As countries around the world fall into a recession due to the coronavirus, what effects will this economic downturn have on Africa? Brahima S. Coulibaly joins David Dollar to explain the economic strain from falling commodity prices, remittances, and tourism, and also the consequences of a recent G-20 decision to temporarily suspend debt service payments for Africa’s poorest countries. Coulibaly emphasizes that the G-20’s actions were an important first step, but more must be done to guarantee countries have the financial resources they need to fight the pandemic.

Related content:

Africa needs debt relief to fight covid-19

Covid19 and Debt Standstill for Africa: The G20’s action is an important first step

China’s Belt and Road: The new geopolitics of global infrastructure development

Understanding China’s Belt and Road infrastructure projects in Africa

Is sub-Saharan Africa facing another systemic debt crisis?

China and Africa’s debt: Yes to relief, no to blanket forgiveness

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

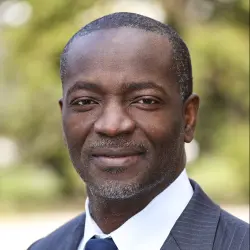

DOLLAR: Hi, I’m David Dollar, host of the Brookings trade podcast, Dollar & Sense. Today our topic is the effect of the Cold War 19 pandemic on African countries. My guest is Brahima Coulibaly, director of the African Growth Initiative at Brookings. He’s about to take over as Vice President of Global Development at Brookings. So congratulations, Coul, and welcome to the show.

COULIBALY: Thank you, David, for having me. I look forward to discussing this pandemic and its effect on Africa.

DOLLAR: So if I look at the map of coronavirus cases around the world, Africa looks okay. As I count, there are only four countries that have 1,000 or more infections: Algeria, Egypt, Ghana and South Africa. So Africa seems to be doing okay. Is that correct? And what are the public health measures that Africa needs to take to protect itself?

COULIBALY: Yeah, I think that’s right. As you noted, indeed, the number of cases for Africa look relatively low. And to the extent that this reflects the reality on the ground – I certainly hope it does – then it is really very good news. But the low numbers could also reflect two important factors.

The first is that Africa was the last region to really register its first cases of COVID. So the infection curve are still on the upward trajectory, and if we look at the past days and weeks, we’ve seen a significant increase in the number of cases. They only had three as of early March, but as of yesterday there were over 35,000 cases, 1,500 deaths and 52 countries. And it’s actually increasing rapidly and we’re not seeing signs yet of flattening of the curve. So that’s the first observation.

The second is the testing capacity remains very low, and unless you’ve really tested widely, you cannot be certain how widespread the virus is. So it is important to also boost detection capacities and encourage the population to actually go to hospital clinics when they begin to feel the symptoms. But as you know, the healthcare capacities and health infrastructure is very limited; one hospital per hundred thousand people, and it’s inaccessible even to 60 percent of the population that is in need in a rural area. So an approach would really be to step up testing units throughout the countries and even create some mobile testing units that can go to the population that does not have access to the health infrastructures. Now we’re seeing some positive signs that the countries are moving in that direction and innovating to provide widespread testing.

DOLLAR: So let’s turn to the economic effect of the crisis. With the United States, China, and Europe all going into very serious recessions, this is having a big effect on world trade. Volumes are down and prices of commodities are down very dramatically. We actually saw the price of oil turn negative briefly last week, and that might be something of an anomaly, but in general the price of fuel, minerals, even food, all of these are down. And a lot of developing countries, including in Africa, export these commodities. So what’s happening to African economies as a result of this crisis?

COULIBALY: I think there’s no doubt the drop in commodity prices will have significant consequences for the economies. But I think in Africa’s case – I usually say that we have a health crisis, we have an economic crisis – in Africa’s case, the economic crisis actually preceded the health crisis because it started out in the advanced economies and also in China. Africa began to feel the effects before it started to register a significant number of cases on the continent. And indeed, the drop in oil prices has been quite sizeable and even larger than the shock we saw in 2014-2015. But back then, it took seven months for prices to drop by about 55 percent. This time around, within three months already it was down by that magnitude. So clearly the commodity dependent economies will see contractions of their GDPs and growth for this year. That includes, regrettably, some larger countries like Nigeria and Angola.

But besides the oil prices, I think remittances are also important to many countries, accounting for more than 5 percent of GDP. For 2018, for example, the region will receive about 85 billion dollars in remittances. To give you some context, that’s actually more than the 50 billion or so in official development assistance to the region. But some early statistics coming out of some transfer companies from Britain to East Africa are already showing an 80 percent drop in orders. And then similarly for Italy, we’re seeing drops of about 90 percent. So if this is representative of what the aggregate number would look like, I would say this would be a significant consequence for the economies.

