COMPETITION

A truly competitive North America

In this chapter, the role of federal and state governments, academia, research centers, and the private sector in furthering competitiveness in North America is analyzed by means of outlining the challenges and opportunities of the health sector. Increasingly, in the age of the knowledge economy, competitiveness hinges upon creating an environment conducive to maximizing the synapsis among different actors, such as needed in health, but also in other sophisticated sectors. In the end, North America’s competition with other regions of the world is for technological leadership, and success requires the participation of many players.

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) modernized the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) by incorporating areas such as digital trade, state-owned enterprises, labor, and environment, small- and medium firms, competitiveness, anticorruption, good regulatory practices, and a functioning dispute resolution system.

While NAFTA was successful first in manufacturing and then in agriculture—and USMCA will further those gains, with the potential exception of the auto sector in light of the too strict rules of origin and in the context of transition to electric/electronic vehicle—the future economic success of North America will depend on deeper regional integration. This will require not only the effective implementation of the current agreement, a commitment from the three federal governments to adhere to the obligations, and respect for the arbitration rulings, but also the commitment of the larger North American community, including state governments, trade unions, university systems, the private sector, think tanks, and non-governmental organizations.

With most traditional trade barriers (e.g., import duties) eliminated in the region long ago and relatively low most favored nation duties for the rest of the world1, further economic integration will be contingent on the regulatory environment and technological advancement in North America. Economic value creation increasingly depends on the level of complexity of production processes and the number of linkages between each economic sector. This emphasizes interdependence of many economic factors along the value chain: Design and intellectual property, sourcing of top-quality materials at competitive prices worldwide, availability of multiple types of inputs and technologies, branding, logistics, and sales. This applies to many sectors including high-tech, energy, autos and auto parts (electronic, not only electric, and no longer internal combustion), avionics, machine tools, medical devices, molecular biology, and others.

North America is already competitive in many sectors, but the challenge is to deepen competitiveness by improving conditions for innovation that happen in a decentralized fashion.

China’s success stems precisely from its regional competitive environment where the availability of sourcing is very rich. North America is already competitive in many sectors2, but the challenge is to deepen competitiveness by improving conditions for innovation that happen in a decentralized fashion (for political reasons China is moving in the opposite direction), with a regulatory environment conducive to competition of standards and not just convergence, and by exploiting the region’s significant advantages in terms of developing and attracting talent, and having a diversified and potentially cleaner energy matrix and capital markets able to finance long-term endeavors. In a technologically complex world, success hinges upon, in part, the ability to interact with a myriad of economic agents and diverse sources of innovation. Only a flexible, decentralized regulatory environment fosters such conditions. Longer-term richness and flexibility ought to be North America’s main advantages over a centralized and more rigid system such as China’s.

Mexico has the potential to play a significant role in the production processes of most of these sectors, but it would require a significant shift (if not 180 degrees turn) in policy areas related to logistics, energy, research and development, and rule of law. USMCA can be a catalyst for these developments. For example, Mexico could support the regional health sector—one of the largest (and growing) sector in most economies—with the USMCA driving deeper integration and improving competitiveness in this area. Similar arguments could be made for other sectors as well.

The health sector and its role in strengthening competitiveness

Healthcare is not only the largest (and growing) sector in most economies, but also one of the more complex. It involves a long value chain with complicated links that can be capital intensive (when research and development are required). It also entails sophisticated manufacturing and strict quality and sanitary controls, while being labor intensive, particularly mid- and downstream in the provision of healthcare. Most of the time, policy analysts focus on the sector’s costs as it impacts government budgets. However, healthcare is also a significant area for value added creation and jobs for the region.

Traditionally, most trade agreements, including USMCA, are silent in terms of the health sector due to the mostly local nature of its services. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear the interdependence of healthcare across borders, and also the risk of relying only on one or two sourcing countries. For this reason, there is now a conscious effort by policymakers to ensure sourcing diversification in the health sector and leverage its potential for strengthening competitiveness.

