Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

This policy briefing explores the impact of political, social, and economic marginalization on Jordan’s youth. It highlights the growing tensions between the government and its increasingly agitated young citizens over the matter. Those tensions manifest in political apathy, disaffection among tribal youth, and radicalization. If the issue of youth cohesion and inclusion is not tackled, further erosion of Jordan’s stability and security will take place. Policies aimed at addressing those issues should avoid approaches that reduce youth to a security threat. The agency of young people and their relationships to their communities must be at the core of government strategy, resource allocation, and implementation.

Key Recommendations

- Bolster government-led youth initiatives through strengthening the Ministry of Youth (MoY), including youth in both the development and implementation of initiatives, and establishing better coordination between government institutions, NGOs, and donors.

- Foster youth political inclusion through lowering the minimum age for candidacy in elections, introducing youth quotas in parliament and municipal councils, and accelerating youth voter awareness campaigns.

- Promote civic youth through developing and teaching curriculums that encourage civic engagement, allowing youth spaces for political and civic participation to flourish, and incorporating a “youth inclusion” principle in NGO and civil society registration procedures.

- Ease the school-to-work transition through developing employment training programs and enhancing vocational opportunities in secondary and tertiary level education in Jordan. Public-private and private sector initiatives should be encouraged to drive the process.

Introduction: Jordanian Youth Sitting at the Margins

One of the major features of the Arab uprisings that gripped the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in 2010 and 2011 was the role that young people played in mobilizing dissent and frustration. Young Jordanians joined their peers from across the region to call for political reform and protest poor life chances, but with little to show for their efforts.

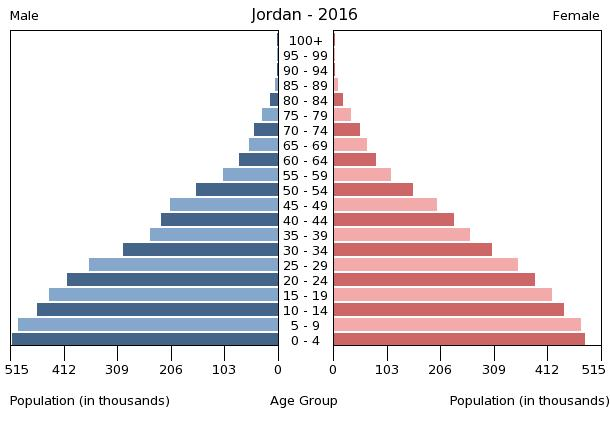

Figure I: Population Pyramid

Jordan, like other countries in MENA, has a young population. The United Nations (U.N.) estimates that more than 70 percent of the country’s 6.5 million citizens are under thirty. Youth make up 22 percent of the overall population.1 Despite their numbers, young Jordanians have been marginalized by the state and society. This policy briefing explores the layers of youth exclusion in Jordan, highlighting the political, social, and economic obstacles facing young Jordanians and particularly young women.2 It discusses the consequences of youth marginalization, which include apathy and distrust toward existing political institutions and leaders, the breakdown of the social compact between tribe and state, and radicalization. If the issue of youth cohesion and inclusion is not tackled, Jordan’s stability and security can seriously erode. However, in addressing those destabilizing factors, it is important to avoid approaches that reduce young people to a security risk. This briefing therefore urges the government, leaders, and international donors in Jordan to direct more resources to youth programs and policies that foster youth political inclusion, promote civic engagement, and support young people in their transition from school to work.

The layers of youth exclusion

Jordanian youth experience multiple layers of marginalization, intimately interconnected with socioeconomic, political, religious, national, sectarian, sexual, and gender dynamics. This is exacerbated by poor political, social, and economic prospects in the face of societal pressures to earn enough to establish independent homes, contribute to family finances, and marry.3 As detailed in this section, youth exclusion manifests in structural barriers to youth political participation, civic engagement, and access to economic opportunities imposed by both the state and society. Young women also face a number of additional barriers, especially when it comes to their experience of public spaces and social cohesion.

Closing the political doors to youth

The democracy deficit in Jordan is one compelling reason why its population joined the revolts of 2011-12.4 Jordan is not a democratic state, and foreign donors have expressed concerns that progress on fundamental rights to improve political freedoms are too slow.5 Barriers to political participation are higher on young people than other citizens. Jordanian authorities offer little by way of invitation to draw its young population into participation and civic life. Youth are marginal in learning and playing a role in Jordan’s deliberative and governing frameworks.