The other sector that’s going to suffer quite a lot would be the tourism sector, which is critical for many countries, accounting for 5-10 percent of GDP. For countries like Seychelles, Cape Verde, Rwanda, Morocco, Tunisia, but even for a larger country like Egypt. It employs over a million people in countries such as Nigeria, Ethiopia, and South Africa. So clearly tourism will suffer and that’s also going to be an important channel. And then there’s a couple of other channels that would also be very consequential.

The first is the sentiment channel, and early surveys have already shown both consumer and business confidence has dropped a lot in many countries. But also, importantly, the tighter financing conditions. Because COVID triggered this risk of sentiment that was followed by investor pullback from risky assets. And by some estimates, I think 100 billion dollars or more have already been pulled out of emerging market and developing countries, which is much higher than what we’ve seen during the global financial crisis. So consequently, for African sovereign debt, we’ve seen spikes in spreads and the yields have also skyrocketed from single digits now to the double digits. So those are limiting the possibilities to mobilize resources to fight the pandemic. And it’s going to have a significant consequence for the countries where I think now we expect them to have their worst economic performance in almost 30 years. Some estimated 150 million jobs are at the risk of being lost or seeing reduced income. And you’re talking about a region here that was already struggling to create enough jobs to keep up with the burgeoning youth population entering the labor market every year.

DOLLAR: So that’s obviously an enormous set of challenges. Thank you for that summary. Listening to what you were saying about remittances, it strikes me that there’s a very important ethical issue here because a lot of migrants have gone to advanced economies to contribute to the labor force and the production, and they should be covered by the safety nets in these countries which are generally pretty good. And that will enable them to continue to send some remittances back home. Alternatively, if they’re pushed out of these economies, that’s going to be quite disastrous.

COULIBALY: Yes, absolutely. One hundred percent agree.

DOLLAR: And then you raise the financial issues. That’s the next topic I wanted to take up. It was heartening that the G-20 quickly came up with this, I guess you’d call it a pledge, to have a debt payment moratorium for the low-income countries till the end of the year. And you’ve written that this is a good first step, but quite limited. So can you explain exactly what’s involved in that moratorium and how it needs to be expanded?

COULIBALY: Yes, indeed. I think the G-20’s action was really indeed a very important first step in terms of trying to free up some resources for these countries to fight the pandemic. And they are to be commended, really, for showing much needed leadership on this issue. It is consistent with an earlier call that some of us had issued, including the four special envoys of the African Union, calling for a standstill on debt repayments for two years. As I noted earlier, the economic impact is projected to be very significant, but sources of revenues have dropped, right. From export revenues, to tax revenues, to remittances . So accordingly, African countries have only been able to announce very small fiscal packages around less than 1 percent. And in some cases, it’s even less than one tenth of 1 percent. So by comparison, advanced economies did around 10 percent of GDP in some cases. So the standstill would create the much needed immediate fiscal space for those countries to provide meaningful relief and prepare their economies really for a solid recovery.

We wrote that it’s only the first step because it needs to be scaled up and broadened because the G-20 did not go as far as we thought was necessary to achieve the objective. The immediate resources gap estimated by the African finance ministers is 100 billion dollars, and according to the African Union, this estimate will rise to 200 billion by next year. So in that regard, the G20 action has fallen short. Moreover, the moratorium does not include all countries. Notably, countries classified as IBRD or middle-income countries were excluded because they have a presumed ability to mobilize resources through other channels, notably financial markets. But the reality is that, as I mentioned earlier, market turns are very unfavorable in this fiscal environment. Yet, some of these countries are the ones, as you mentioned or alluded to, have the highest cases of COVID. Egypt, for example, or South Africa. So unless they succeed in combating the pandemic, success in any neighboring countries would only be short lived.

So my own firmly held belief is that when it comes to really helping countries deal with the pandemic, the overriding criteria should be the resources gap to fight the virus. Past guidelines or approaches should not stand in the way of the appropriate policy action. So for this reason, I think the G-20 should broaden the scope of countries that are covered by the standstill and also support initiatives to mobilize fresh resources at a scale that is both commensurate with the challenge that the low income countries face but that is also in line with actions taken in the advanced economies. We had suggested a duration of two years for the standstill, which is what we thought was most appropriate, but the G-20 granted to the end of this year. But it did leave the door open for a possible expansion into 2021, which is a good thing.

DOLLAR: I noticed the prime minister of Ethiopia had an op-ed raising this issue and he had some very moving figures that Ethiopia is scheduled to spend more on debt repayments for external debt than it spends on public health in total.

