Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

This piece was originally published in Footnote, and is reprinted with permission from the publisher. Read the piece on Footnote.

The ongoing peace talks between Israel and the Palestinians were rough from the beginning, with constant media reports on spats between the two sides. Be that as it may, it goes largely unmentioned that Hamas, the second major Palestinian political entity, has not been part of these negotiations. I argue that this is both a mistake and a missed opportunity, especially because of the largely unnoticed shift in Hamas’ ideology.

In recent years, the movement went from holding a religious ideology to becoming a nationalist movement focusing on national rights. In this article, I highlight this crucial transformation on the Palestinian scene, discuss this shift in Hamas’ ideology in the period from 2005 to 2012, and explore the implications of this transformation regarding the prospects for peace.

Hamas has become a main Palestinian actor when it won the democratic Palestinian legislative elections in 2006. Despite attempts by Palestinian and international actors to push Hamas back to the sidelines through financial pressures and military interventions, Hamas remains an actor that dominates the Palestinian scene. Both before and after 2006, Hamas has changed considerably in ways that inevitably bear on the political choices and positions that the movement may adopt regarding peace talks. These changes, however, have been completely ignored by the international community, Israel and some regional actors, who continue to view Hamas through a 15 years old lens: as a violent, Islamist and terrorist organization. Contrary to this commonly held view, for example, high-ranking members of Hamas have asserted that Hamas is a constantly changing and self-transforming movement.1 The very fact that the movement survived for more than 25 years affirms this: any political actor needs a degree of pragmatism and flexibility to survive the ever dynamic politics of the Middle East.

For my doctoral research in peace and conflict studies, I analyzed the discourse of Hamas in its daily Arabic communiqués addressed to its members and supporters between 2005-2012, based on selected events for each year and for two months after the selected event. I was interested in exploring how a movement like Hamas justifies violence in its discourse and how it legitimizes its political choices. The analysis revealed many interesting results, a few of which I share below.

The communiqués are published by the Hamas Media Office and are available on the Hamas affiliated website. Hamas’ daily communiqués contain messages that Hamas addresses to its local audience, members, and supporters. The addition of languages like Turkish, Bahasa, Urdu, English, and French is very recent.

One major area of shift in Hamas political ideology that emerged from my research is the shift from religious ideology to nationalism. In this, Hamas seems to be a part of a broader trend of mainstream Islamic parties that sooner or later have to come to terms with the fact that an all-inclusive umma-based ideology is not practical in today’s political scene. The most prominent current example of such thinking is El Nahda in Tunisia, which talks about “Tunisian Islam” rather than Islam. In contrast, however, this shift in Hamas was not influenced by the “Arab Spring”. Hamas’ transformation started back in 2005, when it decided to participate in Palestinian elections.2 Authors like McGough and Abu Namil refer to hints of this transformation in earlier years as well, like the shift to hudna and the decline of use of the word Jihad. But they do not provide a systematic analysis to prove these changes.3

In what follows, I detail the shift towards nationalism through three linguistic changes in Hamas’ communiqués: from umma to sha’b, from Jews and Judaism to Israelis and Israel, and from jihad to resistance.

Umma vs Sha’b

The term “umma” refers the Muslim community that transcends national and/or ethnic affiliation. It is an all-encompassing bond. By contrast, the term “sha’b” indicates the national community based on national affiliation.4 The shift towards sha’b in Hamas’ discourse is crucial. Hamas commits itself to Palestinian national goals, not a universal Islamic ideology like that of Hizb ul-Tahrir that seeks to revive the Islamic Caliphate. A quantitative analysis drives this point home. For example, the words “sha’b” and “our sha’b” were used 282 times in selected communiqués in 2006; but the words “umma” and “our umma” were used only 40 times in the same sample. In 2012, the totals are 77 for “sha’b” and “our sha’b” and only 5 times for “umma” and “our umma.”

A qualitative analysis also confirms this prominence. For example, Hamas usually refers to its unchanging principles and political positions as “constants.” In the section on “constants” in the 2005 elections platform, Hamas includes “the complete adherence to the constant rights of our sha’b in the land, Jerusalem, the holy sites, water, borders, and the Palestinian State with Jerusalem as its capital.” The platform also states, “Historical Palestine is part of the Arab and Islamic land, and it is a constant right for the Palestinian sha‘b despite lapse of time…” Both the issue of Jerusalem and the conflict over ownership of historic Palestine remain among the unchanging positions of Hamas. Yet, Hamas claims these rights within the frame of the national rights of Palestinians rather than the religious rights of all Muslims. Given the significance of Jerusalem for all Muslims, it is intriguing that Hamas chose not to use the word “umma”, thereby explicitly asserting the nationalist over the Islamic.

