Last month, a landmark immigration reform bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate that has the potential to both increase the number of available H-1B visas for foreigners working in specialty occupations and shift the U.S. employment-based visa system to a more merit-based scheme favoring science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) workers.

As it stands today, businesses say they cannot find the skills they need in the domestic labor pool and need access to a global pool of STEM workers. Bolstering their contention are a number of studies that suggest that STEM jobs exhibit characteristics of under-supply: high wages and low unemployment.

Yet, some analysts have argued that there are plenty of U.S. native-born workers who can do these jobs. They claim that H-1B workers do not have special skills but instead are preferred because they are paid lower wages.

Without attempting to fully resolve this complex issue, new detailed data on H-1B wages by occupation, presented more fully here, suggests that the H-1B program helps to fill a shortage of workers in STEM occupations.

Employers request H-1B visas for hard-to-fill STEM jobs. The vast majority—90 percent—of H-1B applications are for jobs requiring high-level STEM knowledge. This finding is based on our analysis of Department of Labor survey data on the knowledge needed to perform occupations. The evidence shows that these vacancies are harder-to-fill than other job openings.

Labor market experts interpret the duration of a job opening as an indicator that qualified candidates are hard to find. Such an interpretation of vacancy survey data is empirically grounded in both historical and many contemporary labor market surveys from private firms and state governments.

Using 2011 job openings data from the Conference Board for the 100 largest metropolitan areas, we find that 43 percent of job vacancies for STEM occupations with H-1B requests are reposted after one month of advertising, implying that they are unfilled. By contrast 38 percent of vacancies in non-STEM occupations requiring a bachelor’s degree go unfilled after one month, and just 32 percent of job postings for all non-STEM occupations. In a statistical analysis of over 50,000 openings, we find that those requiring STEM knowledge take significantly longer to fill, even controlling for requirements for education, experience, training, and managerial knowledge, as well as wage rates and metropolitan area location. The most commonly requested H-1B occupations in each metropolitan area also take longer to fill.

H-1B visa holders earn more than comparable native-born workers. H-1B workers are paid more than U.S. native-born workers with a bachelor’s degree generally ($76,356 versus $67,301 in 2010) and even within the same occupation and industry for workers with similar experience. This suggests that they provide hard-to-find skills.

To reach this conclusion, we analyzed 2010 H-1B petitions obtained from labor economists Magnus Lofstrom and Joe Hayes through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request filed at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. We combined these data with micro-records from the American Community Survey to compare employed the U.S. native-born with a bachelor’s degree to their H-1B counterparts.

