the entertainment end of the content spectrum.

So what type of content do these sites promote and how does it seek to engage in an entertaining way? Below are two examples from a single day in June. First, is the 50 States in 50 days campaign that ran across several of the Facebook pages. It was created to support President Obama’s national travel and tourism initiative and developed in partnership with the economic bureau and BrandUSA. The feature on Alabama (pictured) seems designed with two messages: highlighting U.S. diversity and tourism (entertainment options—NASCAR and beaches—and historical linkages—the Civil Rights Trail). The post then linked to the Alabama page of the DiscoverAmerica.com website.

So what type of content do these sites promote and how does it seek to engage in an entertaining way? Below are two examples from a single day in June. First, is the 50 States in 50 days campaign that ran across several of the Facebook pages. It was created to support President Obama’s national travel and tourism initiative and developed in partnership with the economic bureau and BrandUSA. The feature on Alabama (pictured) seems designed with two messages: highlighting U.S. diversity and tourism (entertainment options—NASCAR and beaches—and historical linkages—the Civil Rights Trail). The post then linked to the Alabama page of the DiscoverAmerica.com website.

Second, Innovation Generation had a post of three women (two wearing the hijab) that asked: “Entrepreneur Spotlight: How did three women from Egypt turn pregnancy advice into a thriving online business?” with a link to a BBC article, the question to followers being a characteristic trait of the postings across the four IIP Facebook pages. The BBC article describes how an Egyptian woman came up with the idea for SuperMama: a website described as “offering tips and expert advice for mothers and mothers-to-be, the first of its kind in the Arab world.” Besides promoting the underlying message of positive U.S. engagement with the Arab world, the BBC article also offers a plug for U.S. innovation:

Second, Innovation Generation had a post of three women (two wearing the hijab) that asked: “Entrepreneur Spotlight: How did three women from Egypt turn pregnancy advice into a thriving online business?” with a link to a BBC article, the question to followers being a characteristic trait of the postings across the four IIP Facebook pages. The BBC article describes how an Egyptian woman came up with the idea for SuperMama: a website described as “offering tips and expert advice for mothers and mothers-to-be, the first of its kind in the Arab world.” Besides promoting the underlying message of positive U.S. engagement with the Arab world, the BBC article also offers a plug for U.S. innovation:

Setting up the site was a big risk for Yasmine…Help came in the form of the MIT Arab Enterprise Forum Business Plan Competition, where entrepreneurs from across the Arab world pitch their business ideas. Out of 3,800 applicants, SuperMama was one of the 30 semi-finalists. Yasmine picked up invaluable contacts in the IT industry who helped develop the business model and pointed out its weaknesses.

The distancing from the U.S. government or the State Department is best displayed by two of the Department’s largest Facebook pages: Democracy Challenge and Innovation Generation. Until recently, neither site mentioned it was run by the State Department on its opening page. State officials noted this was an omission (and it has since been changed). While the vast bulk of State’s sites do point to their official status (for example the many embassy Facebook pages and Twitter feeds), there is a tendency on even these sites to avoid traditional diplomatic bureaucratese and adopt a less obviously governmental style.

A hybrid version of diplo-media involves the repackaging of State Department materials (such as speeches) into shorter, more entertaining formats. A good example is the below music video mashup of Clinton’s LGBT speech.

5) Network extension and retention

An emerging use for social media at State is in the area of network extension. Part of a diplomatic mission’s role is to organize an endless round of visits. Visitors are frequently trotted out to all the usual suspects, and there is very limited incentive on the part of time-pressed diplomats to broaden these networks and be expeditionary.

Social media is being used to change this. Some senior diplomats at State make a point of highlighting their twitter handle or Facebook page every time they speak at an event. Diplomats like Alec Ross get between 10 and 20 percent of the entire audience signing up after each event. The theory is that these ever expanding networks can be harnessed for ideas when you need to find a new contact or expert, and allow for sampling of a wider audience than just the elite VIP networks embassies traditionally maintain. They allow diplomats to maintain a very loose association with contacts via their updates over an extended period and make it more likely they will show up at a future repeat engagement.

