Why state and local relationships matter to national prosperity:

In February 2021, over 40,000 residents of the city of Jackson, Miss. lost access to clean running water for at least a month, following a historic winter storm that damaged an out-of-date and under-resourced infrastructure system. The mayor, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, said the city would need $2 billion to repair and upgrade the water-sewer system—an amount impossible to afford alone for a city with a $300 million annual budget and a high share of low-income residents.

The next month, backed by the city council, Mayor Lumumba requested $47 million in state and federal funding from Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves to fix the city’s water treatment facilities. But Jackson received just $4.6 million out of the $356 million being doled out during that round of statewide capital projects—a mere 1.3% for a capital city comprising 5.2% of the state’s population and anchoring a metro area that contributes 24% of the state’s economic output.

Even as the state’s business community attempted to facilitate support for solutions, by the end of 2022, poor and unsafe water service was still the norm in Jackson. Relations between the state and city stalled, and the federal government intervened with a series of actions, including approving $600 million to directly address the water crisis.

The breakdown between Jackson and the state of Mississippi reveals a broader trend: a coarsening of state and local relationships that could threaten the transformative use of billions in federal infrastructure funds and other investments flowing to states and local communities.

For many local and regional leaders, these investments could not come at a better time. With boosts in innovation, workforce development, housing, and other place-based assets, the investments are poised to supercharge leaders’ efforts to modernize regional industry clusters and build more dynamic, equitable, and resilient economies. And these federal investments could accelerate state ambitions too. States are eager to advance innovation, support high-quality job creation, pursue clean energy solutions, and embrace nontraditional career pathways in regions that are home to the industries, community colleges, and natural assets critical to state economic success. In short, the nation needs strong local and regional visions as well as intergovernmental cooperation if these once-in-a-generation investments are to effectively elevate American competitiveness and inclusive prosperity.

Instead, state and local tensions are hardening. Over the past decade, states are preempting local decisionmaking more frequently and more harshly. Partisan culture wars are dominating state legislative sessions and prompting states to exert control over multiple policies that were once determined locally. Meanwhile, local employers and regional business groups are caught in the crosshairs, with some business leaders under assault for their efforts to advance economic inclusion and a tolerant workplace.

There is a need for a constructive state and local relationship in every state. However, the combination of harsh preemption and political polarization is most acute in the Midwest and South, where the majority of the nation’s African American and Latino or Hispanic population live, and where solutions to economic transitions and paths to upward mobility are most needed.

When states strip power from localities, they can hurt community problem-solving and state-local coordination around matters of revitalization and opportunity. It can lead to a chilling effect on creative local initiatives in both big cities and small towns, just as they are trying to attract and retain all kinds of workers in the post-pandemic remote and hybrid work environment. It can erode trust and complicate the intergovernmental delivery of key economic development, workforce training, or infrastructure modernization programs that help urban and rural regions prosper.

The purpose of this report is to remind state and local leaders why their collaboration matters. While there are genuine policy differences on issues of race, gender, and crime reduction to work through, the resulting state hostility toward cities can negatively impact joint approaches to economic prosperity and place-based opportunity—goals which states, local leaders, and multisector groups often share.

The report starts with an overview of the economic investment window just as state and local dynamics are deteriorating. Because states are in the drivers’ seat, the report then argues that cities and regions are important to states and statewide prosperity, with new data analysis on metro areas’ economic contribution to their state economies. The report closes with ideas for how state and local leaders can reforge a constructive partnership around the economy, infrastructure, and shared prosperity. With the U.S. eager to expand its innovation and talent capacity and voters tired of the nation’s deep divisions, state and local leaders have a critical window to address both. Together, they can proactively advance an inclusive economy and strengthen public trust in governing, which is core to a strong democracy.

State and local coordination on the economy matters. State and local agencies as well as regional and civic institutions have long worked together around economic development, education, workforce training, infrastructure, and community revitalization, thanks to the nature and flow of taxpayer funds in each state around these strategies. More recently, state and local leaders managed a public health crisis and reopened the economy as the global pandemic evolved.