Jews vs Israelis

In addition to the shift from “umma” to “sha’b,” there has been a similar nationalist shift in how the State of Israel is attacked and criticized. Hamas no longer identifies Israelis by their religion. The terms Jew, Jewish, or Judaism are not used in any communiqués. Earlier Hamas discourse, like that of its charter, written in 1988, and of earlier communiqués from 1990 or 1994, refers to Israelis as “Jews” or “the enemy” who is “Nazi” and “Zionist.”5

This does not mean that Hamas has stopped attacking Israel in its communiqués. Hamas continues to oppose Israel, but mainly due to the military occupation of Palestinian lands. The State of Israel is referred to as either “the occupation entity” or the “Zionist establishment” (mo’assasah), never as Israel. The intention seems to be to assert the relation of oppressor versus oppressed. Only one of the 277 analyzed communiqués refer to the state of Israel as such. But despite the fact that all terms used by Hamas are critical of Israel, they all place the conflict in nationalist frames. References to Zionism are prevalent in Hamas discourse, mainly because Zionism is understood by Hamas as an exclusivist nationalist ideology. Interestingly, these are exactly the wordings used by Israel to prove that Hamas wants to eliminate Israel. Yet, Hamas would not have indicated its acceptance, more than once, of a two-state solution, if its aim were indeed to eliminate Israel. And more importantly, there are different groups within Hamas with their different positions towards Israel.

Hamas’ earlier communiqués specifically attacked Jews and portrayed the conflict as one between Judaism and Islam. Today, Hamas draws clear lines between Jews and Judaism on the one hand, and Israeli state policies and Zionism as a nationalist ideology on the other. In the last 8 years, Hamas’ discourse reveals an indifference to Israel’s Jewish identity. Religious discourse is still used, however, to justify violent resistance as legitimate “jihad,” and to portray Hamas as a pious group.

Jihad vs Resistance

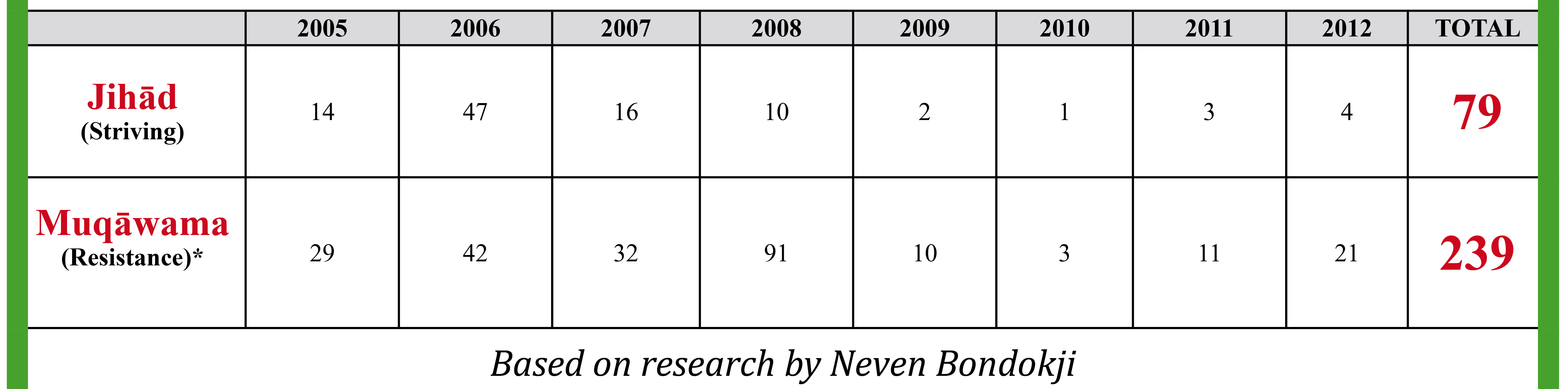

A similar linguistic shift in Hamas’ communiqués has been that from jihad to resistance. Earlier communiqués highlighted jihad, understood in Hamas’ discourse as violent resistance to Israeli military occupation, and as the individual religious duty of every Muslim.6 But the decline in the use of the term in Hamas’ discourse is so sharp that it cannot be ignored.