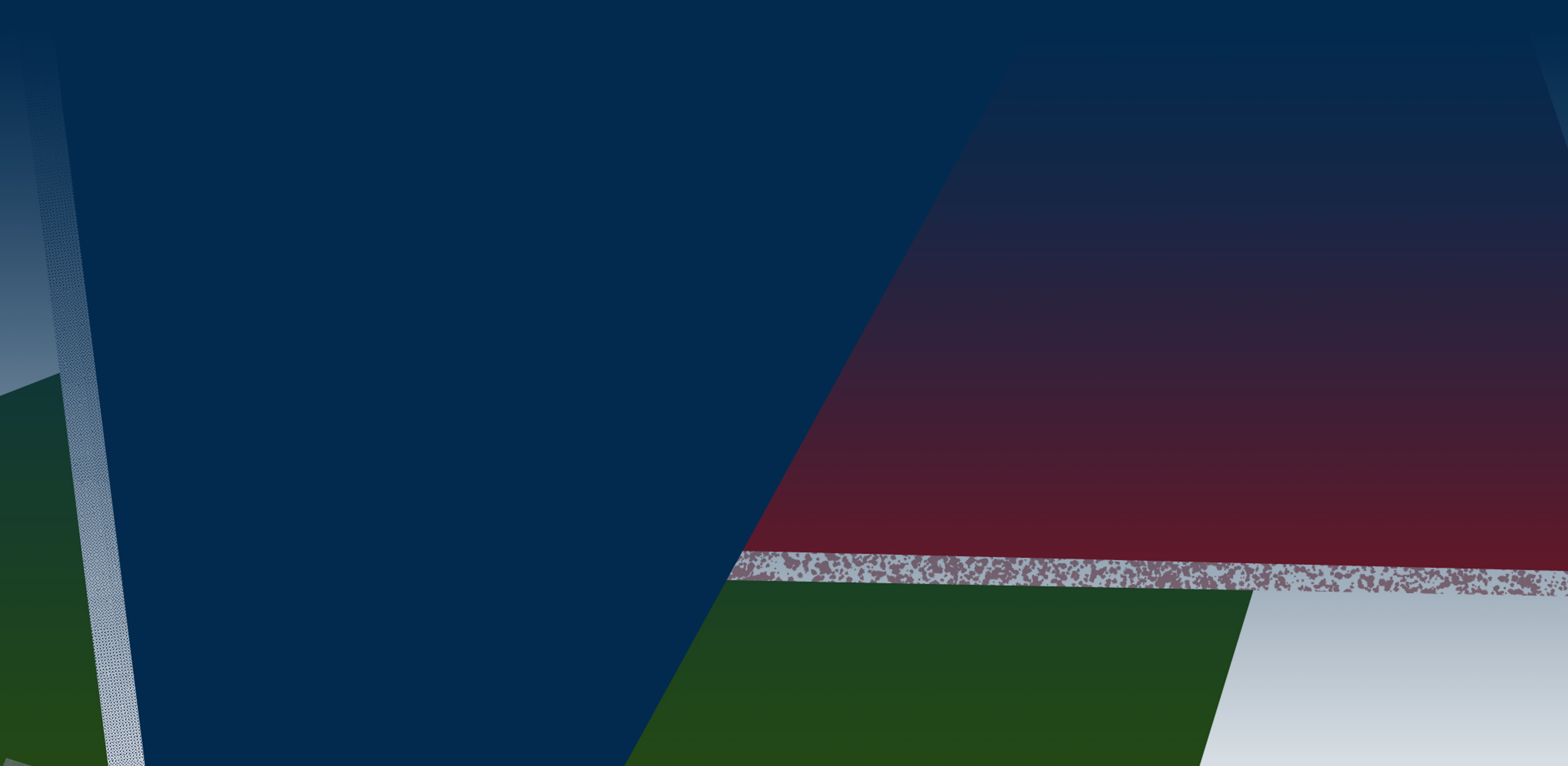

As Graph 4 shows, Mexico is already one of the largest suppliers of medical devices and medication to the U.S. (competing head-to-head with China): Surgical clothing, scalpels, stents, orthopedic gear, dental equipment, and many others. The COVID-19 pandemic has proven Mexico is a reliable supplier of these essential products; nearshoring and diversification of supplier risk mean more production will be done in the region.