Today, the federal government has stepped up, with real dollars at stake. Together, the American Rescue Plan Act, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, CHIPS and Science Act, and Inflation Reduction Act will make over $1 trillion in strategic place-based investments to extend tech innovation and economic revitalization to more urban and rural regions. The new funding will reward state and local efforts that boldly address the stubborn economic and geographic disparities in today’s digital economy and promote America’s competitiveness. That includes growing high-quality jobs; improving the skills, incomes, and wealth of a diverse array of workers and entrepreneurs; making neighborhoods vibrant and affordable; protecting communities and industries from the ravages of climate change; and strengthening advanced manufacturing, supply chains, and other sector specializations.

While some criticize the federal spending, most state lawmakers and governors have embraced the practical benefits of improved infrastructure and stronger local semiconductor and advanced manufacturing industries. Meanwhile, local and regional interest has been high; more than 500 urban, rural, and tribal communities from all 50 states applied to a $1 billion federal economic revitalization grant program and a $500 million workforce training program in the American Rescue Plan Act. All told, these federal investments will attract and leverage other public, private, and philanthropic resources to ensure transformative initiatives are effectively implemented and enduring.[i]

Functioning state and local partnerships are critical to ensure smart, coordinated planning and implementation of these investments. For instance, federal infrastructure funds for roads, water, and broadband primarily flow to states before they are allocated to communities—requiring states to be aware of and responsive to local conditions and priorities. Competitive grant opportunities in the new federal legislation may encourage local and regional applicants to seek state matches or partnerships, or at least trigger coordination so that state and local entities are not directly competing for the same grants.

Yet this unprecedented investment agenda comes just as some states are proactively undermining cities and local entities through preemption and other top-down controls.

What happened? First, it’s important to emphasize that states govern cities. States formally set the governing and taxing authorities of local governments. State preemption of local authorities takes a number of forms and is not new nor inherently good or bad. It historically involved legal determinations on whether or not local jurisdictions had the authority to exercise some variations within existing state laws. Further, both Republican and Democratic state leaders have used their powers to preempt local laws. For instance, Democrat-led California recently passed a law to ban single-family-only zoning, effectively preempting local exclusionary zoning practices that have contributed to the state’s affordable housing crisis. In contrast, the former Republican governor of Arizona banned cities from mandating local inclusionary zoning ordinances for fear of over-regulating the real estate sector.

What is new about this dynamic is the stricter and more punitive limits on local authorities, which coincided with a dramatic shift toward one-party rule in state governments. As Table 1 shows, in 2000, the number of state legislatures led by Republicans and Democrats were nearly evenly distributed (18 and 16, respectively), while 15 legislative chambers had “split” party control between their House and Senate. By 2022, however, nearly all state legislatures had flipped to one-party rule. While Democrats added two state chambers and governorships to their column in the 2022 midterm elections, Republicans retain a grip on most state legislatures and have trifecta one-party rule of 22 states, compared to 17 states with unified Democratic control.

As states became more politically “red” over the last two decades, they governed cities and metro areas that became economically more powerful and more racially and ethnically diverse. Since 2000, the 100 largest metro areas increased their share of the nation’s economic output (Table 2), and the residents who live in most of those metro areas are no longer majority-white (Chart 1). The 50 largest cities—mostly led by Democratic mayors—are even more diverse, with people of color making up 64% of the population.

This dynamic has set up a clash between red states and blue cities, in which states are imposing limits, reversals, and punishments of local efforts in greater frequency and intensity. From 2011 to 2019, the quantity and reach of preemption laws expanded dramatically to prevent local adoption of laws and regulations governing job quality, such as the minimum wage and sick day allowances. State leaders have overturned voter-approved local ballot measures, such as a Milwaukee measure to expand paid sick days and Nashville, Tenn.’s passage of local-hire laws. More recently, Florida, Virginia, and Missouri have taken strong actions to ban books, limit the teaching of race and gender in schools, and preempt local efforts to protect and manage the environment.