In fact, young Jordanians accuse authorities of actively stifling opportunities for inclusion.6 Public spaces are highly constricted places for youth because of the ways in which local governing authorities police and control them. Places like schools, college and university campuses, and other “social” spaces that should welcome youth participation and activism are constrained. Despite this, student activism in Jordan has persisted. Students have formed local networks to address their concerns, as well as wider socioeconomic and political issues. They have explored various political avenues, including protests against government-imposed price hikes and politically sensitive issues such as normalization with Israel.7

Such activism, however, comes with a high price tag. Students are constantly monitored. Student protests against issues such as fee hikes have led to suspensions and expulsions.8 Security forces have also targeted leaders and organizers in groups such as the National Campaign for the Rights of Students, also known as “Thabahtona,” amid claims that their role undermines and threatens university and governance norms.9 “They see us as the enemies of the state not the active citizens of our future society,” said one such student leader.10

Even in terms of the supposedly innocuous music scene, many, including hip-hop and rap artists, dancers, MCs, and producers, decry the levels of control by governing authority. “I was called in by the ‘mukhabarat’ and they wanted all of my lyrics,” stated one local artist.11 Another claimed that restrictions on public space that stop young single men from gathering to perform, dance, or be part of an audience “suffocate us.”12

Additionally, structural obstacles to political participation and joining public office persist in excluding youth in Jordan. Lower-order decision-making bodies such as civil society organizations, community groups, and school and university student councils, where youth could gain experience and engage in activism and stake-holding, have long been subject to such severe forms of control as to render them redundant in this respect.13 One encouraging development was apparent in the decision by the Jordanian government to lower the minimum age for candidacy in local elections to 25 years in preparation for the August 2017 elections.14 However, the minimum age to run for parliament in Jordan is still 30 years and over a $700 deposit is required to stand.15 Such factors act as effective obstacles to youth inclusion.

Limits to civic engagement

The attitudes of governing authority reduce the agency of youth to a state of passive beneficiary. There is wide agreement among many analysts at the U.N., Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and other international organizations on youth issues in Jordan that state and state-assisted activities are limited in terms of programmatic approach.16 Jordan’s National Center for Human Rights also consistently reports that the state fails to encompass its youth in the civic life of the country.17 This means that youth participation in Jordanian civil society, including in roles on the boards of state-registered organizations, is, again, highly restricted.18 This has attendant consequences for the youth’s collective and individual sense of civic identity, stake-holding, and empowerment.

This situation is compounded by the absence of state-led capacity building in terms of education curricula, critical thinking, and preparation for civic engagement and active citizenship. The state and many donor actors have failed to move beyond the rhetoric of “civic education” to implement schemes that build capacity among young people in terms of volunteering or setting up their own organizations. Civic education initiatives are particularly absent outside cosmopolitan centers, like Amman. In towns like Zarqa, Maan, and Irbid,youth centers are poorly resourced and underutilized.

This highlights the complex layers of stratification experienced by young people, including the physical, tribal, indigenous, refugee, national, economic, and social barriers that contribute to the marginalization of various groups. Development assistance, whether governmental, non-governmental, national, or international can sometimes overlook such stratifications, collectively lumping Jordanian youth into a one-size-fits-all category that leads to the objectification and even securitization of young people. This is particularly relevant in programs on countering or preventing violent extremism (CVE/PVE). Additionally, the extent of intersectionality present among those various groups is rarely recognized.

Economic margins: The unemployment problem

The Jordanian economy has failed to expand to allow for the number of young Jordanians entering the work force on an annual basis. Youth unemployment is one of the most pressing issues facing Jordan. It was a significant factor in mobilizing youth in different forms of protest – from taking to the street to using bank notes to highlight their claims.19 In 2017, the World Bank estimated that youth unemployment stood at 36 percent.20

Structural adjustment advocates and neo-liberal advisors have increasingly urged the state to also look to Jordan’s private sector to help find solutions to this challenge. The growing cooperation between the state and private sector is apparent in the award of contracts to the private sector. For example, the Ministry of Education awarded a contract to a private provider, Luminus, to establish initiatives to cultivate entrepreneurial growth among young people.21 Similarly, a government initiative with private providers for youth technical and vocational training (TVT) is set to admit 6,000 students to TVT centers by 2018-19 to help tackle the youth unemployment crisis.22

However, the necessary economic “ecosystem” for youth employment coupled with entrepreneurial activity in Jordan continues to be absent. The prevailing cultures of corruption, nepotism, and “wasta” – broadly defined as being reliant on networks of influence through family, friends, and other social groups to access power – stunt youth employability. Youth in Jordan perceive wasta as a major constraint on their chances of finding work, as many lack the social capital that lies at the foundation of the practice. It undermines their ability to compete in the job market.23 In a 2013 Gallup poll, 85 percent of Jordanian youth agreed with the statement that, “knowing people in high positions is critical to getting a job.”24 Similarly, a wider environment of legislation, regulations, and banking norms that inhibit start-up cultures, particularly for young people, inherently reduces the effectiveness of a myriad of entrepreneurship programs in Jordan.25

These deep-seated structural challenges lead one to question whether the private sector has the ability and incentive to effectively fill the space of the state and take on the governmental burden of reducing youth unemployment. However, state initiatives have fallen short. Ministry of Labor initiatives – supported by a variety of local and donor actors – on youth employment are often ad-hoc, lack programmatic approaches, and do not consistently link up with approaches developed by the Ministry of Youth.

