The following essay comes from “Meaningful education in times of uncertainty,” a collection of essays from the Center for Universal Education and top thought leaders in the fields of learning, innovation, and technology.

William Gibson, the lauded science fiction novelist, is credited with the saying: “The future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed yet.”

William Gibson, the lauded science fiction novelist, is credited with the saying: “The future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed yet.”

Like far too many other profound and attributed quotes, no one seems to be able to pin down whether Gibson actually said it. But, whatever the source, these are important words to keep in mind as we search for meaningful education in uncertain times. Armed with neurological research, innovative educational practice, and high-tech wizardry, a key risk is we design an educational approach of huge sophistication that creates a new future for some while many millions are left behind.

Locking in that educational unfairness would then cause a cascade of other inequalities. Already some 40 percent of employers globally are finding it difficult to recruit people with the skills they need. If education in much of the world fails to keep up with the changing demand for skills, if it remains behind 21st century standards, then there will be a major shortage of skilled workers in both developing and developed economies, as well as large surpluses of workers with poor skills.

This mismatch between the demand for skilled labor and its supply will lead to growing inequity. Indeed, the growing skills gap will prevent the world from reaching the most fundamental of all development goals: Ending extreme poverty.

Avoiding that future requires working out how to deliver meaningful 21st century education at scale in some of the poorest parts of the world. It can only be done if whole education systems are dramatically improved.

Fortunately, the world is not starting from scratch in addressing this challenge. One example, from Ghana, helps paint the picture of what is already underway. In 2012, the Government of Ghana unveiled its Education Strategic Plan (ESP), a 10-year blueprint of how the country aimed to educate its citizens.

Brimming with data, statistics, and technical language, Ghana’s two-volume ESP is based on in-depth analysis of the country’s education landscape and best practices from similar environments around the world. It spells out in detail how the country would get more of its children to go to school and learn. Among other goals, the plan calls for narrowing the gap between the number of girls and boys who receive and complete their schooling, enabling more children to transition from primary to lower secondary school, improving the quality of teaching and learning materials, and professionalizing the management and delivery of education.

Ghana’s latest ESP stands on the shoulders of four previous plans, which have produced, especially over the last two decades, impressive results: Dramatic increases in school enrollment at the primary and secondary levels—among girls and boys—and in the proportion of those who complete school.

Much of that progress is a direct consequence of the Ghanaian government’s strong commitments to education and the steady increase of its investment in education. The government’s devotion to planning, monitoring, and delivering of basic education services—especially in economically deprived districts across the country—is fundamental to the progress the country continues to make.

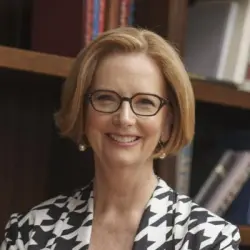

Ghana’s success is also based on support from external partners, notably GPE, the Global Partnership for Education (whose board I chair), which has provided the country with $94.5 million in funding since 2005. GPE has been instrumental in helping Ghana strengthen its education system with a strong focus on equity. Indeed, only strong education systems can ensure the most disadvantaged children are able to complete their education.

System strength matters

It would be easy—but misleading—to conclude that the substantial domestic and external funding over the last decade and a half has made all the difference in Ghana’s educational progress. No doubt, funding is essential, and countries like Ghana will need more of it if we are to come close to the Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring an inclusive and quality education for all the world’s children by 2030. But money is only part of the equation.

Of equal importance is how well each country creates and implements a comprehensive education system that reaches all its children and which will endure for generations to come. That is why those of us who work every day on global education have to focus on the importance of systems. Learning improves when countries like Ghana commit to building education systems over the long term.

In fact, according to an analysis by the International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity (or the Education Commission), on which I serve, countries with better education systems—even some with relatively small pools of money to spend—achieve better learning outcomes than others with less effective systems. The Education Commission’s review of data compiled by the World Bank’s SABER initiative (or Systems Approach for Better Education Results) showed that a strong education system in a middle-income country can produce results as good as those in higher-income countries with weaker education systems.

Even poor countries, the Education Commission found, can produce students who perform as well as students in high-income countries. Vietnam, for example, spends about the same amount per pupil on education as Tunisia, as a percentage of per capita GDP. The Commission notes that in Tunisia only 64 percent of students passed the secondary international learning assessment, while in Vietnam 96 percent did.

