Clinicians and hospitals across the nation struggle with providing and paying for optimal care for their congestive health failure (CHF) patients. However, there are opportunities to make care better. In fact, of the more than 10,000 pages in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) implementing regulations, the least talked about are the dozens of small experiments led by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) that test new ways to pay for medical services.

We use a case study approach to investigate and tell the story of what two academic medical centers, Duke University Health System (“Duke”) and University of Colorado Hospital (“Colorado”), are doing to innovate and improve CHF care while implementing alternative payment models offered by CMMI.

The Clinical Scenario: A Chronic, Disabling Illness

Robert Neelley Church had chest pains, persistent shortness of breath, and fluid buildup that caused extreme discomfort even during mild exertion, such as bending over to tie his shoes. After a visit with his primary care physician and cardiologist, Robert, an 86-year old Tennessee resident, learned his aortic valve (which helps the heart pump blood to the body) was not working efficiently and that he had congestive heart failure (CHF). Robert is one of the nearly 6 million Americans affected by this chronic condition, is the leading cause of hospitalization among adults over the age of 65, and well known for disproportionately affecting African American and Hispanic populations.

The Challenge: Moving Beyond Volume-Based Care

The high costs related to CHF (a staggering 17 percent of overall national health expenditures, $273 billion in direct medical costs, and $172 billion in indirect costs), like the costs associated with many chronic diseases, are driven by a deeply fragmented and uncoordinated health care system. This often results in patients like Robert seeking care from the emergency room, suffering from avoidable complications, and being readmitted to the hospital. In fact, 24 percent of CHF patients are readmitted to a hospital within 30 days.

However, clinicians have strategies to improve care and reduce costs for CHF, and other chronic conditions. These strategies rely heavily on shifting from high-intensity, expensive inpatient care to preventing, coordinating, and managing the illness in outpatient or primary care settings. Most importantly, lasting changes in CHF care require alternative payment models that support proper disease management, care coordination, and other activities that are not currently reimbursed in a fee-for-service, volume-based payment system.

The Key Levers: Supporting Change With Alternative Payment Models

Today providers have the opportunity to test new payment models that, if proven effective, may be implemented nationwide. The Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative and the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) option for Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) represent two such opportunities.

The BPCI consolidates all services provided in a patient’s episode of care, rather than paying each provider separately for individual services or procedures. It incentivizes care coordination across 30-, 60-, or 90-day episodes and across multiple settings. The price is set by consolidating historical prices per episode and discounting them by 3 percent. An MSSP is a group of providers that is paid a global, fixed amount per patient; the ACO provides all necessary services and reports certain quality measures, and it shares in roughly half of the savings generated compared to certain historical spending targets. (This is so-called “upside” risk; ACOs can also choose to incur “downside risk” as well, sharing in 60 percent of savings but also taking on risk for the same percentage of losses.).

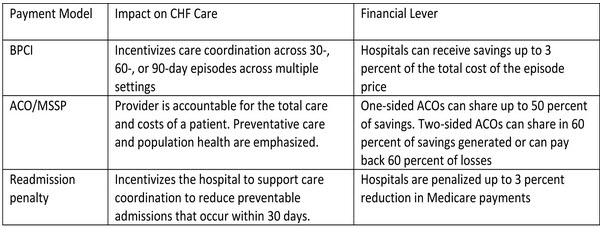

In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) administers the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program, which levies penalties on hospitals with higher-than-expected rates of 30-day readmissions after a heart attack, heart failure, or pneumonia discharge. The figure below compares the BPCI, ACO/MSSP, and readmissions penalties and their possible impacts on CHF care.

Figure 1: Financial Impacts and Payment Models in the Context of CHF Care

The Real World: How Did Two Large Academic Medical Centers Respond To These Incentives?

We profiled the choices made at Colorado and Duke to help provide practical solutions and guidance for clinicians interested in implementing chronic disease care redesign, and to highlight their alignment of clinical innovations and alternative payment models.

CHF presents specific challenges in choosing an alternative payment model. Some of these include:

- Complexity and variability of CHF. BPCI episodes typically fall into one of two categories: medical or surgical. Surgical episodes, such as a knee replacement, can be easier to predict and have less variability regarding the care needed. Medical episodes, particularly chronic, complex conditions like CHF, have a much greater range in care needed — both inpatient and outpatient — which influences a system’s ability to predict costs.

- Financial risk. Providers may be concerned that bundles would underpay for higher-acuity CHF patients. Also, cardiac care is generally lucrative for providers, and efforts to improve quality leading to less fee-for-service utilization may result in lower revenues (so called “demand destruction”).

- Unknown costs. A large portion of CHF costs and care take place in outpatient settings — such as primary care offices, rehabilitation centers, community health centers, and skilled nursing facilities– in which hospital systems may not be able to exercise control.