The link between state and private sector economic initiatives on youth employment is still not as successful as it should be. The non-governmental sector in Jordan, including civil society organizations like Injaz, have also been supporting the government in the development of initiatives that build skills and cultivate entrepreneurship among youth in Jordan. Coordinating, monitoring, and enhanced donor conditionality can better serve youth employment issues.

Double burden: Young women

Systemic social, political, and economic practices have marginalized young Jordanian women. Despite some noted improvements in opportunities for political participation, state and society continue to constrain and limit the potential of Jordan’s young women even more so than their male counterparts.26 Gains in development such as ending the gender imbalance in education for young Jordanian women have yet to transform into advances in social, economic, and political participation.27

The gendered dimension to the issue of marginalization leaves young women virtually invisible from the public debate beyond symbol or token. For example, although female quota provisions to increase political participation for female candidates in Jordanian parliamentary (15 quota seats) and municipal (25% of all seats) elections are welcomed, they still structurally deny young women because of age restrictions on candidacy.28 Institutionalized patriarchy along with the resilience and reification of tribal networks further excludes young women and reinforces social attitudes that tend to either inhibit or banish them from the public space. In turn, this undermines opportunities for social cohesion.

Female participation in the Jordanian labor force is low. Jordanian government statistics indicate that only 13.2 percent of Jordanian women (including young women) are economically active (employed or seeking work).29 Moreover, young Jordanian women are experiencing high rates of unemployment, especially compared to their male counterparts (see below). 30 Yet barriers such as education are not the problem. Jordanian women have high literacy and college graduation rates.

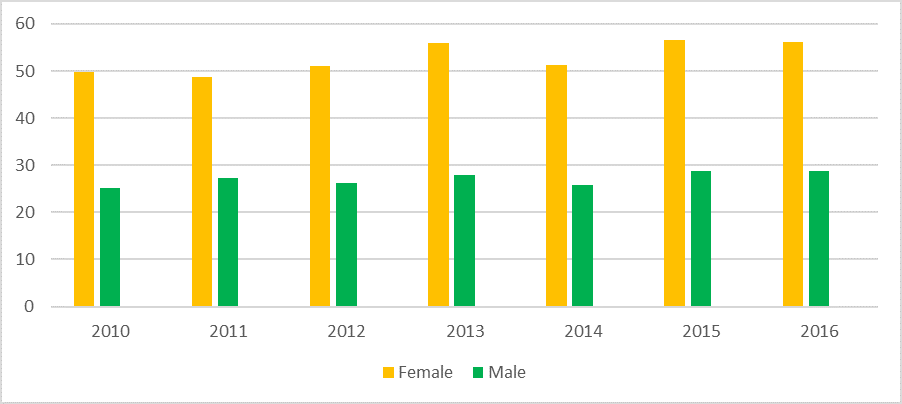

Figure II: Female/Male Youth Unemployment (15-24 years old)

Job creation for young women is a pressing challenge. Low wages, lack of childcare provision, poor public transport infrastructure, along with cultural and societal constraints are among a plethora of checks that discourage or stop young women from achieving their economic potential and contributing to the Jordanian economy.31 Moreover, even once in the workforce, young women experience pay gaps, earning 41 percent less than men in the private sector and 28 percent less in the public sector.32

Donor organizations, international NGOs, and members of the Hashemite royal family have promoted women’s rights, gender justice, and issues of equality with some successes such as the above-mentioned female quotas for national and municipal elections. Nevertheless, the persistence of structural barriers affects young women more than men, particularly in terms of their underrepresentation and the muting of their voice in fora of power.

The consequences of youth exclusion

Due to the limits to political, civic, and economic engagement described above, youth have become distrustful of political and public life in the country. As participatory processes have narrowed and left young people marginalized, the distance between the state and citizen has expanded. The state is becoming increasingly vulnerable as it loses the support of important constituencies, such as the tribal youth, which are challenging the long-held social compact between tribe and state due to continued exclusion. The aforementioned layers of political, social, and economic marginalization have also been important factors in youth radicalization.

Youth apathy to political and public life

Even though Jordanian youth have the right to vote at the age of 17 (plus 90 days), like many Jordanians, they have not been exercising this right. When linked to some frequently correct assumptions about a gerrymandered electoral process, combined with the aforementioned restrictions on political and social activism, their apathy is explicable. The youth appear to understand that their votes are redundant in a non-free political system. As a few young people engaged in a community program noted, they have limited trust in political leaders.33 They feel politicians and national and community leaders are letting them down and acting as gatekeepers that keep them, and especially young women, out.

