New teachers are essential to K-12 education. They allow the system to grow as the number of students grows, and they replace teachers retiring or taking other jobs. In light of the size of the K-12 sector, it’s not surprising that preparing new teachers is big business. Currently more than 2,000 teacher preparation programs graduate more than 200,000 students a year, which generates billions of dollars in tuition and fees for higher education institutions.

Preparing new teachers also is a business that is rarely informed by research and evidence. In 2010, the National Research Council released its congressionally mandated review of research on teacher preparation. It reported that “there is little firm empirical evidence to support conclusions about the effectiveness of specific approaches to teacher preparation,” and, further on, “the evidence base supports conclusions about the characteristics it is valuable for teachers to have, but not conclusions about how teacher preparation programs can most effectively develop those characteristics.” That there is no evidence base about how best to prepare people to teach is concerning.

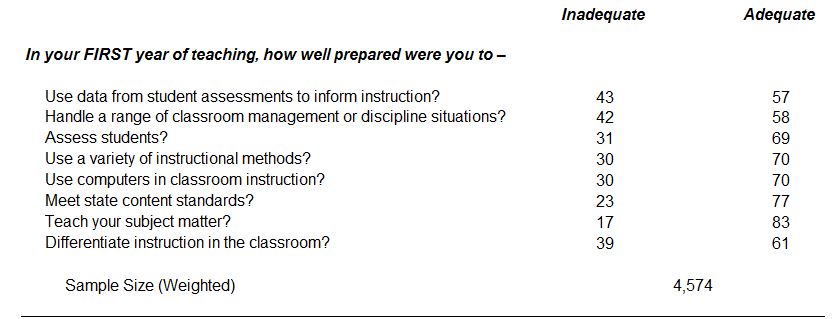

In 2012, the Schools and Staffing Survey conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics asked a nationally representative sample of new teachers about their preparation experiences. Specific questions asked how well new teachers thought their programs prepared them to manage classrooms and discipline students, use a variety of instructional methods, teach subject matter, use computers, assess students, differentiate students, meet state content standards, and use data from assessments to inform instruction. Teachers could say they were not at all, somewhat, well, or very well prepared. I combined teachers saying “not at all” and “somewhat” into one statistic, which I labeled “inadequate.” A “somewhat” category is vague, but I think teachers that selected it were indicating they perceived a gap in their preparation. I combined “well prepared” and “very well prepared” into “adequate.”

In six of the eight categories, 30 percent or more of new teachers felt their preparation was inadequate. More than 40 percent of teachers felt their preparation was inadequate for managing classrooms and for using data to inform instruction. Using data and managing classrooms are important parts of teaching. Imagine if 40 percent of new firefighters thought they were inadequately trained to use a hose. On the plus side, only 17 percent of teachers felt their preparation was inadequate to teach their subject matter.

Because teachers named the program from which they graduated, we also can look at how teachers rated adequacy in different programs. SASS had 23 programs that contributed 15 or more new teachers[1] to its sample. (Confidentiality restrictions preclude naming them here.) The lowest-rated program averaged a rating of 53 percent “inadequate” for the eight dimensions. (The median teacher from that program thought their preparation was inadequate.) The highest-rated program averaged 16 percent “inadequate” for the eight dimensions. Even looking at this small set of programs (compared to the 2,000 existing programs), this four-fold variability suggests there are strong and weak programs. Statistical analyses using data from Washington state and Missouri also shows that programs vary in the effectiveness of their teacher graduates.

Adequacy of teacher preparation from perspective of new teachers*

Source: 2012 Schools and Staffing Survey. “Inadequate” is the sum of “not at all prepared” and “somewhat prepared.” “Adequate” is “well prepared” and “very well prepared.” Responses are weighted by teacher sampling weight.

*New teachers as defined by those with four years or less of teaching experience. Nine percent of this sample had at least some teaching experience before 2008 and skipped these questions.