The table below highlights the sharp decline in the use of the religious term “jihad” and its replacement with the more nationalist and secular term “resistance.” Throughout the years, “resistance” has replaced “Jihad” to a significant degree. The only exception here is in 2006, when the communique sample was based around the June 25 kidnapping/imprisonment of the Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit and the ensuing violent confrontations between Hamas and Israel. Violent confrontations, however, took place in other periods as well and were not confined to that event. For example, although the analysed sample includes communiqués released just after the Gaza War (“Operation Cast Lead”) of December 2008, the use of the term “resistance” remained prominent, despite the fact that the context could have explained the prominence of a defensive “Jihad” in that period.

*This excludes the word resistance when it appears within the full name of HAMAS (the Islamic Resistance Movement).

Ground-breaking Announcements

These changes did not appear in a vacuum. These changes have been simultaneous with two major ground breaking statements from Hamas. The first was made in a speech by Khaled Mishal, Head of the Political Bureau of Hamas, in June 2009, in which he accepted a two state solution based on 1967 borders. Three years before that, Ismail Haniyyeh, then Hamas Prime Minister, made a similar announcement. In a rally in Gaza on October 6th, 2006, Haniyyeh announced that Hamas will accept establishing the Palestinian state within 1967 borders in exchange for a hudna, but not in exchange for recognition of the State of Israel.7 (Hudna is a long-term truce, which HAMAS has offered on more than one occasion. A hudna can be as long as 30 or 50 years.) The announcement, however, went almost completely unnoticed, despite the fact that a hudna on these terms may very well be a possible interim solution in a time when all other options have failed.

These strategic shifts towards a nationalist approach –based on Palestinian national interests- are extremely risky for Hamas on the local level. Significantly, it seems that Hamas is willing to take the risk in order to secure a nationalist outcome, in other words to settle for part of the land rather than the whole area of historic Palestine.

Hamas is in many ways already paying the price for this choice. A large part of Hamas’ dwindling support in the Occupied Palestinian Territories today has to do with the perceived lack of commitment from Hamas to its violent resistance against Israel. For example, while Hamas committed to a one-sided truce in 2006, other factions pronounced their rejection of this truce by launching an armed campaign against Israeli targets.8 Its attempts to control such attacks by other groups in Gaza has caused Hamas heavy losses to its membership base. Around 3,500 of its Izzidine Qassam Brigade members left Hamas to join newer and more extremist groups in Gaza.9 Thus, these members and other more extremist actors in Gaza blame Hamas for giving up its violent resistance to Israeli occupation.10

Needless to say, the shift in Hamas’ position on a final status agreement, namely accepting part of the land within the framework of a two-state solution, is placing Hamas in a tight spot vis-à-vis other armed groups in Palestine who demand the full area of historic Palestine. Hamas’ acceptance of a two-state solution as a formal outcome or in the form of a long-term hudna both indicate that Hamas is ready to accept land and statehood in West Bank areas of the Occupied Palestinian Territories and give up larger claims over the area of historic Palestine.

Implications for the Prospects of Peace

The shift from religious ideology to nationalism is more groundbreaking than it may seem at first. This commitment to the nationalist agenda differs widely from the view of Hasan al Banna, founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, from which Hamas has emerged. Al Banna argued forcefully that Islamic solidarity precedes the national struggle.11 Ahmad Yasin, considered the founding father of Hamas, also argued that if commitment is made to land rather than religious doctrines, then that creates the threat of replacing one piece of land with another.12

This is exactly why the shift toward nationalism is important. A shift to nationalist agenda means a shift towards negotiated interests. Religious ideology, on the other hand, presents more non-negotiable values. This is not to say, however, that religion has been the obstacle to peace in the region.

Just like religion, nationalism is largely an exclusivist ideology that demands blood in its defense.13 What I am trying to clarify, however, is that religious ideology will focus on an all-encompassing and uncompromising demand for the whole area of historic Palestine, with affiliation to the larger Islamic umma, while a nationalist agenda will require a Palestinian statehood on part of historical Palestine with the support and affiliation of Palestinians, not all Arabs or all Muslims.