Studies by Columbia Law School, the National League of Cities, and the Local Solutions Support Center have documented the uniquely punitive nature of recent preemption measures. Arizona’s SB 1487 is a case in point: Passed in 2016, the measure strips power from cities by formally giving the state the authority to withhold critical revenue-sharing funds from local jurisdictions if they violate state laws.

The states with the highest rates of preemption are in the Midwest and South, which are home to most of the nation’s older industrial cities and Black-majority cities. Local and regional leaders in these places have long grappled with sluggish economic transitions, racial segregation and white flight, and disinvestment and poverty. To stem the weakening local fiscal base, leaders try to adopt affirmative visions and strategies, forge strong public-private-university partnerships, and engage their states.

Recent events out of Alabama show how much of a challenge this can be. In 2015, the Birmingham city council approved an ordinance to raise the city’s minimum wage to $10.10 an hour. The goal was to reduce working poverty and improve the economy in one of the very few states that sets no minimum wage and instead follows the federal minimum of $7.25. But the Alabama state legislature blocked Birmingham’s ordinance from going into effect and passed a law prohibiting localities from enacting their own wage laws. A few years later, in 2020, the mayor of Montgomery and its city council approved a new occupational tax to help the fiscally strapped city pay for public safety, schools, and other essential public services. The Alabama state legislature reacted by passing a law preventing cities from imposing new occupational taxes. Both Birmingham and Montgomery are majority-Black cities led by Black mayors. While there may be legitimate policy differences, this power dynamic—in which predominantly rural and exurban state lawmakers limit local problem-solving in large cities—makes its challenging for local leaders and their business allies to create the conditions for inclusive economic growth and revitalization.

As the legal scholar Richard Briffault has noted, what is unique and concerning about this period of governing is the aggressive nature in which states are overriding “widespread state constitutional commitment to home rule” and ignoring the important role of local governance in our federalist democracy. As the nation prepares to make unprecedented investments in economic competitiveness, climate protection, and shared prosperity, the question now becomes whether state and local leaders can engage in a new era of intergovernmental bipartisanship and realize the importance of local governance and metro economies as a source of common ground.

State lawmakers and executives may treat their legislative and culture clashes with cities as separate from their collaborations on infrastructure, workforce, and economic development. But state punitive actions on cities still may affect these economic aims.

That’s because cities are the economic engines for states, the nation, and the globe. Cities anchor metro areas, which are, by definition, labor market and commuting sheds consisting of economically connected counties and core cities that share jobs and workers. Thanks to new technologies and travel options, commuting sheds continue to widen, such that most metro areas include many exurban and rural communities within them. In fact, according to the Census Bureau, 54.4% of rural residents live inside a metro area. As of the 2020 census, there are 384 metro areas in the United States (not including Puerto Rico), which serve as clusters for jobs, industries, and talent in their states and the wider nation.

