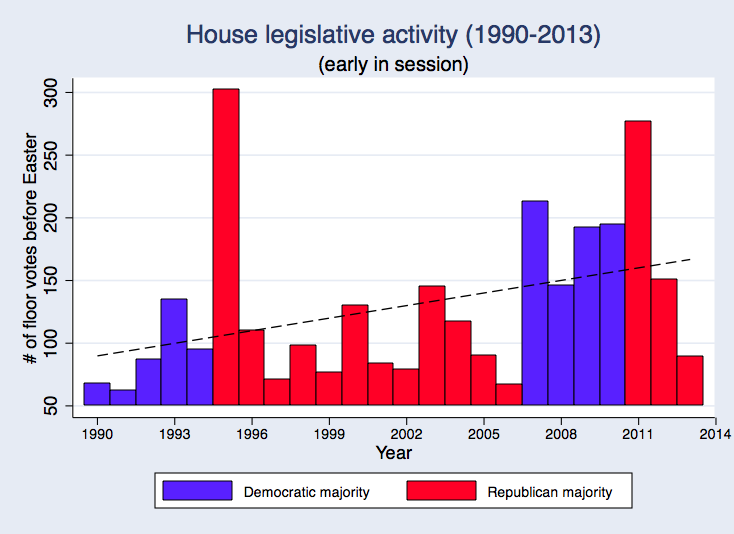

I noticed the other day that House lawmakers have cast relatively few recorded roll calls this year—voting just 89 times before leaving town for spring break. To put those roll calls into perspective, I gathered two decades or so of House “early voting” data—the total number of votes cast each year between the start of the session in January and the last day of voting before Easter. Granted, Easter jumps around the calendar like a (Peeps) bunny. But party leaders do target their floor agendas to approaching recesses, so it’s reasonable to use the Easter break (rather than a fixed calendar date) to mark the end of each session’s “early voting” period. With that caveat in mind, some brief thoughts on recent patterns in early voting

For starters, some notable patterns appear in the data. The 113th Congress is indeed off to a slow start—showing the least amount of roll call activity since 2006. More generally, the drop in House roll call voting runs counter to a broader trend of ever expanding legislative floor voting. Regardless of whether Democrats or Republicans hold the gavel, the House has increased its workload each winter over the past quarter century. That said, bursts in legislative voting take place only after a changing of the guard to a new majority. In 1995, 2007, and 2011, roll call voting jumped precipitously: New chamber majorities appear to follow through on their electoral promises to change the agenda in Washington, whether it’s Newt Gingrich’s Contract with America or Nancy Pelosi’s Six for ‘06. Coupled with new majorities’ frequent campaign promises to broaden participation on the chamber floor, such commitments likely drive the surge in legislative activity when party control changes hands.

Before going too far here, rest assured that I recognize the limitations of such data. We can’t judge a Congress’s broader performance by its winter legislative season. Moreover, we might want to distinguish between first and second session winter voting records. (The former might be interesting; the latter, not so much.) In any case, output measures such as votes are better viewed in comparison to the array of demands faced by legislators. We want to know what Congress accomplished, relative to the big issues and problems of the day. In short, more roll calls do not necessarily mean a better legislature. Still, I think the relatively low level of House legislative activity at the start of the 113th Congress is worth pondering.

This year’s quiescent House floor likely reflects a few developments.

First, the steep drop off in early voting partially reflects Congress’s recent difficulty in making fiscal policy. The GOP’s willingness in 2011 to open up the appropriations process to nearly unlimited amendments by both Democrats and Republicans helped to drive up the number of early roll calls. This year, GOP leaders were unwilling to allow any rank and file members to take a crack at the mammoth CR: Opening up the bill to amendments would have threatened a carefully knit package of limited changes to the CR. Given bipartisan concerns about the impact of the sequester, allowing amendments could have derailed the bill before its must-pass deadline. Tentative majorities prefer limited legislative activity.

Second, welcome to the “Boehner Rule” House. By definition, the GOP leadership’s new practice of letting the Senate go first drives down early House floor activity. Boehner’s reluctance to have the House go first reflects the difficulty of cobbling a chamber majority without Democratic votes: The GOP’s thin margin and the threat of defection by rank and file GOP on measures deemed insufficiently conservative could keep House floor activity depressed for awhile. (Witness the sixteen GOP who voted against bringing the CR to the floor and the eight GOP who have voted “no” on each critical vote this year.)

Third, and related, letting the Senate go first may offer political dividends to the House leadership. The Senate might no longer be the world’s greatest deliberative body, but it’s still the most sluggish. The House leadership likely benefits from legislative delay, particularly on the big issues of the day that create electoral dilemmas for the GOP’s brand name (for starters, immigration reform and gun control). Delay offers opponents time to mobilize, allows public support to wane, and lets House Republicans blame Senate Democrats for congressional inaction. Win, win, win (at least for now) for a party leadership unable or reluctant to build a legislative majority for reform.

In short, these data are limited but potentially revealing. House leaders no doubt are using the time to devise and sell a legislative strategy going forward. Given the difficulties of squaring the party’s ideological and electoral ambitions with the demands of its rank and file, no surprise House leaders (men and women alike) have avoided leaning in.

Commentary

Op-edThe Do-little House of Representatives: Why so Little legislating?

April 4, 2013