Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

This article first appeared in The Economic Times. The views are of the author(s).

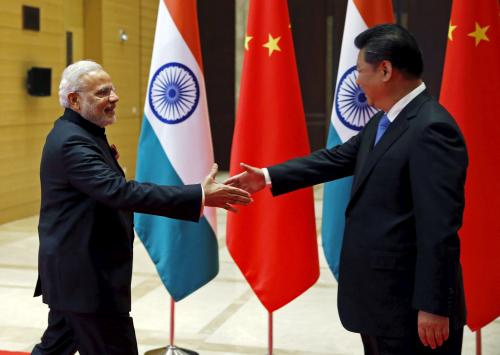

What does India want from the world? It’s quite clear, really: international partnerships to accelerate its domestic development, a stable and conducive periphery, a multi-polar Asia, an end to cross-border terrorism and a sufficient role in global governance to enable it to meet these goals. Today, each of these objectives relates in some way to India’s relations with China.

Until recently, India’s aspirations required it to forge a complex and somewhat contradictory relationship with Beijing. From the early 2000s, India deepened trade and economic relations with its northern neighbour and collaborated with China in creating space for rising powers on global governance – including through the BRICS, the BASIC coalition on climate change and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

At the same time, India took measures to address the military imbalance along its disputed border with China, and kept a wary eye on Beijing’s political and military relations in its neighbourhood, especially its support for Pakistan (which extended to the transfer of nuclear and missile technology).

But things have now changed, and faster than many believed possible. The 2008 financial crisis, the half-heartedness of former US president Barack Obama’s “pivot to Asia” and now Donald Trump’s “America First” policy have accelerated China’s relative rise in the international system. And that rise has been accompanied in China by stronger centralised governance, enduring mercantilism, more assertive territorial revisionism with neighbours and a continued disregard for certain international norms, including on cyber security and freedom of navigation.

For India, China now factors everywhere. A balanced and sustainable economic partnership is still necessary for India’s development. At the same time, China plays a more active economic, political and military role in India’s near abroad and Beijing provides cover for Pakistan’s continued support for cross-border terrorism. Under President Xi Jinping, China projects itself as ascendant, leaving little space either in Asia or on the world stage for a rising India, whose transition into a middle-income country will take place over the next two decades.

China’s ascendance is most evidently on display in its plans for One Belt, One Road (OBOR) or the Belt & Road Initiative, the subject of a major summit in Beijing this month. While many of its neighbours sent heads of state or government, or ministerial delegations, India was notably absent. India’s public rationale for its opposition to OBOR has long been that the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) ran through Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (PoK), and was thus a violation of Indian sovereignty. But New Delhi’s concerns have long run deeper, and extended both to CPEC and to the Maritime Silk Route.

Who Will Benefit?

India’s response to OBOR, by necessity, rests on a set of assessments. Is OBOR a commercial project, with viable financing intended to benefit both China and host countries? The evidence for this is weak. Sri Lanka is but the starkest example. Chinese support to its former leader Mahinda Rajapaksa led to the building of white elephant infrastructure projects (including what has been described as “the most underused international airport on the planet”) , massive national debt and the translation of that debt into political influence – which in turn had security implications. The gradual development of Chinese military or “dual use” facilities in Djibouti and Gwadar, and the creeping militarisation of the South China Sea, offer clear indications of long-term Chinese intentions in the Indian Ocean region.

While India’s reservations about OBOR have been hinted at for years, including by the prime minister, China’s public exhortations for Indian participation at the May summit required a clearer articulation of Indian concerns. This came in the form of a statement last week that stressed India’s desire for greater regional connectivity, but laid out specific criteria. Connectivity projects must be financially responsible and not create an “unsustainable debt burden”. Additionally, they must reflect environmental considerations, be based upon a “transparent assessment” of costs, and involve the transfer of skills and technology to ensure their long-term maintenance by local communities. And, of course, they must respect countries’ sovereignty and territorial integrity. This is a clear set of normative standards, one that China, recipients of OBOR-linked largesse and other actors — including in Europe, Japan, and the United States — would do well to heed. In fact, EU participants echoed these sentiments by blocking a statement at the Belt and Road Summit on trade, on the grounds that it was not based on “transparency and co-ownership”.

Does India have a lot to lose from boycotting OBOR? Not necessarily. China’s investment into India has risen considerably since 2014. According to Indian government figures, $800 million in Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) came into India in just 17 months between April 2014 and September 2015, more than double all previous Chinese FDI to India. This is on a similar scale to estimates of Chinese FDI into Pakistan under CPEC, and is simply indicative of the immense push factor of excess Chinese capital. If it can be invested in India in a manner that meets New Delhi’s stated criteria, it would naturally be mutually beneficial. However, drawing lines upon a map in a unilateral fashion, not just in India, but across Asia and the Indian Ocean region, is a far more sinister matter.

One Belt, One Road will only be a success if it is pursued in a more transparent, status quo-oriented, market-driven and responsible manner. That would be welcome. India has staked out a clear position. Others may arrive at the same conclusions the hard way.

Commentary

Op-edIndia doesn’t have a lot to lose by boycotting OBOR. Read why

May 22, 2017