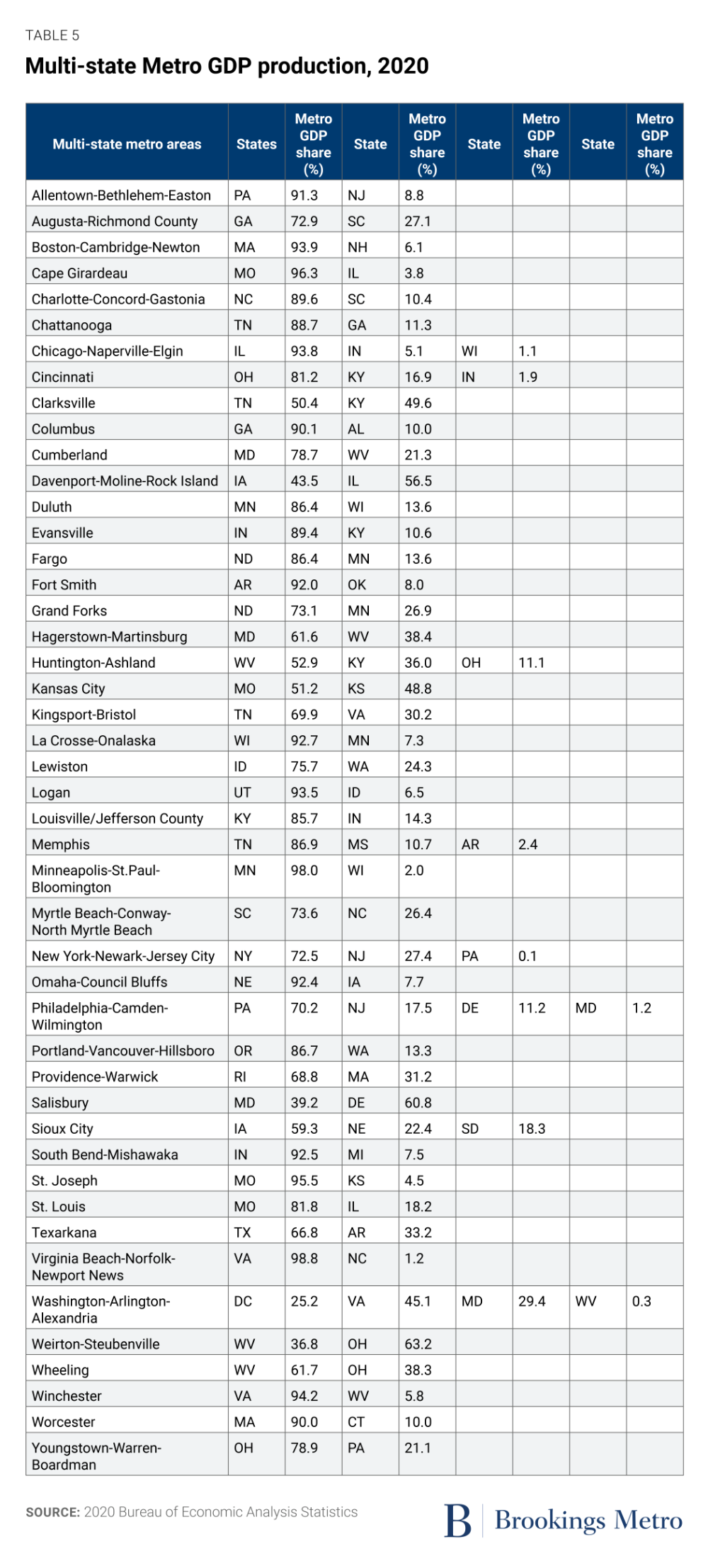

This section examines the economic contribution of all 384 metro areas to their respective states.[ii] To do that, we use 2020 census data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis to calculate the individual and total share of metro area gross domestic production (GDP) in each state and the District of Columbia. GDP is defined as the total market value of goods and services produced in a given geography. Thus, metro-level GDP is an important measure of the total income generated by the private sector firms, universities, and government activity in the metro area. Readers can find data on the size and contribution of metro area GDP to the state economy in this interactive tool.

Here are a few highlights from that data:

Metro areas generate the majority of state economic output in 46 out of 50 states.

In 2020, metropolitan areas were the main economic drivers (meaning they represented more than 50% of state GDP) for all but four states in the nation. So, in red and blue states alike, metro areas are major sources of jobs, revenue, and opportunity.

In 10 states, metro areas produced nearly 95% or more of their state’s economic output, reflecting the highly urbanized nature of those states’ economies. Even traditionally “rural” and natural-resources-dependent states such as Alaska, Iowa, and South Dakota were predominantly powered by their metro areas.

Metro economies play a particularly outsized role in the Northeast and West.

Metro economies in the Northeast and West regions of the U.S. produce 94.7% and 92.9% of those regions’ GDP, respectively. In comparison, metro areas in the Midwest and South generate 82.3% and 87.5% of state GDP on average, respectively.