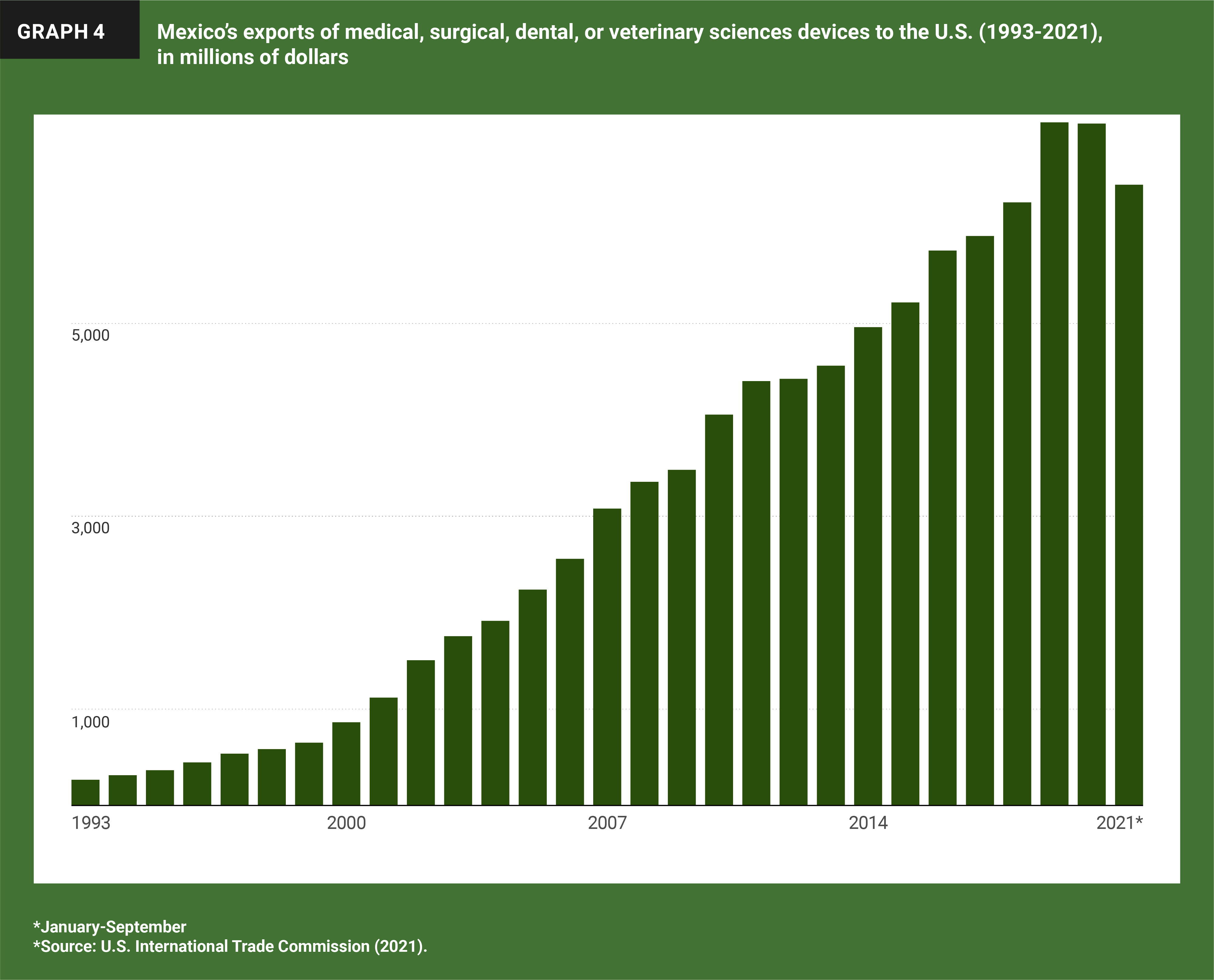

Furthermore, Mexico increased nearly 10 percentage points its market share of these exports to the U.S. between 2001 and September 2021 (from 20 to 28 percent), as the following graphs show:

Graph 5 illustrates Mexico’s potential to continue the upward trend, but to fully benefit, it needs to develop competitive production of key inputs of medical devices, such as specialized steels and aluminum, resins and plastics, and glass and fiber glass (all these are natural gas intensive and North America is the most competitive region in the world for this essential input), and increase investment in research and development (R&D). Medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and molecular biology are similar to advanced manufacturing in that they thrive in an environment that promotes innovation through applied R&D and where multiple linkages between industrial and services sectors are present. Moreover, this is consistent with the aim to strengthen supply chains in North America and the promotion of nearshoring to diversify exposure to Chinese risk.3