In 2016, for example, youth voter apathy was widespread and voter participation in the legislative elections in the 17-30 age group was a disappointing 35 percent.34 Thus, only around 525,000 youth participated in the elections. “I did not vote, my brother did not vote, and nor did any of my friends,” commented one Amman-based young man in the wake of the 2016 legislative elections.35 Similarly, a group of young males in the town of Zarqa reported they had no motivation to vote because they assumed their vote would have little effect on public and political life.36 Such attitudes were also apparent in a 2016 University of Jordan voter survey, which indicated that 46 percent of youth said they would definitely not cast their vote in general elections.37

Not surprisingly, such apathy is also present in youth candidacy rates even after the minimum age was reduced to 25 years on the local level. Of the 6,623 candidates who competed for mayoral, municipal, and governorate council seats in 2017, a very modest 6 percent were under the age of thirty and only 14 percent were under the age of forty.38 In the governorate and municipal elections, the youngest three of the elected 299 were 26 years old. The average age was 49.7 years.39 Similarly, of the 99 mayors elected across Jordan, the youngest was 27. The average age in the three provinces with the youngest mayors was 46 years in Madaba, Aqaba, and Kerak.40 Government officials defended these numbers as preliminary results against a background of low public awareness regarding the new election format and decentralization program, but those figures are unlikely to change without addressing the deeper layers of youth exclusion discussed above.41Losing our own: tribal youth

Perhaps the most alarming indicator of the consequences of youth exclusion was the role played by tribal youth activists during the protests that sprung in Jordan in 2011.42 Under the banner of the Hirak movement, tribal youth brought together more than 30 groups from Jordan’s tribal environs to organize and protest against the government and king.43 Through joining the demonstrations, they showed they had more in common with protestors than the state and that they wished to broaden their inclusion through electoral reform and ending corruption.

This development was particularly noteworthy because the monarchy in Jordan has traditionally relied on the tribal loyalty of its East Bank population for legitimacy.44In the past, the compact between state and tribes had centered on forms of economic benefit (chiefly public service jobs and state services) in return for political loyalty. Tribal loyalty, for example, has been a key mechanism in voter turnout in support of the regime Under the Hirak, a key group traditionally sharing in the social compact with the state mobilized to protest against their marginalization.

In fact, the tribal youth are not only challenging the state but also their elders. Hirak leaders are calling for wider rights associated with youth inclusion across the country.45 As one U.S. diplomat in Jordan opined, “The tribal compact in Jordan is under pressure. Tribal youth complain that their elders exclude them from leadership roles. So when the primaries were held, the young guys tried to get themselves on the list [for parliamentary elections] but largely failed.”46 A youth leader confirmed the statement, “We tried to get on the list but we were blocked by our own elders. We ran as independent candidates.”47

This underlines that Hirak reflects important generational tensions and stratified hierarchies of power within and between tribes, as well as between tribes and wider society and politics in Jordan. Hirak symbolizes the powerful impact of youth organization in Jordan and its growing defiance of the state and its leadership. Their activism highlights inter-generational, class, and social distinctions that make the state increasingly vulnerable.48

But their efforts have not been enough to disrupt the electoral stranglehold enjoyed by tribal coalitions populated and headed by an older generation.

Nevertheless, Hirak youth remain defiant. The continuing involvement and organization of and by tribal youth elements in Jordan remains a challenge to power-holders in the state. Their activists have continued to organize protests and forms of engagement for young people. They have mobilized both in Jordan’s urban areas, where the majority of the population reside, but also, in rural areas to the south, north, and east of the country, where tribal affiliations and the ruling bargain with the political elite have traditionally been strongest. The cohesion and engagement of Hirak youth reflected a fundamental challenge from Jordan’s most important social strata.49Youth violence and radicalization

The state, as recognized above, plays an important role in the marginalization of Jordan’s youth. Conflicts among youth and between youth and “governing” authorities have been evident.50 As one senior academic at the University of Jordan noted, “Cohesion is breaking down among our students because the burdens on them are enormous and especially for young men as their frustrations are growing.”51 Such frustration is evident in the growing phenomenon of campus clashes.

In the midst of such uncertainty and insecurity, and with limited channels of expression, youth have become distanced from state and society. While the processes of radicalization are complex and not singular in genesis, such pressures can contribute to pulling some young people closer to violent extremism.52 Studies have estimated that Jordanians are among the top three Arab foreign fighter nationalities in Syria and Iraq, with up to 2,000 recruited to join the Islamic State and other violent extremist groups; the typical age of a fighter is 18-29. 53

Theorists of violent movements understand that a repressive state can fuel recruitment to violent extremist organization. Increasingly, researchers and advocates are recognizing that recruitment to violent extremism in a country like Jordan is associated with the structural barriers erected by government in the face of the aspirations of the young.54 Violence and extremism is rooted in the democratic governance deficit (including associated practices of state repression) and not just, as so many officials claim, in poverty, poor education, and social media messaging.55Issues such as marginalization, corruption, nepotism, education, and unemployment are important factors in youth radicalization.56Recommendations

The policies that can address youth exclusion and marginalization are myriad, but the government, policymakers, and others have transformed the matter into an urgent security concern.57 Many national and internationally supported CVE/PVE programs embrace a reductive approach that treats young people simplistically as potential terrorists. Yet, the issue of violent extremism is linked to wider structural barriers and cannot be addressed by solutions that mainly securitize youth. In fact, such approaches have resulted in growing tensions between the state and youth, commonly alluded to in public discourse on violent extremism.