Because of this shift, one can speculate that negotiations with Hamas over interests rather than values could very well lead to a tangible outcome. By breaking with al Banna and Yasin and limiting its resistance to the geography of historical Palestine, Hamas is asserting the realm of nationalist interests as a priority over religious values.

Needless to say, the rapid changes in the region, the success of nonviolent campaigns in ousting dictators, the situation in Syria, and the political situation of Islamic parties in Tunisia and Egypt, have all given Hamas much to reflect on in terms of its political choices. The rise and fall of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, the more pragmatic and accommodating approach of El Nahda, the role of AKP in Turkey, all these present Hamas with models of Islamic parties in power. Hamas’ leadership now resides in Doha, where a crisis is unfolding between members of the Gulf Cooperation Council over the policies of individual countries towards the Muslim Brotherhood. Despite its ideological shifts, Hamas was and continues to be a loyal off-spring of the Muslim Brotherhood. How these shifts will affect the political choices of Hamas is yet to be seen. What is clear, though, is that, like in earlier years, Hamas will continue to change and transform itself. What is crucial, however, is understanding how these transformations can help in reaching a mutually-acceptable peace deal between all Palestinian actors, on the one side, and Israel, on the other.

Footnotes:

1. al-Julani, Aṭif, and Hamza Haymur. “Dialogue with Khalid Mishal: Our Vision is Clear.” (in Arabic). as-Sabīl Weekly (Amman), July 21, 2010.

2. The decision to participate in legislative elections in 2005 highlights a strategic acceptance to join the mainstream of Palestinian politics from within the framework of Oslo Accords. Hamas has continuously opposed and refused these accords.

3. McGeough, Paul. Kill Khalid: Mossad’s Failed Hit and the Rise of Hamas. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2009, p. 412; Abu Namil, Hussayn. “HAMAS from Opposition to Authority or from Ideology to Politics].” (in Arabic) In Critical Readings of HAMAS Experience and its Government, edited by Muḥsin Saliḥ, 24-33. Beirut: Markaz az-Zaytūna lid-Dirāsāt wal Istishārāt, 2007.

4. Ahmad Shboul, “Between Rhetoric and Reality: Islam and Politics in the Arab World,” in Islam in World Politics, eds. Nelly Lahoud and Anthony H. Johns (London and New York: Routledge, 2003), p. 171.

5. For example, in Articles 7, 20, and 32 of Hamas Charter; early communiqués are available in Media Office of HAMAS, Documents of the Islamic Resistance Movement. (in Arabic) 4 vols. (no city): HAMAS Media Office, (no date).

6. Article 15 of Hamas Charter.

7. For details on HAMAS’ propositions on hudna and other nonviolent options, see Scham, Paul, and Osama Abu-Irshaid. Hamas: Ideological Rigidity and Political Flexibility. Special Report 224. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace, June 2009; and Tamimi, Azzam. Hamas: Unwritten Chapters. London: Hurst & Co., 2007, p. 166-69.

8. Khaled Hroub, “Hamas after Shaykh Yasin and Rantisi,” Journal of Palestine Studies 33, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 25-26.

9. Sayigh, Yezid. Hamas Rule in Gaza: Three Years On. Middle East Brief (41). M.A.: Crown Center for Middle East Studies at Brandeis University, March 2010.

10. Abullah bin Bijad al-Utaybi, “HAMAS and Jihadi Salafism Face to Face,” al-Itihad (Abu Dhabi), August 24, 2009; and Muḥammad Abu Qamar, “The Story of the Emirate of Abdul Latif Musa,” (in Arabic) Filasṭīn al-Muslima no. 9 (Sept. 2009), p. 22-25.

11. al-Banna, Hasan. Collected Messages of the Mertyred Hasan al-Banna (in Arabic)

12. Abu Amr, Ziad. “Shaykh Ahmad Yasin and the Origins of Hamas.” In Spokesmen for the Despised: Fundamentalist Leaders of the Middle East, edited by R. Scott Appleby, 225-56. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997, p. 243-44.

13. Juergensmeyer, The New Cold War? Religious Nationalism Confronts the Secular State. Berkleley: University of California Press, 1993, p.15; Malise Ruthven, Funamentalism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 2007), p. 93.

Commentary

Op-edThe Nationalist versus the Religious: Implications for Peace with Hamas

March 18, 2014