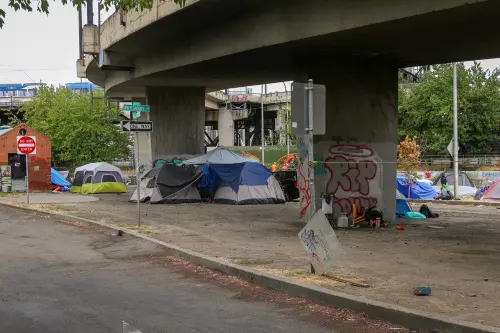

For several years grassroots activists have argued that “environmental racism” too often characterizes the way society allocates pollution and hazardous chemical exposures. In the years since Love Canal a multi-ethnic (black, Latino, Native American, and Asian American) movement for “environmental justice” has coalesced around the belief that low income and minority communities have too often either been turned into dumping grounds—targets for toxic landfills, incinerators, and various dirty industries—or been quietly victimized by lax environmental enforcement.

The environmental justice movement has won significant local and national victories, blocking outright or negotiating changes in, numerous planned facilities. In a major 1994 political breakthrough for the movement, President Clinton signed an executive order instructing the federal government, not just the Environmental Protection Agency, to start “identifying and addressing, as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects” among low income and minority populations.

Taking the executive order to heart, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Atomic Safety and Licensing Board last May rebuffed an application to build a uranium enrichment plant between two African American neighborhoods in Louisiana. The board relied heavily on scholar-activist Robert Bullard’s testimony that the site selection process did not adequately assess relevant environmental, social and economic impacts. In September EPA held up the permit for a vinyl chloride plant in Convent, Louisiana on similar grounds. EPA is now casting about for ways to show commitment to environmental justice, especially by bringing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act (which bars discrimination by recipients of federal funds) more forcefully into play.

On the judicial front, the black residents of the Kennedy Heights neighborhood in Houston are in federal court seeking as much as $500 million in damages, alleging that cancer, lupus, and other adverse effects can be traced to crude oil residues that contaminated first the soil on which their homes were built and thereafter their drinking water. The defendant, the Chevron Corporation, denies any unusual pattern of illness in Kennedy Heights, and claims that the company has done nothing injurious. A victory by the residents would mark the first favorable court ruling on a claim of environmental racism. “Race has been injected into this case as a litigation strategy,” asserts Chevron’s lawyer Robert E. Meadows. “I think it’s wrong.”

This playing of the environmental race card is, to say the least, a major public health distraction for minorities. And we will surely see much more of it, especially if the Kennedy Heights residents win their lawsuit.

Epidemiologists and toxicologists have found the concept of a disease “cluster” extremely useful for unraveling infectious diseases (like AIDS), occupational illnesses (like cancer among vinyl chloride workers), and effects linked to isolated products (such as bacteria-tainted hamburger and experimental drugs). But as both the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Public Health Association point out, attempts to link apparent clusters of noninfectious disease to general environmental factors outside workplaces (where exposures can be strikingly high) rarely succeed. In large populations, clusters can appear randomly or because of the way cases are counted. Sometimes the number of verifiable cases of a condition is simply too small to permit confident causal inference.

It seems never to occur to activists that any significant public health price must be paid for cranking up citizen outrage against weakly documented (and possibly ephemeral) hazards. But time and money spent chasing chemical chimeras will be unavailable to expend against well-established causes of preventable and treatable disease.

Many such health conditions disproportionately affect minorities and the poor: AIDS, asthma, obesity (especially among African American women), hypertension, diabetes, and so on. Popular attention to these things, and to a short list of significant environmental hazards faced disproportionately by the black poor (such as residential lead paint), is now threatened by a national environmental justice agenda so utterly shapeless as to embrace almost any environment-related grievance or aspiration espoused by any claimant of color. I’ve attended many meetings devoted to environmental justice, and heard a fair amount about the possible hazards of environmental “endocrine disrupters.” I’ve never heard tobacco mentioned once.

This problem of skewed or missing priorities will only worsen should the residents of Kennedy Heights win their lawsuit. The biggest winner by far would be John O’Quinn, the prosperous Texas attorney who aims to do for Kennedy Heights what he has already done for his clients in silicone breast implant litigation. If he can make Chevron pay, trial lawyers across the country will begin trolling for “poisoned” minority neighborhoods to represent. And communities of color will thus have yet another powerful distraction taking their eyes off the real prize of public health.

Commentary

Op-edDown in the Dumps, On Purpose

November 4, 1997