Proper implementation of USMCA can provide the framework that allows the regional integration to deepen and support the health sector’s success. Participation of multiple actors will play an important part: Federal governments (as regulators and resource providers) but also state governments (as healthcare providers in hospitals, promoters of investment, catalysts for regulatory compliance, source of talent through universities and community colleges), private sector investment, research centers, and think tanks. In this manner, deepening North American integration in the larger health sector depends on the participation of many decentralized actors, while USMCA serves as a framework that allows the integration to deepen. The same would apply to other sectors (including agriculture and food) as well.

Good regulatory practices are important parts of the sector’s success in the region. Chapter 28 of USMCA provides disciplines for consultation and regulatory review, information quality, early planning, plain language use, transparency in the development of regulations, advisory expert groups, regulatory impact assessment, and compatibility and cooperation. While these rules for a proper regulatory framework are important, promoting compliance at the firm level, particularly for small- and medium-size firms, can be useful. Otherwise, significant obstacles, in terms of accessing high quality inputs and ensuring best manufacturing practices, regulatory applications, insurance protection, and others can become insurmountable.

It is in this realm that state governments can assist local manufacturers in obtaining necessary certifications, particularly cross border ones. For example, pharmaceuticals from the state of Jalisco, where many such companies are established, could be supported by the state regulatory compliance promotion office. It could help with obtaining certification from COFEPRIS, a department within the Mexican Secretariat of Health responsible for the importation of medical devices and relevant permits or, even better, from the Federal Drug Administration (FDA).

Furthermore, state authorities could help fund the establishment of laboratories to test for human, animal, and plant sanitary compliance. The lack of testing laboratory capacity can often be a barrier to participating in international trade.

On the pharmaceutical front, moving from manufacturing to the development of innovative medication means a long-term and significant commitment to research. A good place to start is to set up a joint scheme with the three USMCA members so that state healthcare systems can more fully participate in phases two and three of clinical trials. For this, partnering with networks of state hospitals is key. COVID-19 has made it clear that the institutional capacity to carry out phases two and three in clinical trials is necessary to participate in the most profitable links of the health sector value chain. A conscientious effort by state governments can make the difference so that investing in adequate institutional capacity happens.

It is in the downstream that the larger positive impact on jobs can be obtained and where Mexico can derive significant benefits. Patient care is, by its nature, labor intensive and requires a qualified labor force. The U.S. and Canada have a critical shortage of doctors, nurses, and health assistants for hospitals, clinics, retirement homes, and home care services. USMCA provides the necessary framework to mutually recognize professional degrees and issue temporary entry visas for cross-border service provision. The issuance of professional temporary entry visas under the NAFTA and now USMCA (so called TN in the U.S.) has been more successful than most realize.4 According to the Report from the Visa Office5, in 2015 there were 13,093 NAFTA TN visas issued. By 2019, that number had escalated to 21,193 (38.2 percent more). Although COVID-19 diminished the numbers by 2021, the trend will undoubtedly continue.