The recommendations below depart from such approaches and focus on youth mainstreaming in development program aid and assistance. Youth mainstreaming gives priority to youth not just in the development of Jordan’s new strategies but also in the implementation of those strategies. It ensures that the agency of young people be fostered through their participation in community-led initiatives.

The policies below recognize the centrality of youth inclusion and empowerment to address sustainably and effectively issues such as youth political apathy, disaffection among tribal youth, and radicalization. Inclusive policies that recognize the intersectionality between political, civic, and economic development are the only viable approach to these issues

Bolster government-led youth initiatives

Throughout Jordan, the government allocates only limited resources to tackle issues such as youth exclusion, unemployment, and poverty, especially with respect to the most vulnerable youth within society. With the encouragement of the U.N. and other international actors, the Jordanian state must significantly improve and release budgetary resources for youth across government institutions. While Jordan is not as resource rich as many of its Arab counterparts, it can leverage its development funding and assistance partnerships to establish greater linkages between development policies and the implementation of the kinds of structural reforms that service youth and which only the government can implement.

To that end, the government and king should strengthen and better finance the Ministry of Youth (MoY) through directing more resources, prestige, and praise to the severely depleted ministry. Jordan has embarked on developing a National Youth Strategy (2017-2025) under the administrative address of MoY, but there was a fear among youth activists and their supporters that the same kinds of negative stereotyping about youth, which were obvious in its anti-extremism strategy, would prevail. To avoid those suspicions, MoY should be urged not only to include the voice of young people in formulating strategies, but it must give them a role in implementation.

Of course, key youth issues such as employment and participation cannot be funded or implemented properly through the one institutional address of MoY, but rather, a framework of policies is needed that involves all government institutions. As such, international donors should play their part in a Youth Sector Working Group that better links youth policy implementation with the sharing of resources, while also avoiding sectoral replication.

Foster youth political inclusion

Youth voter apathy and the limited opportunities for youth political participation are hindering Jordan and establishing systemic security risks. The upswing in domestic terror attacks and the flow of young Jordanians to Syria since 2011 illustrate the scale of the problem. Jordan’s domestic and international partners must encourage the Jordanian government to develop youth voter awareness campaigns organized not only by the Independent Election Commission or state media, but also by grassroots youth initiatives.

Jordan should also lower the minimum age for candidacy in parliamentary elections to align it with the voting age. Given that the state recognizes youth as an opportunity and “gift” to the nation, it could even be so bold as to include youth quotas in parliamentary and municipal councils in the same way that it has successfully introduced them for women. In Morocco, for example, the 2011 election law included quotas in the legislature for candidates under 40 years old. In Tunisia, new legislation has ensured that each party list includes at least one candidate below the age of thirty.

Such recommendations are not a panacea, but they can begin to challenge national and sub-national political structures and better promote youth political participation and representation. As research for this policy briefing highlights, young Jordanians perceive change in the formal political realm as part of the solution, but they also need activities and spaces that represent greater autonomy and promote “politics from below.”

Promote civic youth

Youth in Jordan are educated but not in ways that promote civic inclusion and participation. It is, therefore, time to establish norms of civic engagemenin state-led curriculum planning Coordination between government ministries to train and support teachers to inspire principles of civic engagement in Jordanians from an early age would also build community resilience against radicalization and extremism.

Civil society actors must play a role in this broader culture shift. The state can lead through example in the hope that societal leaders can follow. Government requirements for NGO or civil and community-based organization registration and licensing could introduce a “youth inclusion” principle that not only encourages an adjustment in political norms but also creates incentives for organizations to follow through and implement inclusive policies.

Indeed, government and NGOs should create and enable spaces in which Jordanian youth can enjoy the right to free expression in order to explore and debate their identities, as well as their place in society. Initiatives that establish a greater number of public spaces that are accessible to youth, beyond university and college campuses, would channel youth activism instead of feeling threatened by it. As explained above, young women, in particular, need more access to both physical and virtual public spaces where they are free to participate in the wider civic discourse without fear.

Ease the school-to-work transition

The Jordanian state has recognized the task it faces in tackling the crisis of youth unemployment. One area of this challenge where progress is vital tackles the transition from school to work.58 Here, the issue is not just with school leavers but college and university graduates too. To date, youth employment-training programs by the National Employment and Training (NET) Company, run by the Jordanian Armed Forces, have not been effective in tackling the problem and incur high costs.59

In this respect, the government must work to enhance vocational opportunities and training such as entrepreneurship, business literacy, and mentoring within secondary and tertiary level education in Jordan – for both women and men. The efficacy of the armed forces in this function is particularly questionable. Instead, public-private and private sector partnerships and interventions should be encouraged to drive this process forward on college and university campuses. The efficacy, however, of such partnerships and interventions must be constantly reviewed to encourage transparency and accountability.