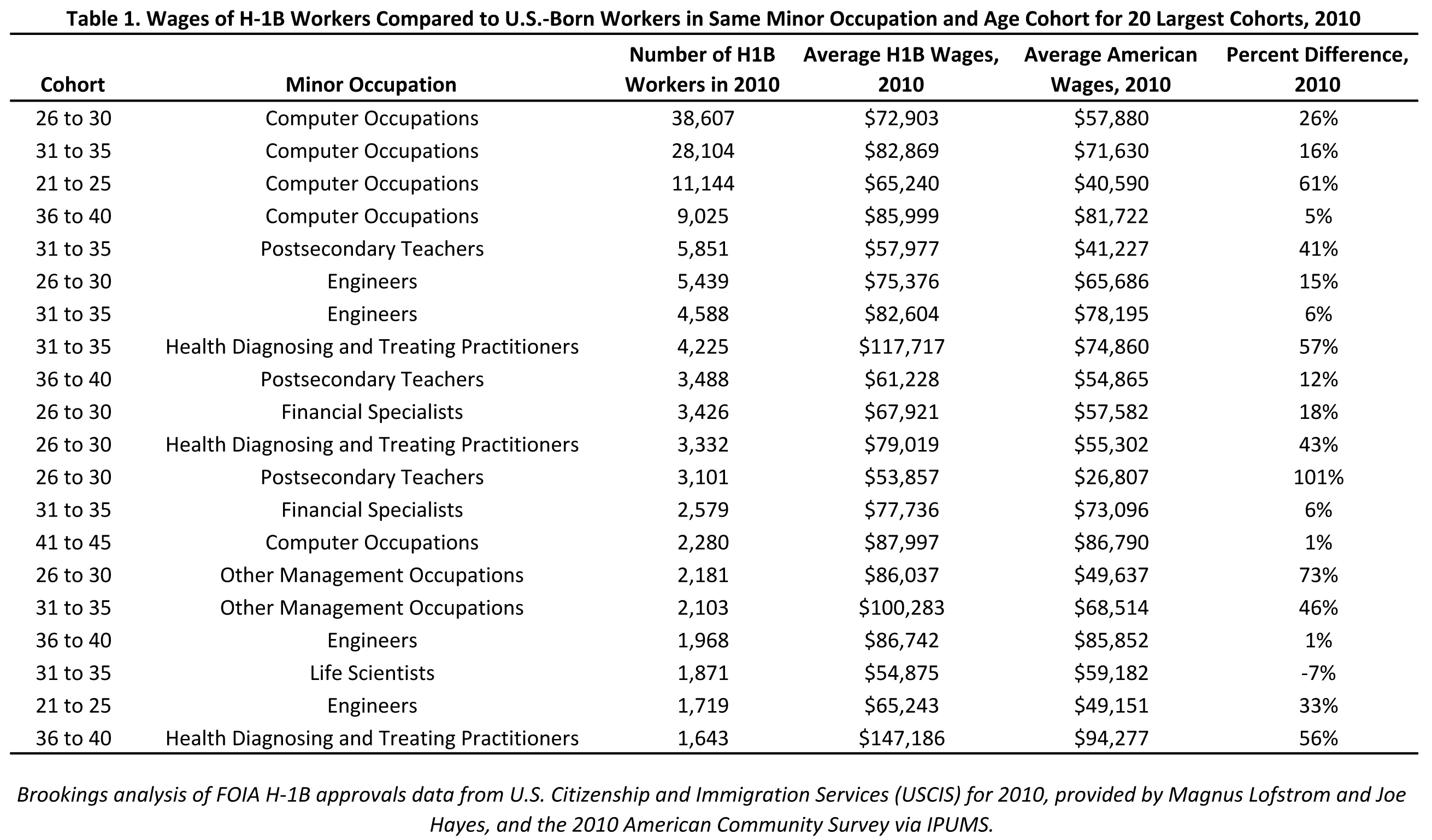

Like Lofstrom and Hayes, we find that H-1B workers earn more than Americans in the same occupation and age cohort. The 20 most common cohort-minor occupation combinations found in the H-1B program are listed below. These groups comprise roughly three-quarters of all H-1B workers in the database. In 17 of the 20 groups, wages are significantly higher for H-1B workers, and there is a significant negative difference only for life scientists aged 30 to 35. For the three largest computer occupation groups, wages are much higher.

Download this data (PDF) »