6) Resiliency capability

At a big picture level, State’s widespread adoption of social media has given it a new resiliency capability. As discussed above, the rapid spread of social media around the world has increased all countries’ exposure to nation brand-damaging events. A single event that might previously have been reported in only limited circles can now explode into a media firestorm that can have real costs in lives, standing and money.

To some extent, it is impossible (and contrary to Western principles) to try to prevent this communication taking place. However, it is still the job of the foreign ministry to do its best to protect the national interest of the country and people they represent. In a world where these messages are travelling via social media and these tools are readily accessible to foreign ministries, development of a sound public relations strategy that includes a social media response can mitigate the worst impacts.

State has the makings of this sort of resiliency capability, although it is not yet necessarily conceived of in this way. This capability has three components:

a) Real-time monitoring: The Bureau of Public Affairs’ Rapid Response Unit has a small team monitoring social media responses to developments that have the potential to impact U.S. national interests. They produce short daily briefing reports with an anecdotal look at the online response to specific events/issues (for example, on the closure of the U.S. embassy in Syria) across the Arabic, Chinese, English and Spanish social media spheres.

b) Identification and cultivation of key online influencers: It is now possible to create maps of online influencers by subject area, which would allow diplomats on the ground to have a better sense of who is driving discussion on specific issues and who they should be reaching out to (in the same way diplomats currently use intuition to identify and build relations with politicians, officials and journalists they think influential). The Office of Audience Research in IIP is exploring analytics and social media management tools as a way of helping to better understand online conversations and the impact State is having, but could usefully focus on identifying influencers.

c) Capability to speak (and engage) directly with a mass audience: State now has a global reach approaching 15 million people on Facebook and Twitter alone and that reach remains on a very strong growth trajectory.

Combined, these three facets amount to a nascent resiliency capability that would allow State to quickly identify social media conversations that have the potential to affect national interests, to put their own case directly to a large online audience, and to reach out and explain their perspective to key online influencers.

Foreign ministries new to social media often struggle to look beyond its broadcasting function. Asked in July 2012 whether he shared Secretary Clinton’s view that technology needed to be integrated into diplomacy, Australia’s Foreign Minister Bob Carr gave a telling reply: “I’d like to see that done, but—I might be old fashioned—I think that the substance is more important than the means of delivery.”

The above discussion suggests that substance has to factor in social media. When an obscure reverend’s tweets can lead to global protests and the best means of reaching people in a consular crisis is via social media, the substantive work of a foreign ministry needs to adapt. Social media is being used at State for broadcasting, but also for listening, engaging, organizing and for crisis public relations.

Options for Social Media

Social media is changing diplomacy in several ways. It is bringing new actors into the foreign policy-making mix (both prominent individuals and organizations such as Invisible Children). It is allowing foreign ministries to listen to the concerns and interests of local populations in a far more cost-effective way than opinion polling. It is also allowing foreign ministries to communicate directly with mass audiences, including those increasingly hard to reach via traditional media (13 million directly via Facebook alone and about half of these under 24 years of age) in a more personal, immediate and ongoing way than traditional media allowed.

The State Department has been at the vanguard of the shift to social media and as such is the first foreign ministry to come up against some hard decisions these technologies throw up. Unfortunately, none of these issues were dealt with in the Office of Inspector General February 2011 Review of the use of social media by the Department of State.

One of the biggest questions State is now facing is its status as a de facto media empire. State now communicates directly with a massive global audience that is growing at an extraordinary rate. Officials at State have two theories about where this could lead. First, audience reach could start to plateau out because of a technology change or as State saturates the finite audience interested in anything produced by the U.S. government. Or second, it could continue to expand its audience and content variety and as one official put it become a large niche media actor “like Sky” the British satellite broadcaster.

At this point, however, audience growth rates show no indication of slowing down.

Through its “diplo-media” social media presence in particular, State engages in a range of activity that directly resembles a major news organization. It advertises its platforms to build audience, it generates its own videos, pictures, graphics and written content. In addition, it has staff pushing out and updating content 24 hours a day.

