The emergence of ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft seems to pose a direct challenge to the nation’s overburdened and underfunded transit agencies, potentially siphoning off patrons most able to pay full fare. Yet, amid competition, there exists a real opportunity for collaboration in providing mobility to the agencies’ neediest customers.

American public transit needs the help. While systems from Charlotte to Houston to Seattle are building new capacity and connectivity, many also face tight budgets and enormous debt burdens, leading to service cuts and increased fares. In Memphis, the transit authority is on the verge of fiscal collapse. Other agencies in Los Angeles and Washington are experiencing lower demand, and many new riders still live too far from high-frequency service or struggle to access jobs and other services via transit.

Amid these difficulties, however, new service providers—transportation network companies (TNCs)—are shifting how people move around our cities and offering mobility solutions through a series of ride-hailing innovations.

One avenue for collaboration between these start-up firms and traditional transit agencies may be around so-called demand response services. Primarily geared toward disadvantaged individuals, these taxi-like services provide a lifeline to needy residents in urban and rural areas. But they also carry a heavy cost, and transit agencies from Boston to Washington are starting to look toward TNCs as a potential partner. The long-term implications of arrangements like these involve a number of structural issues that transportation leaders need to confront.

Grappling with the cost of demand response services

Mandated under federal law, demand response (DR) services provide assistance for persons with limited mobility, allowing them to reach services like healthcare providers and grocery stores. Also called paratransit and dial-a-ride in many areas, DR services do not operate over a fixed schedule like a standard public bus; rather, vehicles are dispatched on request and operate door-to-door. In many ways, DR services represent a progenitor of mobile app-based TNCs.

