On January 21st, the Supreme Court decided not to grant expedited review of a lower court ruling that would invalidate the entire Affordable Care Act (aka ACA or Obamacare). For reasons to be set forth presently, the lower court decision is absurd, and the Supreme Court decision not to take the case now will extend for at least a year uncertainty over the future of the Affordable Care Act. This uncertainty imposes real costs on millions of Americans, health care providers, and state governments. It also spares the Trump administration from being put in an awkward position on health policy in the midst of the 2020 presidential election.

The case revolves around the ACA provision that required people to carry health insurance. When the ACA was being debated, advocates argued that a requirement that people carry health insurance was necessary to back up another highly popular provision—that insurers must sell insurance to anyone who wants to buy it and do so at a price that does not vary with the health of the buyer. Without the mandate, ACA advocates feared, many people might not buy coverage until they became sick. If that happened, insurers would have to set premiums so high that that few people would want coverage, causing insurance markets to implode. So, invoking its power to regulate interstate commerce, Congress mandated that people who could afford it must carry approved insurance. And in ‘belt-and-suspenders’ manner, it also imposed a tax on people who failed to do so.

Critics of the law believed that the ‘individual mandate’ went beyond the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce. In 2013 the Supreme Court agreed, ruling that the Commerce clause did not authorize Congress to tell people what they had to buy, but the Court also ruled that the tax on people who did not carry approved insurance was constitutionally permissible. As the tax was the enforcement mechanism, the mandate remained in effect.

Four years later as part of the 2017 tax bill, however, Congress cut the penalty tax rate to zero. With the enforcement mechanism reduced to nothing, the mandate was dead…people could do as they wished.

At this point, eighteen states, led by Texas, claimed that by zeroing out the tax, Congress had rendered the whole ACA unconstitutional. This may sound like an enormous stretch, but here is the argument: The Supreme Court had declared the mandate went beyond Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce. After the tax that enforced the mandate was cut to zero, all that was left was a legal provision that was not justified by the Constitution. If the coverage mandate was necessary to make the insurance regulations work, as ACA advocates had argued, but the unconstitutional mandate was backed up by a meaningless zero tax, then, the Texas group argued, the insurance regulations had to be declared unconstitutional too. So too did the rest of the ACA because Congress had failed to include in the law a so-called ‘severability’ clause stipulating that even if some provisions were declared unconstitutional, the rest of the law should survive.

Let’s stop here and take note of how wacky this argument really is, a view shared by supporters and critics of the ACA alike. A toothless coverage mandate can harm no one, directly or indirectly. But a showing of harm is ordinarily necessary for a plaintiff to establish standing to sue. So, the absence of harm should have caused the case to be dismissed. In addition, and contrary to the fears of ACA supporters, insurance sales barely changed after the penalty tax was eliminated, and premiums, which had been rising rapidly while the mandate was in effect, stabilized. So, contrary to the arguments that ACA advocates had advanced, the mandate was not needed to back up the insurance provisions. And since Congress could have, but did not, repeal or otherwise modify the ACA when it zeroed out the tax on those who fail to buy insurance, no severability clause was necessary to show that Congress intended the ACA to survive if the mandate was invalidated.

Despite the flabby logic behind this case, a federal district court judge ruled the ACA unconstitutional, and two of three appellate court judges agreed—in general. The appellate judges did, however, defer enforcement of the decision until the trial court judge did something that one might have thought he would have done in the first place—explain which provisions of the ACA should be declared unconstitutional and why.

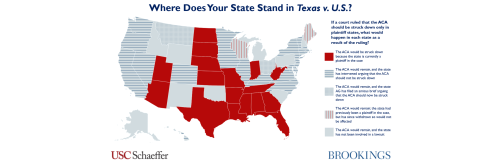

At this point, officials in twenty-one other states and the House of Representatives entered the fray and asked the Supreme Court to rule before further lower-court litigation was complete. They reasoned that the lower court decision is virtually certain to be reversed at some point and that delay is costly. Business investment, state budget planning, and individual security remain under threat. Ending the ACA’s extension of Medicaid coverage to millions would throw state budgets into turmoil.

On January 21 the Supreme Court refused this appeal for a quick decision.

A heavy smell of politics surrounds this litigation. The plaintiffs seeking to invalidate the ACA in this case were all from states whose elected officials opposed the ACA. Although the Justice Department customarily defends federal legislation when it is challenged in federal courts, the Trump administration refused to defend the ACA during appeal from the lower court decision. Those asking for an immediate ruling by the Supreme Court were all from states whose elected officials support the ACA. The trial court judge is a former Republican staffer on Capitol Hill. He and the two appellate judges who voted to sustain his ruling were appointed by Republican presidents.

Although the decision by the Supreme Court to prolong litigation in the lower courts poorly serves the nation, it does offer a temporary safe-harbor to the Trump administration, as any decision before the election would have been problematic. Had the Supreme Court tossed out the lower court decision before the presidential election, it would have advertised the failure of an effort, supported by the Trump administration, to undo perhaps the largest achievement of the Obama administration. Had the Supreme Court sustained the lower court, it would have stripped health insurance coverage from as many as 30 million people smack in the middle of the presidential campaign. Trump administration officials must have breathed large sighs of relief when the Supreme Court punted its decision to 2021.

Commentary

Op-edThe Supreme Court procrastinates: No decision now on a baseless challenge to the Affordable Care Act

February 10, 2020