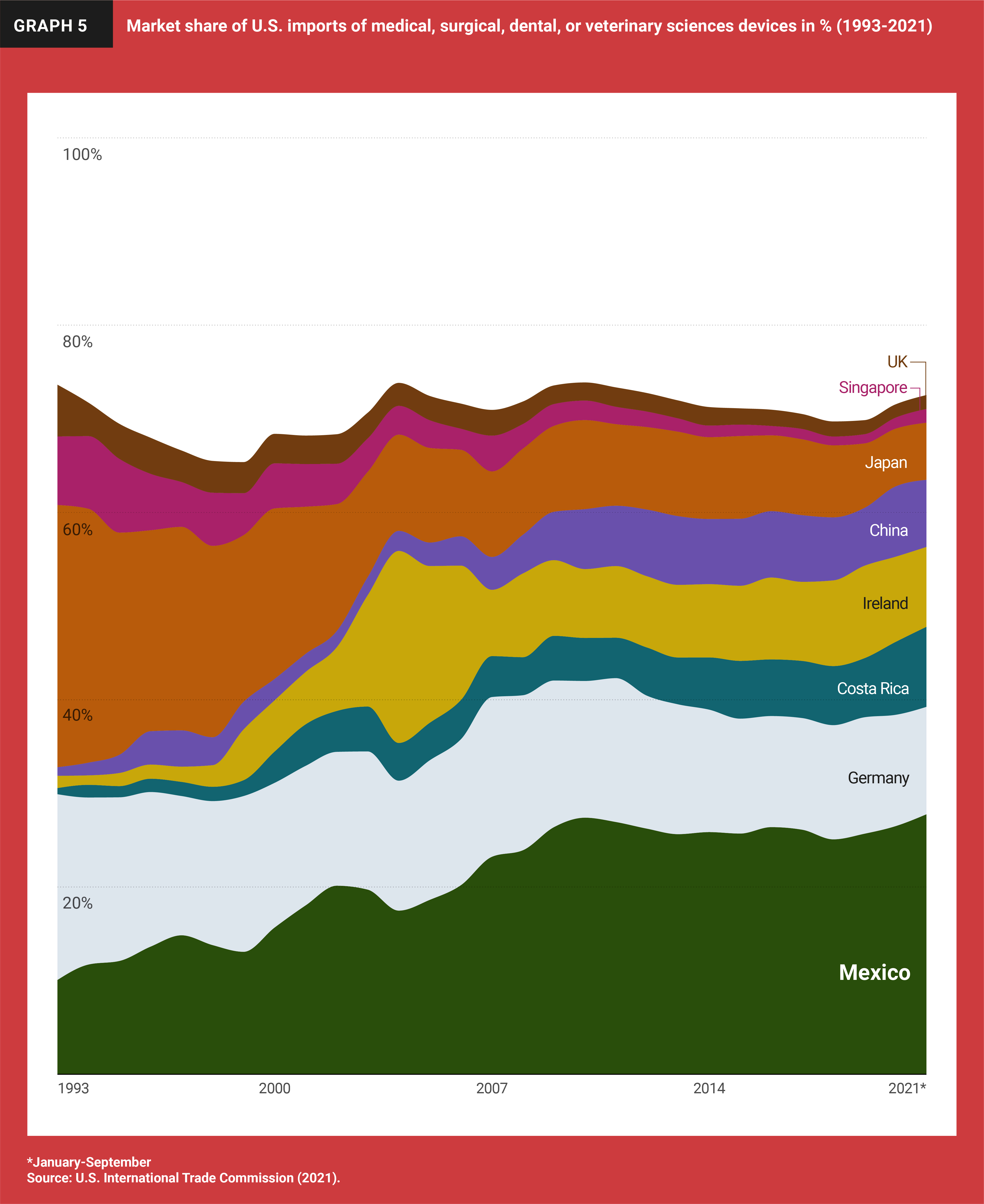

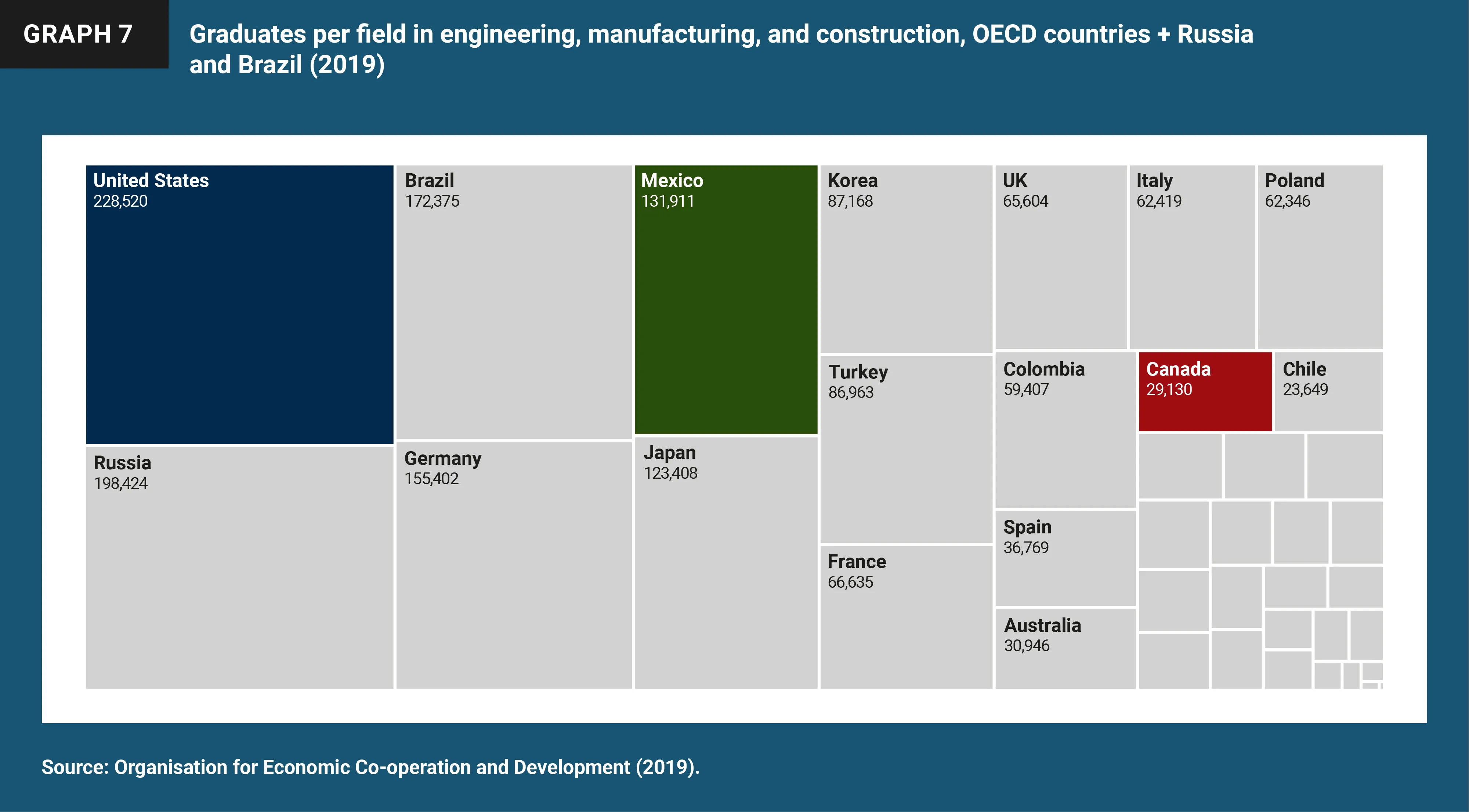

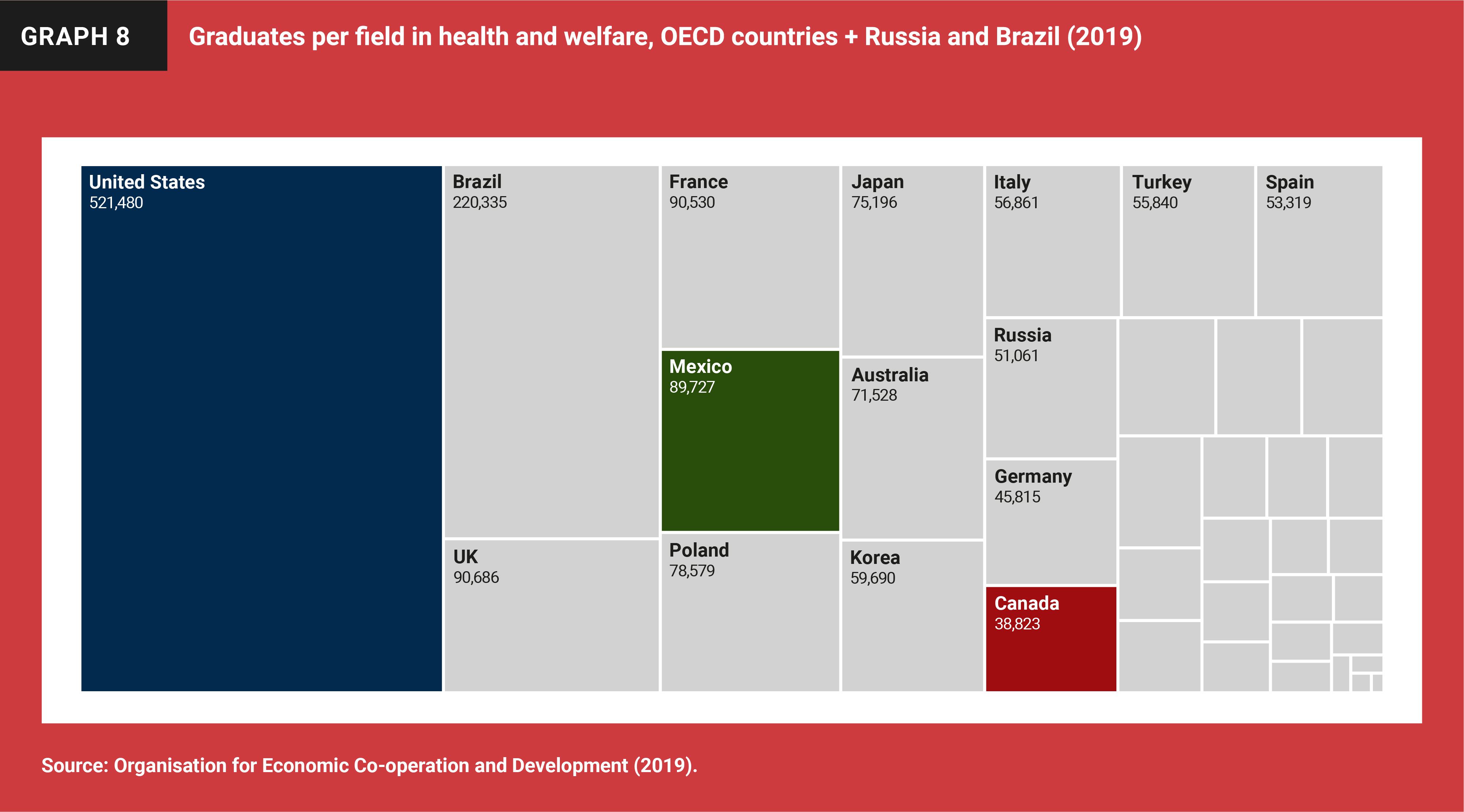

Mexico is already graduating many skilled professionals compared to other countries. The following two graphs show the absolute number of graduates in natural sciences, mathematics, and statistics, as well as engineering, manufacturing, and construction. In natural sciences and mathematics, Mexico has significant room to grow (Graph 6), while it leads (Graph 7) in engineering, manufacturing, and construction (not surprisingly, given NAFTA).

For the health sector, the number of Mexican graduates is also already significant, but insufficient for the expansion that can be envisioned, as shown in Graph 8. Mexico’s healthcare workforce should aim to reach at least the levels of Brazil in the next five years.

However, to really take advantage of the opportunities from more integration and use of talent in healthcare, much more needs to be done, especially at the state level. The principal constraint is on the supply side. Mexico has the young cohorts that could potentially participate, but they lack the proper training and certification