COULIBALY: Yeah, absolutely. And I think for the continent as a whole, for several countries, this is over 20 percent of their government’s revenues. And even for some countries like Nigeria that still have relatively low debt to GDP level of about 30 percent.

DOLLAR: So assuming we do get some debt relief, obviously already we’re talking at least a first step, and as you say, the door is open for expanding that in time and in scope. Normally those kind of debt standstills or rescheduling would go hand in hand with IMF financial programs. And I know that dozens of countries on the continent have asked for IMF programs. So I wonder about your sense, does the IMF have enough resources, does it have the human resources to deal with this crisis?

COULIBALY: Well, I think you’re correct. So the traditional approach to tie the relief to the IMF program was also stipulated even in the G-20’s actions. And also, the countries have to be current on their debt service payments, both to the IMF and also to the World Bank. Now on the resources for the IMF to address this crisis, I would note that it’s not just about the IMF; there is also the World Bank and also Regional Development Bank and other development institutions and predators. But indeed, you’re right, the IMF is really central to this global effort. And the IMF have seen, indeed, a huge surge in the demand for assistance – over 100 countries, many of them are Africans. And I think the high uptake of this program can attest to the large resource gaps that these countries have. And I think the IMF has responded in deploying its entire lending capacity, which it estimates up to one trillion dollars. I know it has doubled its capacity for its emergency facilities, but it’s also replenished some trust funds such as the catastrophe, containment, and relief trust. And many African countries have already benefited from this from these programs.

But the question is always going to be one of scale. Is this enough and is it coming quickly enough to be able to provide the meaningful relief? And one area where many thought the IMF could have done more would have been on the creation of SDRs like it did during the global financial crisis. Many experts have even suggesting the figure of 500 billion dollars in SDRs to allow the countries to respond to the crisis in a meaningful way. Obviously, that proposal has not received the needed support among the G-20. And as you know, these types of initiatives would require IMF management to secure an 85 percent supermajority which is not easy even in a time when the global governance system is working well in singing one song. But these days, it’s not the case. So getting that supermajority was a tall order. But my reading through conversations with various stakeholders is that the political will to do so is not there, at least not at this stage. So this is it clearly an instrument that could have provided the resources at the scale that is needed. And my view is that it should really be exported further and it should be deployed because incrementalism or hesitation in policy response can only lead to an outcome that would be costlier to address down the road. So to paraphrase Mario Draghi, the international community, G-20, should really do whatever it takes.

DOLLAR: You know, I think that’s a great analogy. I mean, the IMF creating more SDR is very analogous to central banks creating money, which obviously Europe, the United States, Japan, China, all the central banks are dramatically expanding their balance sheets. And I think we should be frank. I mean, you mentioned you need an 85 percent supermajority in the IMF to issue new SDR. The U.S. share, I think, is right around 17 percent, so the U.S. has veto power. And if there were new SDR they would be allocated, to some extent, in proportion to the current global economic weights meaning China would get a larger share than its had in the past and probably India and some other countries. So you’ve got the existing powers, led by the United States, are reluctant to expand the SDR because it would be giving more influence to China, India, and other countries. So like you, I’m disappointed that they couldn’t resolve that bottleneck.

COULIBALY: And one other country that you didn’t a list would have been Iran, which is under sanctions.

DOLLAR: Yeah. So that’s a good lead into the next topic I wanted to raise. China has become a really important player in Africa, so when we talk about African debts, quite a bit of that has been lent by China to African governments for primarily infrastructure development. So on the one, it was heartening, that G-20 call for a debt moratorium that may be only a partial first step, but it was great to get 20 big economies that are both developed economies like the U.S. and the emerging economies like China and India to sign on to that. So I think that was quite positive. But obviously the Chinese lending goes well beyond these low income countries that are effected. There’s a lot of Chinese lending to middle income countries and Chinese lending from commercial banks to enterprises in Africa that doesn’t have a sovereign guarantee so it won’t be covered. So I guess my my question is, is this crisis going to create a rift between China and Africa because China is one of the big creditors and African countries are clamoring for much needed financial help?

COULIBALY: I certainly hope it doesn’t create the rift between China and Africa, but there is some some risk. And it’s not just about the debt issues, but also perhaps in how some African migrants in China were beaten and mistreated. And that actually sparked a widespread resentment coming from their continent to condemn those elections.