Conclusion

The youth, which make up more than 22 percent of the population in Jordan, are marginalized politically, socially, and economically. The political exclusion of youth extends from the schoolyard to parliament. Their social marginalization stretches from formal NGOs and civil societies to informal tribal networks. Their high levels of unemployment confirm their position at the margins of the economy, both as employees and entrepreneurs. Young women are further excluded by added layers of patriarchy. As a result, many youth have become apathetic and distrustful of the institutions that exclude them. Some, like tribal youth, have become eager to breakdown long-held social compacts that do not serve them. Some have resorted to violent extremism and radicalism.

Tangible steps should be taken to foster youth inclusion in Jordan. This means that the government must move beyond rhetoric to implementation and actively include young people and wider society in the process. However, the Jordanian state cannot undertake this task alone. Other societal forces, including tribes and religious leaders, must let youth in too. Furthermore, the government needs the continued and active assistance of partners, such as the United States, and the European Union, with whom it has strong relationships. Regional state actors and international organizations should also offer their continued support. Assistance from those partners should include rigorous conditionalities concerning youth inclusion to help the Jordanian government move forward on the matter. Without the inclusion of Jordan’s youth, it will be all but impossible for King Abdullah’s government to secure the future stability of the country.

-

Footnotes

- The youth are defined here as persons between the age of 15 and 24. U.N. Secretary-General’s report to the General Assembly, A/36/215, 1981. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf (accessed July 7, 2017); United Nations Development Program (UNDP), “About Jordan,” http://www.jo.undp.org/content/jordan/en/home/countryinfo.html#Population%20and%20Economy; (accessed November 15, 2016); for the chart, see CIA, “The World Factbook (Jordan),” last updated March 14, 2018, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/jo.html (accessed March 14, 2018).

- The author conducted interviews with Jordanian government officials, experts, and local and international NGO actors that focus specifically on youth programming and youth initiatives, as well as western government officials, student leaders, youth, and youth activists, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. The interviews took place in Amman and Zarqa, Jordan, in 2016 and 2017.

- Marriage is important for young people because adulthood is defined by milestones such as establishing a home and becoming more independent financially. In Jordan, the cost of a wedding is beyond average means, and the age at which Jordanians are marrying is being delayed. See: Nadine Ajaka, “Waiting Longer to Marry,” Aljazeera, May 2, 2014, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2014/02/waiting-longer-marry-jordan-201421972546802626.html; UNDP, “Arab Youth Strategising for the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs),” 2006, http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unyin/documents/arabyouthmdgs.pdf.

- Maria Josua, “Co-optation Reconsidered: Authoritarian Regime Legitimation Strategies in the Jordanian ‘Arab Spring,’” Middle East Law and Governance 8, no.1 (2016): 32-56; Ellen Lust-Okar, “Elections under Authoritarianism: Preliminary Lessons from Jordan,” Democratization 13, no. 3 (2006): 456-471.

- Western government official, interview with author, Amman, Jordan, October 18, 2017.

- Student leader, interview with author, Zarqa, Jordan, April 25, 2017.

- Beverley Milton-Edwards, “Protests in Jordan over Gas Deal with Israel Expose Wider Rifts,” Markaz (blog), Brookings Institution, October 26, 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2016/10/26/protests-in-jordan-over-gas-deal-with-israel-expose-wider-rifts/.

- “Hashemite University Students Protest Expelling of Ibrahim Obeidat,” al-Ghad, November 10, 2016, http://www.alghad.com/articles/1243472-Hashemite-University-Students-Protest-Expelling-of-Ibrahim-Obeidat.

- Thabahtona translates to “you slaughtered us.”

- Student leader, interview with author, Zarqa, Jordan, April 25, 2017.

- Mukhabarat translates to state intelligence. Young Jordanian rapper, interview with author, Amman, Jordan, October 20, 2017.

- Young concert producer, interview with author, Amman, Jordan, October 19, 2017.

- Sameer Jarrah, “Civil Society and Public Freedom in Jordan: The Path of Democratic Reform,” The Saban Center for Middle East Policy, Brookings Institution, Working Paper No. 3, July 2009, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/07_jordan_jarrah.pdf.

- “Jordan Builds on Previous Electoral Achievements to Boost Democracy,” Independent Elections Commission, June 15, 2017, https://iec.jo/en/content/%E2%80%98jordan-builds-previous-electoral-achievements-boost-democracy%E2%80%99.

- The World Bank estimated GDP per capita in Jordan for 2016 at only USD 4,000, making the deposit (plus other election expenses for campaigning) prohibitive. See: World Bank Statistical Database, “GDP per Capita (Current $US),” accessed March 7, 2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD.

