This week more than 600 delegates, including over 50 government ministers, donor agencies, civil society and the private sector are descending on Brussels to cast their vote of support for the Global Partnership for Education (GPE). The GPE is requesting $3.5 billion to replenish its fund for the 2015-2018 period, and gather pledges from developing countries to increase their own education spending. In preparation for this meeting we decided this would be a good time to reflect on GPE’s journey in recent years; on progress made and remaining weaknesses, and what to look for in this week’s proceedings.

The Global Partnership for Education was established in 2002 as the Education for All Fast Track Initiative (FTI), and is the only dedicated multilateral partnership focused on education. Its mission is to “galvanize and coordinate a global effort to deliver good quality education to all girls and boys, prioritizing the poorest and most vulnerable.” It is designed to strengthen national education plans, improve aid effectiveness, coordinate donor support and galvanize financing for education. It does this through a partnership of developing country governments, donor agencies, civil society organizations and private organizations—aiming to make the whole add up to more than the sum of its parts. The High-Level Panel on the post-2015 Development Agenda identified sector specific multi-stakeholder partnerships like GPE as essential to the achievement of any new post-2015 development agenda, as they can bring about much needed change in mindsets about pressing global issues.

So How is GPE Faring?

Four years ago, an extensive evaluation of the GPE (the midterm review of the then-FTI), exposed many crippling problems and concluded that it was a weak partnership, with weak accountability, and did not deliver on its goals. It found that FTI was overly focused on the “finance gap” model, and ignored gaps in capacity, data collection and monitoring and evaluation.

Today, the Global Partnership looks very different from the FTI of four years ago. We reflect on progress against five major goals the organization has set out for itself over the last four years, including reform goals formulated in the midterm evaluation and goals set out one year ago in Brussels by the new CEO. We conclude that progress has been made in a number of areas and that the pace of change has been accelerating more recently. It has taken steps to mobilize more resources, better balance need and performance in country allocations, develop a deeper partnership, monitor results and improve program delivery on the ground.

In many ways the organization, despite its existence for over a decade, has recently been in “start-up” mode. Over the past three years GPE has developed a new governance structure, new board members, new strategy, new policies on fragile states and data, added a number of new developing country partners, a new results-based financing model, and a new secretariat staffing structure and team, to name a few. As with any start-up, there are a number of areas where the organization is still struggling and needs to mature. As the recent conflict in Syria illuminated, the organization has had an identity crisis related to its role in humanitarian contexts, and particularly where pockets of major education needs reside in middle-income rather than low-income countries. Other examples include its struggle to address donor withdrawal from the education sector (such as the Netherlands).

Ultimately, the major question still to be answered is whether GPE can marshal truly significant resources and political support, like its multilateral health counterparts do, to help educate those children and youth who need it most. Next week’s replenishment event will be an important moment in GPE’s development, and it remains to be seen if the international community will double down and invest significantly in GPE. In our view, this is what is needed to ensure that recent progress is built upon for future and greater impact.

What has been the progress?

To get a sense of progress made, we review five areas identified in the midterm review, assess progress made, and highlight outstanding challenges and issues to look out for at next week’s replenishment and beyond

- Mobilizing financial resources. The ability of the partnership to build a fund of significant amount to help countries in need as well as encourage higher education financing domestically is at the core of its function.

Problems: The evaluation highlighted shortcomings in FTI’s efforts to mobilize financing for education both domestically and internationally. It found that the financing gap model was ineffective as an aid mobilization tool, and that the endorsement of sector plans did not have the catalytic effect on support for reform efforts as originally intended. Not much improvement is yet evident. Recently, overall education aid allocation has fallen by nearly 10 percent, and education aid to countries in sub-Saharan Africa has fallen by a shocking 21 percent. Further, GPE has had little teeth when it comes to resisting reduced donor support for education, and managing gaps created by those who have left the sector, like the Netherlands. Additionally, GPE’s own fund is still small. Its first replenishment in 2011 included pledges from 60 organizations and a total of only $1.5 billion to the GPE fund over the 2011-2014 period—an amount that is a far cry from addressing the global financing gap that UNESCO estimates exists of $26 billion annually.