There are several factors that may explain why. For one, the Northeast and West are home to major tech hubs such as Greater Boston, New York, and San Francisco-San Jose, Calif. These two regions also have large swaths of federally protected lands that serve to concentrate jobs and people in large metro areas. Finally, counties in these regions (New England in particular) are geographically large, so their metro areas incorporate more exurban and rural territory than in many states in the Midwest and South, where counties are smaller.

In 18 states, one large metro area dominates the state’s economy.

In more than one-third of states, a single metro area produces 50% or more of its state’s GDP. These include the Salt Lake City (Utah) and Seattle (Washington) metro areas in the West; Chicago (Illinois) and Minneapolis-Saint Paul (Minnesota) in the Midwest; Boston (Massachusetts) and Portland (Maine) in the Northeast; and Atlanta (Georgia) in the South. Of note is that the New York-Newark-Jersey City metro area generates over 75% of the GDP for both New York and New Jersey.

A number of these outsized metro areas are “superstar” cities that house high-tech assets. Others are also capital regions with public sector jobs that add to their industry mix and economic stability. In nearly all cases, states have tried to better connect these large metro areas to smaller cities and rural towns (such as through supply chains, “farm-to-table” initiatives, and education exchanges) in order to extend economic gains statewide. In general, these metro areas’ outsized presence serves as a global brand for their home states and disproportionately shapes their states’ economic fortunes.

There are 46 metro areas that reach across state lines, bringing shared economic value to 37 states.

Approximately three-quarters of U.S. states share a metro economy with a neighboring state, indicating the importance of cross-border coordination in growing jobs and the economy. Of the 46 multi-state metro areas, 38 span two states; one example is the Chattanooga metro area, which generates economic value for both Tennessee and Georgia. Another six metro areas span three states, such as the Cincinnati metro area, which touches Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana. Finally, two metro areas span four states: Greater Philadelphia and the Washington D.C. metro area.

The existence of so many multi-state metro areas means that state actions to steal jobs from a neighboring state is yet another example of state actions that undermine cities and metro areas. The most egregious illustration was last decade’s “border war” between Kansas and Missouri, in which both states attempted to move jobs and businesses in the Kansas City metro area to their side of the state line, resulting in zero net new jobs for the region—at taxpayers’ expense.

As stated earlier, pre-emption is not new. State and local leaders will naturally disagree on key policy areas or which level of governing is best to address matters closest to local constituents. However, today’s “new pre-emption,” which is more ideological and punitive in nature, can have far-reaching consequences that negatively impact residents and businesses well beyond city limits.

When states undermine metro economies, they undermine rural economies too

When rural-dominated state legislatures overrule decisions in urban areas, they perpetuate a zero-sum dynamic that fails to recognize that rural communities and metro areas are interdependent and share common needs.

Urban and rural prosperity are linked. Cities and metro areas generate statewide revenues that support rural needs and provide small town entrepreneurs with access to customers, financial capital, and other services. In fact, rural areas located near cities fare better than remote rural areas, meaning that a network of small and midsized cities in states can create a win-win approach to broadening opportunity. In return, urban and suburban residents and businesses benefit from the natural resources and assets found in rural communities. Hence, many recent winning regional innovation strategies span urban and rural communities.

Urban and rural communities depend upon place-based strategies to address pockets of advantage and disadvantage. Cities and metro areas are not entirely prosperous, just as rural areas outside of them are not uniformly distressed. Instead, both urban and rural places can be fast-growing and grapple with poverty among racially and ethnically diverse populations. Thus, rather than confront local restrictions, urban and rural communities benefit from flexibility in approaches to inclusive regional economic revitalization.

State preemption can hurt rural and suburban interests—not just big city ones

When states thwart local control, they undermine rural and suburban actions and interests as well. For example, in 2021, when the state of Montana banned localities from enacting inclusionary zoning, it took away the small city of Bozeman’s primary tool to address a growing affordable housing crisis among local workers—a crisis exacerbated by a pandemic-era influx of new residents into this predominantly rural recreational center.

And similarly in Mississippi, tensions between the state and the city of Jackson—mounting from chronic underinvestment and decades of de jure and de facto segregation—culminated in a systemic water crisis that harmed residents and businesses across several counties, including suburban residents exasperated by leaders’ inability to improve a regional water service.

