George Floyd’s death at the hands of police in May 2020 and frequent events like it across America have added new urgency and momentum to the drive to reform our criminal justice system. Unfortunately, the debate has too often collapsed into an unhelpful binary: “support the blue” or “abolish the police.” Either of these poles would tend to have a negative impact on the very communities that have suffered disproportionately under our current criminal justice and law enforcement policies. Excessive policing and use of force, on one hand, and less public safety and social service resources on the other, can both be detrimental to communities that are exposed to high levels of criminal activity and violence. We must find a path of genuine reform, even transformation, that fosters safer, more peaceful, and more resilient communities.

In this volume, available to be downloaded as a full PDF here or to be read online as individual chapters below, experts from a broad spectrum of domains and policy perspectives offer policymakers with research-grounded analysis and recommendations to support sustained, bi-partisan reforms to move the criminal justice system toward a more humane and effective footing.

Police reform

Authors: Rashawn Ray, Clark Neily

The deaths of unarmed Black Americans, including George Floyd, Elijah McClain, Breonna Taylor, and many others, at the hands of police are leading to calls for sweeping police reform. In Chapter 1, our experts lay out a series of sensible police reform ideas shared across the political spectrum, including reforming qualified immunity, addressing officer wellness, and changing the culture of “us versus them” policing.

Downloads:

Reimagining pretrial and sentencing

Authors: Pamela K. Lattimore, Cassia Spohn, Matthew DeMichele

America’s incarceration rate is the highest in the world, a condition rooted in policies and practices that result in jail for millions of individuals charged with but not convicted of a crime and lengthy jail or prison sentences for those who are convicted. In Chapter 2, our experts argue that there is an urgent need for a pretrial justice and sentencing strategy that will reduce crime and victimization, ameliorate unwarranted racial and income disparities, and reclaim human capital lost to incarceration.

Downloads:

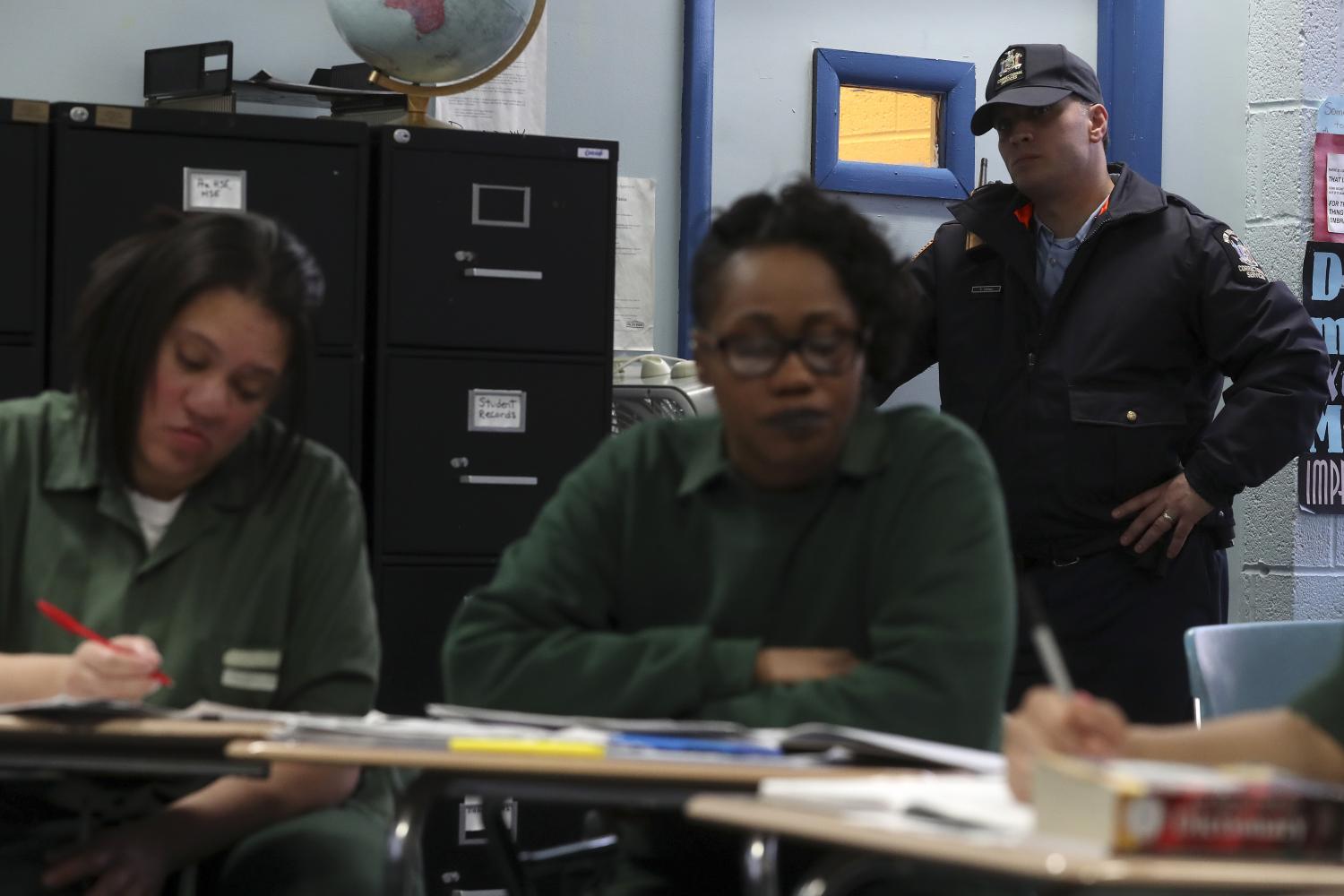

Changing prisons to help people change

Authors: Christy Visher, John Eason

Most imprisoned people will be released into society, but are they prepared to rejoin their communities and avoid a return to prison? In Chapter 3, our experts note that the lack of vocational training, education, and reentry programs makes reintegration difficult for the formerly imprisoned. They propose programming such as cognitive behavioral therapy, education, and personal development to help ease this transition.

Downloads:

Reconsidering police in schools

Authors: Ryan King, Marc Schindler

Although rates of juvenile crime and arrests have declined in recent decades, the rash of school shootings since Columbine in 1999 has catalyzed federal funding for more police in schools. But these school police officers have been linked with increased arrests for non-criminal, youthful behavior. In Chapter 4, our experts offer ways to reimagine public safety in schools and change the dominant but increasingly unpopular law enforcement paradigm.

Downloads:

Fostering desistance

Authors: Shawn D. Bushway, Christopher Uggen

What makes people returning to civilian life from incarceration desist from committing crime? In Chapter 5, our experts review the literature on “desistance,” the study of why and how people stop committing crimes. They note that many people who become involved in the criminal justice system had never fully entered a pro-social adult life to begin with, and so programs designed to foster their “re-entry” into society should focus on fostering adult development.

Downloads:

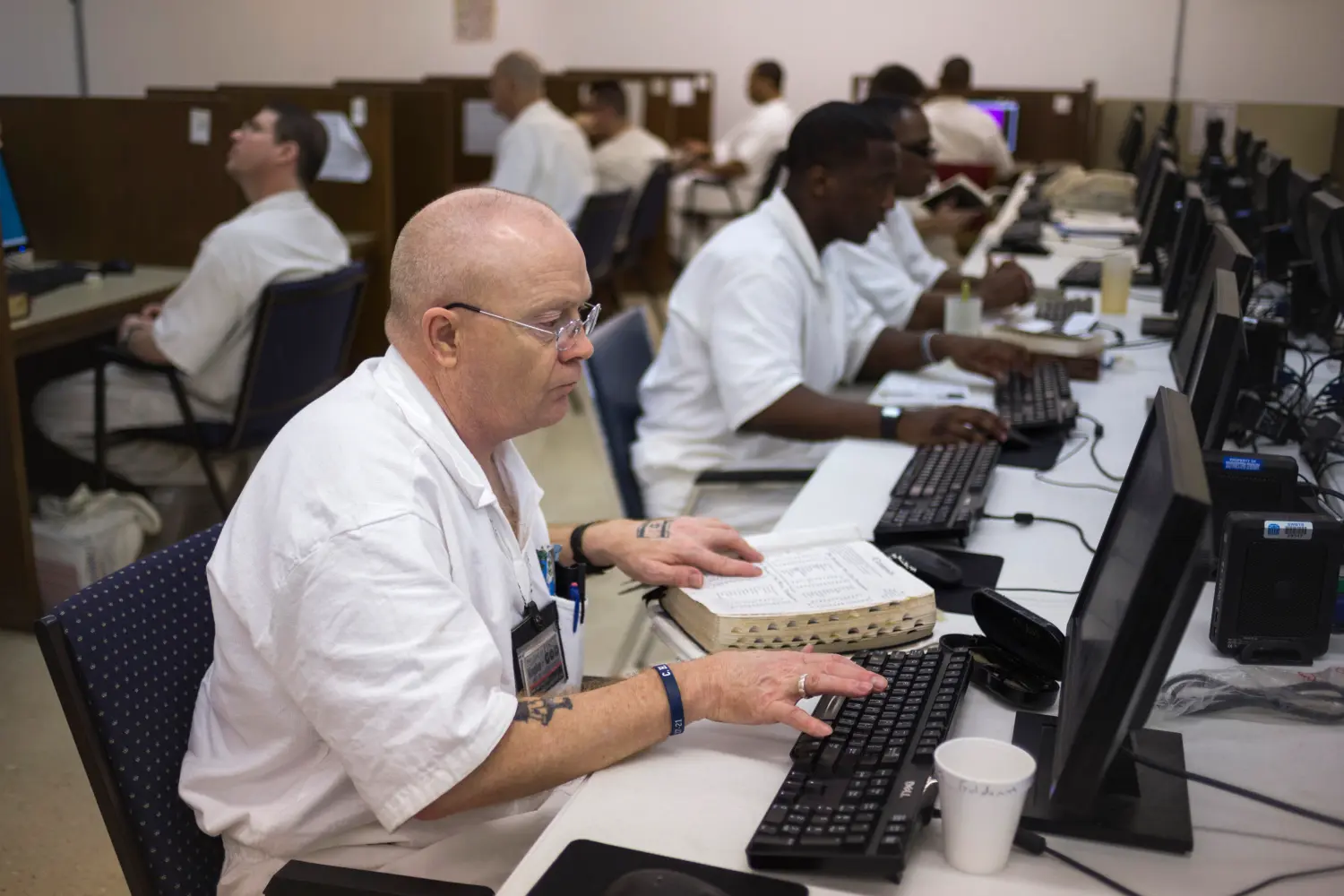

Training and employment for correctional populations

Authors: Grant Duwe, Makada Henry-Nickie

People involved in the criminal justice system tend to be undereducated and underemployed compared to the general population, and post-release employment rates eventually return to pre-prison levels. In Chapter 6, our experts call the employability of returning citizens a “moral imperative,” and so recommend policies designed to increase educational attainment and employment training for incarcerated individuals.

Downloads:

Prisoner reentry

Authors: Annelies Goger, David J. Harding, Howard Henderson

Over 640,000 people return to their communities from prison each year, but more than half of the formerly incarcerated do not find stable employment in their first year of return, and three-quarters are rearrested within three years. In Chapter 7, our experts offer a range of policies to improve reentry outcomes and increase racial equity in the criminal justice system.

Downloads:

Authors: Rashawn Ray, Brent Orrell

As we prepare to exit pandemic conditions, it is a crucial time to address criminal justice reform in America. In the Conclusion to “A better path forward for criminal justice,” our experts recommend a strategic pause to gather data that will help us understand why criminal activity has gone up in recent months and inform both immediate responses as well as longer-term initiatives.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The editors would like to thank Samantha Elizondo for her work on the project, particularly with chapter summaries and editing of the report.

Support for this publication was generously provided by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of its authors and do not represent the views of the Foundation, their officers, or employees.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusion and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its authors, and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research is a nonpartisan, nonprofit 501(c)(3) educational organization. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. AEI does not take institutional positions on any issues.