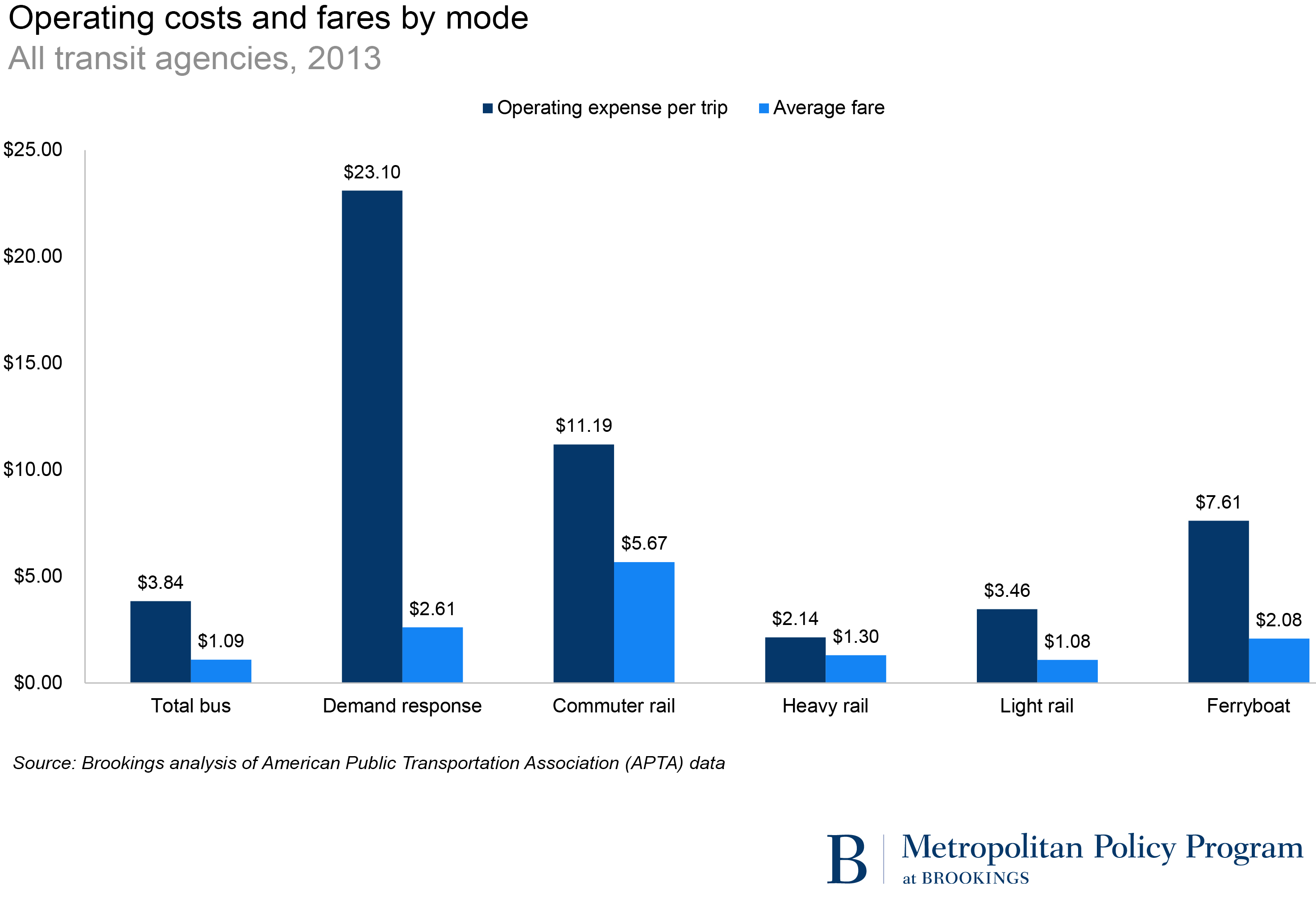

Such service is costly, though. From outdated technology to the difficulty in coordinating options among multiple transportation providers, DR services are the most expensive mode to operate on a per trip basis, exceeding $23 in 2013. Federal regulations limit the fares transit agencies can collect for DR services to double a regular bus ride, leaving transit agencies with enormous cost gaps and the highest subsidies per passenger of any transportation mode (what experts call the farebox recovery ratio).