But I think it is the preference of African countries that the relationship does not deteriorate because, as we know, China has emerged as an important partner for Africa over the past two decades. Commercial, diplomatic, and defense ties have all strengthened over that period to the benefit, I would say, of both China and African countries which is why it would have been a severe blow to China-Africa relations if China did not lend its full support and voice to the global initiative for the debt standstill. And I agree with you that given this environment we are in to get the 20 countries, major countries, to agree on action I think was indeed an achievement. And China’s participation is really key to this success because it is the largest single official of bilateral creditor. So if it doesn’t participate or it wasn’t participating, then given the math itself it wouldn’t add up. It was good to see that, but it would also be good for China to even step up more in terms of lending its voice and support to the call to go further and extend the debt relief to middle income countries as well as extend the timeline of the moratorium which where some of the shortcomings we touched on earlier.

DOLLAR: We’ve had previous rounds of debt relief, and I think one thing that strikes me is it used to be a much smaller number of players. So you had a small number of official creditors, you know, major governments from the West and World Bank, IMF, et cetera. Now, there just seem to be many more players, and a lot of the debt taken on by African countries is essentially from the private sector; either bonds that have been floated or commercial bank loans, including commercial bank loans from China. They go to African entities without any kind of sovereign guarantee. So I’m a little bit worried that this is going to become a complicated issue because it’s hard to have debt relief on the official financial side if you’re not having some kind of debt rescheduling or relief on the private sector side.

COULIBALY: I think you’re exactly right. And even before this COVID episode, we had been, at the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings, following the debt situation very closely. And one of the clear observations of how the debt has evolved over the past two decades in Africa has been that now you have a more diffused creditor base. That in itself we thought was a good thing because it provides the countries with different options and it also attests to Africa’s economic prospects to have made a creditors willing to engage with you. But one risk that came with that as we also pointed out in the past, is that debt workouts would now become a bit more complicated. And as you correctly point out, it’s not the times when much of it was concentrated, say, with the Paris Club, et cetera, so that the workouts were made a bit easier.

Coming now to this COVID and how do we provide meaningful relief that can include private sector participation? I think it’s a very important question that many of us are wrestling with, and the issue is not really whether the private lenders should participate because the G-20 clearly called on them to do so, but it is on how they can participate in a way that still preserves the sovereign credit ratings of these African countries and their access to global markets in the future. As you know, many of them gained access for the first time over the past decade or so, and it’s been a very welcome and inevitable step in the countries’ economic development that has helped diversify their sources of funding.

But the private sector debt is also costlier. The debt servicing for many countries now exceeds 20 percent, as I mentioned earlier, of government revenues, and even for a country like Nigeria where the debt to GDP ratio is even lower around than 30 percent. And this is largely because of that commercial debt. So from that standpoint, the participation of private sector would be important. The key challenge is how to secure that without triggering a sovereign credit event such as a default. And one innovative approach might be to explore the creation of a special purpose vehicle that is adequately capitalized and that can issue, say, for example, special bonds in exchange for the existing ones or other obligations coming due this year or next year. I think if this works out, I think it would be a very viable option.

I want to take this opportunity to also clarify that the African countries are not asking for debt cancelation at this stage. They’re not asking for debt forgiveness like we’ve seen in the late-90s or early-2000s. They certainly appreciate their relationship with all creditors that stood with them when they needed their capital to finance development agendas, but the debt standstill that they are asking for is only to be able to fight the crisis that is unprecedented and that wasn’t really driven by mismanagement but an exogenous global shock. And it would come with an understanding that any arrangement would be a net present value neutral, meaning that the creditors would be made whole in the end.

DOLLAR: Let’s end on a positive note. Last question, so if you’re looking ahead about two years or so, what’s the positive scenario for African countries in response to this global crisis?

COULIBALY: I think the positive scenario would be that indeed the number of cases that you started out by observing that they relatively low for Africa, that they do indeed reflect the reality on the ground, and that there are some other factors that make the African countries resist better or recover faster from this COVID virus. In that case, then, I could foresee a scenario where the economies are able to recover much faster, the human casualties a bit more limited, and by then hopefully the advanced economies have made a lot of progress in their own recoveries and that we’ve seen some good signs that a vaccine is forthcoming. That improvement takes on a new environment, as well as the limited casualties within Africa itself would have created the kind of environment that would really boost the economic recovery much faster than is currently being projected.

DOLLAR: So I’m David Dollar, and I’ve been talking to Brahima Coulibaly, director of the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings. We’ve been talking about how the public health crisis and the economic downturn are affecting African economies, and he’s given us some really good ideas about how things can be improved. So thank you very much for joining our show.

COULIBALY: Thank you for having me.

Commentary

PodcastHow to ensure Africa has the financial resources to address COVID-19

May 4, 2020