Culture clashes between states and cities can undermine business goals

States’ passage of divisive social legislation has directly and indirectly complicated some business and civic goals to promote an inclusive economy.

To start, state legislation cracking down on racial equity strategies or climate investments are at odds with public opinion and the business imperative to embrace diversity and environmental responsibility as keys to competitiveness. Polls by Just Capital, a stakeholder capitalism nonprofit, found that the majority of all voters, regardless of political party affiliation, believe it is important for companies and the economy to prioritize workers, advance racial equity, and mitigate environmental harm.[iii] Brookings Metro’s own analyses have provided evidence of the gains to business and regional economies when leaders are more intentional about investing in diverse talent and Black-owned businesses.

For these reasons, some employers and employer groups have found themselves having to oppose state policies that do not advance fairness, equality, and rights. They believe that a welcoming business environment is key to attracting and retaining skilled labor, cultivating diverse entrepreneurs, and being competitive overall in today’s innovative economy. For instance, after Indiana passed a near total abortion ban earlier this year, pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly, which is based there, released a statement saying that the company “will be forced to plan for more employment growth outside our home state.”

Initial evidence shows that such socially conservative legislation has not hurt near-term job prospects in states such as Texas and Florida, which have gained population and new tech businesses in recent years. (Established tech hubs such as San Francisco and San Jose, Calif. have added jobs too, albeit more slowly.) However, the state legislative climate has prompted business groups in growing tech job markets to advocate for racial and social equity and local control, and against anti-diversity or “discriminatory legislation” that could undermine economic development efforts.

Furthermore, state leaders’ culture-war focus has taken up a lot of political attention and capital, distracting from opportunities to effectively engage major employers and regional business groups in bipartisan, cross-sector cooperation on job training, economic development, and other key elements of global competitiveness.

Punitive actions by states can hurt the creative use of federal investments to improve opportunity

Finally, state punitive actions on localities could hinder the creative use of billions of federal dollars now available to build long-term prosperity, modernize infrastructure, and invest in innovation, manufacturing, and green jobs. Some state leaders have already limited the use of this federal funding, potentially foreshadowing what might come:

- Some states have legally challenged the use of race-based criteria in federal programs to redress historic wrongs, thus limiting local efforts to structurally expand economic opportunity. For instance, a Texas state commissioner filed a lawsuit to stop a new federal program to provide debt relief to Black farmers, who have suffered from decades of discriminatory and structural barriers in affording and owning their own land and agricultural assets.

- Some states have withheld or rejected critical federal formula grants to localities if they believed local entities were engaging in activities that run afoul of partisan goals. In Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott withheld portions of two counties’ CARES Act funding because of the way their school districts handled books and curricula. And in Iowa, Gov. Kim Reynolds rejected the state’s allocation of federal funds to schools for COVID-19 testing.

- State punitive actions could create an overall chilling effect on the pursuit of transformative solutions, as an Urban Institute study found. This could result in wasted opportunities to use these rare public sector investments for bold policy experiments that grow jobs and incomes, re-imagine the built environment, and protect urban and rural communities from climate change.

This report is not intended to solve all areas of contention between states and cities. It does not address the structural advantages that redistricting brings to political parties in achieving aims at the state or local level, nor does it offer ways to ensure courts legally protect local determination and home rule. Instead, this report argues that state and local leaders must use their shared interest in the economy and opportunity—as well as this rare opportunity for massive federal place-based investment—to reset their partnership.

We believe that governors, state legislators, and local leaders can prioritize economic and quality-of-life concerns shared by rural and metropolitan residents, such as ensuring all residents can earn a good living, raise their families in safe and affordable neighborhoods, and access clean water, reliable energy, and broadband. Meanwhile, our discussions with mayors and regional business leaders reveal that, for all their frustrations with state dynamics, they have not abandoned a commitment to working constructively with their states—even through deep disagreements—to deliver quality services and transformational initiatives for their constituents, especially improving outcomes for workers, families, and neighborhoods that have been historically overlooked.