Progress: GPE has taken a number of steps that may help bring in more resources. It introduced a replenishment conference in 2011 to draw more resources into its own fund. Next week will be the second conference. The target for next week’s replenishment is $3.5 billion over three years, definitely up from its target in the first replenishment but under the $4 billion target that the Global Campaign for Education and other civil society groups were recommending. Linked to this replenishment, the GPE has also introduced a new funding model for how it allocates its funds to partner countries. The model promotes a results-based approach at the sector level. It has requirements on external and domestic financing, data and quality education sector plans, but also incentivizes countries to deliver results in results in learning, equity and efficiency areas. This combination of funding for needs and towards incentivizing results is likely to attract new donors to the partnership. The new approach builds on progress seen within developing country budgets. GPE’s Results for Learning Report 2013 showed that domestic spending on education, as a share of GDP, in partner countries increased on average by 10 percent after joining the partnership. However, as the report recognizes, the data is not sufficient to establish attribution to the GPE or tell us why country’s increased their budgets.

Where to go from here? Funding remains a critically challenging area for GPE and the education sector writ large. The problem is not that there are no funds in donor or government coffers but that the education sector has struggled to substantially attract them. This year alone, other multilateral mechanisms in health attracted, for equally important and deserving problems, many times the amount GPE is targeting. For example, in December last year, the Global Fund for AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria raised $12 billion from 25 countries, the European Commission, foundations, corporations and faith-based organizations for the 2014-2016 period, a 30 percent increase over the pledges of $9.2 billion secured for 2011-2013. What the replenishment campaign yields next week will be an important indication of progress on this front. It will also be important to watch if GPE’s new funding model will translate into more diverse funders supporting its work, including the private sector which to date the organization has failed to figure out an effective way to substantially do so.

Balancing need and performance. GPE needs to be able to reach the neediest children while still encouraging performance and maintaining a focus on results.

Problems: The FTI was flawed in terms of its reach, as it struggled to fund the neediest countries due to its focus on rewarding good performers. Most notably, the midterm evaluation highlighted the importance of finding better ways to help children residing in conflict-affected and fragile states.

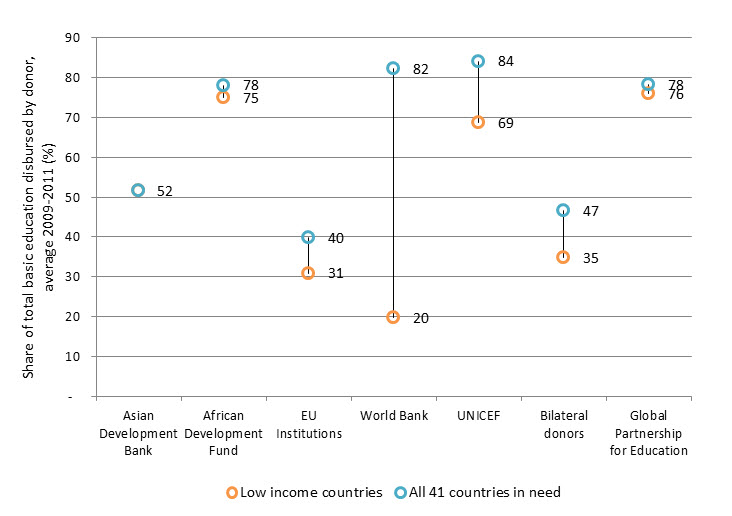

Progress: In 2012, GPE committed to making support for fragile states a strategic priority. Following this decision, a record eight fragile states joined the partnership in 2012 alone. The number of fragile states in the partnership went up from just 1 in 2002 to 17 in 2011 and 28 in 2013, including such countries as Somalia and South Sudan. Today fragile states make up close to half of the total 59 developing country partners in the partnership. Our analysis suggests that among all bilateral and multilateral donors, GPE is currently one of the most successful in reaching countries in need. The figure below illustrates the share of total aid for basic education that is disbursed to 41 countries in need, defined as the 35 low-income countries plus 6 lower middle income countries that have some of the largest out-of-school populations globally. In the case of GPE, 76 percent of total education aid is allocated to low income countries, with a total of 78 percent to the 41 countries in need. In contrast, the respective shares for bilateral donors are 35 percent to low income countries and 47 percent to all 41 countries.

Share of Basic Education Aid to Countries in Need (2009-2011 average)

Where to go from here? While GPE has responded to criticism about insufficient support to fragile states, it is still grappling with the issue of how to address humanitarian crises in non-GPE countries. Because it only funds low-income countries, it has not in any meaningful way helped the thousands of children affected by the Syrian crisis, even though clearly the needs are great. On the other hand, GPE has committed to accelerated funding in Somalia to help advance education services in the humanitarian response. It will be important to watch how the partnership decides to resolve its engagement in humanitarian contexts and perhaps most importantly they will need to lay out a consistent strategy and financing modalities so that other actors will know what they can and cannot expect from GPE.