to do so. A concerted effort to enroll healthcare students (especially nurses) in professional training courses, to make sure they become proficient in English and partner with key counterparts in the U.S. and Canada, are essential. The role of state governments is crucial in terms of strengthening career training for nurses in universities, as well as technical and vocational schools, for other health-related trades. Some state governments in Mexico could undertake this effort, while California, Texas, and other U.S. states could participate with large student exchange programs. The resulting “bilateral” students could be more easily certified to work in both countries.

There is a strong demand for these types of experience and training, so that qualified candidates can be binationally certified and more easily find jobs or obtain visas. On the visa front, an important improvement may be to issue multiple and not only temporary entry visas so that healthcare personnel can spend part of the year overseas and the rest back home.

Some in Mexico may object to the idea of “exporting” health sector talent to the U.S. and Canada; they may fear the country may lose nurses and other health professionals who are not easy to replace. The concern is even more acute in the absence of an ambitious program to significantly increase their numbers. The fear, however, is unfounded. The number of health professionals is not fixed. Moreover, a constant stream of trained personnel would generate significant revenues as compensation in the sector is higher than average wages and much higher than wages in manufacturing in the country.

Furthermore, the expansion of health training and facilities could support the growth of medical tourism, so that a growing number of patients are treated in the country. Mexico has significant comparative advantage for medical tourism, for both short- and long-term care: A young trainable labor force, year-round welcoming weather, a large network of airports (more than 30) that serve directly from the U.S., same time zones, and well-known hospitality service. Medical tourism in Mexico is already happening: Deambulatory in border towns such as Tijuana and Juarez, that serve patients from California and Texas, and hospitalization in Mexico City, Monterrey, Guadalajara, and Leon.