Not coincidentally, the Government of Vietnam has been tenacious about creating a strong, well-functioning education system. Since 2008, Vietnam not only spent 20 percent of its own domestic budget on education, it has also produced and implemented strategic plans that commit to consistent, long-term education strategies, expanding high-quality, universal education and teacher-training programs, and conducting relevant research.

The Education Commission also notes that educational performance disparities within countries often arise because education systems in some regions are stronger than others. In Pakistan, for example, the districts of Gujranwala, Bahawalpur, and Khanewal spend approximately the same level of funding per child, but learning outcomes across the three districts differ widely.

Elements of a good system

Good education systems are made up of a range of elements, including, for example, those that guide development (political and civic leaders); analyze data about progress (information analysis); deliver knowledge and sustenance (school administrators, teachers, books, and curricular materials); constantly seek ways to improve (innovations); ensure everyone is served (inclusion and equity); and keep it nourished (with financing and other resources).

Systems approaches are important because they ensure that the delivery of quality education is equitable and consistent throughout a country and across many different regions, cultures, and income levels. It requires aligning contributions from thousands of teachers, school leaders, communities, and other service providers. If children have classrooms but no books, or teachers with a poor curriculum, their opportunities to learn are weakened. A systems approach focuses on getting the right resources to the right places with the right combination—and making sure, in particular, that those services reach the most disadvantaged and marginalized.

In other words, the strength of any education system depends not only on how well a country executes each of these attributes individually but also on the extent to which it manages the interplay among them paying very close attention to equity. Like any good orchestra conductor, governments must get a diverse collection of instruments, each playing its own notes, to produce a sound of coherent splendor.

GPE’s support for systems

Strengthening education systems matters, and that’s why it is at the heart of GPE’s approach, which includes three main components:

First, sector planning. GPE is the single largest international funder of education sector analysis and planning processes. It provides countries up to $500,000 to look closely and analytically at what is happening—or not happening—in their education sector and come up with detailed plans based on that information.

Each plan is unique because each country’s educational challenges and opportunities are unique. But, through GPE, countries have access to a range of policies and initiatives that have been proven or show promise in similar settings around the world. Education plans operate as “cases for investment,” around which countries can raise additional financing to scale programs.

Second, mutual accountability and inclusive policy dialogue. GPE requires governments and their partners to convene multi-stakeholder local education groups, enabling all relevant players in a country’s education community to contribute throughout the policymaking cycle—from analysis to planning, and to the monitoring of plan implementation.

GPE also encourages governments to conduct an annual joint review of national education progress. Indeed, GPE is the largest funder of national civil society coalitions, which provide essential oversight of service delivery, through budget and policy tracking. GPE also invests in improving the capacity of teachers’ organizations to play stronger roles as advocates and problem solvers that can achieve quality education outcomes.

Third, results-focused implementation financing. GPE not only funds education planning, but also the implementation of those plans. GPE grants incentivize countries to focus efforts to drive results, offering one-third of each grant allocation for improvements in equity, learning, and efficiency.

GPE also requires governments to make increased investments from their own domestic funding—ideally, 20 percent of the national education budget (with significant concentration on basic education)—and improve data systems for better monitoring and accountability. And GPE allocations target low- and lower middle-income countries with high numbers of out-of-school children at primary and lower secondary levels. More than half of GPE grants flow to countries affected by fragility and conflict.

In Ghana, a key element of GPE’s support was to empower districts and schools to plan and prioritize their needs—a core element of a strong system. Knowing what is needed at the central level can lead to more regular, predictable levels of funding for districts, which in turn ensures consistently good teaching that will drive better learning. Grants from GPE also deepen community and stakeholder engagement in school management, which enhances the accountability of systems, and improves school leadership and record keeping.

No discussion about the importance of education systems would be complete without an acknowledgment that building and sustaining a good system requires patience and persistence. Ghana’s decades-long planning, for example, has put educational performance on a steady upward path. But challenges remain. A portion of Ghana’s children remain difficult to enroll in school. The country still faces poor learning outcomes in early grades and inequities when it comes to getting students in school. However, it has made progress in recent years in stemming a higher-than-acceptable rate of teacher absences in some areas.

Still, because it has made the effort to understand and respond to its changing educational landscape, Ghana—like so many other countries that have committed to building strong education systems—is in a far more fortunate position to succeed.

Providing the best of educational thought and adequate resources to this kind of systems strengthening is the only way of ensuring a shared 21st century future.

Commentary

Op-edSharing the future by building better education systems

August 3, 2017