The annual panic affecting the nation’s physicians is in full swing. “Medicare docs face 24% pay cut… again,” reported CNN Money this month. But after almost a decade of kicking the can down the road, Congress is closer than ever to solving one of Medicare’s most vexing problems. Recently, 3 congressional committees with jurisdiction over Medicare physician payment made progress towards replacing the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR), a mechanism intended to help control Medicare spending. On July 31, 2013, the House Energy and Commerce Committee unanimously reported favorably on HR 2810, a measure to repeal the SGR, and on October 30, 2013, the Senate Finance and House Ways and Means committees released a joint proposal also to repeal the SGR formula and replace it with payment reform. Impressively, there appears to be bipartisan agreement to link SGR repeal with a strategy to move away from traditional fee-for-service payments to physicians.

This recent congressional activity may be the best opportunity to fix the SGR permanently, and the physician community can and should take a leadership role, especially because any SGR fix would demand strong clinician innovation to identify payment and delivery reforms.

In this post, we describe the origins of the SGR and reasons for renewed optimism for a permanent fix.

What Is the SGR?

At its inception in the 1960s, Medicare Part B simply paid what physicians charged, in a practice called the customary, prevailing, and reasonable (CPR) system, which quickly resulted in unbridled spending. Later attempts to curb spending failed, including linking price increases to medical inflation in the 1970s and creating the relative value unit (RVU) system to standardize payments in 1989.

Enter the SGR, when Congress passed the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. It seemed like a good idea at the time. Here’s how it works: physician services, like reading x-rays, performing office visits, or doing operations, earn a predetermined number of RVUs based on the time, energy, and effort of the physician. Medicare multiplies the RVUs by a conversion factor to get a price in dollars and pays the physician. This system considers only the cost side and ignores the quality side of the value equation, paying the same for good and bad outcomes.

The key is that the SGR limits spending on Medicare Part B by setting a spending target, which is linked to the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). Actual spending on physician services (the total number of RVUs times the conversion factor) is then compared with this global target. To control future spending, Medicare adjusts the conversion factor up or down for the next year so all physicians take a proportional increase or reduction to their fees.

Between 1998 and 2001, strong economic growth led to high targets—and higher conversion factors. Physicians made out well. But when the economy stalled in 2002, expenditures exceeded the target, and physician fees across the board were cut 4.8%. When additional SGR-mandated cuts were set for 2003, Congress worried more cuts would drive physicians out of Medicare and postponed them. This was the first of many “patches.”

This has happened year after year. That is, the money for each short-term fix was borrowed from future physician payment and not recorded as an ongoing federal expenditure. By repeatedly overriding cuts over a decade, Congress compounded the gap between actual Medicare spending and where the SGR formula says it should be—to the cumulative total of hundreds of billions of dollars by early 2012.

To address the gap, the SGR mandates a huge 24.4% cut in the conversion factor in January. This is unrealistic, would disrupt care for Medicare beneficiaries, and is causing major anxiety among physicians. But past efforts to repeal the SGR for good, either as part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act or as separate legislation, have failed because repeal would count as a big deficit increase.

Why the SGR Failed

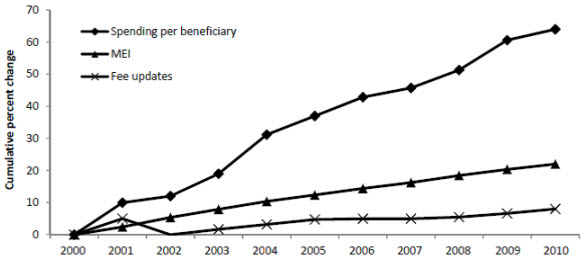

Prices of Medicare services have never explained cost growth, as the lower line in the graph shows; physicians’ fees almost flatlined after 2000, not even keeping up with inflation (shown by the middle line). Spending per patient, shown by the top line, skyrocketed. The explanation is clear: Medicare costs are driven by physicians simply doing more and more. Medicare growth is all about volume. Yet the SGR addresses only price, which perversely makes incentives to expand volume, which triggers additional SGR-mandated cuts, which pressures physicians to further expand volume.

Data from Medicare Payment Advisory Committee, 2011. (MEI, or Medicare Economic Index, is a measure of inflation.)

The SGR also fails to create any incentives to practice efficiently. Suppose a physician is more judicious about her services. She gets paid less that year, is treated no differently than others, and faces later fee cuts. She gets hit twice.

Last year, economists showed that California, Tennessee, and Massachusetts physicians kept Medicare growth below targets from 2003 to 2009, while Florida, New York, and Texas physicians exceeded targets by almost 50% to 80%. In other words, doctors in certain areas performed many more services per patient, without measurable improvements in quality. Even within states with low overall physician spending growth, the Institute of Medicine showed big variation. The same was true in subspecialties. Psychiatrists, general surgeons, and anesthesiologists more than kept their costs under SGR targets, while cardiologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists far outstripped them. Despite this variation, all physicians get cut the same by the SGR formula.

Embedded in the Balanced Budget Act, therefore, was a perverse set of incentives leading to higher Medicare costs. There was no reward for collaboration, no incentive to use resources better, and no incentive to provide better care.

An Opportunity

Last year, due to unexpectedly lower increases in Medicare growth, the Congressional Budget Office reduced the expected cost of a permanent SGR repeal to $140 billion over 10 years—a discount of more than $100 billion compared with prior estimates. It’s likely that this amount might be recouped from the other parts of Medicare, such as postacute care, hospital charges, and prescription drug costs. The continuing focus on an alternative to “sequestration” to address federal budget deficits may also create a legislative opportunity to address this issue as part of a larger fiscal package.

Although finding the precise ways to pay for the fix is not clear, there are potential areas of bipartisan agreement. For example, work from MedPAC, our center at the Brookings Institution, and others has identified areas of potential savings to offset a permanent SGR repeal. In principle, the Obama Administration proposed potential Medicare savings to offset the cost of the SGR repeal, as have congressional Republicans.

Finally, there also appears to be growing recognition on the part of the physician community of the need to reconsider the role of traditional fee for service and the increasing importance of value-based purchasing and alternative payment models. This recognition is important, because physician leadership will be critical to moving the bipartisan SGR reform proposals forward.

Commentary

Op-edIs the Time Right for a Permanent Fix to Medicare’s Formula for Physician Payment?

November 18, 2013