- U.N. Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia and the U.N. Program on Youth., “Regional Overview: Youth in the Arab Region,” Dialogue and Mutual Understanding, International Year of Youth August 2010-11, https://social.un.org/youthyear/docs/Regional%20Overview%20Youth%20in%20the%20Arab%20Region-Western%20Asia.pdf; OECD, “How to Engage Youth in Jordan’s National Youth Strategy 2017-25,” G7 Deauville Partnership MENA Transition Fund Project, March 1, 2017, http://www.oecd.org/mena/governance/How-to-engage-youth-in-Jordan-National-Youth-Strategy.pdf.

- National Center for Human Rights, “Annual Reports,” Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 2016, http://www.nchr.org.jo/english/Publications.aspx.

- Paul Tacon, “Youth in the ESCWA Region: Situation and Responses,” Youth Policy, 2011, http://www.youthpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/library/2011_Youth_In_ESCWA_Region_Eng.pdf.

- In 2011, youth activists wrote “the people want reform of the regime” on Jordanian banknotes. See, “Youth Mobility: People Want Reform on Banknotes,” Jordanzad, July 18, 2011, http://www.jordanzad.com/index.php?page=article&id=49902.

- World Bank Statistical Database, “Youth Unemployment Rates 1991-2016,” accessed March 7, 2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS?locations=JO&view=chart.

- “PM Visits Luminus Group Vocational Training Colleges,” Jordan Times, September 18, 2017, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/pm-visits-luminus-group-vocational-training-colleges.

- “Education, Labour Ministries Join Forces to Encourage Enrolment in Vocational Training,” Jordan Times, June 28, 2016, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/education-labour-ministries-join-forces-encourage-enrolment-vocational-training.

- Mohammad Ta’Amnha, Susan Sayce, and Olga Tregaskis, “Wasta in the Jordanian Context,’ in Handbook of Human Resource Management in the Middle East, eds. Pawan Budhwar and Kamel Mellahi (Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016).

- Gallup World Poll Survey 2013 cited in Jumana Alaref, “Wasta Once Again Hampering Arab Youth Chances for a Dignified Life,” World Bank (blog), March 13, 2014, http://blogs.worldbank.org/arabvoices/wasta-hampering-arab-youth-chances-dignified-life.

- See for example Jordan’s poor ranking for ease of doing business by the World Bank: Omar Obediat, “Kingdom Ranked 113th out of 189 Countries for Ease of Doing Business,” Jordan Times, October 29, 2015, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/kingdom-ranked-113th-out-189-countries-ease-doing-business-report.

- Dina Kiwan, May Farah, Rawan Anna, and Heather Jaber, “Women’s Participation and Leadership in Lebanon, Jordan, and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq: Moving from Individual to Collective Change,” Oxfam, April 25, 2016, https://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/womens-participation-and-leadership-in-lebanon-jordan-and-kurdistan-region-of-i-604070.

- World Bank, “Country Gender Assessment: Economic Participation, Agency, and Access to Justice in Jordan,” July 1, 2013, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/503361468038992583/Country-gender-assessment-economic-participation-agency-and-access-to-justice-in-Jordan.

- Rana Husseini, “House Maintains Women’s Quota in Elections Bill at 15 Seats Despite Demands for 23 Seats,” Jordan Times, February 22, 2016, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/house-maintains-women%E2%80%99s-quota-elections-bill-15-seats-despite-demands-23-seats; Assaf David and Stefanie Nanes, “The Women’s Quota in Jordan’s Municipal Councils: International and Domestic Dimensions,” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 32, no.4 (November 2011): 275-304, https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2011.613709.

- “Significant Increase in Female Unemployment Rate in Jordan,” Roya TV, July 13, 2017, http://en.royanews.tv/news/10778/2017-07-13.

- World Bank Statistical Database, “Unemployment, Youth Female (% of Female Labor Force Ages 15-24),” accessed March 12, 2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.FE.ZS?end=2016&locations=JO&start=2008&view=chart.

- Mayyada Abu Jaber, “Breaking Through Glass Doors: A Gender Analysis of Womenomics in the Jordanian National Curriculum,” Center for Universal Education, Brookings Institution, December 2014, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/EchidnaAbu-Jaber2014Web.pdf.

- Jordan Strategy Forum, “Job Creation in Jordan: Emphasizing the Role of the Private Sector,” September 2016, http://jsf.org/sites/default/files/EN%20-%20Job%20Creation%20in%20Jordan%20-%20Emphasizing%20the%20Role%20of%20the%20Private%20Sector%20(2).pdf.

- Anonymous, focus group by author, Jordan, 2017.

- This compares to a participation rate of 36.1% overall. See: European Union Election Observation Mission, “The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: Parliamentary Election 20 September 2016,” Final Report, November 13, 2016, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu_eom_jordan_2016_final_report_eng.pdf.

- Mahmoud Jawabreh, interview with author, Amman, Jordan, December 6, 2016.

- A group of young men, interviews with author, Zarqa, Jordan, December 5, 2016.