For future growth, the opportunity lies on developing adequate urban planning, environmentally sustainable water and water treatment, universities with qualified healthcare programs, and hospitals specializing in relevant branches of medicine. Fonatur, the Mexican agency responsible for developing a number of tourism destinations, including Cancún, Ixtapa, and Nuevo Vallarta, could be in charge of selecting the sites for this purpose. Fonatur has experience designing attractive and sustainable destinations and could develop clusters of hospitals, universities, hotels, and entertainment facilities, as well as residential areas for healthcare and hospitality personnel. These clusters could become an important attraction for not only patients from North America (including Mexico) and other countries, but for talent and jobs. In terms of suitable locations, Fonatur has land already reserved south of Mazatlán, and locations near Acapulco and the San Pedro development next to Tecate at the border with California could be suitable. Digital technology can also play a role through remote surgery, connected medical devices, and electronic patient files.

In the past, insurance coverage and Medicare reimbursement were seen as prerequisites for securing investments in medical tourism, making it difficult for this industry to thrive in Mexico. A better approach may be to illustrate the industry’s potential for providing high quality healthcare services at competitive prices, to then become attractive for insurers. The growing community of U.S. nationals—currently at two million and considered the largest in the world—that reside almost permanently in Mexico could become a large market for this industry.

A fully integrated and competitive healthcare industry in Mexico would allow it to compete in an industry where innovation and technology play such significant roles. USMCA membership offers Mexico a comparative advantage in this area, but it is insufficient. Realizing its full potential requires complementary efforts by many actors: Federal and state governments, regulators, universities, think tanks, NGOs, and private sector investment. Deepening integration in other complex sectors need an integrated vision as well.

Endnotes

- 1. Compared to most other trade agreements, Article 303 of NAFTA and USMCA limits drawback and duty remission programs to incentivize use of regional components; a consequence of this article is to encourage lowering of MFN duties on intermediate goods.

- 2. According to U.S. Census figures several sectors have experienced significant value-added growth during 2009-2019 in the U.S., such as motor vehicles bodies and trailers, magnetic and optical media, industrial machinery, household appliances, electrical equipment and components, ships and boats, while Mexico and Canada are clearly competitive in the US as they are its second and third largest suppliers.

- 3. The White House, February 24, 2021, Executive Order on America’s Supply Chains. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/02/24/executive-order-on-americas-supply-chains/ See also The White House, June 2021, Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-based Growth. 100-day Reviews under Executive Order 14017. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/100-day-supply-chain-review-report.pdf.

- 4. See, for instance, “Legal Migration and Free Trade in the NAFTA Era: Beyond Migration Rhetoric”, by Miguel Ángel Jiménez, Mexico Institute Wilson Center and Comexi. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/legal-migration-and-free-trade-the-nafta-era-beyond-migration-rhetoric

- 5. VISA OFFICE Nonimmigrant visas issued by classification (including border crossing cards) 2019 Report, US. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairshttps://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/AnnualReports/FY2019AnnualReport/FY19AnnualReport-TableXVI-B.pdf

References

DE LA CALLE, Luis How North American trade can restore balance with China The Hill May14 2021

DE LA CALLE, Luis Respecting other people´s rights as a comparative advantage: a private sector angle in The Missing Reform: strengthening rule of law in Mexico (Ríos and Wood, editors) Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, p.110, 2016

JIMÉNEZ, Miguel Ángel Legal Migration and Free Trade in the NAFTA Era: Beyond Migration Rhetoric Mexico Institute Wilson Center and Comexi

Available at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/legal-migration-and-free-trade-the-nafta-era-beyond-migration-rhetoric

OECD. STAT. Education at a Glance, Share of graduates by field

Available at: https://stats.oecd.org/

VISA OFFICE Nonimmigrant visas issued by classification (including border crossing cards) 2019 Report, US. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs

https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/AnnualReports/FY2019AnnualReport/FY19AnnualReport-TableXVI-A.pdf

Viewpoints

Lance Fritz, Juan Gallardo Thurlow, and Victor Dodig underscore the business community’s view on the benefits of the USMCA and the work that remains to be done.