- Moving towards a true partnership. It is important that GPE acts as a partnership where the interests of developing countries and donors are aligned, as it seeks to further the aid effectiveness agenda laid out in the Paris, Accra and Busan agreements.

Problems: A major problem with GPE was its initial governance structure as a donor organization, lacking input from developing countries. At its inception the partnership included only seven developing countries and only one developing country was a member on the steering committee. The 2010 midterm review blamed this imbalance for the partnership failing to become a true “compact.”

Progress: This concern has been largely addressed with the new constituency-based governance structure that started in 2011. The board is now made up of constituencies of actors (e.g. donors, multilateral institutions, developing countries, civil society, the private sector) with an equal balance of developing country and donor partners. Every developing country partner that joins the partnership is represented on the board through one of the constituencies.

Where to go from here? Today, engagement with developing country partners is no longer the problem but, rather, engagement with donor partners is. The developing country constituencies are regularly represented on the board by ministers of education, but the donor representatives rarely engage their ministers or top officials, nor do the foundations and private sector engage their top staff. Recently, the profile of the organization has been raised with its new board chair, former Prime Minister of Australia Julia Gillard. It will be important to watch how the level of representation and engagement in the GPE board evolves in the future and whether it can play a global leadership role in keeping partners of the partnership to their commitments.

- Monitoring and evaluating results. In order for GPE’s investments to have an impact, its activities and process must be properly monitored and evaluated to assess what works and what doesn’t.

Problem: The midterm review found that FTI could not establish if its inputs, let alone outputs, were being achieved due a lack of monitoring and evaluation during implementation.

Progress: The secretariat has now established a monitoring and evaluation unit, and is working toward an open database for developing country partners on 57 key indicators. Additionally, to enable improved monitoring of its own financing flows, GPE is taking a much needed step by beginning to report to the OECD-DAC next month. GPE affirms its commitment to data and evaluation in their new funding model and with the call for pledges to join the “data revolution” at the replenishment.

Where to go from here? The partnership’s ability to follow through with monitoring and evaluation efforts remains to be seen. This will include providing sufficient support at the country level to improve monitoring systems. A comprehensive evaluation of the GPE is planned for 2016.

- Program Delivery. Further strengthening of the overall capacity of the secretariat and the GPE partners to support the implementation of Education Sector Plans in a timely manner is deeply critical to the success of the partnership in the years ahead. Successful implementation will also depend on the extent to which the partnership has a clear strategic focus and is able to work effectively using its partnership and financing mechanisms.

Problem: The midterm review found that involvement past the endorsement stage was often minimal. GPE’s mission includes providing technical assistance and helping address capacity gaps, but the level of support varied widely. Programs have at times been slow-moving and delays in implementation due to procedures with the supervising or managing agency have averaged 13-14 months. The secretariat lacked capacity, and its focus was on helping countries with grant application preparation, taking two-thirds of its time on this task. Finally, GPE was widely criticized as inefficient due to the hosting agreement within the World Bank.

Progress: To build capacity the secretariat has been growing and adding staff, at the request of the new CEO. Additionally, the secretariat has also spent more time in technical assistance, making 126 country visits in the last two years—mostly assisting countries in developing education sector plans. In 2011 a new GPE fund was also launched, consolidating the previous catalytic and Education Program Development Fund funding structures. The GPE now offers three types of grants. Its central and largest funding mechanism is the Program Implementation Grant focused on program delivery. This year, a new hosting agreement with the World Bank was also reached in which the secretariat will receive more flexibility to respond to the changing operational and financial landscape in education.

Where to go from here? GPE’s new funding formula expands its scope to a larger and more varied number of countries, all of which will need to be managed carefully in order for the partnership to be effective. Further strengthening of the capacity of the secretariat will be needed to manage this extended scope. The partnerships management and financial instruments will also need to evolve and evaluated to ensure they match the GPE’s expanded ambition.

The Bottom Line

Our assessment shows that while imperfections remain and further progress needs to be made in a number of areas, the GPE is now performing much better and can productively absorb an increase in its funding. Funders cannot use the excuse that they have no confidence that their funds will be well-used or well-monitored. The recent declines in donor funding for basic education are denying many poor families the chance to break the intergenerational transmission of poverty through education. These reductions should be immediately reversed. The GPE has an important role in making this happen.

Commentary

Op-edIs the Global Partnership for Education Ready for Takeoff?

June 23, 2014