Accumulating a research base to support stronger preparation programs would mean studying questions that arise in preparing new teachers, such as the right balance between theory and practice, how best to use data, and approaches for managing classrooms. It would be years before results from such efforts emerge. But one way for programs to improve in the near future would be to use data on how well their graduates perform in promoting student learning. For example, data might show that particular approaches for teaching reading are associated with higher reading scores. That information could be incorporated into program courses. Using scores to improve programs emphasizes that the outcome of teacher preparation programs is learning.

As commonsensical as it may seem, using test scores as outcomes creates sharp tensions within the education community. The tensions are illustrated by a recent federal effort. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Education set out to create regulations for teacher preparation programs supported through funding under the Higher Education Act. ED named eighteen individuals, from state governments, teacher preparation programs, and other organizations, to a “negotiated rulemaking” committee that was tasked with drafting the regulations.

The committee progressed through its agenda of meetings but ultimately hit a roadblock it could not surmount. Its members could not agree on the use of student test scores. With the collapse of negotiations, the task of drafting regulations fell back on the Department. It released its draft last week. The regulations call for programs to report test scores of the students of their graduates, along with other indicators such as employment rates of graduates.

Why all this back and forth about test scores? Letters written in 2012 to the committee from deans of preparation programs (here and here) give an indication why they thought the use of test scores was a bad idea. Ironically, the letters argue that using test scores was not supported by scientific evidence. In light of what the National Research Council reported, the deans appear unconcerned about being hoisted on their own petard. One letter wrote that “We need a great deal more research across the K-12 years and subjects that are taught to know what teachers do that leads to the best learning outcomes, and we need valid and reliable observation measures to assess this.” But if this is the case, what is the basis for their current programs? Shouldn’t they be preparing new teachers based on what teachers do that leads to the best learning outcomes?

There are known issues in using statistical models of test scores to measure how effective teachers are—for example, a teacher’s measured effectiveness may be volatile from year to year because it’s based on a small number of students. But averaging results for teachers in different schools and districts, which is what preparation programs would be doing, removes most of the issues. A program whose graduates rank low on these measures year after year is reasonably likely to be inadequate in preparing its students.

One letter did refer to using performance assessments, which are tests prospective teachers need to pass to be certified to teach, much like prospective lawyers must pass the bar or prospective doctors must pass medical boards. Performance assessments are a way to ensure graduates of preparation programs have learned what their programs wanted them to learn. But the U.S. Department of Education Secretary’s report on preparation programs pointed out that many states set low passing scores (“cutpoints”) for their performance assessments and nearly everyone passes. How useful could an assessment be if 96 percent of those taking it pass? The rate of failing the written drivers test is higher. And knowing how teachers really perform is better than knowing how they might perform.

Other voices, however, weighed in to support using test scores and other “real” performance information to assess preparation programs. A task force of the American Psychological Association issued a report that encouraged efforts to evaluate preparation programs using value-added scores, observations of classroom performance, and surveys of program graduates. The task force’s view was that decisions about the merits of a program should be made “based on evidence that is available now, rather than evidence we might like to have had, or that might be available in the future.” The task force did not want the perfect to be the enemy of the good. (ED’s draft regulations incorporate many of these proposals.) Similarly, the newly formed Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation recently adopted standards that emphasize outcomes. As of now, these views appear to be prevailing, though with so much flux there is always the possibility of backsliding.

Reporting outcome data can improve preparation programs in different ways. Programs can scrutinize the data to identify what’s working and what’s not, which might stimulate efforts to design new approaches. And even if preparation programs ignore outcome data, it might push programs to change if it is posted publicly, as the draft regulations currently call for. Prospective students then can react to it. Reporting that 53 percent of a program’s graduates were inadequately prepared would signal prospective students what they might experience too. And the data will show whether programs place students in teaching jobs.

The time has arrived for teacher preparation programs to use evidence and data. It is being pushed by government regulation, but that will take a while—the draft regulations call for full implementation by 2020. Programs can move more quickly if they want to, and let’s hope they do. Every year, those hundreds of thousands of new teachers enter real classrooms and teach millions of students. If new teachers are well prepared, it can only be good news for students and parents.

[1] “New teachers” are defined here as those with one to four years of teaching experience.

Acknowledgement: I want to thank Ellie Klein for her expert assistance in tabulating the SASS data.