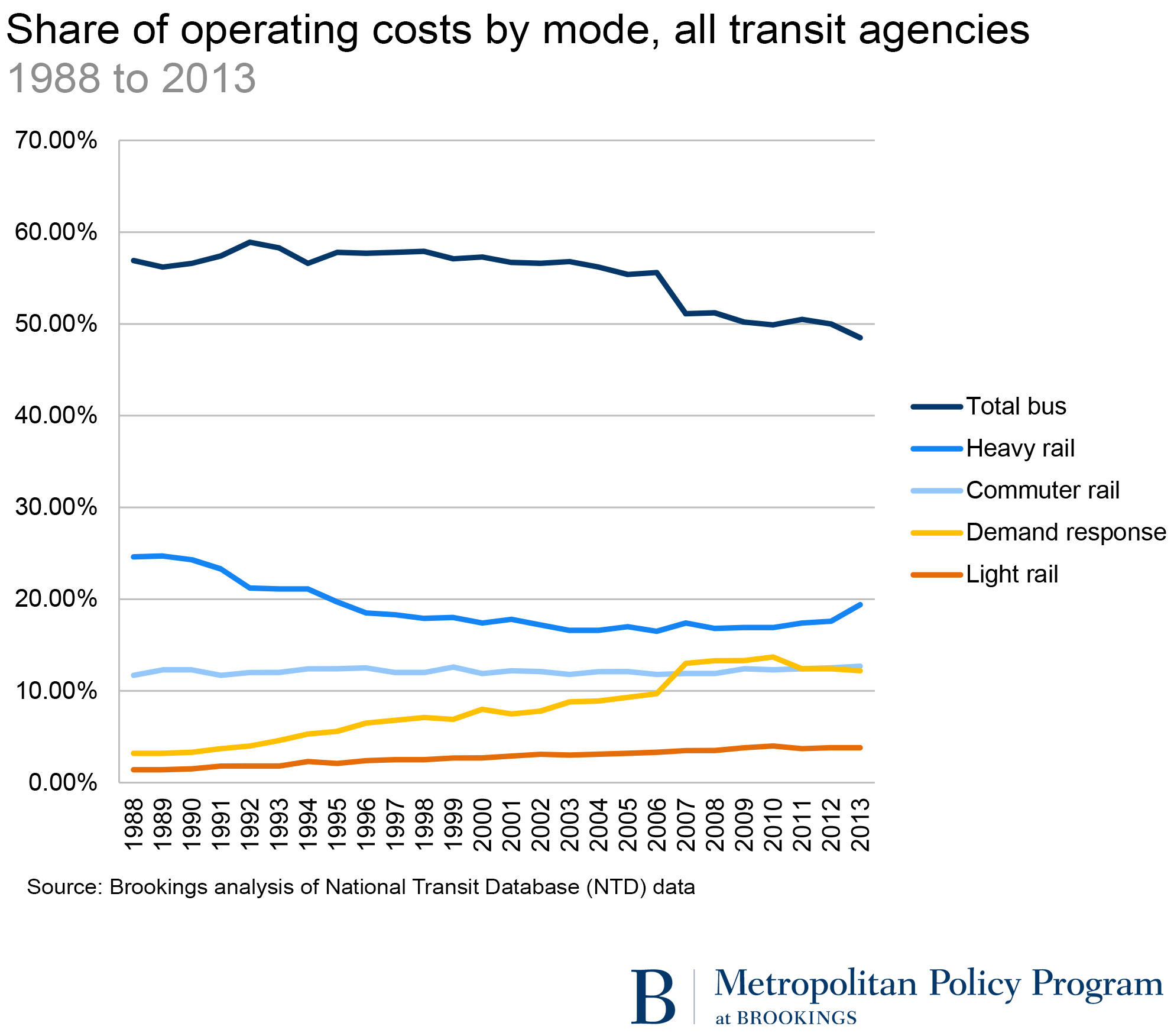

Even more concerning is how DR costs have ballooned over time as demand continues to grow. In 2013, DR services cost $5.2 billion, or 12.2 percent of the total for all transit services. By comparison, it only represented 3.2 percent of all costs in 1988 and has easily seen the largest rise in expenses of any transit mode. These escalating costs come despite the fact that DR services carry only about 2 percent of all transit trips; commuter rail generates relatively high operating costs as well, but carries 4.5 percent of all riders by comparison.

