Abstract

Research suggests that having a car is a worthwhile investment in better outcomes for low-income families. Recent reports quantify the additional money required to own and operate personal vehicles, as compared to the lower cost of traveling on public transit. However, this method of accounting fails to consider the fact that poor workers without a car may not be able to search for or accept a better-paying job because public transit doesn’t take them there, causing these workers to lose income or benefits as a result. This report outlines opportunity costs experienced by transit-dependent poor households, and concludes that when all costs are considered along with benefits of private vehicles, it makes sense to press for more assistance and policies that reduce car ownership costs for poor workers.

CCF Brief # 35

The typical parent who leaves welfare for work earns about $8 an hour. Many such parents are eligible for publicly funded work supports like child care, food stamps, Medicaid, and the Earned Income Tax Credit, but few poor families get all the support they are eligible to receive. In addition, as they struggle to meet family needs, poor parents face transportation complications, including lengthy commutes on public transit. For these financially stressed families, the cost of buying and maintaining a car can create difficult financial tradeoffs. Yet, the opportunity cost of going without one weighs heavily on these poor households.

The High Cost of Public Transit

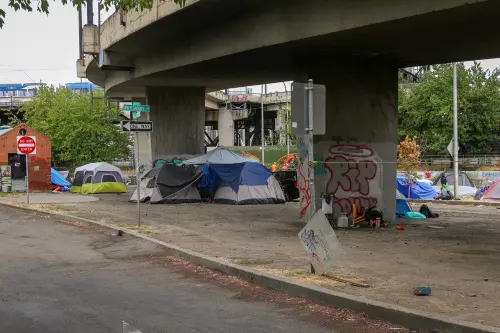

Making do without a reliable car requires poor households to rely on others or on the local public transit system. Public transit can work well for poor workers in dense urban areas, and its advocates proclaim that transit reduces sprawl and congestion and leads to better air quality. Yet, in 2000, fewer than 5 percent of workers took public transportation to work, while nearly 88 percent commuted by car. Despite significant public investment in public transit, usage continues to decline as a percentage of urban travel. Nevertheless, poor workers are more likely to commute by public transit—especially bus—than are higher income workers. Transit-dependent low-income households often pay a high price for going without a personal vehicle as transit often fails to meet their needs.

The poor represent a higher percentage of bus riders than subway riders, and a higher percentage of subway riders than commuter rail riders. While many new jobs are located in the suburbs, public transit rarely takes central city residents all the way to the door of suburban employers. Consequently, a car or another means of transportation is required to take workers from the rail stop to the suburban job. Fortunately, there are still many jobs for entry-level workers in cities, providing a rationale to invest in public transit for densely populated urban areas with a high concentration of employers and housing. Unfortunately, low-income riders are often underserved by central city transit systems as policymakers cut funds for heavily utilized inner-city bus lines in order to subsidize the more costly suburban commute.

In recent years, transit investment has tended to focus on rail services over buses, and suburban commuters over city riders. A 1981 study revealed that the per passenger public operating subsidy for commuter rail was at least three times more than for bus service. Since then, much of the public investment for capital expenses has targeted rail transit rather than buses. Unfortunately, extending rail service does little to meet the needs of low-income commuters, while improving frequency of service on heavily traveled inner-city bus and subway routes can do more to meet the needs of transit-dependent low-income workers than increasing reverse-commute options.