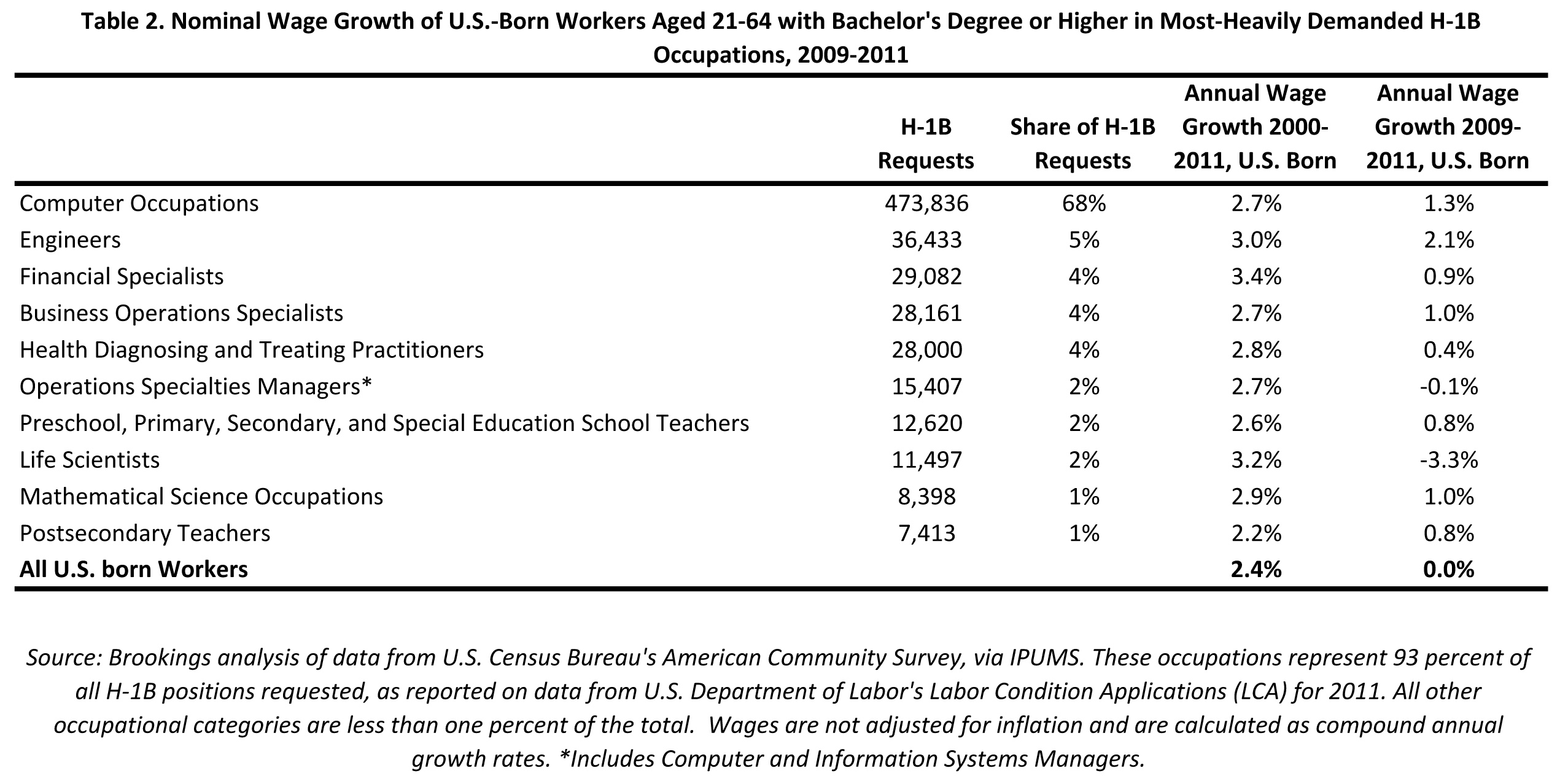

Wages are increasing in occupations with most H-1B requests. In recent years, from 2009 to 2011, nominal wage growth for U.S.-born workers with at least a bachelor’s degree has been high for the most prominent H-1B occupations. The average native-born worker experienced flat annual growth in wages over that period (0.0 percent), but wage growth for those in computer occupations—the largest H-1B category—grew by 1.3 percent each year since 2009 and 2.7 percent each year since 2000 for those with a bachelor’s degree. Wage growth was even higher for engineers, with 2.1 percent growth since 2009 and 3 percent growth since 2000.

For every prominent H-1B occupational category except life scientists and operations specialties managers, wage growth was stronger than the national average since 2009. Since 2000, all but postsecondary teachers have seen higher than average wage growth.

There are two important caveats. First, hard-to-fill high-skilled jobs do not always require many years of post-secondary training. Even among H-1B visa requests, about 25 percent are for occupations that typically require only an associate’s degree, meaning that the current U.S. workforce could be trained to do these jobs at relatively little cost. Second, not all STEM jobs are experiencing the same symptoms of shortage.

A data-driven bureau is needed to identify occupational shortages. Overall, there is compelling evidence that the H-1B visa program is helping to alleviate acute shortages in various occupations. Yet, because of data limitations, the evidence is far from complete. If the Senate bill is passed into law, the proposed Bureau on Immigration and Labor Market Research should collect better information from employers about job openings, including occupations, the number of qualified applicants, the number of interviews conducted, and the length of time it takes to fill the job. Likewise, the bureau should also consider how demand and supply play out in regional or metropolitan area labor markets, since job search and recruitment often happen locally. Armed with such information, as well as indicators presented above, visas and public funding for training and education in hard-to-fill occupations could be more confidently allocated.