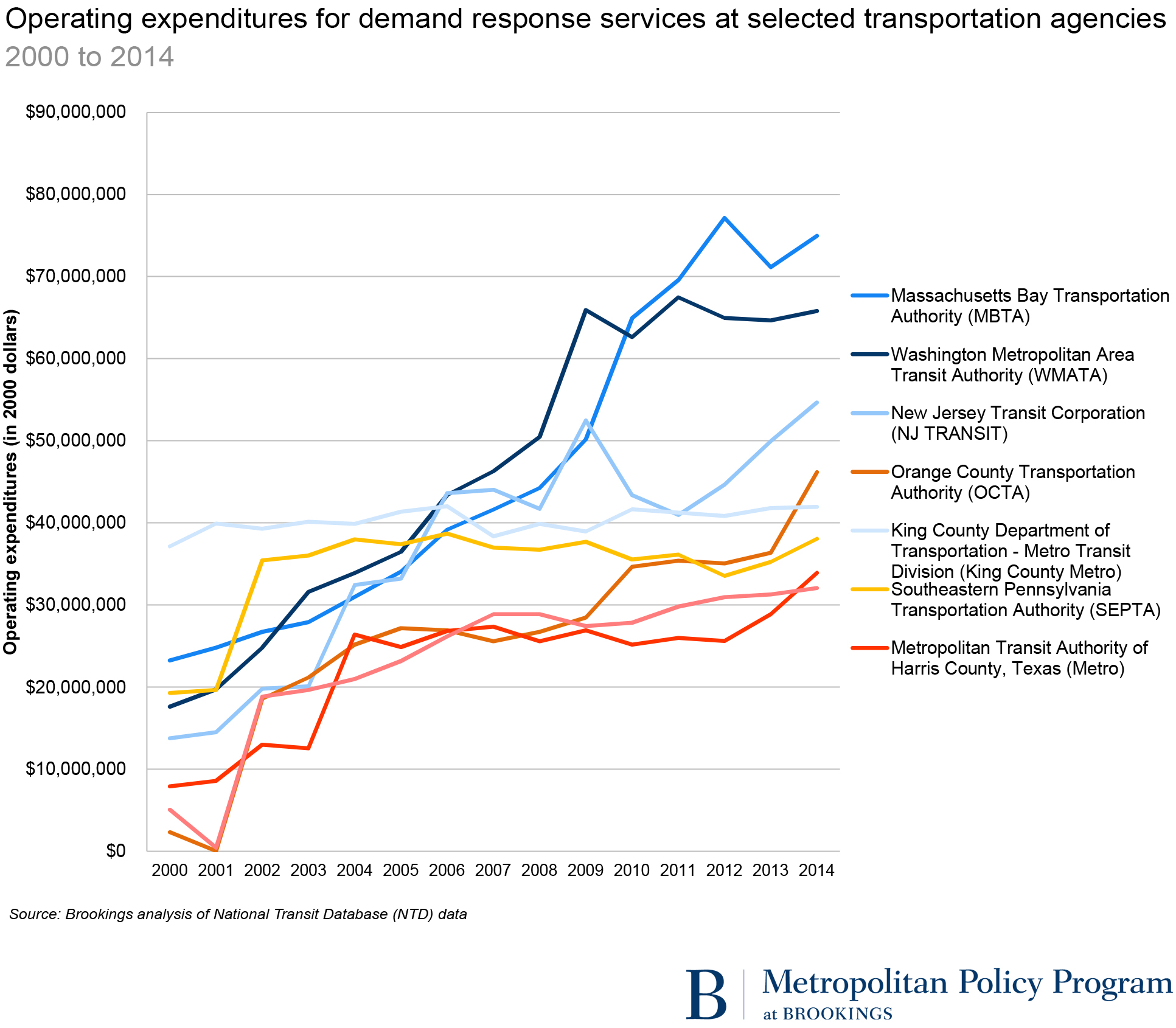

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), New Jersey Transit Corporation (NJ Transit), and the Denver Regional Transportation District (RTD) are among multiple agencies that have seen DR costs almost quadruple from 2000 to 2014, when adjusted for inflation. While not shown in the figure, New York City Transit (NYCT) faces the highest operating costs in this category, rising to nearly $456 million in 2014, versus under $20 million less than two decades ago.

Together, the high costs and growing demand for DR services puts a strain on transit agency budgets—already spread thin for other needed improvements—and represents a long-term fiscal challenge.

A market-based solution

The tantalizing prospect, then, is to consider ride-hailing services as a new outlet for cost savings and improved access.

These transportation network companies launched with a fairly narrow focus on taxi-like rides but have started to offer a greater range of services that complement or outright compete against traditional transit. For example, Lyft has launched a “Friends with Transit” initiative to forge stronger, more convenient links for a growing number of riders in Boston, Chicago, and elsewhere. Both Uber and Lyft synchronize with transit agency mobile apps in Dallas and Atlanta. Meanwhile, there is a surge in TNCs offering a mix of ride-hailing and transit services, often called microtransit, including a new service agreement between Kansas City and one such company, Bridj.

Transit agencies may want to explore contracting-out DR services to TNCs. Beyond minimizing costs through their software platforms and efficiently deploying drivers to customers, TNCs can probably update technologies faster than traditional public transit agencies. Riders could also benefit, free from worrying about the need to schedule days in advance. Many analysts agree that opportunities exist to improve current DR and paratransit services.

The hypothetical math works, too. If the average DR trip provided by a TNC costs $13 on average, this would generate marginal savings of $10 per ride for transit agencies. If the cost was closer to $18 per ride, that’s still a net reduction of $5 per ride. Multiplying those savings against the 223 million trips per year, transit agencies would free up $1.1 to $2.2 billion in their operational budgets. These kinds of savings would have an enormous impact on overall transit performance, whether increasing vehicle frequency, adding new routes, or simply reducing the aggregate subsidy to run individual agencies.

Overcoming potential roadblocks

Still, several thorny issues remain unresolved and may complicate a transition to TNC-provided services. Organized labor may oppose the transition from unionized staff to independent contractors, and disability advocates contend that companies like Uber are already in violation of federal laws mandating equal access. Smartphone penetration is weak among lower-income and elderly individuals, which may portend problems with DR customers accessing TNC services. Coordination is already an issue between multiple transit agencies offering DR service in one place, meaning there could be governance challenges if each agency must separately contract with a single TNC.

Finally—and perhaps most importantly—no one knows if TNCs can even provide DR services for lower marginal costs. Recent estimates of Uber and Lyft fares tend to average around $13, albeit with wide differences in cost depending on the particular service used. But is that average ride comparable to a typical DR trip? Are there enough vehicles available to meet the physical needs of DR customers? Recognizing that TNCs will need to pay drivers a competitive rate while still generating a profit, transit agencies will need to weigh subsidy costs carefully.

Conclusion

The ability of TNCs to deliver point-to-point mobility for relatively low costs has the potential to align quite well with public transit agencies that are struggling to address the mounting costs of DR services and meet the increasing demand for conventional fixed route services. In the short term, exploring these arrangements can benefit providers and customers in many ways.

Longer term, solving the DR riddle could lead to more effective, robust partnerships between transit agencies and TNCs. Whether it’s new coordination around first-and-last mile service or sharing data on ridership patterns, a future where transit agencies and TNCs seamlessly work together to maximize social benefit is the real innovation we should be seeking.