Choosing Bundled Payments: University of Colorado Hospital

Colorado, which admits roughly 200 patients with CHF each year, focused on using technology as part of their care redesign strategy. They implemented real-time identification of high-risk CHF patients using electronic health records and best practice advisories to trigger standardized order and discharge sets. Clinicians used data to benchmark against national standards and used dashboards to track utilization and quality measures. In addition, they created a “heart failure university” to educate patients to reduce readmissions, ensured follow-up calls within 2 days of hospital discharge, and focused primarily on CHF patients admitted to the hospital.

Colorado selected a 30-day bundle for CHF under Model 4 of the BPCI that went into effect on January 1, 2014, and they expect to enroll 100 patients this year. Under this model, the hospital will receive a prospective, lump sum payment from Medicare and then distribute that payment among all of the providers involved in the episode of care — and if costs exceed the budget, Colorado will absorb the extra costs. They chose not to engage in a riskier 60- or 90-day bundle, since they felt the rehabilitation centers (that is, post-acute care) were not under their control. The major drivers of this decision were:

.

- A single, highly selected bundle minimized risk and allowed a “dip-a-toe-in-the-water” learning opportunity. Leaders felt Model 4 provided a lower risk because it allows hospitals to bundle acute-care services while they ready themselves for taking risk for post-acute care services and hospital readmissions. The total financial risk was estimated to be only $30,000-$40,000 per year, which will be incurred as Colorado prepares for more risk by implementing innovations in electronic medical records, alerts and standardized order sets, and other changes.

- Focus on a highly specified problem. Though long-term care and prevention were important, Colorado leaders wanted to focus specifically on direct innovations in a specific area under direct control — the inpatient setting.

- Strong support from a convening organization. Colorado also relied on the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the facilitator convener contracted by CMMI, to help with complex data analysis and modeling for their BPCI pilot, which was critical logistical support.

Choosing Accountable Care: Duke University Health System

Concerned that the BPCI was not a scalable program, and instead interested in broader population health, Duke pursued the ACO/MSSP model. To address the spectrum of care, the major care innovations at Duke were the initiation of the Same Day Access Heart Failure Clinic to provide acute care outside of the hospital and the Heart@Home program that sought to improve outpatient care. Using a nurse practitioner-driven model, patients access a provider right away instead of showing up at the emergency department. After a patient visit, the clinic conducts a follow-up call or appointment within three days to ensure stability, reconcile medications, and address any patient questions.

Duke enrolled in a community-based, physician-led ACO/MSSP called Duke Connected Care. The following factors influenced Duke’s decision to pass on the CHF BPCI pilot:

- Interest in gaining experience managing post-acute care, a major source of costs variation.The ACO/MSSP model creates strong incentives to minimize costs outside typical 30-90 day bundles. Duke felt this would strongly incentivize long-term structural changes in their care.

- Baseline lower costs of CHF care. Because Duke’s existing CHF costs were low, they felt the margin collected from a short term bundle would be small and not generate substantial savings.

- Broad strategic focus on population-based health. The ACO/MSSP model incentivizes providers to take a more global look at the care provided to the whole patient, and the institution’s vision was to focus strongly on enhanced primary care. Duke’s leadership believed this was a better step towards reform than more incremental changes achieved through the BPCI.

Policy Recommendations and Lesson Learned

Both Colorado and Duke are engaged in a process of care delivery reform, though they chose different alternative payment models to support their delivery innovations. In this manner, both centers took steps towards creating a culture of continuous improvement, which may drive further key innovations. In addition, each center was strongly motivated by the presence of clinical and administrative champions. However, in reviewing the Duke and Colorado experiences, future recommendations also emerged:

Directly reward or penalize clinicians for quality-related outcomes. The payment interventions thus far have not yet demonstrated major impact on meaningful outcomes, such as survival, comprehensive costs of care, readmission, or other quality of life measures. For such small changes to lead to larger ones, clinicians must be rewarded or penalized with clearer connections to clinical outcomes under their control — which would require the creation of numerous financial “microenvironments” through a large organization, with well-designed supportive electronic medical records.

Encourage better coordination and best-practice sharing between various institutions. Though clinical leaders and hospitals pursued innovations in care, hospitals appeared to work in isolation, without clear standardization or sharing of best practices.

Improve long-term incentives for clinical leaders. Though expert clinical leaders spent a great deal of time and effort on redesigning care, those responsible for their institutional promotion (in academic centers) view production of research, grants, and publications as much more important than clinical redesign. As a result, over time, such innovators may “burn out” and not feel their important work is recognized.

Rethink existing Value-Based Purchasing and Pay-for-Performance programs. The ACA established Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program. This has been seen as a separate burden, rather than part of an integrated plan, which dilutes clinician energy. Thus, a consolidation of the VBP program at some point into the BPCI or Shared Savings models would be beneficial.

Establish long-term funding for convening organizations. Though convening organization like AAMC played an important role in seeding CMMI pilot programs, there are no long-term, continuing sources of funding for this crucial role.

Commentary

Op-edPayment and Delivery Reform Case Study: Congestive Heart Failure

April 15, 2014