This opens up a web of complex issues:

- Should State continue the trend towards the creation of content with broader audience appeal, particularly more entertainment style content? Programs like the Broadcasting Board of Governors’ (BBG) hugely popular OMGMeiyu, for example, which teaches Chinese people everyday American English (including uses for the words “booger” and “snot” (see below)) and is produced from popular star—Jessica Beinecke’s—kitchen table would be an easy fit for some of State’s social media platforms. Or Parazit, another popular BBG show. This sort of programming would sit well in the diplo-media category that suits younger audiences and could even be merged into existing embassy websites, where some, such as the U.S. Embassy in Syria, already have “Join our weekly ‘American Idiom’” free SMS alert programs (pictured).

- What level of oversight should this media empire have and who should decide its editorial line: bureaucrats? (At present, there are several layers of bureaucratic hierarchy and the Smith-Mundt Act which act as checks on political manipulation).

- What level of advertising expenditure is appropriate for a government-backed media empire (current State Department thinking is that this should be very minimal)?

- An emerging policy issue is the potential overlap between BBG and State-produced media as both shift towards online oriented content. Where should both organizations’ respective efforts be limited to?

These technologies have also brought to the forefront the old divide between public affairs and public diplomacy and the anachronistic Smith-Mundt Act. Historically, the Office of Public Affairs dealt with the press and reporters, while Public Diplomacy dealt with the general public overseas.

The Smith Mundt-Act (formally the United States Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948) as amended prohibits domestic access to information produced by Public Diplomacy that is intended for foreign audiences, perpetuating this division at State and creating a general firewall between Public Affairs and Public Diplomacy.

The nature of online communications and State’s development of a new media empire make this old distinction irrelevant. As one departmental official put it, “We have long thought that aspects of Smith-Mundt need to be modernized. However, the legislation still exists and we continue to abide by the letter and spirit of the law—we cannot use Public Diplomacy resources to create material for domestic distribution in the United States.” This produces absurd consequences like the fact that while the State.gov website and embassy sites are hosted on the same platform, because of Smith-Mundt they are managed and paid for separately, and public diplomacy materials are at least two clicks away from the State.gov website. There is now little doubt this Act needs major modernization (with proposals already made along these lines) or repeal.

Any U.S. citizen can access content produced by Public Diplomacy officials, and at least a proportion of State’s followers on social media intended for foreign audiences are in fact American citizens. As the OIG report on State’s use of social media found (p. 10):

There is nothing to prevent Americans from posting comments and questions on embassy social media sites, and 5 FAM 794 a. (6) (b) notes that, “[d]ue to the open and global nature of social media sites, department-generated public diplomacy content must be carefully reviewed to avoid violations of the United States Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948, as amended (Smith-Mundt).” About 10 percent of the embassy Facebook pages examined had a significant number of postings by Americans, and many more had some postings.

Communications from both Public Affairs and Public Diplomacy also often overlap. And the nature of the digital space means American citizens are themselves often involved in the dissemination of State’s messages abroad. For example, the content State creates for the Iranian public in Farsi is consumed on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, sites that have been hard to access in Iran (and which are getting even harder to access thanks to Iran’s attempt to develop a ‘halal’ domestic intranet). It is widely assumed this Farsi content is accessed by Iranian Americans who then repackage and deliver it into Iran via email, for example.

The merger of Public Affairs and Public Diplomacy would have the added benefit of creating a leadership with an overview of State’s sprawling media empire.

One risk of this centralization is that it will kill off innovation. While support for social media’s rapid and unstructured rise at State has come from the very top, there is an inevitable tendency among all bureaucracies to try and control. A traditional foreign ministry approach to social media based on rigid rules, hierarchies and constraints will kill off the success State has enjoyed so far. A look at other foreign ministries’ mostly dismal efforts in this space testifies to this. So the emphasis of any consolidation should be on maintaining flexibility and innovation. It would also have to consider how to forestall political manipulation of this media empire by Administration appointees.

That concludes an overview of ediplomacy’s integration into public diplomacy. The next section looks at its application to the new foreign policy issue of internet freedom.

| « Read Part 2: The History of eDiplomacy at State |

Read Part 4: Internet Freedom » |