The following section offers a few principles by which states and local leaders can improve cooperation and dramatically expand economic growth and opportunity across communities. In return, this cooperation will fortify America’s standing in the world as a global leader in innovation and competitiveness, broad-based opportunity, and a government that works for its people.

States should set high-level goals and reward local and regional innovation

States are managing a high volume of federal funding opportunities from the four signature laws supporting economic recovery, infrastructure, innovation, and climate resilience. One way to make these investments a force multiplier is to engage a cross-section of leaders in cities and regions in setting clear, high-level statewide goals governing state investments, and then reward creative local plans and projects to achieve those goals. In other words, rather than be punitive, states have an opportunity to use available funding as carrots for coalitions of local and regional leaders to close opportunity gaps and develop pioneering, globally relevant projects that make the state truly competitive. Where possible, they can prioritize projects that connect urban, suburban, and exurban/rural assets.

For federal dollars and competitive opportunities that flow directly to local and regional entities, states should grant those entities agency in their decisions, co-invest in solutions through matching state resources, and provide planning and technical assistance so that low-capacity urban and rural communities can make the most of the funding.

States themselves can also establish a framework for innovative solutions that then unleash local solutions. For instance, our Brookings colleague Annelies Goger has documented how states can lead reforms in workforce and education policies that reward non-traditional, non-college-degree students and adults for exhibiting skills and competencies acquired outside of formal learning environments. Such reforms would help regional employers who are urgently seeking workers, as well as local leaders eager to help existing workers find better-paying careers. Alabama, Florida, and Ohio are early innovators to watch.

One example of states rewarding local solutions can be found in Indiana. There, Gov. Eric Holcomb and the state legislature approved the use of $500 million in federal American Rescue Plan Act funds to create a statewide regional challenge grant that provides planning and implementation dollars for each of the state’s metro areas and urban-rural regions to revitalize their economy and commercial corridors. Called the Regional Economic Acceleration and Development Initiative (READI), the grant sets broad goals around talent development, economic opportunity, and quality of life, while emphasizing the importance of achieving regional—not local—outcomes that benefit cities and rural areas.

City leaders can strengthen alliances, including with suburban and exurban leaders, to be a more effective force

While metro areas have notable economic power, they have less political power, especially with state legislatures that have long favored rural interests over urban ones. Metro areas are governed not by formal governments but by networks of leaders that span government, business, nonprofits, universities, and philanthropy. They are also not uniformly “blue” as public headlines often convey, due to the diversity of political viewpoints across the counties that make up a metro area. Thus, to ensure that shared regional economic interests translate to state political support, local leaders should organize statewide and regionally.

For example, some mayors and regional chambers of commerce have joined forces to articulate a common agenda to state leaders. These include the Ohio Mayors Alliance, the bipartisan Texas’ Big City Mayors group, and the Tennessee Metro Chambers coalition.

Within regions, city leaders can also be more intentional in building alliances across cities, suburbs, and rural areas. Doing so would generate win-win solutions for economic prosperity and increase the chances for cross-party, multi-district support in state legislatures and governors’ mansions.

Two of the 21 winners of the $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) grant offer insights into the importance of urban-rural connections and state engagement to regional prosperity. The BBBRC is designed to help regions deepen the competitive advantages of their major industry clusters in ways that expand opportunity for underserved populations and communities. In southwestern Pennsylvania, a coalition anchored in the Pittsburgh area has crafted a comprehensive approach to growing the region’s robotics and autonomous technologies cluster in ways that will lift prospects for women, workers of color, and workers and entrepreneurs in coal-impacted communities, with support from state officials. And in Georgia, a statewide coalition of leaders, organized out of Georgia Tech in Atlanta, has formed partnerships with historically Black colleges and universities as well as rural institutions so that advancements in artificial intelligence in priority clusters will lead to “demographic and geographic justice.” The coalition’s vision and organizing include active leadership and participation from the governor’s office and cabinet.