- Khetam Malkawi, “Less than 40% of Jordanians Plan to Vote on Tuesday – Poll,” The Jordan Times, September 17, 2016, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/less-40-jordanians-plan-vote-tuesday-%E2%80%94-poll.

- Rased, “Statement on the Educational, Professional, and Ages of Mayors,” September 17, 2017, http://www.hayatcenter.org/uploads/2017/09/20170924131846en.pdf.

- “299 Members Won Governorate Council Elections – Watchdog,” September 9, 2017, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/299-members-won-governorate-council-elections-%E2%80%94-watchdog.

- Rased, “Statement on the Educational.”

- Official at the Ministry of Political and Parliamentary Affairs, interview with author, Amman, Jordan, November 1, 2017.

- For more on Hirak and its emergence, see: Sean, L. Yom, “Tribal Politics in Contemporary Jordan: The Case of the Hirak Movement,” The Middle East Journal 68, no .2 (2014): 229-247. There are assertions that within the umbrella of the Hirak, Palestinian-Jordanians were active but deliberately concealed their participation due to the nature of regime-Palestinian relations. See: E.J. Karmel, “How Revolutionary Was Jordan’s Hirak? What the Incognito Participation of Palestinian-Jordanians in Hirak Tells US about the Movement,” Identity Center, June 2014, http://identity-center.org/sites/default/files/How%20Revolutionary%20Was%20Jordan’s%20Hirak__0.pdf.

- Sean L Yom and Wael Al-Khatib, “Jordan’s New Politics of Tribal Dissent,” Foreign Policy, August 2, 2012, http://foreignpolicy.com/2012/08/07/jordans-new-politics-of-tribal-dissent/.

- Beverley Milton-Edwards and Peter Hinchcliffe, Jordan: A Hashemite Legacy (London: Routledge, 2009).

- Daniel P. Brown, “How Far ‘Above the Fray’? Jordan and the Mechanisms of Monarchical Advantage in the Arab Uprisings,” The Journal of the Middle East and Africa 8, no. 1 (2017): 97-112.

- U.S. official, interview with author, Amman, Jordan, December 5, 2016.

- Anonymous tribal youth leader, interview with author, Jordan, October 18, 2017.

- Pascal Debruyne and Christopher Parke, “Reassembling the Political: Placing Contentious Politics in Jordan,” in Contentious Politics in the Middle East (New York: Palgrave 2015), 437-465.

- Sean L. Yom, “Tribal Politics in Contemporary Jordan: The Case of the Hirak Movement,” The Middle East Journal 68, no.2 (2014): 229-247.

- Omaymah Al Harahshed, “Addressing Campus Violence Remains Unfinished Business as Debate Goes on,” Jordan Times, September 5, 2017, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/addressing-campus-violence-remains-unfinished-business-debate-goes.

- Professor Ayman Khalil, interview with author, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan, December 6, 2016.

- Radicalization Awareness Network, “The Root Causes of Violent Extremism,” RAN Issue paper, April 2016, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/ran-papers/docs/issue_paper_root-causes_jan2016_en.pdf.

- “Foreign Fighters: An Updated Assessment of the Flow of Foreign Fighters into Syria and Iraq,” The Soufan Group TSG, December 2015, 8, http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/TSG_ForeignFightersUpdate3.pdf; Richard Barrett, “Foreign Fighters in Syria,” The Soufan Group TSG, June 2014, 15, http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/TSG-Foreign-Fighters-in-Syria.pdf.

- Steven Heydemann, “Countering Violent Extremism as a Field of Practice,” Insights 1, U.S. Institute of Peace, 2014, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/Insights-Spring-2014.pdf.

- Perry Cammack, “To Address a Turbulent Arab World, Start with Governance,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 3, 2015, http://carnegieendowment.org/2015/12/03/to-address-turbulent-arab-world-start-with-governance-pub-62095.

- Neven Bondokji, Kim Wilkinson, and Leen Aghabi, “Trapped Between Destructive Choices: Radicalization Drivers Affecting Youth in Jordan,” WANA Institute, February 21, 2017, http://wanainstitute.org/en/publication/trapped-between-destructive-choices-radicalisation-drivers-affecting-youth-jordan.

- Mercy Corps, “From Jordan to Jihad: The Lure of Syria’s Violent Extremist Groups,” Policy Brief, September 28, 2015, https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/From%20Jordan%20to%20Jihad_0.pdf .

- International Labor Organization, “Youth in Jordan Face Difficult Transition from School to Decent Work,” Study, July 21, 2014, http://www.ilo.org/beirut/media-centre/news/WCMS_249778/lang–en/index.htm.

- Thoraya El-Rayyes, “Employment Policies in Jordan,” European Training Foundation (ETF), 2014, http://www.etf.europa.eu/webatt.nsf/0/8D5C3712F2457914C1257CD000505340/$file/Employment%20policies_Jordan.pdf.