Governors and state lawmakers can forge multi-jurisdictional, issue-based coalitions—not just political ones

In today’s hyper-partisan climate, Democratic and Republican governors have organized into separate camps, supporting and opposing provisions in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and Inflation Reduction Act as those programs move into implementation. Nationally, such ideological organizing could translate into urban and rural factions within state legislatures. What’s needed are state legislative caucuses organized around issues such as the opportunities federal funding has made available, which can bring together lawmakers that reflect the diverse political, geographic, and sector-based interests in their regions.

In an evergreen 2005 paper about urban and metropolitan coalitions in state legislatures, one type of coalition stands out as particularly effective: governor-brokered coalitions in which “governors (including Republican governors) often play a key role in building cross-party legislative coalitions to support urban priorities.”

As the chief executive in the state, governors often set and design statewide efforts around climate planning, infrastructure, and economic and workforce development strategies. Unlike legislators focused on their districts, governors and their staff travel statewide and have a strong understanding of key needs across the state. Governors also often need legislative support to authorize or finance vital initiatives, and therefore need to build relationships that find common ground between legislators representing big cities and those representing smaller communities.

There are two modern examples of the powerful role governors can play in bringing urban, suburban, and rural legislators together on behalf of communities. The first is in Tennessee: In 2017, Republican Gov. Bill Haslam proposed raising the state gas tax for the first time in nearly 30 years to pay for over $10 billion in deferred projects to rebuild roads, bridges, and other major transportation needs across the state. His proposal included giving permission to local municipalities to go to voters through ballot initiatives to pay for regional transportation priorities, which received endorsement from Nashville’s mayor and regional business chamber. But the Republican-controlled legislature resisted any notion of raising taxes. After enormous work behind the scenes with leaders from both parties and across districts, Gov. Haslam was able to secure a legislative victory and sustained revenue source to deliver on local communities’ desire for new and substantially upgraded transportation projects.

The second example comes from West Virginia. In the November 2022 election, Republican Gov. Jim Justice campaigned against a ballot measure proposed by Republican state legislators that would give the state authority to regulate property taxes, which are counties’ primary revenue source. The intent behind the measure was to enable state legislators to cut property taxes for certain businesses in order to attract economic development. But Gov. Justice argued in favor of local control of such finances. Voters ultimately rejected the measure by a wide margin.

In a recent book, political scientist Jacob M. Grumbach argues that the current fusion of national party politics and federalism is creating “laboratories against democracy,” in which state policy actions are becoming vehicles for advancing national party objectives rather than meeting the needs of their constituents. Indeed, the nation’s extreme partisanship has infected the intergovernmental system. This stands in contrast to the past, when party labels had less of a grip on matters such as supporting teachers, attracting jobs, or providing reliable drinking water. State and local polarization does not need to get worse or be the norm.

With recent federal investments creating an opportunity for the U.S. to embark on a dynamic, inclusive, and climate-resilient future, it’s time for states and cities to reclaim their mantle as laboratories of democracy. Rather than squabble over culture-war issues or score political points through harsh pre-emptions, state leaders ought to embrace local and regional leaders as policy partners, not political adversaries—so that together, they can show that they can still get things done on behalf of people and businesses.

Use the interactive feature below to explore metro area GDP data for every state.

[i] A Brookings analysis found that the regional finalists for the federal Build Back Better Regional Challenge grant—a signature initiative in the American Rescue Plan Act—submitted applications in which 30% of proposed funds would be matched by non-federal resources, such as other local and state governments, philanthropy, and industry partners.

[ii] There are limits to this analysis. For instance, gross domestic product is an imperfect proxy for economic success and well-being. It indicates the size of the proverbial economic “pie,” but not the quality of its growth or the nature of who benefits. This analysis also describes the current size of metro area economies—not their economic performance over time. Readers can find that in Brookings’s annual Metro Monitor, a measure and ranking of inclusive economic growth for the large and midsized metro areas.

[iii] Full disclosure: One of the authors of this report is a board member of Just Capital.